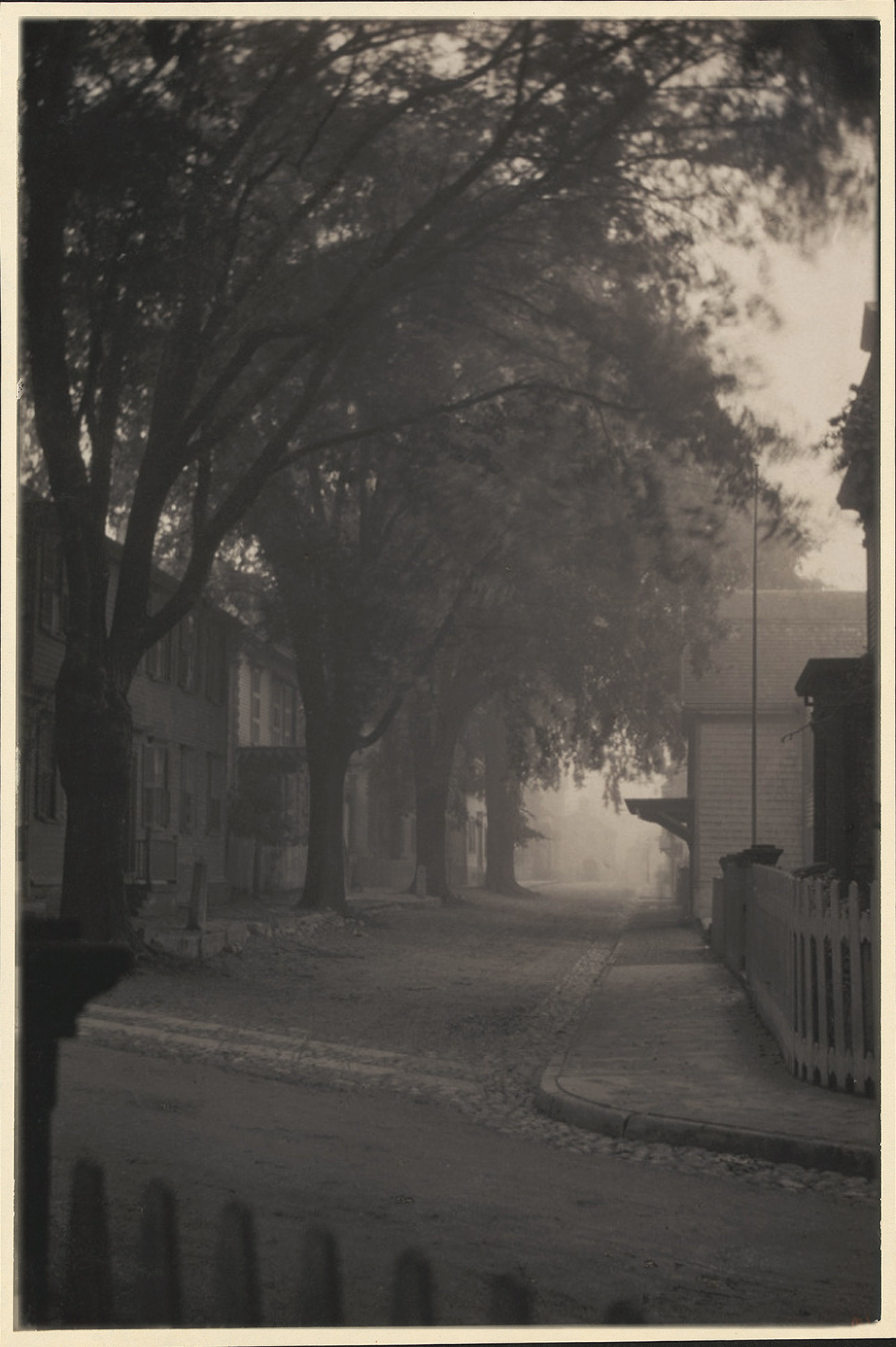

Last week’s ‘picture postal’ had a setting of quiet streets and mistiness. This week’s post continues with the same theme, evoking the ‘end of season’ shawl that many New England places would have worn by September.

