In an early letter to Galpin, dated 21st August 1918, H.P. Lovecraft recalled…

I began to study astronomy late in 1902 — age 12. My interest came through two sources — discovery of an old book of my grandmother’s in the attic, and a previous interest in physical geography. Within a year I was thinking of virtually nothing but astronomy, yet my keenest interest did not lie outside the solar system. I think I really ignored the abysses of space in my interest in the habitability of the various planets of the solar system. My observations (for I purchased a telescope early in 1903) were confined mostly to the moon and the planet Venus. You will ask, why the latter, since its markings are doubtful even in the largest instruments? I answer — this very MYSTERY was what attracted me. In boyish egotism I fancied I might light upon something with my poor little 2¼-inch telescope which had eluded the users of the 40-inch Yerkes telescope!! And to tell the truth, I think the moon interested me more than anything else — the very nearest object. I used to sit night after night absorbing the minutest details of the lunar surface, till today I can tell you of every peak and crater as though they were the topographical features of my own neighbourhood. I was highly angry at Nature for withholding from my gaze the other side of our satellite!

This tells us a number of things. It implies he was then aware of the Yerkes telescope. He must have been, even at a young age — since it was the Hubble Telescope of its day. It had been grandly exhibited a decade before at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, before being moved with much publicity to its domed home above Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Doubtless the Providence Public Library could have furnished pictures of such large telescopes for the boy Lovecraft, circa 1902-03, if he had not already seen the Yerkes in newspaper and magazine pictures.

But the quote is rather more interesting because it illustrates his initial and formative stance toward the “habitability … of the solar system”. By which he meant alien life, rather than future habitation by human colonists.

In this respect he obviously had hopes of making a discovery about the apparently cloudy and moist planet of Venus. This was then considered a somewhat likely habitation for alien life and was set to emerge as the Venus of pulp imagination, or the ‘Old Venus’ as some science-fiction historians now usefully call it. Undeniable evidence of its thick atmosphere had been obtained from Earth in 1882, it was warm and roughly Earth-sized and there were also what appeared to be markings on the planet’s surface. The prospect of life there was thus deemed quite possible. One even wonders if Lovecraft’s observations of Venus were partly non-visual, seeking to use his $15 spectrograph to detect something new and telling about the composition of the atmosphere? But, as he says in his letter to Galpin, others had the better equipment either way. Yet for all their immense telescopes and professional equipment, the professionals had still not settled the question of Venus by the time the adult Lovecraft returned to Providence from New York City. For instance here is The New York Times — then a sober paper of record — reporting in April 1927 on new methods of photographing Venus and detecting life…

But, as he recalls for Galpin, the moon was his chief interest. The moon was not, as we might now think, entirely without interest as a prospect for alien life. I have already glanced at the early theories about a pocket of atmosphere on the moon, and the theory’s implications for primitive life and the moon’s dark-side. The basic idea back then was that the moon’s immense natural ‘bump’ meant that a shallow atmosphere could just about persist on the dark-side, and some icy crater-lakes would form there. This theory appears to have been especially favoured by the Germans, and persisted there into the 1930s.

