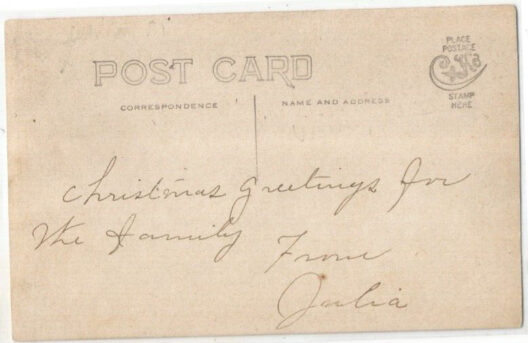

I had little hope of ever finding a picture of Julia A. Maxfield’s ice-cream parlour, which was something of a repeating rural venue for the Lovecraft circle. But one has popped up at last. I’ve here colourised it. The card is still available, for a hefty price, on eBay.

Saturday morning all three of us went to Colonial Warren — down the east shore of the bay — and staged an ice-cream eating contest at the celebrated emporium of Mrs. Julia A. Maxfield — an aged matron of antient Warren lineage who has won fame by serving more flavours of ice cream than any other purveyor either living or dead. There are twenty-eight varieties this season, and we sampled them all within the course of an hour.

The game was, in the course of one hour…

Each would order a double portion — two kinds — and by dividing equally would ensure six flavours each round. Five rounds took us all through the twenty-eight and two to carry. Mortonius [Morton] and I each consumed two and one-half quarts, but Wandrei fell down toward the last. Now James Ferdinand and I will have to stage an elimination match to determine the champion!”

There were a number of visits and other contests…

Another time we visited the colonial seaport of Warren, down the East shore of the bay — incidentally stopping at a place (quite a rendezvous of our gang) where 28 varieties of ice cream are sold. We had six varieties apiece — my choices being grape, chocolate chip, macaroon, cherry, banana, and orange-pineapple.

Then back home via […] ancient Warren […] at which latter place we paused at the famous Maxfield’s (a rendezvous of Morton, Cook, & other visitors of mine) for a dinner consisting entirely of ice cream – a pint & a half each. HPL: chocolate, coffee, caramel, banana, lemon, strawberry.

After digesting Warren’s quiet lanes and doorways we went across the tracks to Aunt Julia’s, where we tanked up on twelve different kinds of ice cream — all they’re serving at this time of year [March]. The antient gentle-woman, of course, was not there – since (as I wish to gawd I could) she spends all her winters in Florida — but the bimbo in charge was very pleasant, and we got quick service since we were the only customers.

American Biography (1924) confirms the at-or-near 71 Federal Street location. At Warren…

is where ‘Elmhurst’, famous for Mrs. Maxfield’s ice cream, is located on Federal Street.

However the 1932 Providence Directory has it on Narragansett Av. There were likely several different ways of approaching it. Today Federal Street looks like a fine place, but seems too short in terms of numbering. Perhaps it once ran on, and would thus have given us a No. 71? Narragansett Av. also seems gone, but one wonders if it once ran along the shoreline and Federal Street ran on to meet it? But it would probably take a local sleuth to pinpoint the location and say if the building survives.

As for Lovecraft’s ice cream craving, it began early, if the evidence of its use in his seminal poetry is anything to go by. In his early comic/cosmic poem “The Poe-et’s Nightmare” (1916)…

Each eve he sought his bashful Muse to wake

With overdoses of ice cream and cake

The 1925 telegraphic diary has plentiful of mentions of ice cream in New York City.

By 1934 ice cream has become something of a staple meal on his travels south. June 1934, in Charleston…

Still on 20¢ a day for food, but off the canned stuff. Morning — 5¢ cup of ice cream. Evening, 10¢ bowl of Mexican chili and another 5¢ cup of ice cream.” […] I “frequently make a full meal of it (and nothing else) in summer.

December 1936. Ice-cream now a costly luxury, as poverty deepened. But still…

Occasionally, of course, extravagant additions [to one’s meagre diet] occur — such as […] a chocolate bar or ice cream at an odd hour [… and yet] the old man still lives — in a fairly hale & hearty state, at that! Oddly enough, I was a semi-invalid in the old days when I didn’t economise. Porridge? Not for Grandpa!

His ice cream cravings were such that in “The Exiles”, a Ray Bradbury ‘Mars’ story after Lovecraft’s death, Bradbury portrays the Martian Lovecraft as an ice cream-aholic…

Lovecraft hurried to a small icebox which somehow survived this red furnace and brought forth two quarts of ice-cream. Emptying these into a large dish he hurried back to his table and began alternately tasting the vanilla ice and scurrying his pen over crisp sheets of writing paper. As the ice-cream melted upon his tongue, a look of almost dreamful exultancy dissolved his face; then he sent his pen dashing. “Sorry. Really, I am awfully busy, gentlemen, Mr. Poe, Mr. Bierce. I have so many letters to write.” […] The writing man tried another delicate spoonful of the cold treasure. There were six empty vanilla ice-cream boxes piled neatly on the hearth from this day’s feasting. And the ice-box, in the quick flash they had seen of its interior, contained a good dozen quarts more.