Here’s a calming electronic-orchestral neo-romantic album which some readers may care to explore in the hectic run-up to Christmas and the New Year, London Overgrown by John Foxx (2015, 52 mins). It’s one of his best ambients, and is free in full and ad-free via an ordered YouTube playlist.

Foxx is solo and purely instrumental here and he revisits the mood — though not the rapid electro-pulses and singing — of his early classic post-Ultravox album The Garden. Those who know Eno’s best ambient and the instrumentals on early albums — such as Before and After Science and Another Green World — may hear small homages and nods to the master on several tracks in the first half of the album. In the second half it becomes even more eerily becalmed and frankly almost dull in places, but in a rather British ‘sublimely beautifully decay’ way. The album has a rather downbeat trailing-off ending, and some listeners may like to segway the final track into something similar but a bit more upbeat from Foxx, perhaps suggesting a return or awakening from dreamland wanderings.

* Foxx’s sleevenotes for London Overgrown.

* Some booklet pictures for London Overgrown.

* My anthology London Reimagined: an anthology of visions of the future city, which you may care to dip into while listening.

* Amazon download for London Overgrown, with better quality audio than on YouTube.

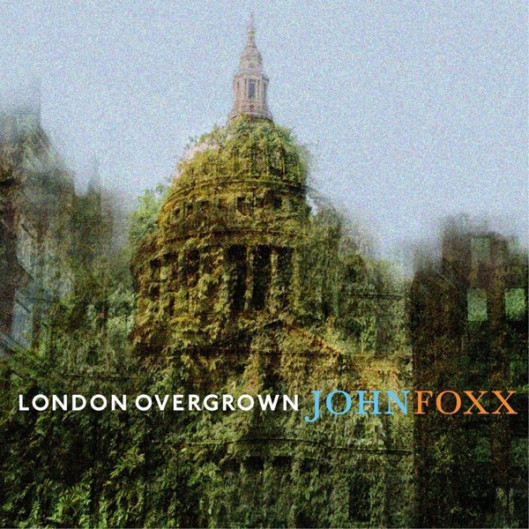

The album’s cover suggest the post-apocalyptic, something I’m not a great fan of. Though this isn’t part of the tiresomely relentless wave of post-apocalyptic science-fiction. In which an old-school genre wild west story gets retooled with a thin sci-fi veneer, punky haircuts and some sub-Riddley Walker slang, and an uber-violent gang of Bad Men who menace a peaceful enclave of tofu-knitting eco-hippies. Similarly I have little time for the escapist neo-primitivist future-fantasies of ‘total re-wilding’, to be found among both the anarchist eco-left and in certain theoretical grouplets of the continental far-right, and which sometimes also feed into science-fiction.

But in the case of Foxx’s London Overgrown album we have something different, I think, and with different intellectual roots. His is a poetic idea of wandering, walking in an abandoned and partially overgrown empty city, taking in the sublime sunset vistas and pondering the garden-clad architecture of a lost civilisation. Psychogeography, if you like, but without the tired old leftist politics it’s often been freighted with by the London school.

Such exploration was of course a theme that Lovecraft explored in both his night-walks and his fiction, and he did so on the back of the many very real archaeological discoveries of ruined cities in the 1870s-1930s — think, for instance, of his Nameless City, Mountains of Madness, Kadath, and other works. Lovecraft would have made a fine pith-helmeted archaeological explorer, I think, had his constitution been more robust. He would have revelled in the heat involved in somewhere like Mexico, then the ‘hot ticket’ to career success for Americans such as his friend Barlow. Still, at least he paced the ancient cities in his imagination and dreams, to our great benefit.

Thus, though Foxx’s album cover montage of St. Paul’s dome implies that the album is a projection into ‘a future ruined’, it seems to me more of a nostalgic recovery in music of a Richard Jefferies (Wild England) / H.G. Wells (Time Machine) vision of an overgrown London. Foxx’s album arises from the poetic response to the real ruined cities that were encountered in the days of Empire. In which explorers entered the silent empty ruins of great cities unseen for great ages, and there pondered and wove poetry on the inevitable fading away of all Empires. As such the album seems an echo of a real lived moment in cultural time, rather than a future-fantasy.

As Foxx states in his sleeve-notes, his music also evokes another more recent reality — the way he’s lived through something comparable, namely the 1974-2014 de-industrialisation and restoration of those parts of our English landscapes that had been made primarily by the industries of steel, coal, and heavy manufacturing. Restoration sometimes by heroic but unsung human reclamation works, sometimes by natural over-growing aided by the carbon-fertilisation effect, often a bit of both. Again, this has been a lived reality, as cities such as Stoke-on-Trent — once the most polluted in Europe — really have changed over 40 years from industrial wasteland to relative verdancy. And done so at such a slow pace that the mental preconceptions of their car-driving residents (who usually only see the place from a few routinely-travelled grotty main roads) have yet to catch up with the changed realities and newly verdant terrains which lie behind the houses and the tawdry store-fronts. To coin a psychogeographic phrase: “Behind the storefront, the forest!”