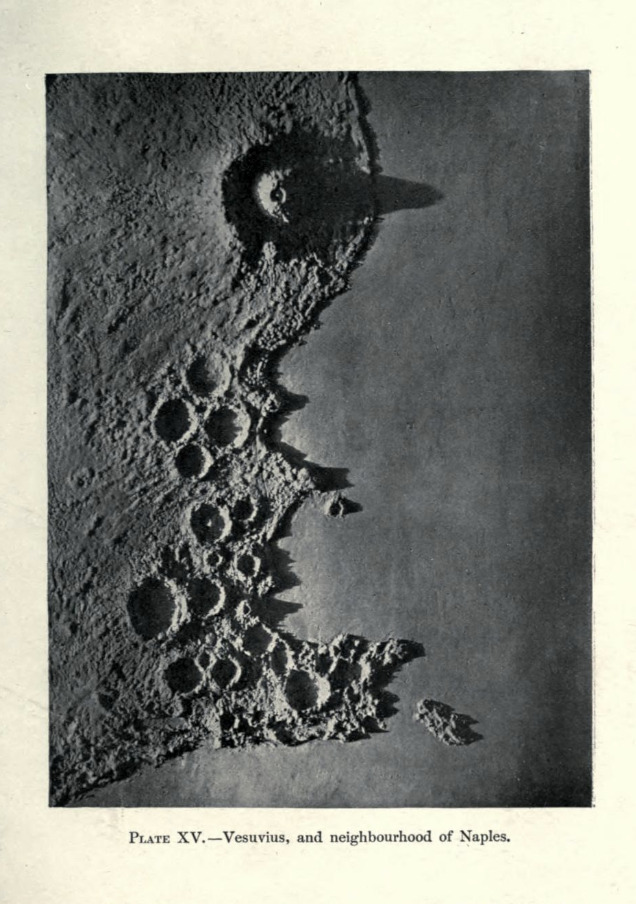

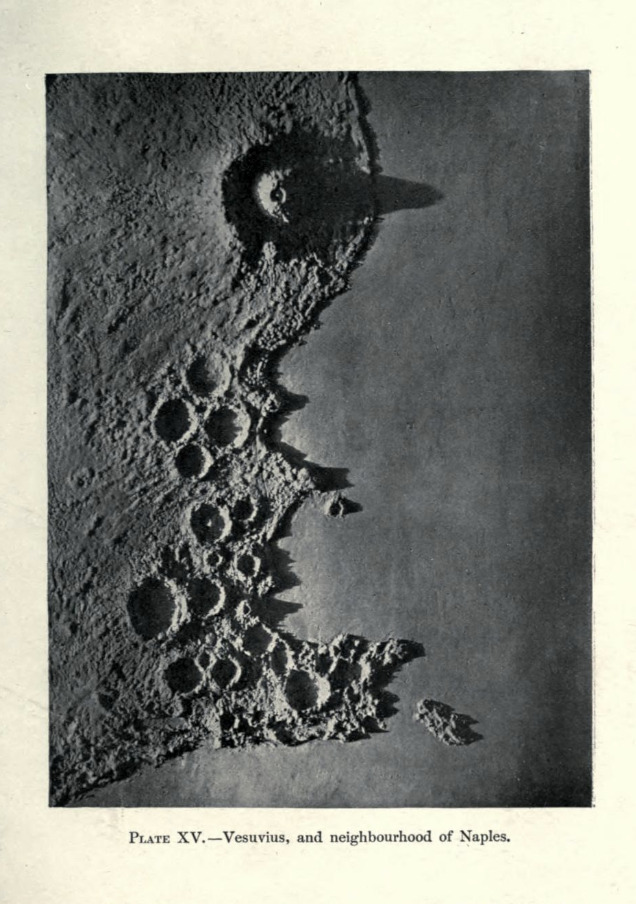

Now a little digging reveals that the young Lovecraft could also have been influenced by a moon book of the time, which had its own ideas about life. This was the illustrated book The moon, considered as a planet, a world, and a satellite, by Nasmyth and a co-writer. It was a key book, and the young Lovecraft had it in the 1903 un-revised fourth edition. The preface to this smaller and popular edition is dated May 1903 and The Bookseller lists it as available for purchase in early September 1903. Thus Lovecraft could not have had the book along with his new telescope (had either “early in 1903”, or in July 1903 according to Lovecraftian researchers). He would have had this worthy and useful book some months later either way, and perhaps it was even given as a Christmas present.

Such are the dates and the edition. What of the book’s ideas and influence? The book strongly supported and elaborately sustained a volcanic theory for the formation of the moon’s pockmarked surface. Volcanism then having obvious implications for things like subsurface heat. Because it implied magma chambers, networks of lava tubes, surface flow channels and so on. And at vast size too, since — as the book states — the moon’s large craters are immense and would dwarf those on earth.

Did Lovecraft subscribe to the theory? Yes. Lovecraft’s c. 1903 short note evaluating the likelihood of a competing theory of water-bearing “Lunar Canals” shows that he early accepted lunar volcanism. Also that he understood the volcanic activity to be relatively feeble by 1903…

“The lunar canals cover much less territory than the martian counterparts, this is doubtless, owing to the smallness of the moon compared with Mars, and therefore its feebler volcanic activity.” (“My Opinion as to The Lunar Canals”, c. 1903, my emphasis)

Was volcanism a crank theory? No. The volcanic theory of active crater formation reigned as a general scientific consensus until c. 1930, by which time some sustained doubts had become readily available in English. Yet its first serious challenge only came in 1949, long after Lovecraft’s death. Even then most scientists held to the consensus, until it was abruptly punctured by examination of actual rocks from the moon in 1965. Thus for most of his life, very likely for all of it, Lovecraft would have understood the moon’s surface to be actively volcanic in origin and nature.

