As we move into the New Year, it seems apt to take a look at the annual almanacs which H.P. Lovecraft cherished. Not quite postcards, of course, but still pictorial.

He inherited, and then further developed, a substantial collection of such old country almanacs. He writes in a letter that this family collection, when first passed down to him…

went back solidly only to 1877, with scattering copies back to 1815

Trying to complete this set eventually became a keen occasional hobby, though he had some luck there. He was allowed to root among the home storage attic of his sometime-friend Eddy’s book-selling uncle, and he descended the ladder with many a rare old copy. Which Uncle Eddy then sold him at a very affordable price. This haul appears to have spurred his ambitions, and he wrote…

I am now trying to complete my family file of the Old Farmer’s Almanack

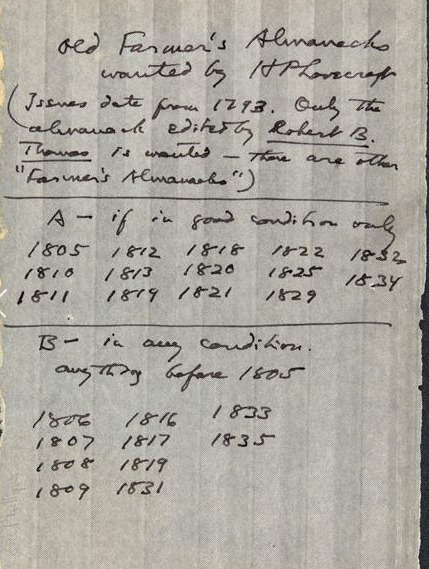

Here we see Lovecraft’s collecting ‘wants list’, as he tried to complete the set…

What, exactly, was this publication? Archive.org now has a small selection of scans of this Old Farmer’s Almanack, and thus we can get a better idea of what Lovecraft found between the pages. To be specific, he inherited and collected old copies of the Old Farmer’s Almanack edited by Robert B. Thomas. (It can’t be linked, as the URL is malformed, but if you paste this into the Archive.org search-box you should get it: creator:”Thomas, Robert Bailey, 1766-1846″ )

There were other publications of the same or similar title, but Old Farmer’s Almanack was Lovecraft’s mainstay. Which is not say he wasn’t delighted to discover that other similar almanacs were still publishing, out in the countryside…

It sure did give me a kick to find Dudley Leavitt’s Farmer’s Almanack [Leavitt’s Farmer’s Almanack, improved] still going after all these years. The last previous copy I had seen was of the Civil War period. But of course my main standby is Robt. B. Thomas’s [Almanack]

Thomas’s Old Farmer’s Almanack had begun publication in 1793. As we can see from the above list, Lovecraft was especially keen to get hold of anything before 1805 and in any condition. Many of these used the old long-S in the text…

I can dream a whole cycle of colonial life from merely gazing on a tattered old book or almanack with the long S.

This dream had first occurred very early in his life, and at age five the family Almanack had made a lasting impression…

my earliest memories — a picture, a library table, an 1895 Farmer’s Almanack, a small music-box

Evidently then this annual was taken and consulted in his home at that time. Also cherished and kept, since we know he was able to read the entire set…

[As a boy] I read them all through from 1815 to the present, & came early to think of every turn & season of the year in terms of the crops, the zodiac, the moon, the ploughing & [harvest] reaping, the face of the landscape, & all the other primeval guideposts which have been familiar to mankind since the first accidental discovery of agriculture in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley.

