Reading through the back-issues of the Tolkien Society members-journal Amon Hen, in #272 I came across a report of a conference in Italy titled “Tolkien and the literature of the Fourth Age”, which took place just before Christmas 2017. Some big names were there, including Tom Shippey and Thomas Honegger. The latter presented “Tolkien and Lovecraft”, and the report summarised some of the talk’s main points…

– both worked within frameworks of myth and to an extent dream;

– both were interested in changes in language over large time-scales;

– both were interested in “worlds in decay” which nevertheless contain decaying “monuments of fallen grandeur”;

– both loved the mystery of ancient things, ancient landscapes;

– Tolkien’s late “Smith of Wootton Major” tale as comparable to Lovecraft “The Silver Key” and parts of “Dream-Quest”;

– both wrote foundational “theoretical texts” which shaped the work of those who came after them (“On Fairy Stories”, and “Supernatural Literature”).

– both inspired many imitators, continuators, borrowers, and also a wealth of illustrators;

– August Derleth as being in a somewhat similar situation as Christopher Tolkien, as ‘posthumous editor’ and ‘re-shaper’.

To which I would add…

– both gave ‘creative house-room’ to notions of a sort of personal racial memory, and past lives;

– both were interested in time-travel, as the idea then stood;

– both had a very rich store of knowledge about the classical world / the wild North;

– both wrote tales set within the framing of ‘recovered but partial’ scholarly knowledge (often by amateurs);

– both were anti-Freud and his acolytes, and more generally anti-modernist;

– both went ‘over the heads’ of the literary establishment, and appealed direct to the masses;

– both used a literary technique and style deemed ‘outmoded’ for the era;

– the depiction of evil was a key focus for both authors;

– both were aware of the power of ‘un-named creatures’ to evoke fear (though Tolkien uses these with a very light touch);

– both had ‘broadcast telepathy’ by the evil one, e.g. in Tolkien the evil Sauron mentally sends out his Cthulhu-like ‘call’ to all evil things;

– both greatly valued poetry and the oral tradition;