This belief has certain implications. Do we glimpse here the spur for his intense moon observations? Quite possibly. If the boy Lovecraft could spot and observe an actual rare volcanic eruption in progress, and show the world the presence of a crater where before there had been none… he would have made his name as an astronomer.

What of the book’s opinion of life on this apparently volcanic moon? Nasmyth and his co-writer ruled out the possibility of “any high organism” on the moon’s surface due to the obvious lack of an atmosphere. Yet the book did tantalisingly suggest several possibilities for basic life:

i) Some form of ‘protogerm’ lying dormant, having sailed on the winds of space and landed…

Is it not conceivable that the protogerms of life pervade the whole universe, and have been located upon every planetary body therein? Sir William Thomson’s suggestion that life came to the earth upon a seed-bearing meteor was weak, in so far that it shifted the locus of life-generation from one planetary body to another. Is it not more philosophical [and assuming of a Creator] to suppose that the protogerms of life have been sown broadcast over all space, and that they have fallen here upon a planet under conditions favourable to their development, and have sprung into vitality when the fit circumstances have arrived, and there upon a planet that is, and that may be for ever, unfitted for their vivification.

ii) Some hardy form of vegetation able to survive intense cycles of heat and cold…

We may suppose it just within the verge of possibility that some low forms of vegetation might exist upon the moon with a paucity of air and moisture such as would be beyond even our most severe powers of detection.

After briefly considering these possibilities the book soberly concludes the moon is “barren” and that…

The arguments against the possibility of the moon being thus fitted for human creatures, or, indeed, for any high organism, were decisive enough to require little enforcing.

The words “barren” and “fitted” were well-chosen, since they leave open the question of the previously-suggested dormant and/or lower organisms. The book also leaves entirely un-examined the possibility of habitats in the sub-surface, in which the space-borne “protogerms” might have encountered a relatively warm (if apparently wholly dry and somehow non-gaseous) volcanic interior with its stable lava tubes.

Such lacuna would have been tantalising to the imaginative reader. I then suggest that here we may have some possible roots for Lovecraft’s later works, in terms of ideas such as:

i) a form of life that sails the star-winds and survives through space for cosmic time periods, before sifting down onto a clement planet to ‘vivify’;

ii) a hardy form of life, brought from the depths of space and (by implication) perhaps able to lie dormant for aeons in subterranean caverns. Only periodically brought to the surface by massive volcanism. A process akin, then, to the volcanic rising of R’lyeh in “The Call of Cthulhu”.

iii) the book’s volcanic ‘fountain’ diagrams and the idea of ‘protogerms’ arrived from space might both seem to evoke “The Colour out of Space” in its water-well.

I don’t say these were direct inspirations, later dredged from memory and made to serve Lovecraft’s mature fiction. But they would have been formative in shaping the broad contours of Lovecraft’s earliest cosmic imagining.

Incidentally, his yearning to see the dark side of the moon may even hint at a boyish theory about life existing there. In the absence of the lost boyhood story that he set there we can’t know much more about that. Yet knowing that he held to the volcanism theory suggests one obvious path the story could have taken — the discovery of volcanically melted crater-lakes on the dark side (his boy explorers had apparently needed their carbide lamps, implying they had stepped over the dividing-line) under a thin atmosphere.

