“Kuranes came very suddenly upon his old world of childhood. He had been dreaming of the house where he was born; the great stone house covered with ivy, where thirteen generations of his ancestors had lived” (“Celephaïs”)

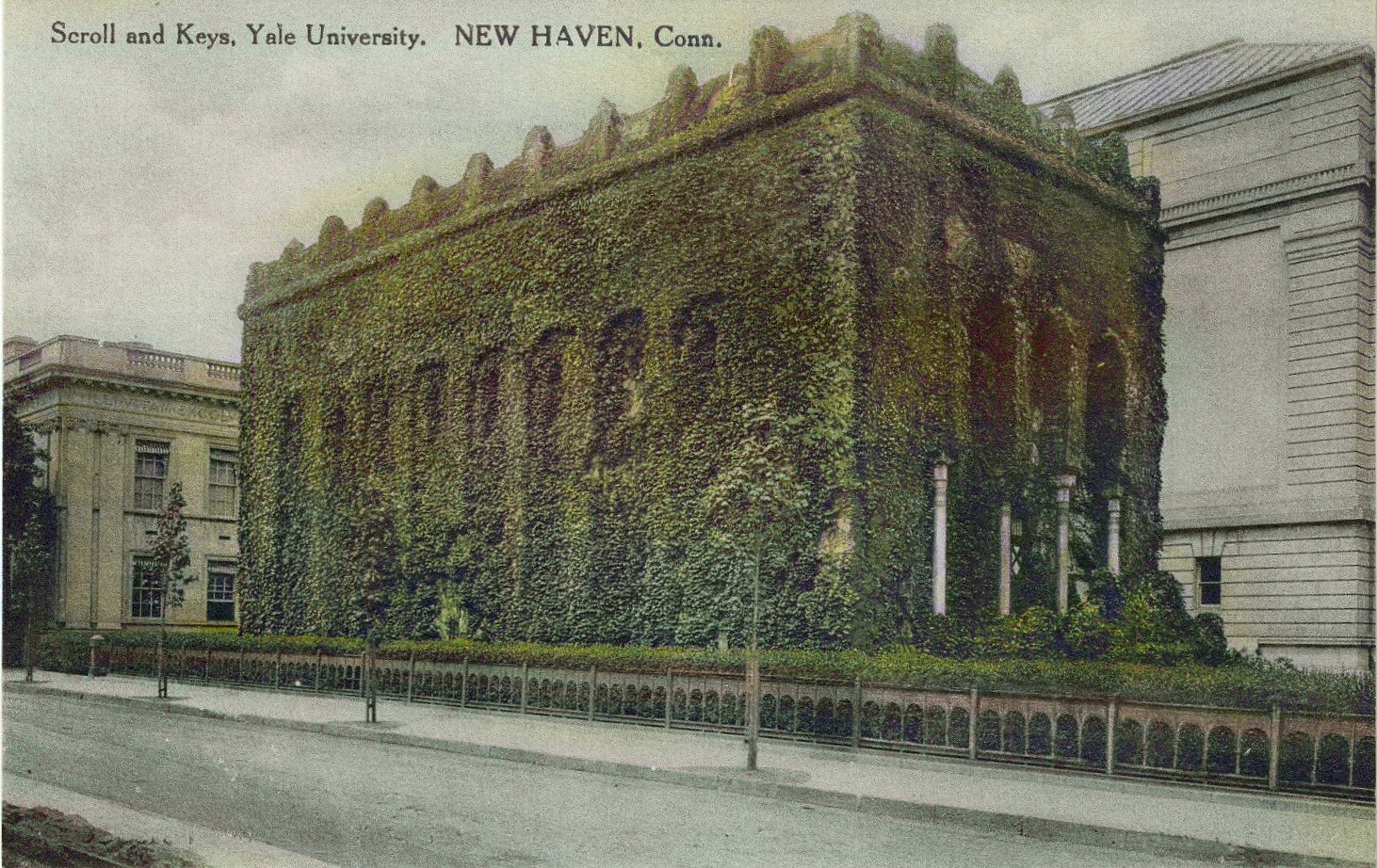

The buildings Lovecraft strolled past and visited were often substantially covered in greenery, usually ivy, often to an extent that seems incredible today. Such as this…

Tolkien also lived in the same sort of environment, with the venerable Country Life magazine going so far as to chide his College for their “excessive” love of greenery, at a time when such greenery was everywhere rampant in England.

