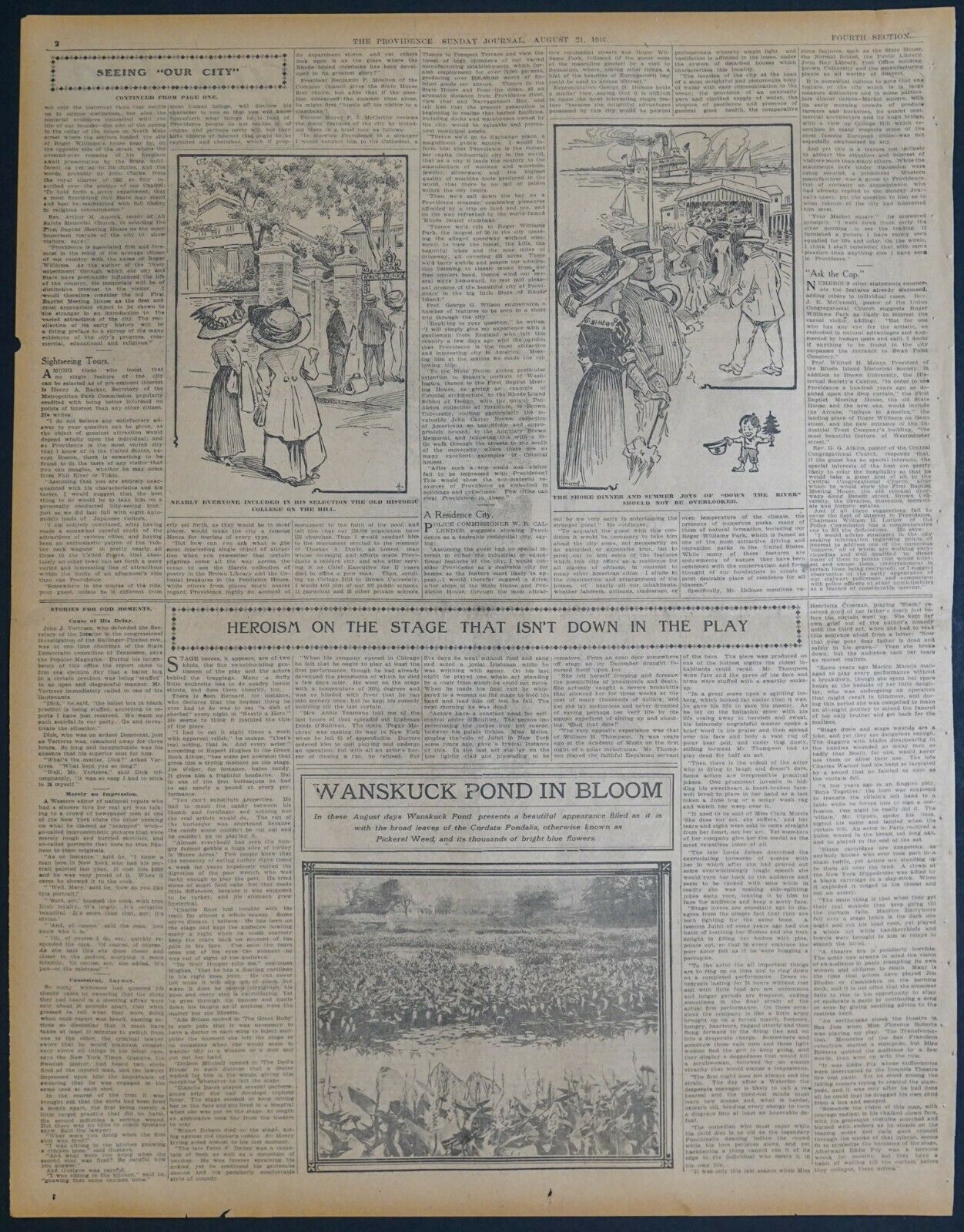

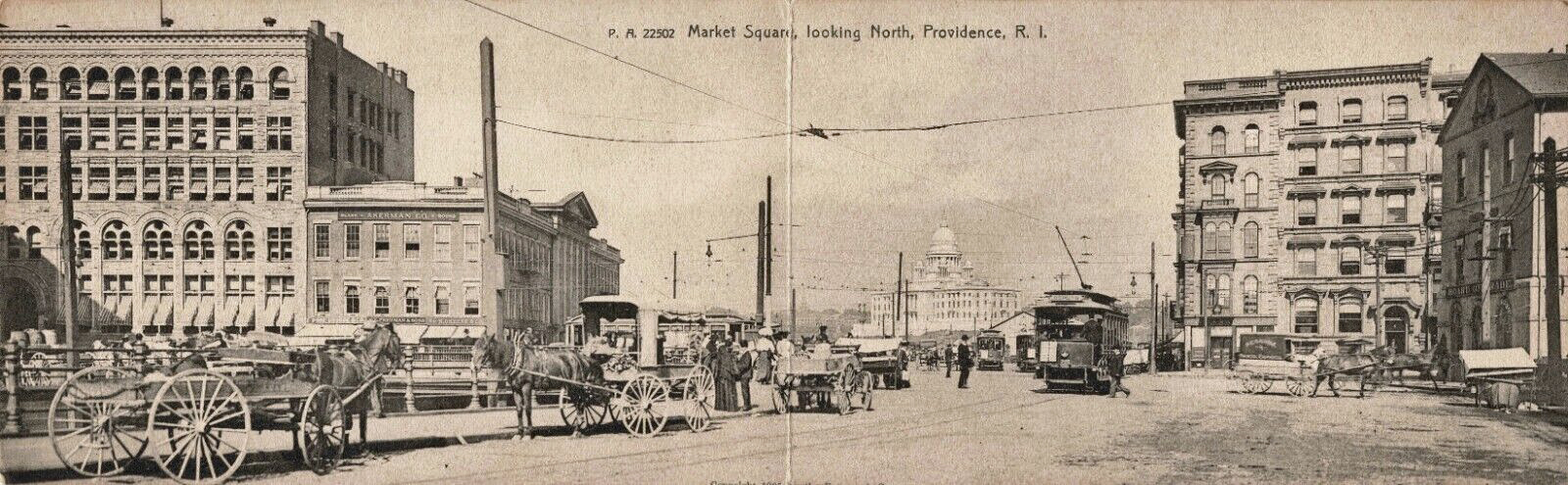

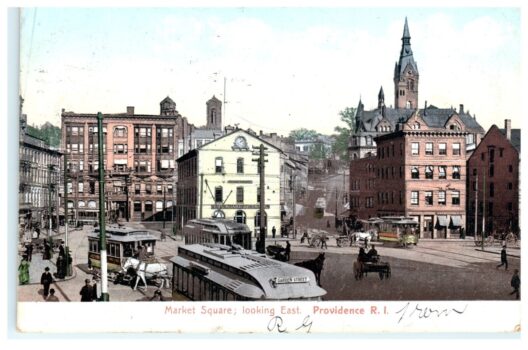

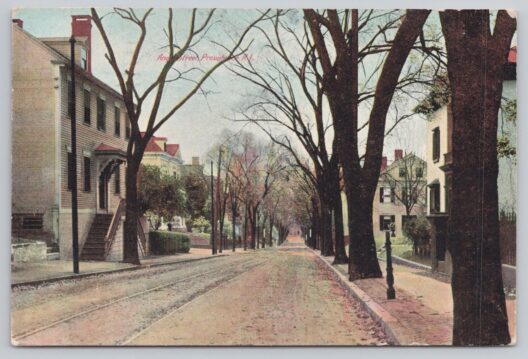

Anticipating the NecronomiCon and Armitage Symposium later in 2024, here’s another ‘Picture Postals’ post on Lovecraft’s Providence.

