Book Review:

David Goudsward, H.P. Lovecraft in the Merrimack Valley, Hippocampus Press, summer 2013. $15 print-on-demand paperback, 192 pages. Foreword by Kenneth W. Faig. Jr., with an afterword by Chris Perridas. Illustrated, basic index. The book was read completely and carefully.

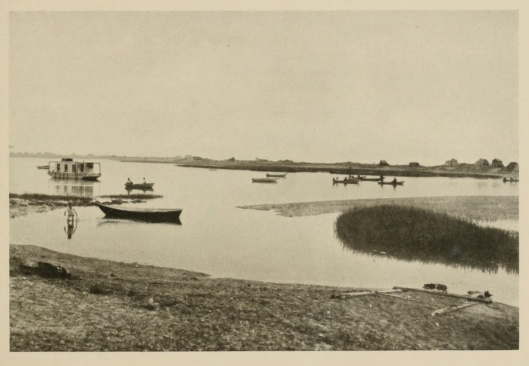

David Goudsward is obviously a prodigious walker, just as H.P. Lovecraft was. One has to marvel at the amount of physical legwork and boot leather that went to make this new book. Goudsward has walked and ridden every one of the various routes that Lovecraft threaded through the Merrimack Valley, and he has also wandered through what remains of the antiquated foot-ways of its eastern fishing towns. At the end of the book he even provides readers with a useful short gazetteer, listing places he has visited and which are currently open to the public. For those who can’t make such visits the book offers abundant and crisply reproduced black-and-white pictures. These pictures are either Goudsward’s own, or those he has ably sourced from local archives.

The book is well organised, and the text and pictures flow well together. But much tedious and time-consuming page-flipping might have been avoided by having the footnotes placed at the bottom of each page, instead of at the back of the book. It would also have been useful to have had at least one map of the area, but there are none. This seems a pity, when there are excellent old maps in the public domain at high resolution…

Above: Newburyport in 1888, topographic map. Full version.

Above: Newburyport in 1888, topographic map. Full version.

Of course the more digitally adept reader might juggle a digital tablet with the book, and thus ‘follow along’ via the wonderful Google Maps and Google Street View (a free tool which now allows researchers to scout out Lovecraft’s locations from the comfort of their PC). Sadly the modern Haverhill — the setting for the first half of this book — doesn’t lend itself to such Googly goodness: Goudsward informs the reader that the centre of Haverhill was effectively destroyed by the urban-planning vandals of the 1960s and 70s.

Above: Haverhill in 1888, topographic map.

Above: Haverhill in 1888, topographic map.

The book opens with a short but engaging foreword by the veteran Lovecraft researcher Kenneth W. Faig, Jr. Faig immediately grabs the Lovecraftian reader by the lapels, with a stirring call to undertake the daunting task of making a complete day-by-day summary time-line of Lovecraft’s life, in the same manner as has already been done for Abraham Lincoln. That might best be done alongside an online searchable edition of the complete corpus of surviving letters (with only fragments shown, as with Google Books, in order to prevent piracy). In the meantime, books such as H.P. Lovecraft in the Merrimack Valley can help to fill some of the gaps, in terms of an almost day-to-day documentation of Lovecraft in one particular place.

Goudsward more or less strides through the events chronologically, with only a few sharp switchbacks into town histories. He opens with a succinct but detailed account of the life of Lovecraft’s fellow amateur pressman Charles W. “Tryout” Smith (1852-1948) of Haverhill. In the book’s appendices “Tryout”, along with Myrta Alice Little, is treated to a fine and painstaking listing of all solo publications.

Then the reader is stepped through the story of Lovecraft’s initial 1921 stay-over meeting with a near neighbour of “Tryout”. This person was the very tall, very beautiful and very intelligent Myrta Alice Little (1888-1967). Lovecraft was perhaps not ‘on top form’ when he met her, being only a few weeks into mourning for his dead mother. Myrta fairly soon decided to marry a local Methodist preacher, and Lovecraft was rather left in the dust. I was surprised to discover that “Tryout” Smith also swiftly departed the Haverhill scene, albeit in a very different way — he became a total recluse at a place called Plaistow between 1922 and 1926, seemingly admitting no visitors at all. Not even Lovecraft.