The bareness of brick often seen today is a legacy of the post-war ‘ivy removal’ fad, which by the 1960s and 70s had run as rampant as the ivy it condemned. Ivy removals worked alongside the fetish of the average modernist for bare everything, including brickwork and concrete. And perhaps alongside the interests of modernism-demented city authorities, with their passion for the sight of any visible decay which might justify demolishing swathes of old buildings. The economic depressions of the 1970s probably didn’t help — easier to tear the ivy down, than pay a man to trim it back every two years.

Yet it now turns out that ivy removal was the result of a false consensus, one with no basis in either building science or home economics. I was interested to learn of a recent major UK study by the Royal Horticultural Society and the University of Reading. An ivy covering reduces surface temperature swings on new brickwork, thus preventing flaking and cracking from developing over time. Damp was not ‘trapped’, as was commonly said by the ivy-haters, and the humidity was actually stabilised by the ivy covering and rain was kept off. Again, this stability helps to preserve the brick surface. Frost, salts, and vehicle pollution are all protected against, far outweighing any micro-damage done by the tiny adhesion points of the climbing ivy stems.

There appears to be a big energy benefit. The study found indoor summer temperatures cooler by up to 7.2 degrees. Given the UK’s usual dismal summer temperatures, this may not actually be a good thing, and might involve the inhabitants donning pullovers and hats. But the finding may interest places such as Lovecraft’s Providence, which endure much more steamy summers. Less air conditioning would be needed. The test houses also lost less heat in winter (costing less to heat, by as much as 20%), which would have been of much more use in the British climate.

That saving would of course have to be weighed against the cost of trimming back the ivy every two years. But likely the house owner could come out on top financially, especially given the soaring cost of energy. Also, I wonder if some sort of ivy-trimming flying drone might not yet be invented, with an AI camera to detect young and easily cut-able shoots? Consider also the ivy’s likely deterrence of the sort of graffiti scrawls which devalue one’s house, and also the entire street, through deterring possible house buyers.

The new UK study confirms earlier work which asked “Is Ivy Good or Bad for Historic Walls?”. Another recent study in Toronto suggested the easy-grow big-leafed Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata) as the ideal for restoring cities on the East Coast of the USA and Canada.

“… the ivy was climbing slowly over the restored walls as it had climbed so many centuries ago, and how the peasants blessed him for bringing back the old days” (“The Moon-Bog”).

And perhaps not only restoring. Those who laugh at the Syd Mead-like visions of a ‘solarpunk’ future, pointing to the unlikely abundance of greenery hanging from the gleaming white buildings, perhaps overlook both the likely advances in materials bio-science (building materials ‘grown’ from fungi) and in the tools (drones and robots) needed to control vegetation. Possibly also an advanced form of drip-feed irrigation. Future white-walled towns built from fungi and clad with gothic ivy, perhaps. Lovecraft would surely approve of that.

Ivy is rarely a notable feature of Lovecraft’s work, other than the two instances above where it is linked with an ancestral home. Since such greenery was at that time a commonplace which was all around him. As he states in Dexter Ward, speaking of this lack of interest in what one knows and sees everyday…

The odd thing was that Ward seemed no longer interested in the antiquities he knew so well. He had, it appears, lost his regard for them through sheer familiarity; and all his final efforts were obviously bent toward mastering those common facts of the modern world

He did make one early venture into plant horror, “The Tree”, but that was not a very successful tale.

But his protege Belknap Long, an inhabitant of the largely greenery-starved New York City, would create a wartime series for boys featuring monster plants (John Carstairs). For a high-rise apartment dweller such as Long, plants were a more unusual thing, and thus might be monster-ized following the lead given by various earlier pulp tales.

There are however some instances in Lovecraft’s letters, such as this from 1923 in which an ivy clad house elides with brief horror…

The coach ride [to the old Salem-Village] was delightful, giving frequent glimpses of ancient houses in a fashion to stimulate the antiquarian soul. Suddenly, at a graceful and shady village corner which the coach was about to turn, I beheld the tall chimneys and ivy’d walls of a splendid brick house of later Colonial design [… Asking to alight from the coach, and going around the back of the house] I loudly sounded the knocker […] My summons was answer’d simultaneously by two of the most pitiful and decrepit-looking persons imaginable — hideous old women more sinister than the witches of 1692, and certainly not under 80. For a moment I believ’d them to be Salem witches in truth…