Edward Lloyd Sechrist (1873-1953) was born in 15th August 1873 in Wayne County, Ohio. He was notable for being one of the world’s leading scientific bee-keepers and an important writer on bees, from about 1922 onward, and he contributed much to the developing art and science of modern beekeeping. He corresponded with H.P. Lovecraft in the 1920s and became his good friend.

Early Life:

Sechrist was born and raised on SpringCrest Farm, the Sechrist family farm located near Pleasant Home in Wayne County, Ohio. There is A History of the Sechrist Family (1919), written by Julia Ann Shoemaker Sechrist (1846-1935) of that branch of the family, and although this is not online it presumably has full details of their background.

Sechrist sitting (middle) with his parents.

Sechrist sitting (middle) with his parents.

He would have come of age in the early 1890s. He presumably underwent religious training and initial trial congregation work, because he became the Rev. Edward Lloyd Sechrist. This was possibly in Cleveland. He married in Cleveland and he and his wife had two young children by 1905.

In Mashonaland:

As the Rev. Edward Lloyd Sechrist he had served as a teacher and evangelising missionary in Mashonaland, Rhodesia (East Central Africa). He “went in the field in 1905” according to one journal. Then he and his young family arrived at the Methodist Episcopal Mission at Old Umtali in October 1906 to serve there as “the agricultural man”, training locals in fresh vegetable production on the Mission farm. He also tested the ground with new useful crops, to see what might thrive there. Local species of fruit trees and bushes were planted by the thousands each year.

This Mission was “a large industrial training mission”, established in 1899 in the most trying and difficult circumstances, and in practice it seems that a teacher there had to be an ‘all rounder’ and a bit of a medical man as well. Bringing a doctor out for a visit cost fifty dollars. A history of Christian missions in Rhodesia notes that… “Mr Sechrist took charge of the Mechanical Department while Mrs Sechrist supervised the work in the primary school.” One of the first things they did was to grade the school classes much more efficiently by intelligence and aptitude. He found the boys capable of most types of basic craftsmanship and productive manual work, and hoped to marginally improve their future earning and homemaking capacity without forcing western ideals and standards on them. Mrs Sechrist also soon introduced musical instruction. The Rev. Sechrist, as well as supervising much building and fencing work, taught drawing and “has started the bee industry” at the Mission. These were, however…

“native wild bees which are extremely cross [fierce] and have many undesirable traits. We are getting some imported bees and hope to give a better report in a few years. The boys work with the bees very well and if it can be made a profitable industry it should be a good thing, as honey will sell at a good price.” (1907 report)

A daughter, Helen Alice Sechrist Osman, was born to the Sechrists at Old Umtali in January 1908. By summer 1908 the Mission was making strong local progress and the natives had turned from sullen to friendly. The Mission’s attention was thus turned to opening up ‘the interior’ districts, still hostile. For three months in the summer of 1908 the Rev. Sechrist tried, solo and living out of a rat-infested hut, to open up new missionary territory in the ‘interior’ districts of Mrewa and Mtoko. Sechrist found the natives suspicious and hostile to white men, and the tribal chiefs still adamantly refusing to allow the possibility of any local missionary station. The few white people living in these remote districts appear to have been just as unresponsive.

Return to America:

At the end of the summer of 1909 he returned to America, with his wife and three children. The Epworth Herald [Chicago] reported… “Mr. Edward L. Sechrist and Mrs. Sechrist of the Old Umtali Industrial Mission, East Central Africa, arrived in New York with their three children Monday, October 25.”

The family may have returned via London, which would be the natural stop on the route — Sechrist’s poem “Success”, found near the front of his 1947 edition of his intructional book Honey getting, remembered that forty years before… “I saw a wall in a palace-garden in England”. This he always remembered as ‘the perfect’ mossy vine-trailed sun-brushed wall. One thus imagines that the Anglophile Lovecraft would have once heard from Sechrist some memories of the autumnal palace gardens and streets of London at the height of Empire.

To Tahiti:

There is no trace of Sechrist in the online-accessible historical record from about 1910 to 1918. But it is possible to infer that he was in Polynesia as a missionary for at least part of this time. Lovecraft noted Polynesia in January 1922, after Sechrist had joined the United and thus become involved in Amateur Journalism in late 1921…

“One of our most distinguished new accessions is Mrs. Renshaw’s recruit, Edward Lloyd Sechrist, of Washington, D. C., whose powerful essay on Columbus will introduce him to United readers. Mr. Sechrist is studying advanced literature at Research University, and promises to be heard from in the future. He is a traveller and philosopher, with strong predilections for the more genuine side of Nature; and has spent much time in such remote places as South Africa and Polynesia.” (Lovecraft in News Notes, January 1922).

