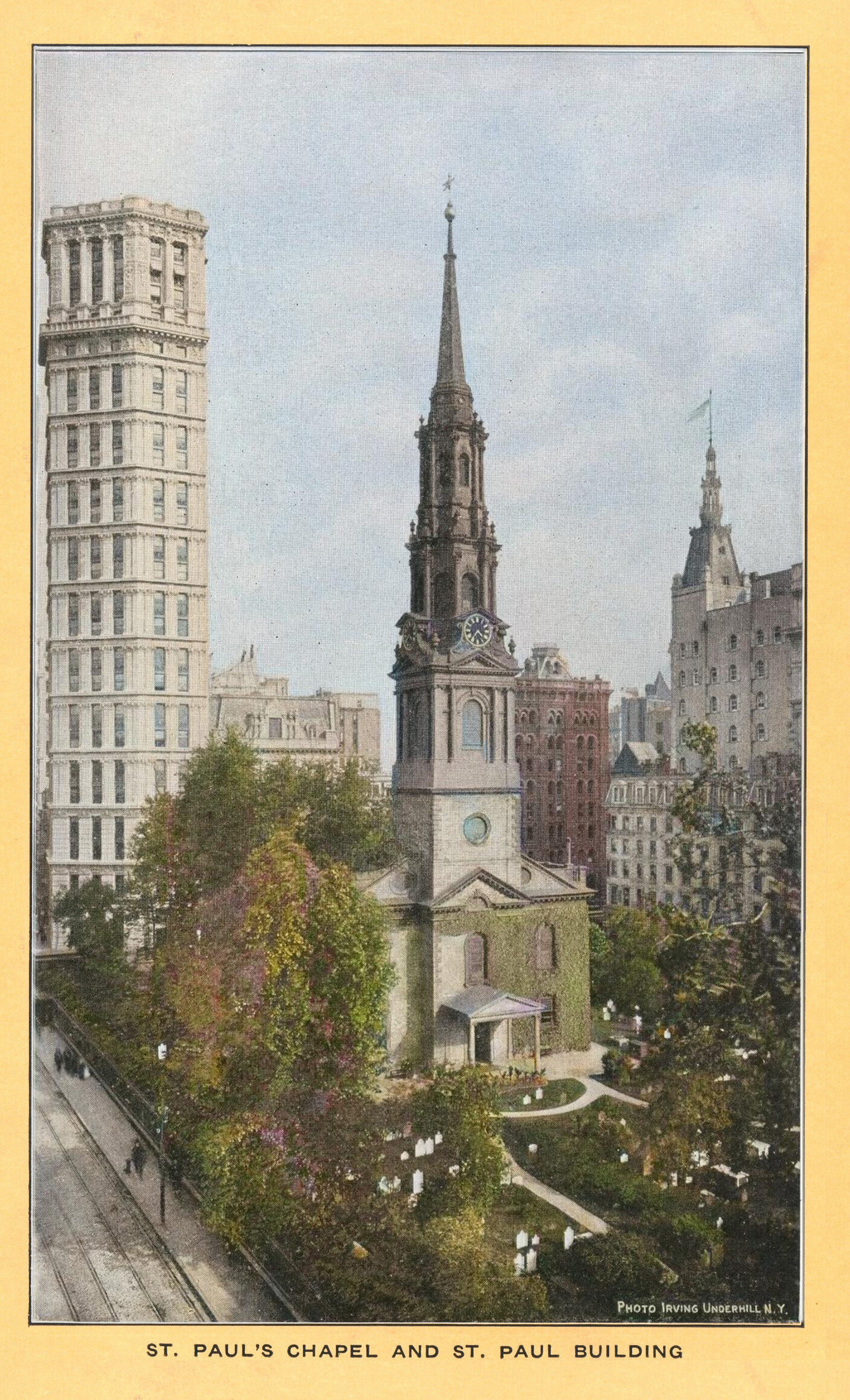

In these unhappy times, a look at a happy moment in Lovecraft’s life. Here are some views of the church chosen for Lovecraft’s wedding on the 3rd March 1924.

As Lovecraft had it…

St. Paul’s Chapel, Broadway and Vesey Streets, built in 1766, and like the Providence 1st Baptist design’d after St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields! [in London] GOD SAVE THE KING!

Neither Lovecraft or Sonia were religious, of course, but in those days a proper olde church it had to be — for a Lovecraft wedding. He appears to have chosen the place not simply for tradition, but also for its Colonial British architecture and family connections. It not only fitted…

most strongly Old Theobald’s traditional and mythological background

… but also echoed (in name only) the St. Paul’s church in Boston where his parents had married.

The cards and photos in this post are a little un-seasonal. March 1924 was famously very dry in New York, with very little early spring rain or snow, and the east coast down to Cheasapeake Bay was “warmer than normal” (Climatological Data for the United States by Sections, March 1924). Despite this and the city’s urban heat-island effect, early in March there would not have been the sort of spring/summer verdancy seen in these churchyard pictures. We might instead imagine a few hints of the very earliest new leaves on the trees, a sparse first flush of new grass after winter, and perhaps a few early un-opened daffodils.

We beat it to the Brooklyn borough hall, and got the [marriage licence] papers with all the coolness and savoir faire of old campaigners [… then ] Eager to put Colonial architecture to all of its possible uses … on Monday, March the Third, [I] seized by the hair of the head the President of the United — S. H. G. — and dragged her to Saint Paul’s Chapel, … where after considerable assorted genuflection, and with the aid of the honest curate, Father George Benson Cox, and of two less betitled ecclesiastical hangers-on [i.e. witnesses], I succeeded in affixing to her series of patronymics the not unpretentious one of Lovecraft.

Here we see the altar, albeit some decades later in time.

There were no friends or relations present…

Having brought no retinue of our own, we avail’d ourselves of the ecclesiastical force for purposes of witnessing — a force represented in this performance by one Joseph Gorman and one Joseph G. Armstrong, who I’ll bet is the old boy’s grandson although I didn’t ask him. With actors thus arrang’ d, the show went off without a hitch. Outside, the antient burying ground and the graceful Wren [designed] steeple; within, the glittering cross and traditional vestments of the priest — colourful legacies of OLD ENGLAND’S gentle legendry and ceremonial expression. The full service was read; and in the aesthetically histrionick spirit of one to whom elder custom, however intellectually empty, is sacred, I went through the various motions with a stately assurance which had the stamp of antiquarian appreciation if not of pious sanctity. Your Grandma, needless to say, did the same — and with an additional grace.

Of course, Lovecraftians now think of it as ‘a doomed marriage’. But perhaps it was not necessarily so. Had Sonia’s ill-advised independent NYC hat-shop been a success (and with the push of ‘the roaring 1920s’ economy behind it), and had her health then not have failed so badly, things might have turned out differently.

Pingback: The long walk… | Tentaclii