But Lovecraft did retain a good reason to visit Haverhill, and to explore the area’s antiquities. From March 1922 he had cultivated a friendship with a bright thirteen year old boy named Edgar J. Davis (1908-1949) of Haverhill. Lovecraft befriended Edgar’s family and was allowed to stay over at his home. Together he and Edgar were allowed to go off on trips of local exploration. They eagerly visited the shadowy crumbling estuary-mouth seaport of Newburyport, later admitted by Lovecraft to be — in part — a model for the famous story “The Shadow over Innsmouth” (written Nov-Dec 1931). Here one of Goudsward’s claims about Newburyport made me pause. It was a small claim that the old Bayley Hat (Chase Shawmut) factory was the direct model for the Marsh Refinery of “Shadow Over Innsmouth” (p.47). I felt this claim needed more evidence. On the other hand, the place does look like a plausible candidate, seen here in an elevation sketch I found from circa 1903…

Like many of Lovecraft’s places, Innsmouth was very probably a bit of a literary collage. He probably borrowed elements from different places: a marshy shoreline from here; a familiar town grid plan from there; add a road by which to approach in an atmospheric manner; give it human pathos by using the crumbling elegant architecture and fishing shacks of Newburyport. Then top it off with a creepy reef way offshore; a horrible hotel; a mysterious refinery; and an old abandoned railroad, some of which were perhaps simply dreamed up from his abundant imagination to suit the needs of the plot.

Goudsward’s book also looks at Lovecraft’s later (post New York) trips to Newburyport and the region, in the company of W. Paul Cook. The bright young Edgar J. Davis had by that time grown up and gone off to Harvard to study law. In this section I again paused over just one of the claims made: that a coral reef Lovecraft saw on a Miami tourist trip was the direct inspiration for Innsmouth’s Devil Reef (p.70). Yet Lovecraft’s description of the jaunt (not given in the book) seems rather incongruously bright-and-sparkly for something so dark and brooding…

“… sailed out [from Miami] over a neighbouring coral reef in a glass-bottomed boat which allowed one to see the picturesque tropical marine fauna & flora of the ocean floor.” (Selected Letters III, p.380)

The northern third of the nearby ‘Isles of Shoals’, four miles offshore from nearby Portsmouth and ten miles NW of Newburyport, might have been a more plausible suggestion for the idea of the Reef. Although that’s not to say that Lovecraft ever visited any of the bleaker of those islands. While a couple of the larger islands had become minor tourist traps (Hawthorne wrote the junior HPL fave Tanglewood Tales there), most of ‘The Isles of Shoals’ is a sprawl of lonely low islands and tidal ledges just above the sea, where “ragged reefs run out beneath the water in all directions” (Among the Isles of Shoals, 1873). Lovecraft had visited Portsmouth just one month before writing “The Shadow over Innsmouth”.

Above: ‘The Isles of Shoals’ seen in relation to Portsmouth, 1917 topographic map.

Above: ‘The Isles of Shoals’ seen in relation to Portsmouth, 1917 topographic map.

I did wonder if more might have been said in the book about the historical as well as the geographical context. By historical context I mean the sweep and impact of large implacable forces, such as the shifts in the economy and the coming of modernity to the area in the 1920s. Goudsward does have some short town histories, and some paragraphs that try to say why Newburyport was decaying. But his bibliography lacks the sort of books that might have given him some useful big spotlights, with which to illuminate small details to do with Lovecraft. While pounding the same streets as Lovecraft did can obviously be very useful, an equal pounding on digital doors — of Google Books, HathiTrust, Archive.org, Library of Congress pre-1922 online newspapers, and suchlike — might have yielded Goudsward a few useful additions to his book. For instance, the drastic overfishing at Innsmouth and the town’s keen desire for vast new shoals of fish. Is something similar to be found in the history of the Merrimack River? At Google Books I swiftly found the interesting fact that…

“Fish were a critical link in the Merrimack valley’s food chain”, and that these fish were vastly overfished and the river over-dammed by commercial interests in the early 1800s, and the fish life of the river consequently suffered a severe ecological collapse in what had once been one of the finest salmon rivers in America. (For full details on this story see the chapter “Depleted Waters” in Nature Incorporated: Industrialization and the Waters of New England, Cambridge University Press, 2004.)