The Providence Journal daily newspaper played a significant part in Lovecraft’s coming of age. In his youth the paper informed him daily — most likely in its Evening Bulletin form — of his surroundings, in a way that adults would not have; it provided him with a slice of local public opinion in the letters pages; and it eventually offered him an outlet in print. A few examples will suffice. In 1906 Lovecraft used the letters pages to attack the ‘hollow earth theory’ of polar entrances to the earth’s interior, then still somewhat plusible. In 1912, the paper gave him his first published poem, the prophetic “Providence in 2000 A.D.”. In the 1920s he advertised in its pages for the return of his lost Houdini manuscript (whatever happened to that, one wonders)…

MANUSCRIPT — Lost, title of story, “Under the Pyramids,” Sunday afternoon, in or about Union station [Providence]. Finder please send to H. P. Lovecraft, 259 Parkside Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

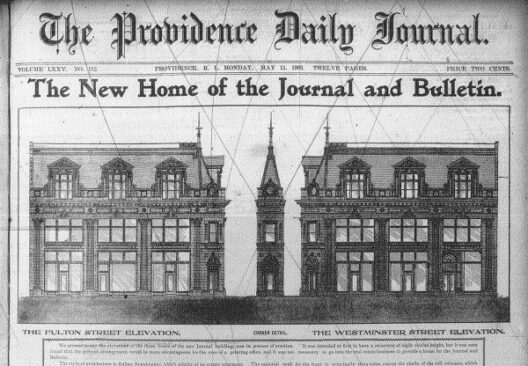

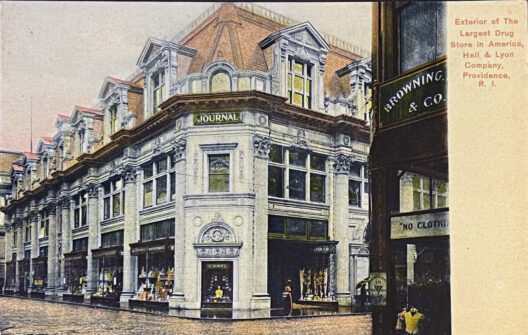

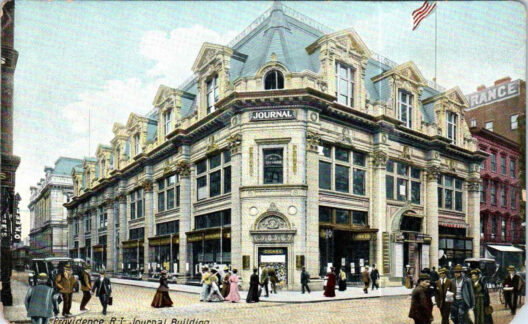

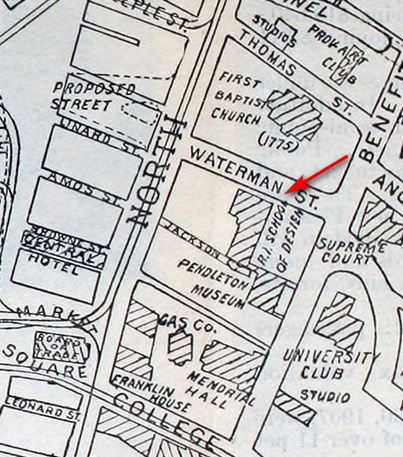

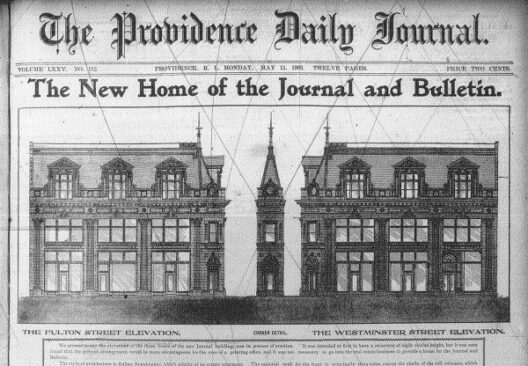

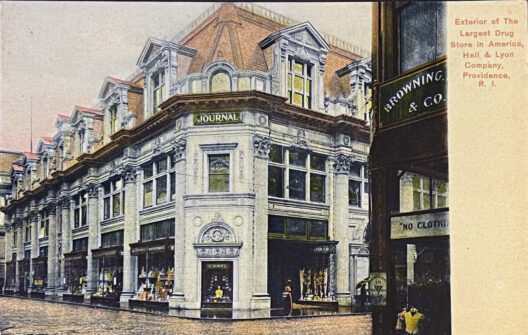

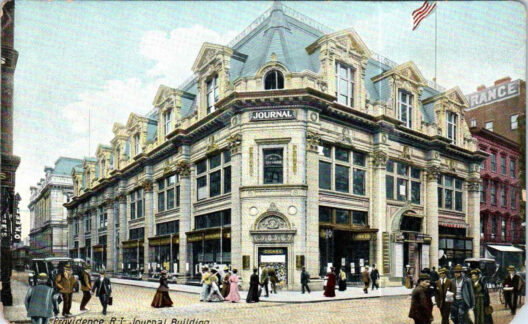

As such, its offices would have been a visual fixture in his early mental map of the city. These offices were new at the time he would have begun to aspire to publication in a newspaper. As we can see here, the offices seen in old postcards date only to 1903, when Lovecraft was around age 13 and would have been becoming increasingly aware of the wider life of his city…

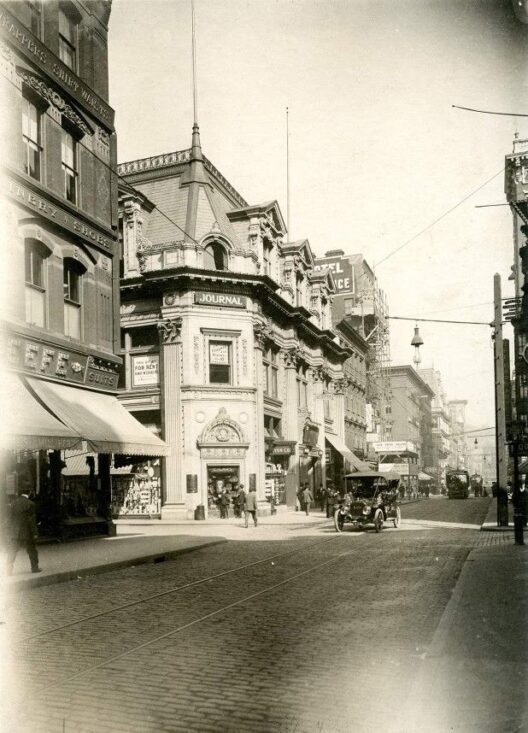

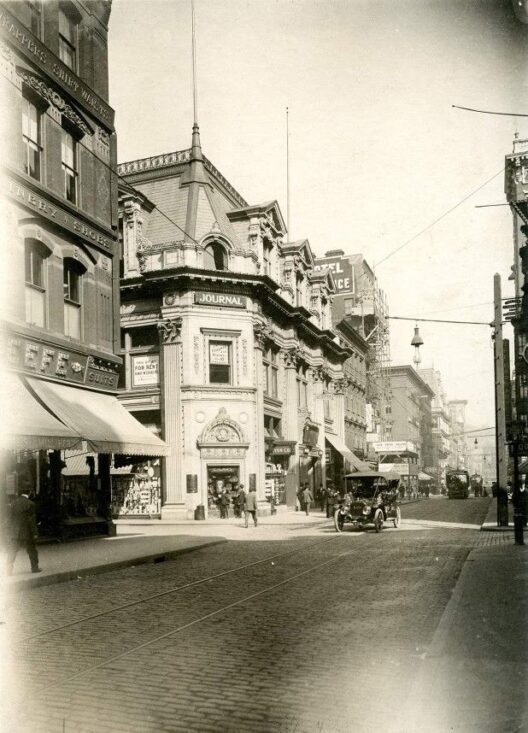

And here we see the offices from the sidewalk…

The lower floor was actually retail, and one card reveals their nature: Hall & Lyon, “the largest drug store in America”. It was one of a city chain of four Hall & Lyon drug stores at that time.

