The latest Voluminous podcast reads some of Lovecraft’s public letters. Sent to Haldeman-Julius publications in 1923, the letters follow a call for lists of ‘the top 10 greatest names of all time’. Haldeman-Julius was the publisher of several magazines and the semi-notorious “Little Blue Books” pocket-paperback series. Operating from a large printing plant in remotest Kansas he became ‘the Henry Ford’ of cheap mail-order books, running a business that usefully and affordably punctured censorship throughout the 1920s and 30s.

An offline .MP3 download of the episode can be had via the Podbean listing.

Two things are immediately interesting in the letters.

The first is that it might seem that Lovecraft is pushing a Spenglerian view of imminent civilisational decline, but at that date he had not yet read Spengler. The famous 1918 The Decline of the West… “appeared in its English edition in 1926” in both the USA and UK. Obviously Lovecraft was well able to have his own ideas on the matter, but may have picked up enough from discussion and reviews to have an outline of Spengler’s gloomy ideas by early 1923. He writes to Galpin in 1932 that he read the first volume of Spengler in English… “some years ago with much attention & a great degree of acquiescence”. Joshi puts this reading at spring 1927, after having read a review of the book in 1926. But consider that Lovecraft also paid close attention to British ideas, and by 1923 the anti-colonial movement had taken up the cultural pessimism of many of the late Victorians — the idea that all Empires have natural cycles and that the British Empire could not last and would inevitably go the way of Rome. Hence, ‘better to quietly divest the Empire in an orderly way now, while we have the chance’, etc. Thus such arguments might be an alternative pre-Spenglerian source for such pessimistic ideas, paired with the general cultural pessimism of Schopenhauer, the French decadents, Nietzsche etc. At this point, recall, Lovecraft was still in the last part of his ‘decadent’ phase.

The second is of course the names on his ‘greatest of all time’ list. Most seem fairly sound choices for early 1923, and for what he admits is a rather sixth-form exercise not worth spending much time on. I won’t spoil the podcast’s letters by giving the names here, but they run thus…

Poet.

Philosopher.

Military general with cultural interests.

Military general and letter writer.

Poet and playwright.

Novelist.

Poet and story-writer.

Modern philosopher.

Modern philosopher.

Poet.

The last is the only really puzzling choice to English speakers today, since the French decadent / symbolist writer and editor Remy de Gourmont is almost unknown outside France. Lovecraft’s touchstone for Gourmont might be initially thought to have been the coy translation by Arthur Ransom (Swallows and Amazons) of A Night in the Luxembourg. But the dates don’t match. In September 1923, at the very end of his decadent phase, we know that Lovecraft read the book A Night in the Luxembourg (1919) (Selected Letters I, page 250). But this was after the letters he sent to Haldeman-Julius. What de Gourmont could he have read before that time?

Well, he had remarked to Galpin in June 1922 that… “Some day I guess I’ll give the immortal Remy the once-over — he sounds interesting.” Thus Galpin had read de Gourmont and told Lovecraft about it in glowing terms. The logical starter book for philosophic Paris-yearning Galpin to have been urging on Lovecraft would be the English translation of Philosophic Nights in Paris (1920). This had been issued in English by Luce, in Boston, a year after A Night in the Luxembourg and in a uniform edition with it. My guess would be that Lovecraft read Philosophic Nights in Paris late in 1922. He later quoted a line in English from the book, about beauty. Which admittedly is very slim evidence that he had read it, and especially since he undoubtedly owned the cheap Haldeman-Julius booklet The Epigrams of Remy de Gourmont (November 1923, translation of a 1919 book).

In early September 1923 Lovecraft tells Long that he’s been dibbling about with some random summer reading and that he has recently read the English-translation of A Night in the Luxembourg. This was after the letters he sent to Haldeman-Julius, and would thus not have influenced the ‘top 10’ list. He would have found this book equally well-suited to his own already-developed philosophy. Being a philosophical fantasy with play-like dialogue and “Epicurean interludes”, indeed “a crystalline Epicureanism” as translator Ransom explains. I would suggest that another part of the general appeal of de Gourmont may have been the idea that it was possible for an iconoclastic fantasy writer to strongly impact a nation’s intellectual thought. Lovecraft evidently saw this facially-disfigured hermit-writer as a Nietzsche-like kindred-spirit, a man apparently able to reduce a whole culture to rubble with a few strokes of his pen. Since Lovecraft-the-Nietzschian gleefully states, in the essay “Lord Dunsany and His Work” (December 1922), that through his writing… “Remy de Gourmont has brought a wholesale destruction of all values” to France. This is not hyperbole as de Gourmont does indeed appear to have had such a strong impact, being deemed the man who “spoke for his generation” while he was alive. But by the early 1920s the glittering game-players of French intellectual life had moved on.

Lovecraft barely mentions de Gourmont elsewhere, and I suspect the infatuation may have been short-lived. He didn’t read the man’s novel A Virgin Heart before he made a birthday present of it to Belknap Long in 1925. That must have been the 1921 New York edition. Admittedly, that he did not read it may not be proof of anything — it was a fat and apparently semi-erotic novel in translation. Even the most careful browsing of it might invite ribald joshing from Long that Lovecraft had ‘peeked at the naughty bits’ before giving the gift.

For those interested, a translated English sampler of de Gourmont’s fantastical fiction is From a Faraway Land (2019) by the indefatigable Brian Stableford. But I suspect that Lovecraft only knew the English translations of Philosophic Nights in Paris and A Night in the Luxembourg. The latter also gets a name-check in the European travelogue he ghost-wrote for Sonia… “I took care not to miss the splendid Luxembourg Gardens — reminiscent of Remy de Gourmont and countless other writers — which lie across the Boulevard St. Michel.”

What of influence? The first edition of Joshi’s Decline of the West does see a parallel between ideas in Luxembourg and “The Quest of Iranon” (February 1921), but no de Gourmont work was read by Lovecraft until after June 1922. One might also think of the Parisian setting of “The Music of Erich Zann”, but again that story was written in 1921.

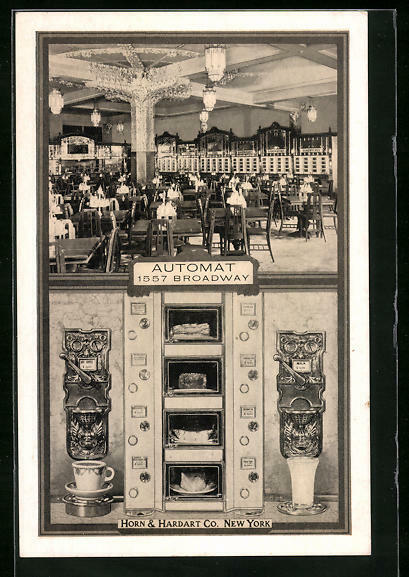

Tomorrow, a look at the links with Haldeman-Julius.