A profile in the journal Bees, unavailable except as a snippet, has…

“His seven years in Tahiti Sechrist later described as “the most delightful episode of my life”.”

We know he was in Tahiti in the 1930s so there may have been two such stays, the first being with his young family sometime during 1910-1918. Since Asia: Journal of the American Asiatic Association wrote in 1921 that…

“Sechrist lived in Tahiti with members of the Teva clan of poets — hereditary keepers of old stories and dance-songs.”

One result of this was Sechrist’s “The Shadow Folk” (Asia, April 1921). Possibly there are other such articles to be found.

Published writings on bees:

Rather than continue to develop his ethnographic work, Sechrist developed a more serious practical interest in bees and how to make bee-farming more efficient. It is probable that this was spurred by the needs of the First World War, as his first substantial bee publication Transferring bees to modern hives (Farmers Bulletin 961, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture) was in 1918. This date might suggest that he was in Tahiti 1910-1917 and then returned to America.

So far as I can tell he issued no publication of his own in the world of Amateur Journalism, nor any sort of amateur bee newsletter.

Meeting Lovecraft in 1924:

Sechrist entered Amateurdom in 1921 and met Lovecraft in person on a visit to Providence in February 1924. They evidently also corresponded, as The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is written on the back of Sechrist’s letters to Lovecraft.

He met Lovecraft in New York in November 1924…

“Early last November Mr. Edward Lloyd Sechrist of Washington spent some time in New York, absorbing many of its museums and antiquities under the guidance of the Official Editor [i.e. Lovecraft].” (Lovecraft, News Notes, July 1925).

A November 1924 letter in Letters from New York (page 85) confirms that the dating of this is indeed secure and News Notes is 1925 not 1926. Lovecraft records Sechrist arriving for “a week’s sightseeing among friends” and Lovecraft “prepared the Boys for Sechrist’s presence at the next meeting”. Thus it appears that Sechrist was, however briefly, sitting among the Kalems with Lovecraft.

Joshi, with access to all the Lovecraft letters, adds that…

“the two of them went to the Anderson Galleries on Park Avenue and 59th Street to meet a friend of Sechrist’s, John M. Price; Lovecraft had some dim hope that Price might be able to help him get a job at the gallery, but obviously nothing came of this.”

Price was a cataloguer with the gallery.

Around Washington in Spring 1925:

In April 1925 Lovecraft and Kirk visited Sechrist’s home ground for a whirlwind tour by speeding Ford car, Mrs Renshaw at the wheel…

“In April, accompanied by George W. Kirk, he [Lovecraft] paid a hurried visit to Washington and its Virginia environs; where the benevolent and expert guidance of Mrs. Renshaw and Mr. Sechrist enabled him to see much [in one day]” (Lovecraft, News Notes, July 1925).

“Lovecraft, Kirk, and Sechrist first made a walking tour of the important landmarks in the city centre, noting the Library of Congress (which failed to impress Lovecraft), the Capitol (which he thought inferior to Rhode Island’s great marble-domed State Capitol), the White House, the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and all the rest. Renshaw then drove them to Georgetown, the colonial town founded in 1751, years before Washington was ever planned or built. Lovecraft found it very rich in colonial houses of all sorts. They then crossed the Key Memorial Bridge into Virginia, going through Arlington to Alexandria, entering the Christ Church, an exquisite late Georgian (1772–73) structure where Washington worshipped, and other old buildings in the city. After this, they proceeded south to Washington’s home, Mount Vernon, although they could not enter because it was Sunday. They drove back to Arlington, where, near the national cemetery, was the residence called Arlington, the manor of the Custis family. They also explored the cemetery, in particular the enormous Memorial Amphitheatre completed in 1920, which Lovecraft considered “one of the most prodigious and spectacular architectural triumphs of the Western World.” Naturally, Lovecraft was transported by this structure because it reminded him of classical antiquity — it was based upon the Dionysiac Theatre in Athens — and because of its enormous size (it covers 34,000 square feet). They then came back to Washington, seeing as much as possible before catching the 4.35 train back to New York, including the Brick Capitol (1815) and the Supreme Court Building. They caught the train just in time.” (S.T. Joshi, I Am Providence).

With Lovecraft in New York in late 1925:

Lovecraft’s Letters state that Sechrist was again coming to New York in June 1925 and “bringing two of his children”, when Lovecraft was anticipating meeting him again. (Selected Letters II, page 10). Possibly the trip was delayed, as Lovecraft’s day-by-day skeleton diary for 1925 makes no mention of him during June 1925.

