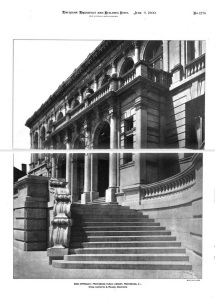

Providence Public Library, as Lovecraft would have known it…

From The American Architect and Building News, 9th June 1900:

Providence Public Library, complete interior floor plans, 1900 (PDF link). May not display properly in Firefox, but is fine in a normal PDF viewer. Best resolution yet found: at 400% one can just about read the lettered titles for each room).

Postcard via the Providence Public Library website, indicating the colour of the entrance stonework.

Postcard via the Providence Public Library website, indicating the colour of the entrance stonework.

* From The American Architect and Building News, 15th September 1900 (pictures were included in International Edition only, not in U.S. edition):

Rear views of the Providence Public Library, 1900.

Rear views of the Providence Public Library, 1900.

For more historical pictures, see the Collection of Providence Public Library.

H. P. Lovecraft and the Providence Public Library

The Providence Public Library membership card records do not appear to have survived from the pre-1914 period, nor the postal mailing list for the monthly bulletin of new books. Yet it seems highly likely that the 9½ year-old H.P. Lovecraft would have joined the new Library as a child member before the grand opening in March 1900. He was probably already a member of the old library, but not to have had him join the new one might have been deemed a very snobbish social misstep on the part of his grandfather and family.

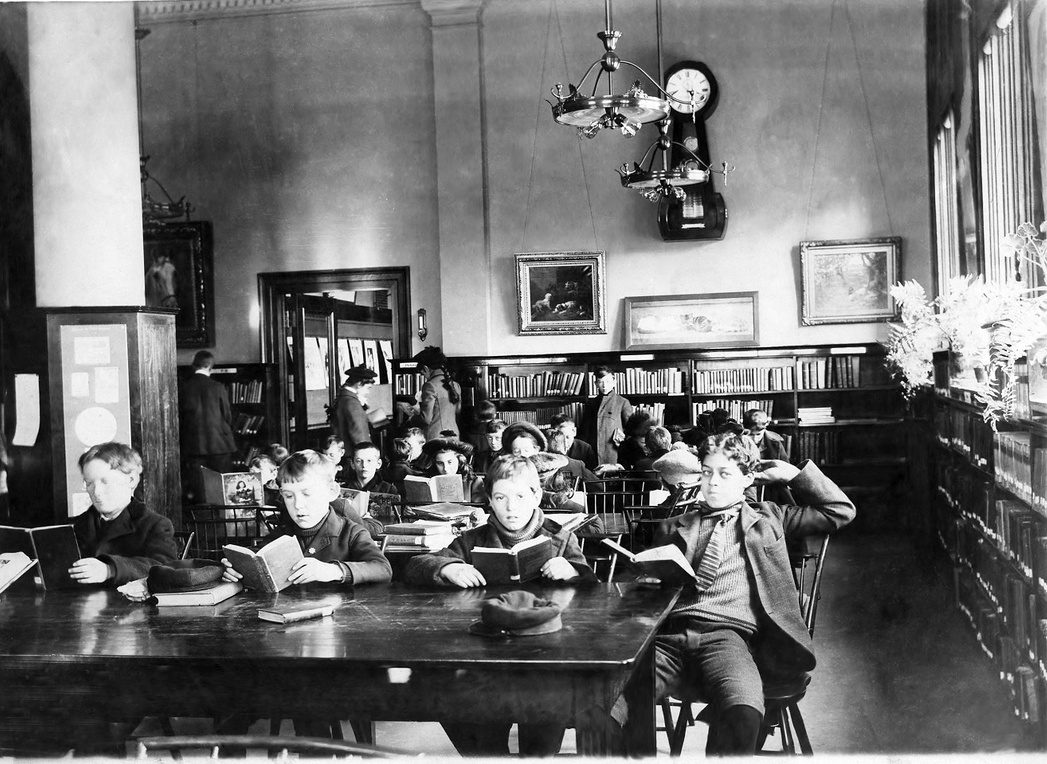

Based on this March 1900 photo and my research on it, my hunch is that Lovecraft (who seems to be third from the left) could have been a founder member of the Library League at the Children’s Library, helping to set the standards of behaviour — as would befit a bookish lad who was the grandson of one of the city’s most successful entrepreneurs and investors.