I. The mist in New England.

The picture also evokes the distinctly seasonal nature of Lovecraft’s own travels and visits. His annual cycle, of summer walking followed by a winter hermitage, was partly due to his extreme sensitivity to the cold. By the early 1930s he was becoming the old man he had once feigned to be, and appears to have become both more susceptible to cold and more fearful of encountering it. By the mid 1930s his ‘sitting outdoors season’ didn’t usually start until quite late, mid-May. Some historical context is relevant here. The natural state of the eastern USA during the late 1920s and 30s was somewhat different than today, being often significantly hotter in summer and colder and more icy in winter. We can also assume that mistiness was often enhanced by household coal-fires being lit as the mornings and evenings grew chill. Domestic burning of ‘soft coal’ (heavy smoke) was then permitted, for instance, and only in 1946 did Providence begin to adopt clean-air measures. Add to that the likelihood of autumnal garden bonfires being lit.

Toward the end of his annual walking season he would have started to encounter such evocative mists, fogs and mizzling rains. Such mists were almost never captured by picture postcards, which makes scenes like the one seen above all the more valuable. They remind non-residents that New England was actually somewhat akin to England, in terms of the vagaries and mistiness of its very seasonal weather. The region wasn’t all an endless parade of bright summer-scenes.

Yet sometimes it was an endless parade of such scenes, or seemingly so when the bright clement weather would run on in the year. Such was the year 1933, for about six weeks from mid September to the end of October, and Lovecraft continued to enjoy such weather by taking cheap local bus-rides and walks. During most of October 1933 he even contrived to explore parts of the inland back-country far behind Providence. Here he is in October 1933, writing to Morton…

Well, well! The old man’s still out in the open! But though it’s quite oke for brisk walking, it ain’t so good for settin’ down and writin’. Hard work guiding the muscles of my pen hand, for I doubt if the thermometer is over sixty-eight degrees. Glorious autumnal scenery. I’ve spent the last week tramping over archaick rustick landskips, searching out areas still unspoil’d by modernity…

The run of fine weather was over by around Halloween. On 2nd-3rd November 1933 he wrote to R.E. Howard…

Our autumn has been very mild … But of course this is the very end of the season. No more continuous mild weather can be expected [now], though there may be isolated days of more or less pleasantness.

How did he first become sensitised to the Providence mists? He purposefully went walking in such conditions. In a 1933 letter to E. Hoffman Price he also recalled his youthful explorations of Providence, and how he had first become…

sensitive to the mystery-fraught streets and huddled roofs of the town, and often took rambles in unfamiliar sections for the sake of bizarre atmospheric and architectural effects ancient gables and chimneys under varied conditions of light and mist, etc.

He especially favoured such misty atmospherics when blended with a quality of “spectral hush & semi desertion”, ideally accompanied by far half-glimpsed vistas in which the imagination could lightly play. Hush was of course something rather more likely to be encountered at the very end of summer, when the region’s visitors and trippers had departed and the locals were again in a more workaday mood inside their schools and workshops. Lovecraft devised a proto-psychogeographic technique to greatly increase his chances of encountering such hushed moods. In 1933 he would alight from a local cross-country bus in the middle of nowhere, then strike across country in the hope of reaching another distant bus-route where he might flag down a homeward bus. Sometimes he was forced to hitch-hike back, though another part of his practice was to never actually ask for a free ride. Presumably this was partly because he feared that if he asked, a contribution to ‘gas money’ might then be demanded at the end of the journey? By such means he semi-randomly roved down back-roads and up little lanes that he had never seen before…

I have found several alluring regions never before visited by me [that] represent a settled, continuous life of three centuries suggesting the picturesque old world rather than the

strident new.