The two men certainly met again in New York in late 1925, according to Lovecraft’s New York skeleton diary and confirmed by Letters from New York. Lovecraft talked on the telephone with Sechrist in advance of a visit. Lovecraft appears to have talked with him on the phone until after midnight, on the 12th-13th December. Lovecraft’s diary then has him meeting Sechrist on the 14th, 16th and 17th December, the last date being when two museum visits and a gallery occurred…

“AM. Mus., Met. Mus. bus to library — gallery & reading room — els lv.”.

‘ELS lv.’ = ‘Edward Lloyd Sechrist leaves’.

During this time Sechrist was again sitting among the Kalems with Lovecraft one evening (Letters from New York, page 253). Evidently the visit led Lovecraft to spruce up his dingy low-life apartment beforehand, even going to far as to wash the windows and curtains.

As was his wont, Lovecraft included Sechrist in his 1925 round of Christmas odes to friends, “May Polynesian skies thy Yuletide bless”.

Honey production and classification:

Sechrist continued his rapidly ascending career in the world of bee culture. There is evidently a mis-transcription in Selected Letters II when Lovecraft talks of…

“my old friend Edward L. Sechrist of the government bookeeping dept., a delightful aesthete & poet with a predilection for primitive life, who has spent much time in Africa & the South Sea Islands.”

“Bookeeping” should obviously read “beekeeping”.

Sechrist’s booklet The Color Grading of Honey appeared in 1925, in which some may see an interesting parallel to Lovecraft’s similar concern with colour gradations in “The Colour Out of Space” (1927).

In 1927 he wrote the technical report United States Standards for Honey for the United States Department of Agriculture, setting out in tight detail the nation’s recommended standards for all forms of the substance. When Americans buy or eat honey they can thus thank Sechrist for helping to ensure that it meets a set standard.

In 1928 he wrote a report on honey production in the Intermountain States of the U.S. This reveals that he was by then an Associate Apiculturalist at the Bureau of Entomology, Dept. of Agriculture. The field research undertaken for this report was likely why he was not at home when Lovecraft was in the area…

“He tried to look up Edward Lloyd Sechrist, but found that he was away on business in Wyoming.” (S.T. Joshi, I Am Providence)

Stymied, Lovecraft instead took a $2.50 four-hour bus-ride out to the Endless Caverns of Virginia, whence he descended. Thus giving us Lovecraft’s marvellous account of “A Descent to Avernus”, written Summer 1928.

Washington and Great Zimababwe:

In Lovecraft’s Travels in the Provinces of America (1929) he states that he had again taken trips with Sechrist, when in Washington in 1929…

“In many of my trips I was ably guided by my friend Edward Lloyd Sechrist, Esq., whose courtesy contributed so much to my Washington trip of 1925.”

This was when Lovecraft heard Sechrist’s most substantial account of visiting the ruins of the fortress at Great Zimababwe. The account, and more specifically the authentic artefacts that Sechrist had by then acquired, inspired Lovecraft’s long and languorously weird African poem “The Outpost” (1929)…

“he shewed me many rare curiosities such as rare woods, rhinoceras-hide, &c. &c. — & especially a prehistoric bird-idol of strangely crude design found near the cryptical & mysterious ruins of Zimbabwe (remnants of a vanished & unknown race & civilisation) in the jungle, & resembling the colossal bird-idols [eagles] found on the walls of that baffling & fancy-provoking town. I made a sketch of this, for it at once suggested a multiplicity of ideas for weird fictional development.”

Sechrist’s first-hand account and newly revealed artefacts would seem to have arisen from a more recent visit to Africa in the later 1920s, rather than from his missionary work back in the 1900s. One then suspects that Sechrist may have re-visited Old Umtali to set up modern commercial bee hives at the Mission there, and to train the Mission in the art of advanced bee-keeping. There is as yet no confirmation of a 1920s visit, though, that I can find.

However, evidently Sechrist had already discussed Zimbabwe with Lovecraft back in 1925, since Lovecraft mentions the fortress in his 1925 poem to Sechrist, “May Polynesian skies thy Yuletide bless” etc. This has the line “Zimbabwe’s wonders hint mysterious themes”. There is also an account of Lovecraft being intensely interested in a discussion of Zimbabwe with Sechrist, had in December 1925. (Letters from New York, page 256). For more on the extended influence Zimbabwe had on Lovecraft see my essay “H.P. Lovecraft and Great Zimbabwe”.