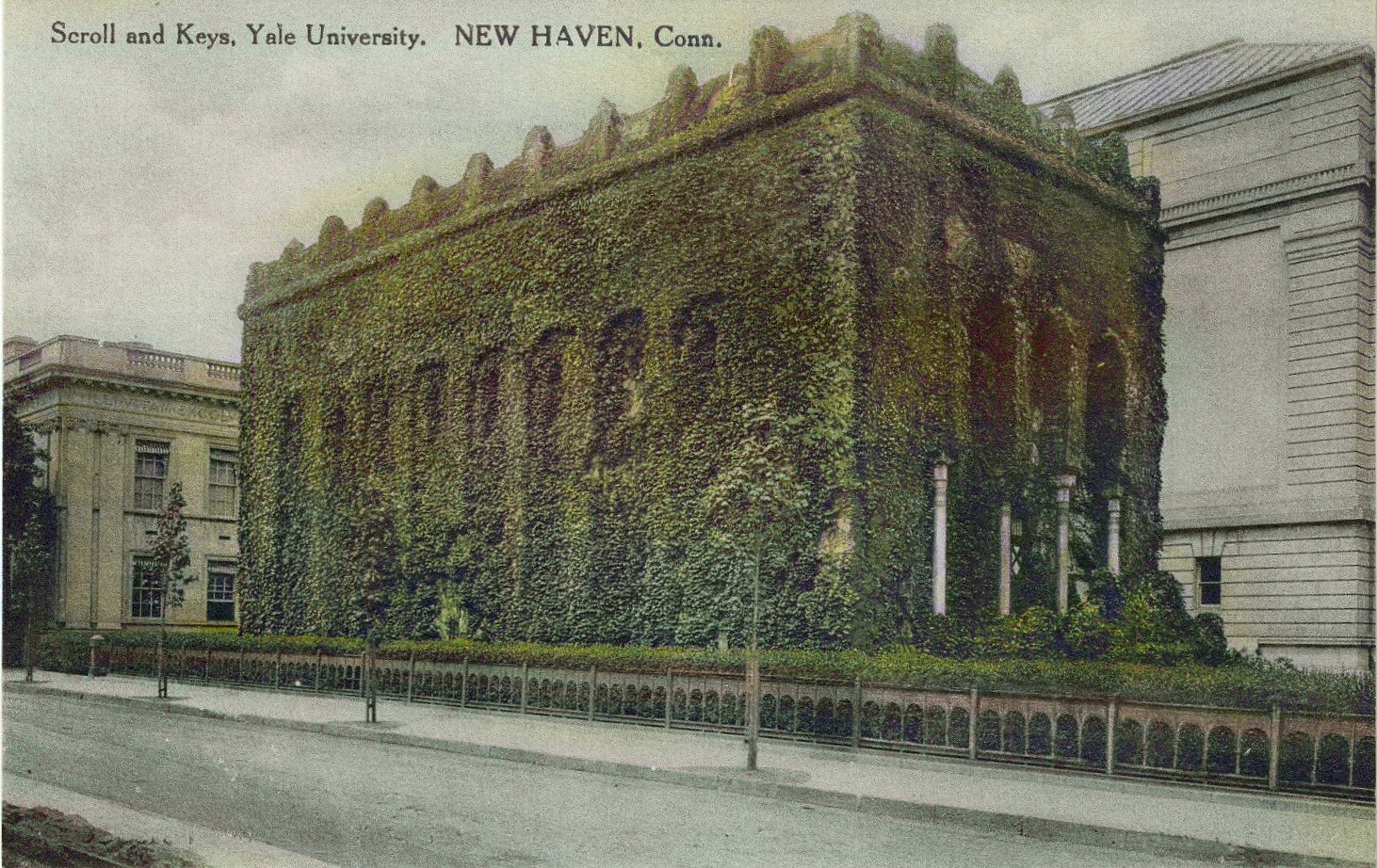

– both were deeply English in outlook and heritage, although Lovecraft was ‘at one remove’ in New England;

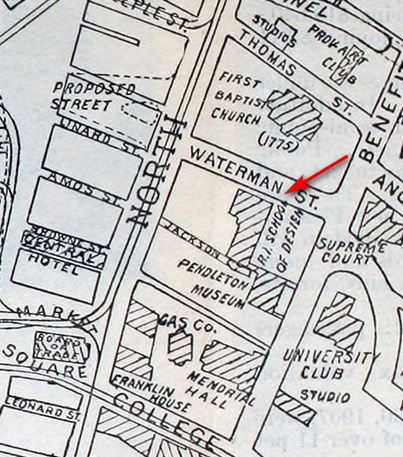

– they both deeply valued the physical fabric/landscape and traditions and people of their ‘local place’, for Lovecraft New England and 18th-century England, and for Tolkien mediaeval ‘old England’ and its later survivals.

– both were keen genealogists, though Tolkien’s family-trees were fictional.

– both were keen walkers, in different ways (‘dawdling vs. darting’ might sum it up), though both had a keen eye for traces of the past of a place;

– neither was afraid to offer readers long loving descriptions of a landscape in its season, adding strong doses of ‘travel writing’ to their fiction;

– both valued the imagery of the sea and the coast, in a romantic way;

– both were keen to correctly depict astronomical observations in their fiction;

– both were fatherless and were raised by kindly men who nurtured their talents;

– both were very open to collaborating with and mentoring / working equally with intelligent women;

– both greatly valued the simple Epicurean consolations of life in their personal everyday, though each in their different ways;

– both had a robust and deep-rooted conservative outlook, and could draw (if needed) on robust intellectual support for that outlook;

– neither man expected his tales would make him world-famous for centuries to come, with not only wide public readership but also many attentive scholars and historians.

– many trenchant early critics claimed to have read their writing(s), but quite evidently had not done so (or, at best, as Tom Shippey says… “had not read them with any attention”). At the same time, both were often reviled as arch conservatives.

– the work of both men inspired a wealth of popular music after their deaths, first in various forms of heavy-metal music and now more widely.

‘Were the 2017 proceedings published?’ I wondered. I tracked them down to the first issue of the Italian journal I Quaderni di Arda (2020). Sadly the papers given in English are there translated, and the Lovecraft talk becomes “Re-incantare un mondo dis-incantato: Tolkien e Lovecraft (1890-1937)”.

I see the English PDF used to be on the journal’s iquadernidiarda.it website, but that domain and site have now lapsed. Then I found that the English paper had since been deposited as “Re-enchanting a Dis-enchanted World: Tolkien (1892-1973) and Lovecraft (1890-1937)”. For non Academia.edu members, this can be had by searching for “Re-enchanting a Dis-enchanted World” on Google Scholar. Scholar has an arrangement with Academia.edu for many (but not all) papers re: easy no-membership downloads.

Were there any points in the PDF to add to the list given by the conference report? Just a few…

– both often suggested an “indissoluble connection between language and identity”;

– both “subscribe to the general principle of phonaesthetics”, for example with evil speech sounding ugly and jarring;

– neither was afraid to use dialect on the page.

Honegger published on Lovecraft in English a little later, in the journal Fastitocalon #9, 1 & 2: ‘Fantastic Languages / The Language of the Fantastic (2020). This had his essay “Language, Historical Depth, and the Fantastic in the Work of H.P. Lovecraft”.

Both journal volumes are still available, in paper, for now.

And finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t also note the new book in Italian, Tolkien e Lovecraft (2023). This is now at least on Amazon.co.uk and can be added to a personal List, but cannot be shipped to the UK. I can’t read Italian and haven’t seen it, nor any review for it.