II. The cosmic mists.

In spring 1931 H.P. Lovecraft had the idea that rain clouds and drizzling mists might be partly influenced by fluxes in incoming cosmic-rays. Although he admitted that the confounding factors on earth would make such things difficult to measure and prove…

Just how far our precipitation is affected by the recent prevalence of ether-waves is a still-open question. The unprecedentedness of any natural phenomena is always subject to dispute — for certain types of phenomena may be naturally cyclic, whilst others may attract notice more than formerly because of increased reporting facilities [and newly populated areas growing up into] dense habitation” — Lovecraft in a letter to Clark Ashton Smith, 15th April 1931.

How prescient. Here his use of “ether-waves” does not mean broadcast radio, though that was by then a secondary shadow-meaning to be found in the radio trade press and a few newspapers. Lovecraft’s new-found ability to hear a speech by the British King may indeed have caused his eyes to mist up with tears of patriotic joy. But his knowledge of science was such that he would not have imagined that mass radio ownership might be the cause of mistier mornings on Rhode Island.

Lovecraft appears rather to have been using “ether-waves” as one finds it in standard 1930s textbooks of meteorological science. There it means radiant energy, such as cosmic-rays, x-rays etc. More specifically, a usage from the June/July 1931 Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society suggests that he had the cosmic-ray end of this spectrum in mind…

First, the cosmic rays enter the earth uniformly from all portions of the sky. Second, they consist – as they enter the earth’s atmosphere – of ether waves, not of electrons. (R.A. Millikan, the Bulletin quoting a talk of his given in September 1930.)

This use of “ether waves” then must indicate that Lovecraft was thinking in April 1931 of ether-waves (cosmic-rays) as inducing “nucleation” in the air, as a mechanism by which the cosmic forces that “filtered down from the stars” could affect the formation of clouds and mists on the earth. Thus, in his mind, a “recent prevalence of ether-waves” would affect “precipitation” in the weather on earth. His only apparent concern was “just how far” this effect carried through.

But all the scientific papers and textbooks say that this idea was first proposed in 1959 by Ney in his Nature paper “Cosmic radiation and weather”. Which implies that Lovecraft’s scientific intuition was thirty years ahead of the curve. Was Lovecraft then the first to propose a direct causal link between ‘space weather’ and ‘earth weather’?

The answer to this puzzle is probably that Lovecraft partly intuited the idea from the Nobel prize-winner Robert A. Millikan. We know this eminent and questing scientist was being tracked by Lovecraft, since he mentions Millikan to Frank Belknap Long in early 1929 when Lovecraft refers to a new theory… “Millikan’s “cosmic ray””… this being mentioned in the context of a discussion of “the radio-active breakdown of matter into energy, and the possible building up of matter from free energy” (Lovecraft).

This latter point indicates that Lovecraft knew that Millikan was proposing cosmic rays that were engaged in atomic construction rather than (as we now understand it) radioactive decay. This point may seem arcane today, but from such things the fate of the universe could be determined: construction meant a constantly-renewing universe, decay an eventual infinitely diffuse heat-death of the universe. The latter theory was given a substantial boost by the publication of the Big Bang theory which occurred in Nature on 9th May 1931 (after Lovecraft’s letter), this being apparently accompanied by much journalistic befuddling of a credulous public — with feverish talk of the coming “heat-death” of the universe.

Of course we cannot be certain that Lovecraft was reading Millikan directly, in the scientific journals available at his Public Library or in the periodicals room at Brown. Because Millikan might also have been encountered in the ‘popular science’ magazines and newspaper columns of the time. He was a popular figure, as scientists go…

Dr. Millikan was the first to prove [1925] the puzzling effect was actually the work of rays bombarding the earth from cosmic depths. The story of his [independent] search is one of the epics of science. Climbing mountain peaks in the Andes, sending aloft sounding balloons on the Texas plains, making tests in a raging blizzard among the Rockies, lowering lead-lined boxes of instruments into the water of snow-fed lakes in the Sierras, he followed one clue after another. (Popular Science, November 1936).