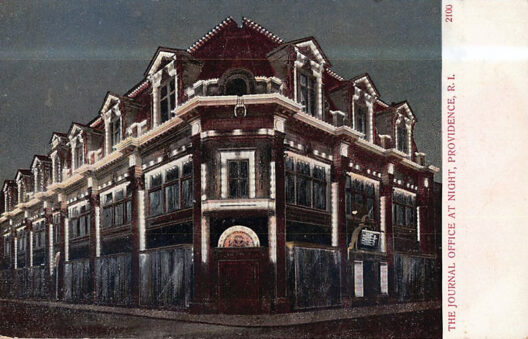

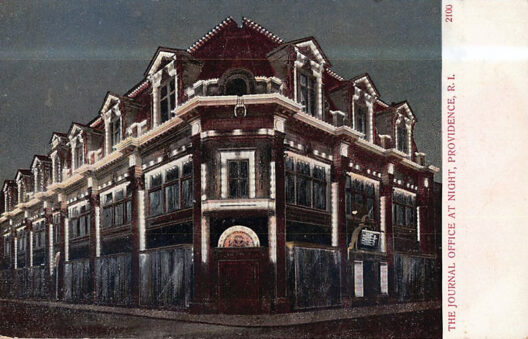

The upper floors were evidently illuminated when the offices were most busy, at night. The offices would not have been empty at this time. Journalism for a morning edition was then a nocturnal affair, and a journalist might work 8pm – 4am. Much of their work would then be reprinted, tweaked and updated, in the evening edition.

In 1918 Lovecraft commented to his friend Galpin re: the unusually large staff and number of pages, compared to a typical U.S. city daily of the period…

dailies hereabouts are inclined to run over that [standard 8-page] size to a considerable extent. The Evening Bulletin has never published less than 18 pages within my recollection, whilst it frequently runs up to 48. 30 is the average number.

He was still reading it 1922, even when away from city. In 1922 he wrote to Kleiner that he would… “read the file of the Evening Bulletin which had accumulated during my absence.” Joshi also states he read it while in New York City…

For the entirety of his New York stay, he subscribed to the Providence Evening Bulletin, [also] reading the Providence Sunday Journal (the Bulletin published no Sunday edition).

At 30 to 48 pages, this would have been a substantial daily read. Though we know he skipped the police reports and court reporting entirely. Given that ‘crime and grime’ can be a substantial proportion of local news focus, this must have reduced the time needed to read the paper.

But he probably read it closely, since he felt the papers were of “the very highest class” for local city papers (they sound like an equivalent of the UK’s Wolverhampton Express & Star in its glory days, perhaps). Indeed, he never discovered one that he thought was a better city paper. However he disliked the “poison of the vilest kind” which they sometimes carried as advertisements (in this particular case those of a “notorious beer-brewing corporation of St. Louis” which promoted an anti-prohibition message via a series of paid-for articles).

The paper must have partially made up for this, in Lovecraft’s mind, by doing something unthinkable for a city newspaper of today. Publishing what a modern newspaper reader would consider the ‘ultimate horror’… poetry. Sometimes he was even a paid contributor and (even more unthinkable today) paid for poetry, as when he had $5 for his lengthy poem “Providence” in the 1920s.