Nor did he overlook the rustic pictures…

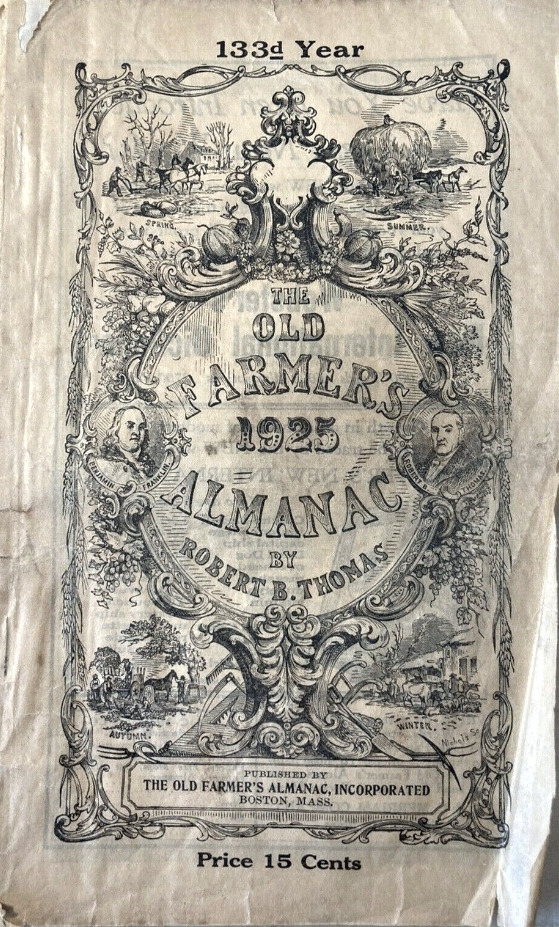

I am always fond of seasonal pictures, & dote on the little ovals on the cover of the ancient Farmer’s Almanack — spring , summer, autumn, & winter

On his travels he later found places where the homely traditions and moon and star-lore of the Farmer’s Almanack were still followed, such places as Vermont…

That Arcadian world which we see faintly reflected in the Farmer’s Almanack is here a vital & vivid actuality [in rural Vermont]

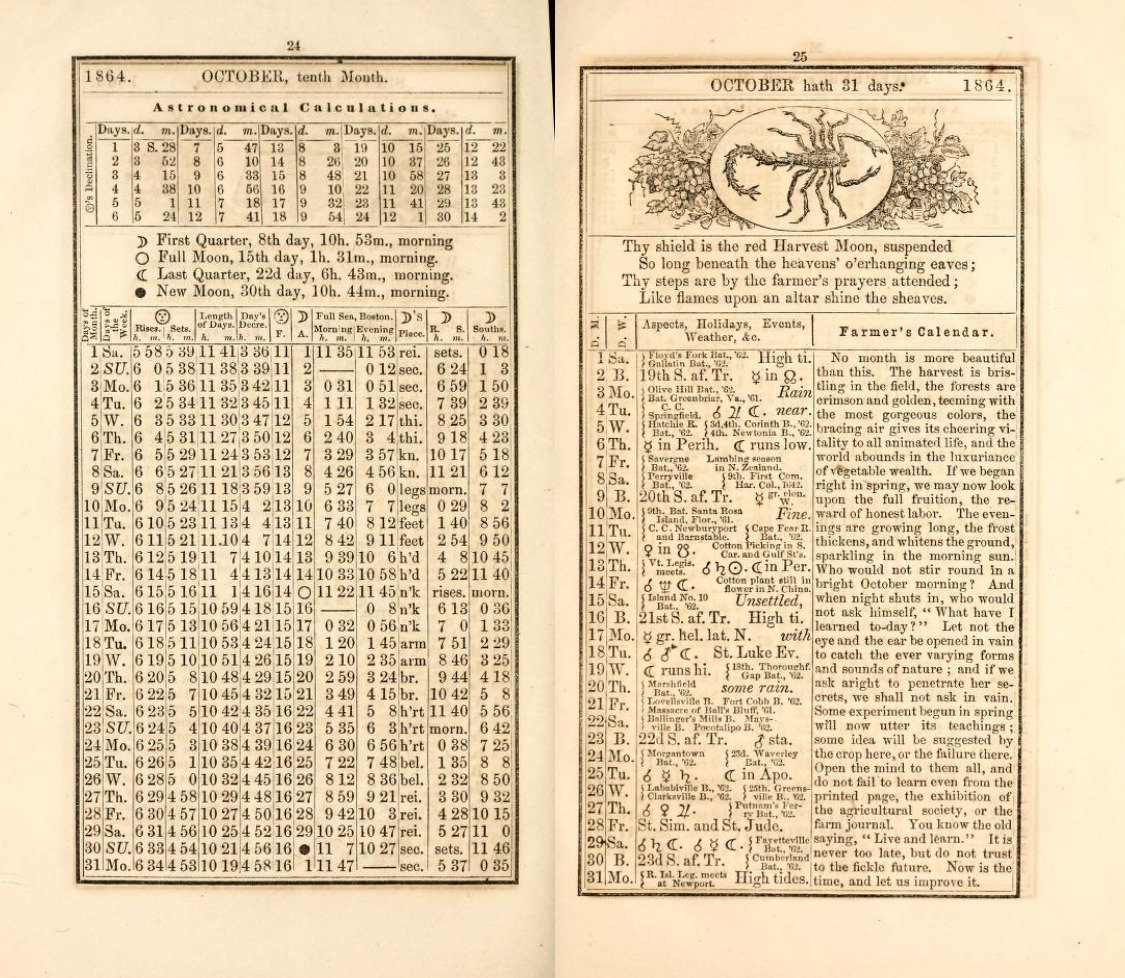

The publication was indeed a useful one. For instance it enabled Lovecraft to anticipate with ease the year’s lesser heavenly events…

Sun crosses the equinox next Wednesday at 7:24 p.m. according to the Old Farmer’s Almanack — which we have had in our family, I fancy, ever since its founding in 1793.