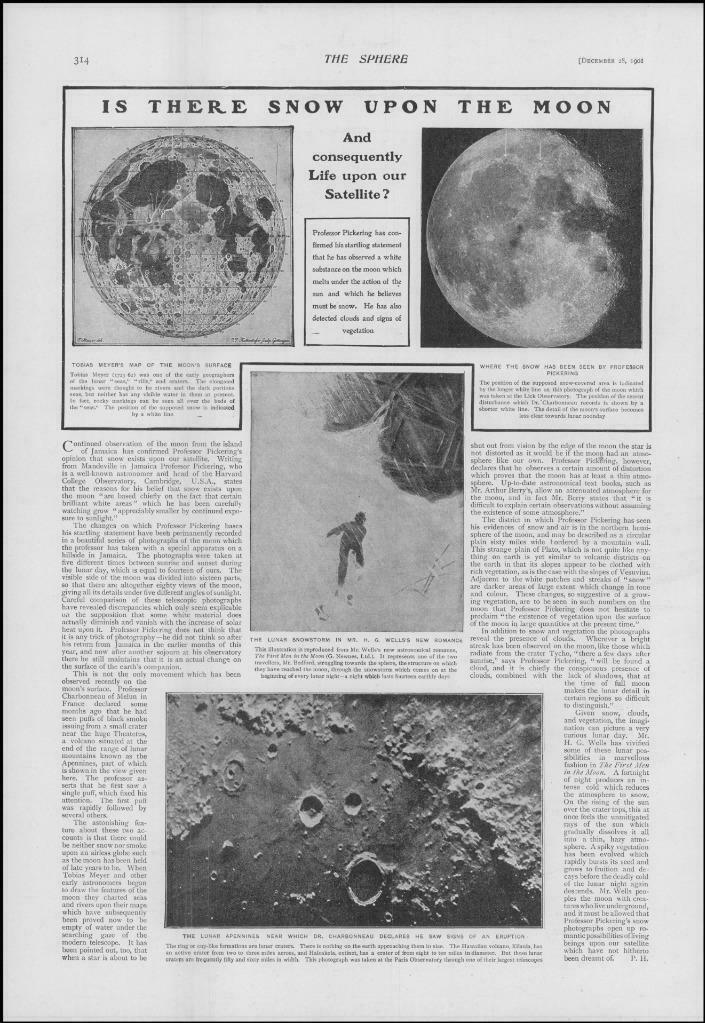

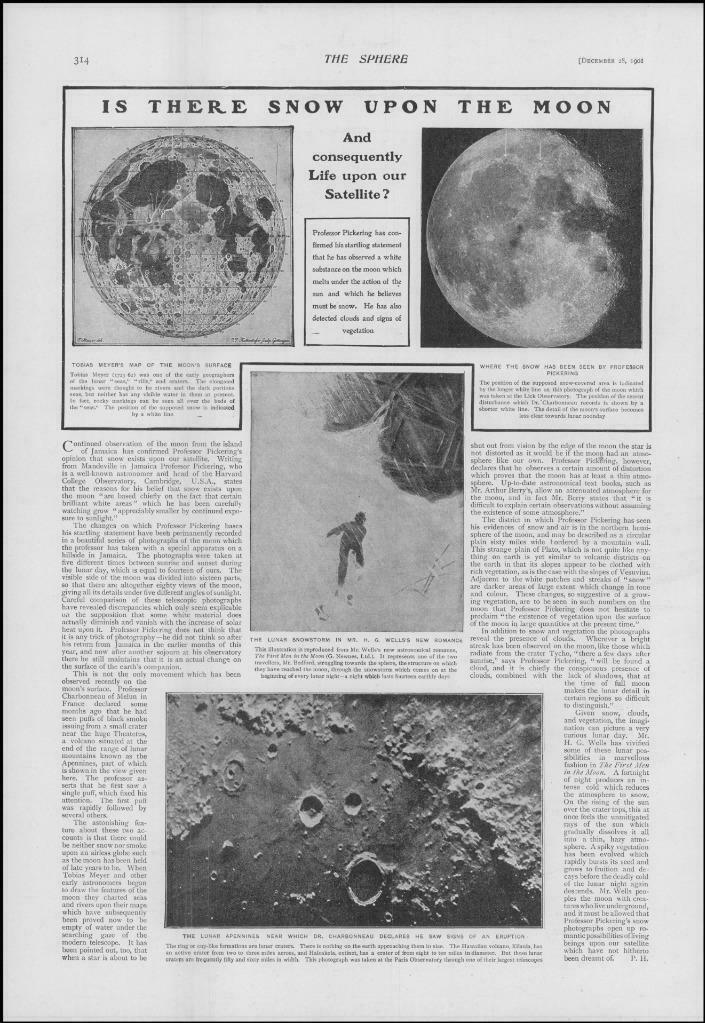

What of ‘moon life’ claims made by others? Here I give readers a quick flavour of Prof. Pickering’s ‘snow’ ideas, related to his lunar ‘canals’ idea, via a glimpse of a full-page article in The Sphere for Christmas 1901…

One can see how it would be easy to dismiss such things. Claims of observations of active primitive plant growth along snowy “canals” (or “streaks of vegetation” on the surface as Lovecraft described them) were indeed dismissed early by Lovecraft in his “My Opinion as to The Lunar Canals” (1903?). However much the glittering mountains might look like snow in photographs, water was not detectable from earth. Without water to sustain life, such things as ‘canals’ and ‘vegetation’ could not be. If the “Lunar Canals” text is correctly dated, then I would suggest it was written in late 1903 and under the direct and countering influence of the 1903 reprint of Nasmyth’s moon book.