Here we see a good wide view of the 1903 building as the young Lovecraft would have known it…

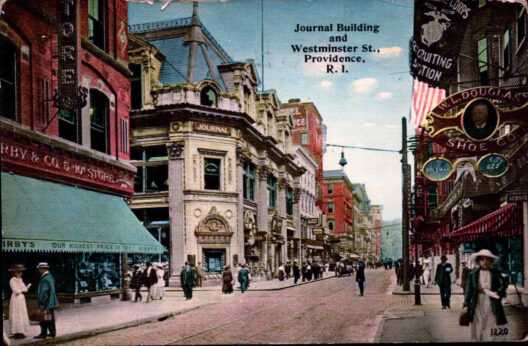

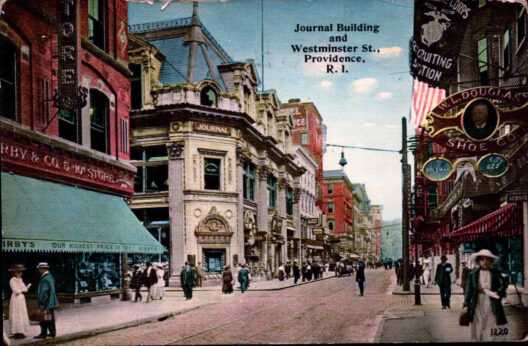

Another card seems to be later, with a ‘5c & 10c’ store established opposite, changing women’s fashions, and a military recruiting station flying the flag. One feels closer to the First World War in this picture. Could this even be the recruiting station at which Lovecraft tried his best to enlist?