At this time the cutting-edge of science was headline news in regular newspapers, rather than being confined to specialist magazines or to slipshod hysteria in newspapers, as it mostly is today. We also known that Lovecraft was “strongly interested” in such things…

the absorption of radiant energy & re-emission at a lower wave-length has strongly interested me” — letter to Morton on fluorescent rocks, 13th November 1933.

… and that he later attended a public lecture on cosmic rays by W.F.G. Swann in early 1935 (Morton letters).

Perhaps this interest was strong enough in 1931 to cause him to follow the contents pages of the hard science journals, and to actually read papers by Millikan and others. Thus his reading of Millikan and a few others in early 1931 might plausibly be inferred. In which case Lovecraft most likely saw, or at the least read a good summary of, a key paper by Millikan titled “On the question of the constancy of the cosmic radiation and the relation of these rays to meteorology” (Physical Review, December 1930). Since this contains the following…

These rays must therefore exert a preponderating influence upon atmospheric electrical phenomena. [followed by a discussion of] “water vapour … condensing on ions” and the conclusion that… “the cosmic rays enter the atmosphere as ether waves or photons, and hence produce their maximum ionization, not at the surface of the atmosphere, but somewhat farther down.”

The paper does not appear to have been discussed or noted elsewhere. I have looked through and keyword-searched the book-length biography of Millikan (1982), and have searched Google Scholar and Google Books and a few other sources. Note that Millikan doesn’t actually baldly state the rays—>clouds idea in his paper, and he doesn’t actually mention precipitation (i.e.: rain-clouds, rain, drizzling mist). But he gives enough leads and hints in this paper that Lovecraft the meteorologist-and-astronomer would be able to tie the pieces together into a working theory. Given this absence of commentary elsewhere, I then have to suspect this paper is the source for Lovecraft’s April 1931 understanding of levels of precipitation being “affected by the recent prevalence of ether-waves”. The timing of the paper certainly fits neatly with that of Lovecraft’s letter to Smith. We also know that Lovecraft attended a lecture on the latest developments in cosmic rays, in early 1935. In a letter to Barlow he commented on this lecture, implying that he had already had a good working knowledge of such things and that the lecture had usefully updated this.

There is a further small puzzle here. How did Lovecraft know of the recent “prevalence” of ether-waves/cosmic-rays? Because these do not appear to have been measured in time-series until 1933. The answer to the puzzle might be that the aurora borealis was then recently known to be a natural proxy for incoming cosmic-rays. An increase in the aurora would have been noted in the meteorological and polar journals, possibly even in the newspapers. The effect on shortwave radio-reception may also have been understood to be an indicator. We know that Lovecraft enjoyed ‘fishing’ on his older aunt’s radio-set for the most distant exotic radio stations he could find, and this could have sometimes meant rare distant shortwave signals bouncing off the ionosphere. His younger aunt’s radio set was apparently not so powerful. Yet regular ‘fishing’ on either might still have led him to build up a mental time-series of the disturbances in the upper-atmosphere.

“I sometimes ‘fish’ for distant stations when over there — for there is a fascination in the uncanny bridging of space” (Lovecraft in October 1932).

What then was his idea of this rays-to-clouds effect, put in modern scientific terms? At its crudest the idea of “nucleation” holds that: 1) cosmic-rays arrive and cause ionisation inside our atmosphere; 2) which introduces more tiny floating nuclei suitable for water-droplets to form on; 3) and in that way certain types of low-level cloud are more likely to arise when there are more rays. The science of this is still being actively researched, at least by those willing to brave the venomous politics of the field. Personally I remain to be convinced by scientists who suggest more sophisticated and roundabout ideas about how cosmic-ray fluxes and clouds might interact (and thus influence weather). Yet it’s not wholly impossible that Lovecraft’s 1931 hypothesis about ‘cosmic mists’ might one day be agreed to be correct, if science can see through the fog of confounding factors.

Pingback: HPLinks #29 – Schultz, Pera, ‘We Are Providence’ stage play, Faunus in PDF, a pagan thesis, antique monsters, clouds and more… | Tentaclii