See the Lovecraft Annual 2019 for a fine essay detailing Lovecraft’s reactions to Professor Pickering’s claims for the ‘lunar canals’ and more.

Yet ‘life on the moon’ was not then an either/or choice. One might sensibly discount questionable ideas such as immense banks of “snow” or “canals” and “vegetation”, while not entirely giving up hope for moon habitats of some sort. For instance, five years after his “My Opinion as to The Lunar Canals” we find Lovecraft even more certain of the apparent evidence for “active volcanism” on the moon, in his essay “Is There Life on the Moon?” (1906). But he has evidently become, after several years of personal observing, far more open to the idea of an active moon. He now aligns himself with some of Pickering’s ideas and the German ‘bulge’ idea, by musing on a “thin” atmosphere and surface frost forming on ridges…

Today [certain moon changes are] generally accepted as the work of active volcanism. Now no volcano can operate without atmosphere, but there could easily be a thin gaseous envelope undetected from the earth. The “lunar rays”, i.e. long, brilliant streaks radiating outward from some of the craters, have always been a puzzle to astronomers. Numerous theories have been promulgated concerning their origin, some saying that they are cracks in the moon’s surface while others maintain them to be streaks of lava, ejected in the remote past from the craters which they surround. But the latest and most startling theory is that they are deep furrows filled with snow. This seems incredible at first sight, considering that there are no clouds on the moon; but when we reflect that little more than hoar frost would be required to produce the glittering appearance, the theory becomes more acceptable. For this theory, the world is indebted to Prof. William H. Pickering of Harvard, the greatest living selenographer [i.e. Moon geographer].

Lovecraft could not believe in Pickering’s vegetative “canals” back in 1903, and he still could not do so. Nor could be believe in a widespread Christmas-y “snow” on the moon. But by 1906 he can at least believe in thin lines of “hoar frost” along the crater rays, while also making a nod to active volcanism operating with a thin atmosphere. These claims then set the reader up, in the same “Is There Life…” essay, for Lovecraft’s far bolder observation that in…

a deep, winding chasm [on the moon] called “Schroeter’s valley” can be seen the only active and ocular proof of seismic conditions. There an assiduous observer can detect peculiar clouds of moving whiteness, which the up-to-date selenographer interprets as nothing more or less than smoke from an active crater! These clouds are often so dense as to obscure neighbouring objects.”

He did not discover this likely spot on the moon, with its apparent implications for a sub-surface habitat for life. Nor was he the observer of the shoggoth-like “clouds”, as his article might vaguely seem to imply. Because it was almost certainly the August 1905 article “Life On the Moon” in Munsey’s Magazine that alerted him to this vast chasm and its “clouds”. I have dug the article out of Hathi (regrettably missing its first page on the scan, presumably torn out for its opening moon illustration). The text reveals that the Schroeter’s valley “clouds” observer was actually Pickering, and the author was generally highly supportive of Pickering’s ideas. This was probably the sort of popular article that had made Lovecraft receptive to some, though not all, of Pickering’s ideas.

Did Lovecraft read the article? It seems highly likely to be the source for his very similar Schroeter’s valley “clouds” observation, and we know he was reading Munsey’s Magazine from at least 1903…

In the only extant issue of [his] Rhode Island Journal of Science & Astronomy (September 27, 1903) makes reference to an article by E. G. Dodge entitled “Can Men Visit the Moon?” in the October issue of Munsey’s Magazine, which if nothing else indicates that Lovecraft was reading the journal at least as early as this. (Joshi, I Am Providence)

So there are now two moon articles known from Munsey’s Magazine, “Can Men Visit the Moon?” (1903) and “Life On the Moon” (1905). It’s quite possible that he read others there that have yet to be discovered.

As it happens it seems that we now know that the Moon was indeed volcanic and had a thin periodic dark-side atmosphere, but that the last such events were some two billion years ago. That ancient process likely created today’s large flat dark ‘mares’ or ‘seas’ as lava flows, and also rather usefully left us billions of tonnes of ice at the poles.

After 25 years away, Lovecraft’s imagination would return to the moon. Though not to encounter fungi-litten volcanic caves, or insect-philosophers crawling over the dark side under a feeble atmosphere, or even cloudy proto-shoggoths oozing from “a deep, winding chasm”. Instead in his Dream-quest tale he deemed the moon’s surface — at least as dreamed of in the Dreamlands — to be the poignantly still and desolate haunt of the cats of Ulthar. With strange and unspecified attractions to be found on the dark side.