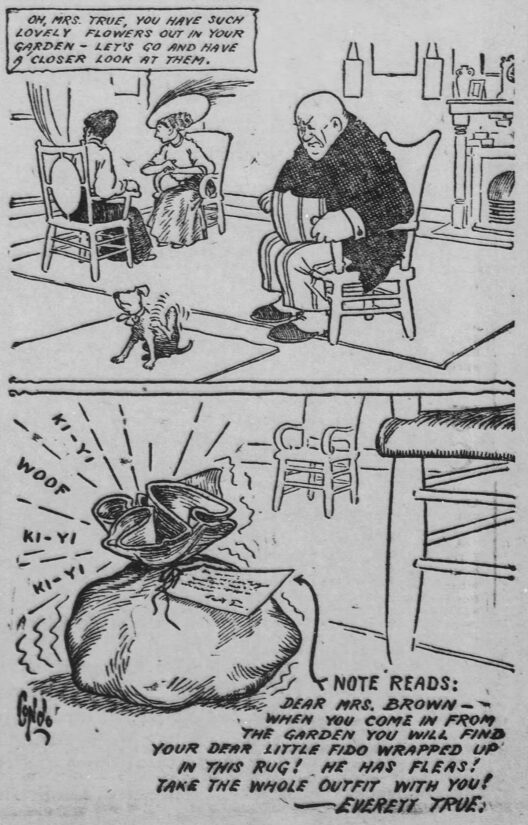

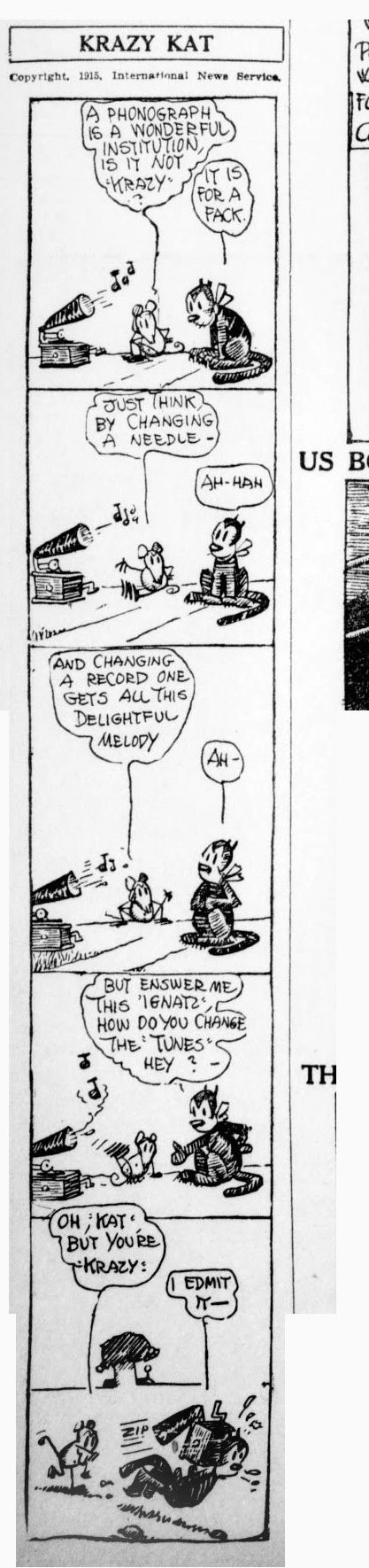

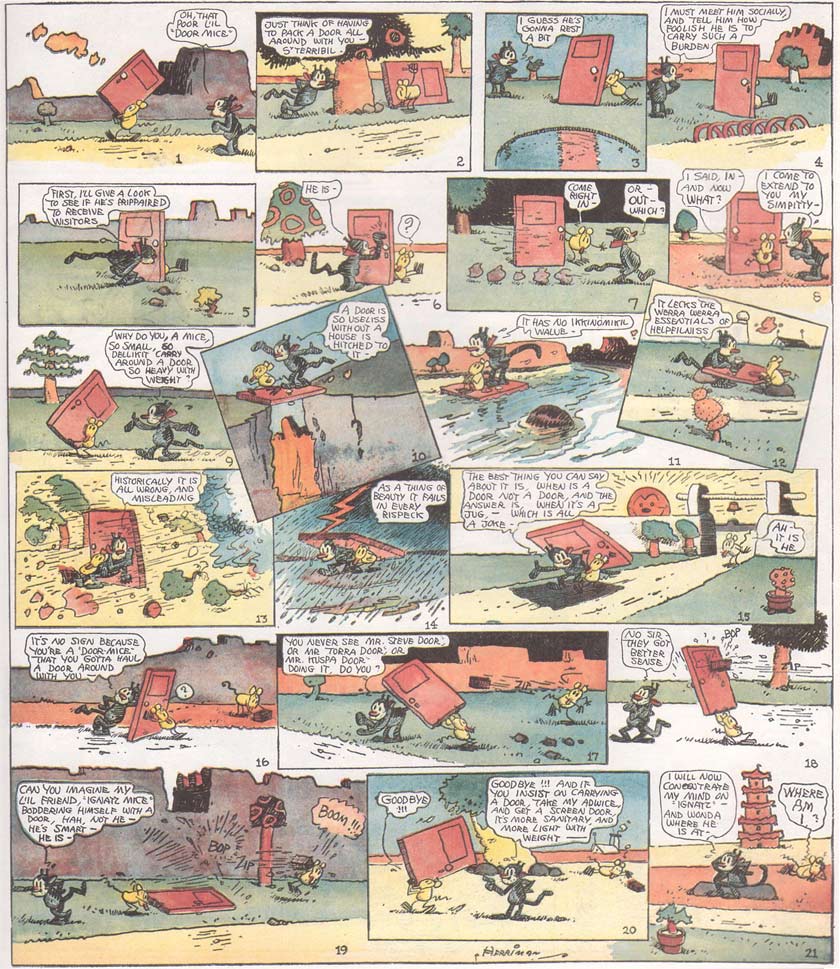

I can’t find any mention that the paper carried a comic-strip, spot cartoons, or even a ‘Sunday funnies’ page. So he would not have been enjoying things like Krazy Kat every day. Indeed, he wrote to Kleiner in 1917 that “the New-England dailies [newspapers] of the first rank do not use the conventional ‘comics’.”

The Journal thrived, and moved to larger offices in 1934. In the 1940s one of its journalists would become, essentially, Lovecraft’s first biographer.

The Library of the Rhode Island Historical association states… “The Library has complete runs of both editions on microfilm.” And for Lovecraftians, “A partial card file index (1915-1934) to the Journal is in the Reading Room.”

Note also that there is online access… “Full-text of locally-written articles from 1829-present can be searched, emailed, or downloaded from the Providence Journal on Newsbank”.