Having sent some introductory astronomy books, Lovecraft also sent young Rimel a copy of the latest Old Farmer’s Almanac for the coming year of 1935. In a later letter to Rimel of 28th January 1935, Lovecraft explicitly recommends the publication for astronomy use. The Almanac being…

capable of assisting the study of astronomy quite a bit.

The weather predictions found in its pages were perhaps of less use. Or at least, they had become so by the late 1970s. In 1981 Weatherwise magazine made a tally of sixty forecasts across five years. They found the month-by-month Almanack forecast to be little better than chance by then. How accurate the monthly weather forecasts might have been in the 1895-1935 period and in Providence remains to be determined. It might be quite interesting to tally that, with perhaps a leeway of two days. But to do so one would likely need to go back to the original journal / newspaper summaries of the month’s actual weather, rather than trust any recently ‘rectified’ computer-created data for those decades.

The Almanacks also contained a wealth of rather more reliable factual information. Such as the dates of the year’s key elections, court days, festival and saint’s days, tides, recurring natural events (usual time of lambing, bringing in cows for the winter etc), anniversary dates for sundry historical events, lists of Presidents, the standard weights and measures, distances, nutritional values of various crops and fodder, together with small amusements such as riddles and poetry. Short articles could also be present. Most importantly for Lovecraft’s huge flow of parcels and letters, the little booklets also appear to have given the latest postal regulations in a concise form.

In format they were rather like Lovecraft’s stories, then. A whole lot of sound facts garnished with a few slivers of delicious speculation (meaning the weather forecasts, rather than monsters and cults). Indeed, one might see something of the ‘carnivalesque’ at work in such publications. The use of a small inversion, that by its amusing ridiculousness serves to bolster the belief in the facticity of the rest of the structure.

The latest annual Almanack was also ever-present in Lovecraft’s own study, as he wrote to Galpin in 1933…

You may be assur’d, that my colonial study mantel has swinging from it the undying Farmer’s Almanack of Robert B. Thomas (now in its 141st year) which has swung beside the kindred mantels of all my New-England forbears for near a century & a half: that almanack without which my grandfather wou’d never permit himself to be, & of which a family file extending unbrokenly back to 1836 & scatteringly to 1805 still reposes in the lower drawer of my library table [evidently Lovecraft had by this time added 1876-1836 to the “family file”] … which was likewise my grandfather’s library table. A real civilisation, Sir, can never depart far from the state of a people’s rootedness in the soil, & their adherence to the landskip & phaenomena & methods which from a primitive antiquity shap’d them to their particular set of manners & institutions & perspectives.

This mantel-hanging had been a long-standing practice. For instance it was noted by his earliest visitor, when Lovecraft was emerging from his hermit phase. Rheinhart Kleiner recalled of his curious visit to the darkened room that…

An almanac hung against the wall directly over his desk, and I think he said it was the Farmers’ Almanac.

Lovecraft even kept up the tradition during the hectic New York years, writing in late 1924…

the Old Farmer’s Almanack … of which I am monstrous eager to get the 1925 issue

In that era the Almanacks were very often personalised and annotated quite heavily by their users, and a rural man’s personal collection grew to form a sort of natural diary and personal time-series for useful farm data. In 1900 40% of the American people still worked on the land, so such things were vital.

So far as I’m aware we have none of Lovecraft’s own copies today, so we don’t know if he also marked and noted them in various ways. Or if he had inherited copies that had been so marked by his relatives.

He also hints at being aware of and valuing another such publication. For instance, when he remarked on the discovery of the planet Pluto he wrote…

the discovery of the new trans-Neptunian planet …. I have always wished I could live to see such a thing come to light — & here it is! …. One wonders what it is like, & what dim-litten fungi may sprout coldly on its frozen surface! I think I shall suggest its being named Yuggoth! …. I shall await its ephemerides & elements with interest. Probably it will receive a symbol & be treated of in the Nautical Almanack — I wonder whether it will get into the popular almanacks as well?