There seems an obvious parallel here with the depiction of the fictional collapse of the Innsmouth fishing economy…

“Most of the folks araound the taown took the hard times kind o’ sheep-like an’ resigned, but they was in bad shape because the fishin’ was peterin’ aout…” (Zadok in “Shadow over Innsmouth”)

“That fishing paid less and less as the price of the commodity fell and large-scale corporations offered competition… [but by then Innsmouth had the fish being herded in…]” (“Shadow over Innsmouth”)

I also wondered about a rhetoric around population ‘degeneration’ at the time, apparently specific to the region. I wondered how early this developed in 1921—1931, the period under discussion in the book, as evidenced by the local and regional newspapers…

“by the 1930s […] entire regions like north-eastern Connecticut and the Merrimack Valley of New Hampshire and Massachusetts appeared to be left behind by history, and the sight of abandoned factories was as common as that of deserted farms” […] “the rural hinterlands seemed to be largely populated with inbred, degenerated retards” [and newspapers pictured] “them as a bunch of mutated dwarfs, giants, and idiots.” (Bernd Steiner, “The Decline of a Region”, H.P. Lovecraft and the Literature of the Fantastic, 2007, p.33).

Finally, there is ‘Mystery Hill’. Goudsward has long been associated with the so-called megalithic site of ‘Mystery Hill’ in New England, and so I was rather dreading reading a gusher of an essay on the topic, but find that the essay is relegated to an appendix in the book. I am no expert on the New England megaliths controversy, other than to know to be highly sceptical of North America’s ubiquitous faux prehistory. But I was pleased to find what appears to be a restrained and rather careful look at the known evidence about Lovecraft having once visited this site. I only worried that I could find nary a whit nor a sniff of the name “Pattee’s Caves” (which Goudsward states was the old local name for ‘Mystery Hill’, before its mid 1930s purchase and transformation) in any of the big pre-1926 online archives. After sifting the dubious claims of Munn and others, Goudsward finally alights on an elegant and moderately plausible way to get Lovecraft up to ‘Mystery Hill’. I won’t spoil the surprise for readers, but it’s a fun ride getting there. Even if Goudsward is right on that point, then it still doesn’t prove that the highly dubious man-sized stone slab now in pride of place at ‘Mystery Hill’ was present and visible there in 1921. Nor that Lovecraft then recalled that same slab a few years later, and fictionally hoisted it atop Sentinel Hill in “The Dunwich Horror”.

Overall the book is an engaging read, and I recommend it to those who want the fine and thought-provoking details about the inspirations for Innsmouth and how Lovecraft came to know the Merrimack River area.

Contents:

Foreword, by Kenneth W. Faig, Jr.

Preface

Acknowledgements

H.P. Lovecraft in the Merrimack Valley

Transformations

First Visits: 1921

Whittierland and Newburyport

Intermezzo: 1924–1926

Innsmouth Ascendant: 1927–1931

Dreams and Eclipses: 1932–33

Shadows out of Haverhill: 1934–36

Coda

Appendices

The Haverhill Convention, by H.P. Lovecraft

First Impressions of Newburyport, by H.P. Lovecraft

Tryout’s Return to Haverhill

Plaistow, N.H., by C.W. Smith

The Return, by H.P. Lovecraft

The Published Works of Myrta Alice Little Davies

Howard Prescott Lovecraft, by C.W. Smith

The Publications of Charles W. Smith

H.P. Lovecraft, “The Dunwich Horror,” and Mystery Hill

Sites Open to the Public

Notes

Lovecraft: A Sense of Place and High Strangeness, by Chris Perridas

Bibliography

Index