Notes on The Conservative, the amateur journalism paper issued by H.P. Lovecraft from 1915-1923.

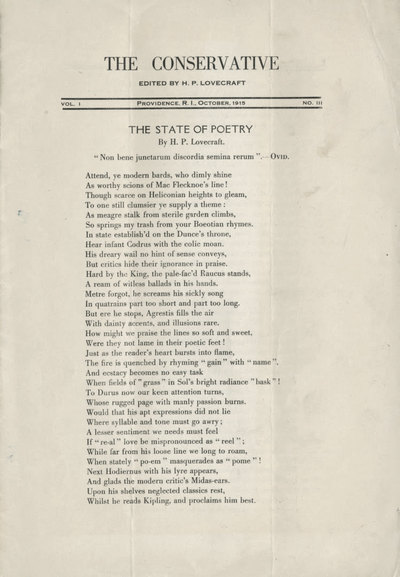

Part Three: the October 1915 issue.

Lovecraft has now issued his third issue of his own amateur paper The Conservative. Is it a Halloween ‘horror’ issue? Let’s find out.

He opens with his poem on “The State of Poetry”, headed by a line from Ovid which translates for sense as “Ill-mated things have discordant offspring”. This might seem to some to hint at key themes in his future fiction. The poem ushers forward a series of would-be bards to perform for a king, each bard offering his own form of poetic ineptitude or gross error of topic. One suspects the readers of The Conservative would have been well be able to identify each amateur journalist thus given their turn on the stage. These are sometimes well masked, with names such as “Mundanus”, or even left un-named as mere Whitman-esque “degen’rate swine”.

Note the line of poetry “Ablest is he who in rhyming can reach / The Lofty coarseness of a Cockney speech”, something that Lovecraft had experienced in his own city of Providence at the astronomical Ladd Observatory, in the company of the “affable little cockney from England” John Edwards. Lovecraft ends his verse by suggesting the true poet will do best in chaste seclusion (such as his own, hem hem), restoring ancient times with his imaginative ‘fancy’ and learning much from the lost Golden Ages of creativity such as the England of Shakespeare or Johnson.

His essay “The Allowable Line” naturally follows from the poem. It is headed by another untranslated line from the Roman poet Horace. A line which translates for sense as “On discovering dazzling brilliance, disregard the flaws”. In the essay he continues his debate with Kleiner, begun in the previous issues and continued in correspondence, on the “allowable rhyme”. He tracks this through history, giving a basic outline of its once-common use in English poetry, and then the later emergence of stricter rhyming. In this we also have the sense that Lovecraft has read the work of all those he names, and with due attention. Not that he liked all of them, and for instance he calls Erasmus Darwin’s poetry “pompous”. Though if all he recalled, and hazily so (“Darwin’s ‘Botanick Garden’ … my early reading”) was The Economy of Vegetation, then he may not have realised that the slump in the middle of this book is likely the result of Darwin’s collaborator slotting in her own unheralded verses.

His “Editorial” bites back against the “insulting insects” that have begun to infest his mail-box, and he threatens to publish their letters with “original style, spelling, grammar” in future. The short article “The Conservative and His Critics” naturally follows, headed by more lines from Horace, which can be translated as “It is better, I warn you, not to make me touchy”. Then some short poetic ripostes to politically pro-German lines of wartime verse which had attracted Lovecraft’s special ire.

We then come to the meat of the issue, with the long essay “The Renaissance of Manhood”. Here Lovecraft forensically identifies the types of pacifists who oppose a just and necessary war, and suggests their motivations. One feels he will have more to say on the topic in future. Though as S.T. Joshi has observed, his own attempts at patriotic poetry will fail to rise above mediocrity.

The essay “Liquor and its Friends” reveals that he broadly subscribes at this time to the ‘trickle-down theory’. Those at the top of society must first set an example, “which will then work downwards, as if through gravity”.

His thoughts on “The Youth of Today” follow. He welcomes the postal approach of “schoolboys of today [who] fear not to speak as they think”, and here we learn of how he first encountered his new young protege David H. Whittier.

“Symphony and Stress” appears at first sight to examine another side of amateurdom, in which amateur papers were “the product of a small circle of cultivated ladies”. Yet mid-way he compares this to Lockhart’s anti-rum paper Chain Lightning which vividly recounts “unspeakable evil” among the alcoholics and “horrors utterly beyond the realization” of the sheltered ladies. All drawn from Lockhart’s experiences in his own town. Lovecraft ends by asking the ladies to forbear in their mild criticism of negative-minded “buzzards” in amateurdom. Each has their place, and may do good in their own way.

He briefly lauds some improving amateur papers from youths, and especially notes Basinet’s paper The Rebel. Lovecraft states he knows Basinet personally, but what goes unsaid is that the lad was one of the largely Irish group of Providence amateurs — later to be so ably documented by Ken Faig Jr. Here Lovecraft notes that Basinet has recently switched his leftist beliefs from socialism to anarchism. Dunn, of the same local group, is also noted in the context of discussions of the ever-vexed Irish question. Lovecraft seems to be of the opinion that “Ireland is now an equal and integral part of the British Empire” and thus (presumably) nothing more need be said.

A back-page poem by John Russell titled “Socialism” marks the end of the issue. Russell was a long-distance Lovecraft correspondent (West Tampa, Florida) from 1913 through 1925, encountered via a vehement debate in the pages of The Argosy. This 1915 poem foresees the “stagnant pool” that society would become if a wise man and a fool were to receive the same treatment and income in a vain attempt to enforce a socialist economy. Also the way that socialist leaders, inevitably authoritarian, would start to find underhand ways to “grab the most they could” from the masses.

The Halloween horrors that some Lovecraftians might have been expecting of an October issue are thus… not here. Yet in a way, it is a horror issue of a sort. There are “insulting insects” in Lovecraft’s mail-box; he details some of the very real “unspeakable evil” which emerges from alcoholism; and finally anticipates the looming horrors of socialism — horrors which were to become manifest soon after Trotsky’s Moscow coup in 1917.

Overall one has a strange sense of familiarity with the present day. An ugly mix of high-flying philosophical debate and pro-enemy sympathies during wartime; a hazy vision of socialism which seduces a vocal minority among the young; a mass of hide-bound reactionaries unwilling to adapt to the new modernity; while lone grassroots voices battle for the truth about ruined lives and families in their own town. Also a tendency among creatives toward a complacent withdrawal from it all, into a rose-tinted myopia in which beautiful and well-formed poetry is everything.