British Museum, possibly 1920s.

In this week’s ‘Picture Postals’ post…

A dark and monstrous lizard-shape that glides

Along the waters of the inland tides

These are the concluding lines from a Weird Tales poem by Frank Belknap Long, later quoted by Lovecraft in corresponding with Long about dinosaurs in 1930. The master had been kindly sent a dinosaur bone from California. (Incidentally, Long’s original poem had “Upon”, not the improving “Along”. So this might count as a little expert Lovecraft micro-revision).

Given the visual appearance of young Lovecraft’s nightmarish ‘Night-gaunts’ one has to wonder what part an early exposure to the imagery of the pterodactyl might have unconsciously had on a very young H.P. Lovecraft. First, what are the dates for this? Well, he began to have nightmares about them at five and a half, so a visual influence from print would have to have been before 1896.

It is of course possible that the black crepe and mourning silks worn by the family on the death of ‘Rhoby’ partly inspired the night-gaunts. Lovecraft was born August 1890, and therefore would have been five and a half in February 1896. ‘Rhoby’ (about whom more next Friday) died 26th January 1896, and the mourning presumably continued until the springtime. Thus the dates fit remarkably well, if one assumes a direct reaction in the boy’s nightmares after a few weeks. However, it must be asked what prior template he might have had. A leathery flying form onto which the family’s sombre rusting black crepe could have been ‘pinned’ at the moment of inception, so-to-speak.

Lovecraft much later, in 1916, speculated that the night-gaunts might have been influenced by the ‘man-devils’ of Dore…

I used to draw them after waking (perhaps the idea of these figures came from an edition de luxe of Paradise Lost with illustrations by Dore [1866], which I discovered one day in the east parlor).

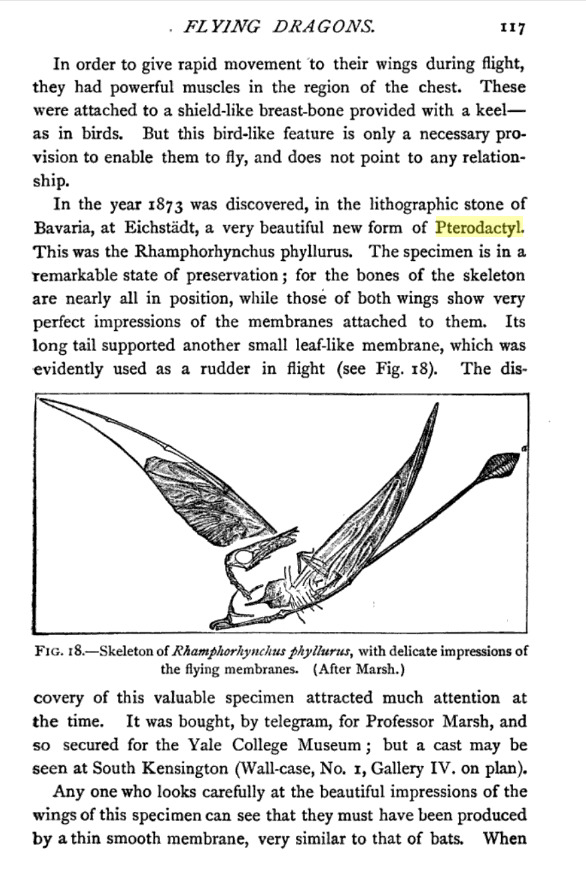

But it is at least worth considering if he might have had a template elsewhere. In popular pterodactyl imagery, and thus had an earlier and forgotten impression of them, for what young boy is not fascinated by such things. Could he have seen them at that time? Yes. Judging by the book Extinct Monsters: A Popular Account (1893) the creatures were quite well known the late Victorians, and a science timeline shows that the first complete scientific description being given in 1891. Presumably this ‘flying dragon’ arousing a certain interest among the public, and among boys in particular. So the timing is perfect there, if they were indeed transmuted into night-gaunts by Lovecraft’s nightmares.

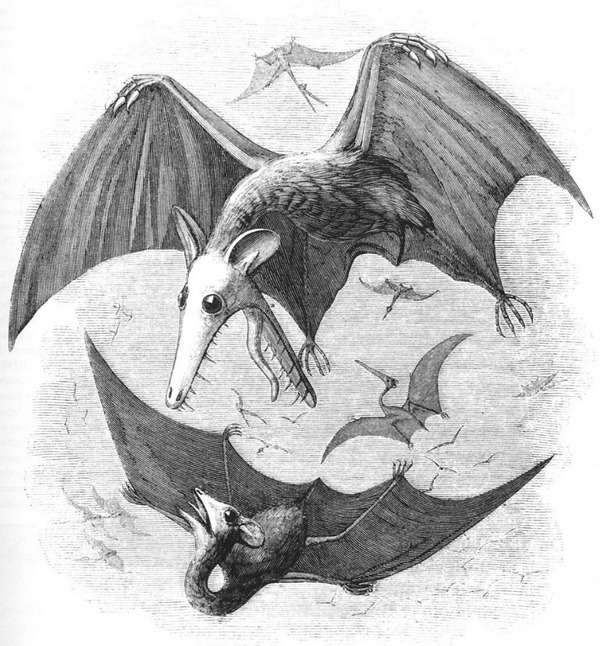

Indeed they had been visualised in living flight (wrongly, but somewhat zoog-like) as early as 1843, as here by Newman…