Picture: Providence Public Library, March 1900. Photo by A. L. Bodwell, the picture taken to document the newly opened new Children’s Library and one of a series to be sent to the Paris World’s Fair. Picture is from the Collection of Providence Public Library.

Picture: Providence Public Library, March 1900. Photo by A. L. Bodwell, the picture taken to document the newly opened new Children’s Library and one of a series to be sent to the Paris World’s Fair. Picture is from the Collection of Providence Public Library.

Lovecraft did not attend school between 1899 and September 1902, and he seems to recall that he had sparse contact at that time with other children. At home he had several substantial and fine home libraries at his disposal. But the new Public Library would have had its enticements, as it evidently also provided exhibitions, summer trips and and lectures for its child Library League members, and so he might have visited when his variable health allowed. A particular enticement might have been the Library’s very large number of current periodicals, unavailable at home. Even from a young age, Lovecraft was always avid for magazines and newspapers. The library took, among many others: Inland Printer; National Geographic; Photo Era; Popular Science; Printing Art; New England Magazine; Punch; Saint Nicholas (popular quality children’s magazine); American Boy (popular boy’s magazine); Typographical Journal; and a handful of railroad magazines. Lovecraft was at this time also an avid fan of various popular adventure and detective fiction books that he probably could not find in his home libraries.

Lovecraft may have started using the adult sections from about age 12, August 1902, if not before. The Children’s Library section had evidently become extremely over-used by 1902, with the Annual Report suggesting some schools had informally offloaded their library responsibilities onto it. This overcrowding may have pushed Lovecraft into the adult sections, something seemingly permitted and even encouraged by the library, even if he had not already made the move. Possibly he was sometimes taken to the Library by his unmemorable private tutors, whom he seems to have suffered occasionally during 1903 and to March 1904.

But I would hazard an educated guess that it was probably from the early summer of 1904 that Lovecraft really began to properly use the adult sections of the Public Library. He was then aged nearly 14, and family calamity had recently and traumatically forced him to move to what he called a “skimpy flat” with his mother. I imagine it was quite pleasant to him to escape to the calm environs of the adult sections of the public library, rather than be shut up with his stifling mother, especially during the winter of 1904/05.

We then skip two years to find the earliest written documentation linking Lovecraft with the Providence Public Library: we have a letter from Lovecraft describing how he became very fond of a Cataloguing Room Messenger boy of his own age, Arthur J. Fredlund. Fredlund is listed as such in the Library’s 1905 Annual Report. Lovecraft later recalled the details for his friend Galpin…

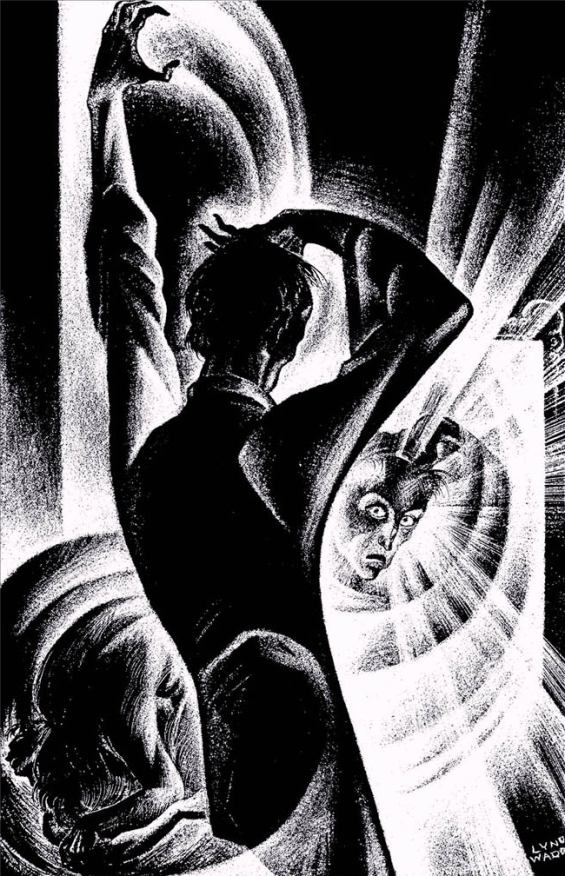

I came across a superficially bright Swedish boy in the Public Library. He worked in the “stack” [Library storeroom for books] where the books were kept and invited him to the house to broaden his mentality (I was fifteen and he was about the same, though he was smaller and seemed younger.) I thought I had uncovered a mute inglorious Milton (he professed a great interest in my work), and despite maternal protest entertained him frequently in my library. I believed in equality then, and reproved him when he called my mother “Ma’am”. I said that a future scientist should not talk like a servant! But ere long he uncovered qualities which did not appeal to me, and I was forced to abandon him to his plebeian fate. I think the experience educated me more than it educated him — I have been more of a cynick since that time! He left the library (by request) and I never saw him more….” (21st August 1918, Letter to Alfred Galpin, Selected Letters I, p.70)