A leading bee specialist:

In 1930 Sechrist developed a lantern slide (slide-show) presentation on bee-handling, for presentation to farmers in remote rural districts during the early part of the Great Depression. He also undertook radio talks on beekeeping. His books show he was a competent photographer, and used photographs in his work and books, something begun as far back as the 1900s when he did “considerable photographic work” at his African Mission. Sadly he doesn’t appear to have left us any pictures of Lovecraft.

In April 1932 Lovecraft writes that…

Sechrist — the bee expert — is now stationed in Davis, California.

This was the Pacific Coast Bee Culture Field Station at Davis, California. In 1931 this was less grand than it sounds, with Frontier Bees and Honey magazine stating that…

“we understand almost the only equipment now on hand is the staff of workers, now occupying a large bare room in the Animal Science building”

One source on Sechrist mentions his “first marriage”, so presumably there was a second marriage, and the early 1930s move across the nation might (at a guess) have been connected with that? Apparently his second wife was a nutritionist. But more probably the move out west was due to pressure on the government from the booming Californian bee-farmers, who wished to have their share of the top national consultants. Such matters could be easily clarified, if only outdated copyright laws did not hinder access to much defunct 20th century material. The same can be said of Sechrist’s books, all but two of which are on copyright lockdown.

The 1944 introduction to the 1947 second edition of his standard introduction to commercial bee farming, Honey Getting (Bee Master Series), states that he worked at the U.S. Bee Culture Laboratories at Washington D.C. and in California. He published several other major books such as Amateur Beekeeping and Scientific Beekeeping, as well as articles in the likes of the American Bee Journal.

In Polynesia (again):

On Lovecraft’s death, the instruction was to send certain manuscripts to Sechrist in Tahiti…

Mss. of Polynesian folklore with pictures [to] E. L. Sechrist, Box 191, Papeeti, Tahiti.

We have to then assume that Sechrist was living in Tahiti in the mid 1930s, and that he was almost certainly assisting bee farms there. Barlow duly sent the required parcel away to Tahiti, on Lovecraft’s death.

Update: Some information on the post-retirement life of Lovecraft’s friend Sechrist, from the USDA Employee Newsletter, 12th June 1944…

Possibly this folklore collecting, presumably done by Sechrist himself in Tahiti, was why de Camp stated in his biography of Lovecraft… “Edward Lloyd Sechrist, an anthropologist of the Smithsonian Institution.” Lovecraft states in Selected Letters IV that…

“My friend Sechrist (the ex-Washingtonian bee expert) lived in Tahiti for years — close to the natives — & studied their folklore in detail.”

We know this was true of the 1910s, and that he did gift a full-size traditional outrigger Hawaiian fishing canoe to the Smithsonian (catalogued in 1923, but perhaps acquired earlier than that date). Possibly he also deposited his Tahitian folklore notes and manuscripts. However I can find no record of these, nor any mention of Smithsonian links during the 1930s or later.

As a poet:

Lovecraft evidently considered Sechrist a poet in the 1920s. One Sechrist poem appears in his Honey Getting (1945/47), and possibly more may be found. There appears to have been no poetry collection.

Obituaries:

Sechrist died at his home at Escondido, California, aged 81, following a stroke. I regret there are no obituaries freely available online, nor can the several profile articles on Sechrist in bee publications be had. The Canadian Bee Journal does provides a substantial snippet which offers context for his career…

“Edward Lloyd Sechrist, during his lifetime of 81 years, spanned the years from the early attempts to bring modern beekeeping into practice then the rush to large scale commercial beekeeping and lately, to methods to improve bee brooding.”

His best publicly-available tribute is to be found in Honey Getting…

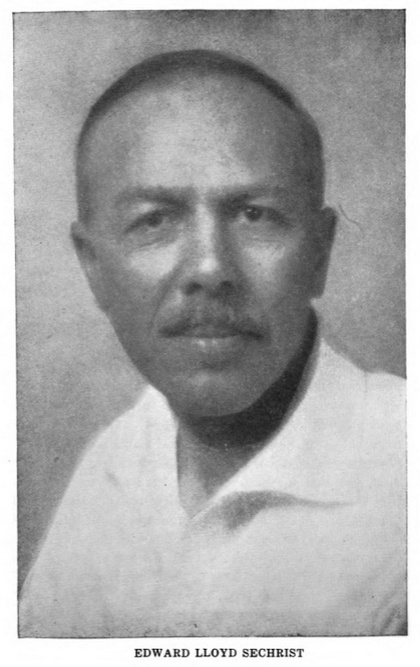

Sechrist as Lovecraft would have known him. The three blurry dots are probably large bees.

Sechrist as Lovecraft would have known him. The three blurry dots are probably large bees.

There appears to be no archive of his papers, photographs and correspondence.