Thus by the early-mid 1890s they would have been included in most general encyclopedias (as Pterosaur, Pterodactylus, Pteranodon, Pterodactyl, etc), and we know that Lovecraft was poring over at least one of those a little later…

With the insatiable curiosity of early childhood [circa age 8], I used to spend hours poring over the pictures in the back of Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary — absorbing a miscellaneous variety of ideas. After familiarising myself with antiquities, mediaeval dress & armour, birds, animals, reptiles, fishes, flags of all nations, heraldry, &c., &c.,

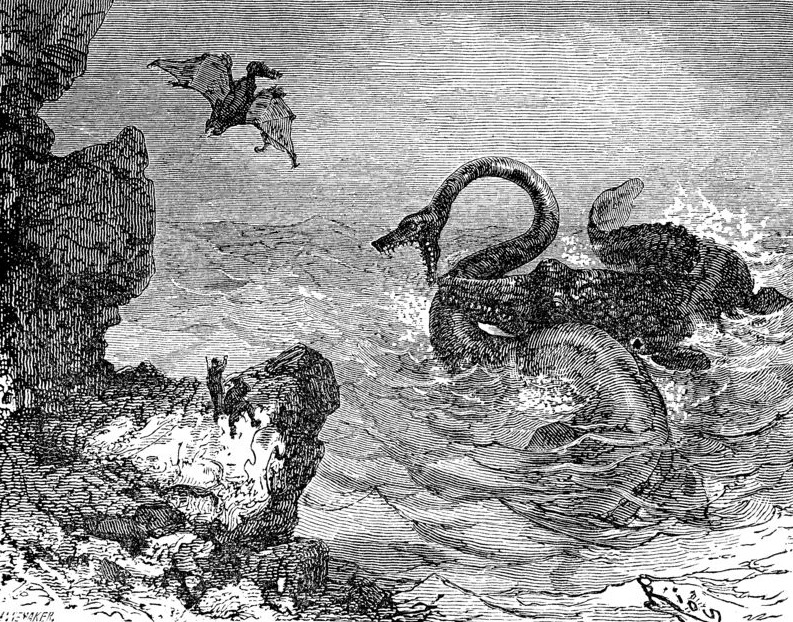

They also feature briefly in Verne’s novel A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1871), illustrated and seen during the raft voyage chapter…

the Pterodactyl, with the winged hand, [was seen] gliding or rather sailing through the dense and compressed air like a huge bat.

Joshi’s “I Am Providence” notes of the boy storyteller…

Lovecraft admits to being a “Verne enthusiast” and that “many of my [earliest] tales showed the literary influence of the immortal Jules”.

It is thus not impossible that he was at an early age at least browsing ‘the monster-pictures’ in the family edition of Verne, if not actually reading them yet.

The other possibility is that a museum in Boston might have had a life-size reconstruction or vivid diorama circa 1894. But I can find no trace of such in Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1910, and Richard Fallon’s new Reimagining Dinosaurs in Late Victorian and Edwardian Literature (2021) indicates a general 1900 start for major modern museum dinosaur shows in East Coast America, while also lamenting that…

The significance of dinosaurs for general audiences during the late nineteenth century, when dinosaurs were morphing from British lizards to multiform American monsters, however, has hardly been studied. … The lack of detailed attention to dinosaurs in the literary culture of the turn-of-the-century period, and especially the 1890s, is surprising, given that these were the decades in which the word ‘dinosaur’ first became meaningful to general audiences.

So my suggestion is possible on the dates, but cannot now be proven. There is indeed further negative evidence. If this night-gaunt -like creature did make an early and vivid impression in Lovecraft’s very early childhood, then it does not surface later — at least in the original form. Since Lovecraft only makes two fleeting explicit mentions of the creature in fiction…

This was my first word of the discovery, and it told of the identification of early shells, bones of ganoids and placoderms, … dinosaur vertebrae and armour-plates, pterodactyl teeth and wing-bones …” (from “At the Mountains of Madness”)

I fancied I could vaguely recognise lesser, archaic prototypes of many forms — dinosaurs, pterodactyls, ichthyosaurs,” (from “The Shadow Out of Time”)

The pterodactyl does however make a brief and central appearance early in the earlier long essay (“Cats and Dogs”)…

“I have no active dislike for dogs, any more than I have for monkeys, human beings … or pterodactyls.”

Neave Parker postcard for the British Museum, probably early 1950s.