“I was fifteen” dates the start of this friendship to between August 1905 and July 1906, and strongly suggests Lovecraft was a card-carrying member of the Library at that time, and possibly even one who also had a card allowing him access to the “stacks”. The phrase “mute inglorious Milton” is from Gray’s famous poem “Elegy written in a Country Churchyard”, and the meaning is ‘an unregarded peasant genius’. So, by “mute” Lovecraft does not imply that Fredlund rarely spoke.

Lovecraft recalled in a letter that he had suffered a “nervous breakdown (winter ’05-’06)” (Lord of a Visible World, p.32), which must narrow the dates for the Fredlund friendship to Spring 1906 — Autumn 1906, since…

In the September 1906 issue of the Rhode Island Journal HPL [Lovecraft] states that his boyhood friend Arthur Fredlund had taken over as editor of the [his own] Scientific Gazette” (An H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia, p.232)

Fredlund produced no issues under Lovecraft’s guidance, and his name does not appear in the staff lists of the Library’s 1906 Annual Report. The nature of his damning “uncovered qualities” are unknown.

It appears that Lovecraft was still using the Public Library during the early 1910s, and was delving deep into the periodical archives. Citing a Lovecraft letter to Robert Bloch, S.T. Joshi places at circa 1911-13 the date at which Lovecraft…

…read the entire run of the Providence Gazette and Country-Journal (1762-1825) at the Providence Public Library” (S.T. Joshi, I Am Providence, p.135)

Within those dates Lovecraft also evidenced — to a R.I Senator, no less — a startlingly comprehensive knowledge of current political and legislative manoeuvrings, suggesting he was then a frequent visitor to the Library’s periodicals room.

In the absence of Library borrower membership records, the earliest surviving actual official text linking Lovecraft to the Public Library is a record in the 1915 Annual Report, in which the 24 or 25 year-old Lovecraft is noted as having that year donated three “numbers” to the library stock. Presumably these “numbers” were magazines or journal issues.

At some point he presumably discovered and comprehended the Library’s Alfred M. Williams Collection of Folk Lore, standing at a massive 1,909 volumes when catalogued in 1902, and very strong in Irish folklore. The name strikes me as being somewhat similar to Lovecraft’s fictional “Albert N. Wilmarth”, professor of literature and folk lore at Miskatonic University.

In a letter of August 1916 to Kleiner, Lovecraft states…

I intend to spend considerable time at the library searching out the various expressions and conventional proper names used by the classicists, both ancient and English.

Writing to Fritz Leiber about Shakespeare, Lovecraft remarks that he once read one of the bard’s plays…

in an early collection of the sort belonging to the public library.

When Lovecraft first discovered Lord Dunsany he wrote, in a December 1919 letter to Kleiner (Lord of a Visible World, p.71), that…

I have filed recommendations for all his works at the local publick library, and have met with favourable responses.

In a letter to Galpin of April 1920, Lovecraft notes… “I now have from the library both “What is Man?” and “The Mysterious Stranger” [both Mark Twain]”. Also in 1920, to Kleiner in September, he writes…

Saturday I went out for the first time since my journey, visiting the library & picking up an addition to mine own library at a bookstall on the way home. My new possession is entitled “Men & Manners of the Eighteenth Century,” & is by one Susan Hale — who seems to me to have more of industry than of genius.

Doubtless there are more examples of his mentioning the local library in the early letters, but I only have limited access to the letters.

In a letter of the mid 1920s Lovecraft revealed that he carried not only a regular Public Library card, but also a further card that would allow him to access the “stack”, meaning the books storeroom. He was then also well known to the head librarian… “good old William E. Foster”, who had steered the new Library through from its inception in 1900 and who was then still five years from retirement.