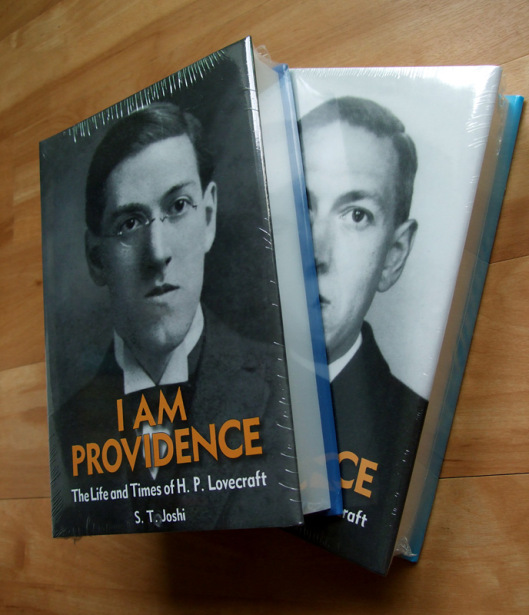

Some quotes on Lovecraft’s Waterman fountain pen, rescued from the clutter of an old discussion thread on the Fountain Pen Network forum (several kindly supplied to the Network by Chris Perridas). Illustrated here with photos of a 1920 No.56 Ideal Waterman, without gold decoration, currently on sale to collectors in Taiwan, plus a few others of the same time-period. They apparently sell for upwards of $800 in really good condition.

“But avaunt [Go away], dull care! Let me drown my worries in watered ink, or the clatter of Remington [typewriter] keys.” — Lovecraft letter, in Lord of a Visible World: an autobiography in letters.

“You’ll recall that I obtained a pen a piece for SH (Sonia) & myself last October at a price of $1.28 … we found the sale still on [&] the salesman still willing to make exchanges. …to obtain real satisfaction one must invest in a real Waterman … I did not escape from the emporium till a $6.25 Waterman reposed in my pocket — a modern self-filler corresponding to the ancient $6.00 type which I bought in 1906 & lost seventeen years later amidst the sands of Marblehead Neck in the summer of 1923 … the feed is certainly a relief after sundry makeshifts — tho’ I think I’ll change this especial model tomorrow for one with a slightly coarser point — one less likely to scratch on rough paper. It is certainly good to be back among the Watermans again …” — Lovecraft to Lillian Clark on 30th January 1926.

[The “sundry makeshifts” apparently included a self-filling Conklin, loaned from Moe after Lovecraft’s pen was lost “amid the sands of Marblehead”].

From: Howard Phillips Lovecraft: Dreamer on the Nightside, by Frank Belknap Long…

Howard was fascinated by small articles of stationery — writing pads, rubber bands of assorted sizes, phials of India ink, unusual letterheads, erasers, mechanical pencils, and particularly fountain pens.

He used one pen, chosen with the most painstaking care, until it wore out, and several important factors entered into his purchase of a writing instrument. It had to have just the right kind of ink flow, molding itself to his hand in such a way that he was never conscious of the slightest strain as he filled page after page with his often minute calligraphy. It also had to be a black Waterman; a pen of another color or make would have been unthinkable.

When a pen he had used for several years wore out, the purchase of a new one became an event — lamentable in some respects, but presenting a challenge which I am sure he secretly enjoyed. We were walking northward from Battery Park [New York City], where I had met him at noon, stopping occasionally to admire one of the very old houses which still could be found scattered throughout the financial district in the 1920s, when he told me that he intended to purchase a new pen at the first stationery store that had a well-stocked reliable appearance. He removed the old one from his vest pocket and showed me how worn the point had become. I found myself wondering just how many letters and postcards he had written with it, for it did have a ground-down aspect.

We walked on for three or four blocks, found the kind of store he had in mind, and I accompanied him inside. The clerk who waited on him was amiable and greeted him with a smile when he asked to try out a number of pens.

“The point has to be just right,” Howard said. “If it won’t put you to too much inconvenience, I’d like to test out at least twenty pens.”

The clerk’s smile did not vanish when Howard turned to me and said, “I’m afraid this will take some time.”

It was just a guess, but I felt somehow that he had made the kind of understatment that would strain the clerk’s patience almost beyond endurance.

“We just passed a pipe store,” I said. “I’d like to go back and look at the window again. I may just possibly decide to buy a new pipe. I can be back in fifteen or twenty minutes.”

“No need to hurry,” he said. “I’ll probably be here much longer than that.”

I was gone for forty-five minutes. It was inexcusable, I suppose, but it was a clear, bright day, a wind with a the tang of the sea was blowing in from one of the East River wharves where several four-masted sailing ships were tied, and I decided to go for quite a long walk instead of returning to the pipe shop.

When I got back to the stationery store, there were at least fifty pens lying about on the counter and Howard was still having difficulty in finding one with just the right balance and smoothness of ink flow. The clerk looked a little haggard-eyed but he was still smiling, wanly.

The careful choice of a fountain pen may seem a minor matter and hardly one that merits dwelling on at considerable length. But to me it has always seemed a vitally important key to the basic personality of HPL in more than one respect. He liked small objects of great beauty, symmetrical in design and superbly crafted, and by the same token larger objects that exhibited a similar kind of artistic perfection. And the raven-black Waterman he finally selected was both somber and non-ornate, with not even a small gold band encircling it. That appealed to him in another way and was entirely in harmony with his choice of attire.

“I certainly share your despair in regard to ever finding a serviceable fountain-pen — it’s the main reason why I have taken to typing most of my letters. I, too, often employ pencils in making the first draft of a story — though such drafts, with me, are likely to get themselves done any old way. Sometimes I start ’em on the machine — and then finish up or alternate with all the available mediums of scripture. I don’t dare leave the resultant mass lying around too long before making the final typed version — or even I would be powerless to unscramble it!” — letter to Clark Ashton Smith in March 1932.

Cover for Neonomicon #3.

Cover for Neonomicon #3.