In his early newspaper columns on astronomy he also appears to refer to this same publication…

The motions of these satellites, their eclipses, occultations, and transits, form a pleasing picture of celestial activity to the diligent astronomer; and are predicted with great accuracy in the National Almanack. [I assume here a mis-transcription by the newspaper editor of “National” for “Nautical”, or perhaps a correction to its shorthand name in the district].

Indeed, both Almanacks feature in Lovecraft’s “Principal Astronomical Work” list, among the vital accessories needed for a study of the night-sky…

Accessories:

Lunar Map by Wright.

Year Book — Farmer’s Almanack.

Planispheres — Whitaker & Barrett-Serviss.

Atlas by Upton — Library.

Opera glasses — Prism Binoculars.

Am. Exh. & Want Almanac. [meaning the American Ephemeris & Nautical Almanac, as “Exh.” is “Eph.” and “Want” should be “Naut”]

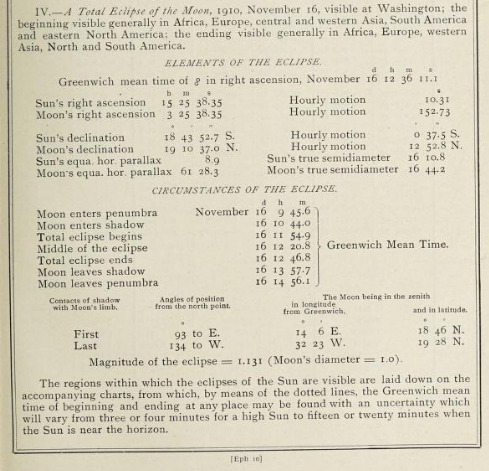

This Nautical Almanac is also on Archive.org, so we can peep inside a copy of that from 1910. Forthcoming eclipses were noted over several pages. Here, for instance we see all the details needed to observe a total eclipse of the Moon in November 1910, the beginning visible from “eastern North America”. I think we have a hint here about what Lovecraft was likely to have been doing in the late evening of 16th November 1910…

Archive.org also has The Old Farmer and his Almanack, a 1920 book which surveyed the topic with erudition. Lovecraft was heartily pleased to discover and read it shortly after publication.

Almanacks occur only once (and very trivially) in Lovecraft’s poetry. The one use in his fiction is more intriguing. In “The Picture in the House” (December 1920) a book is noted…

a Pilgrim’s Progress of like period, illustrated with grotesque woodcuts and printed by the almanack-maker Isaiah Thomas

The sharp-eyed will have spotted that Lovecraft might have meant to imply that this “Thomas” could have been the ancestor of the Robert B. Thomas of Old Farmer’s Almanack fame. That might be how some savvy bookmen took it at the time, but it is not so. For Lovecraft would have known that there was a real “almanack-maker Isaiah Thomas” and that he was no relation. Robert B. Thomas himself tells us this fact, in recalling his early years of trying to get a start in publishing almanacks…

I wanted practical knowledge of the calculations of an Almanack. In September, I journeyed into Vermont to see the then-famous Dr. S. Sternes, who for many years calculated Isaiah Thomas’s Almanack, but failed to see him. … In the fall, I called on Isaiah Thomas of Worcester (no relation) to purchase 100 of his Almanacks in sheets, but he refused to let me have them. I was mortified and came home with a determination to have an Almanack of my own.

Thus my feeling is that Lovecraft knew of these snubs and also, probably while reading his The Old Farmer and his Almanack (1920), had learned that Isaiah Thomas had sustained a sideline in publishing booklets containing the worst sorts of “astrology, palmistry, and physiognomy”. Thus, later that same year Lovecraft gave curmudgeonly old Isaiah Thomas a small poke in his fiction, by implying that Isaiah had marred a classic book with “grotesque” pictures — so “grotesque” that the resulting book ended up resting next to Pigafetta’s account of the Congo and its cannibals.

Update: The Nautical Almanac. Hathi now have the full run of the Nautical Almanac online.

An excellent account of a rather neglected interest of Lovecraft. I might add that, until 20 years ago, no astronomical observatory would be without the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac or its equivalent. Many was the time I used its information to set the telescope coordinates for a night of observing. Now, of course, data files provide the same information and there is no need for a physical copy of that volume.