A December ride, hare-hunting with the Buxton and Peak Forest Hunt. By Edward Bradbury, published in his book In the Derbyshire highlands (1881).

“I think the girls have gone mad,” was the Old Lady’s remark as every room at Limecliffe Firs seemed to resound with silvery shouts of “Hark forrard!” “Tally-ho!” “Yoicks!” “Hey, ho, Chevy!” And other exclamations, ecstatic but inexplicable, peculiar to the vocabulary of huntsmen.

It was a December evening preceding a meet of the Buxton and Peak Forest Harriers. The Young Man was to join the hunt. It had also been arranged that the two young ladies and the present writer should drive to the scene of action in the pony carriage.

This had not been settled without some protest from the prudent Old Lady. She remembers the gloom of a certain grey November day in the years agone when the dangers of the chase were personally illustrated at Limecliffe Furs. But a broken limb has not diminished the Young Man’s ardour. It was amusing to hear the animated logic with which he overcame the opposition of the solicitous Mother of the Gracchi. [i.e.: the ideal of the Ancient Roman matron]. His arguments were founded on both moral and physical grounds.

“A run with the harriers” he contended “promotes health, fosters courage, requires judgment, teaches perseverance, develops energy, tries patience, tests temper, and exercises every true virtue. It is recreation to the mind, joy to the spirits, strength to the body. To be a good huntsman was to be a fine manly fellow: a ‘muscular Christian, ‘if you like, but a ‘muscular Christian’ as was Charles Kingsley, the patentee of the phrase. Fishing teaches patience; but just look, my nephew, at the number of moral lessons inculcated by hunting. Care and diligence are required ‘to find’. ‘Look before you leap’ was an aphorism of practical wisdom derived from Nimrod and not Solomon; while ‘Try Back’ was another phrase which might be wisely applied to daily life.

‘Try Back’ when an obstinate hound misleads a pack, and it is found that the trail so diligently sought is hopelessly lost. ‘Try Back’ renews hope and rewards perseverance. ‘Try Back,’ then, in the larger field of life, with its vexations, disappointments, lost chances, and broken hopes. If led into error, ‘Try Back;’ if success is denied thee in that wearisome up-hill toil, ‘Try Back;’ baffled, blighted, broken-on-the-wheel, ‘Try Back.’ Is thy trust betrayed, and thy love false ? Then ‘Try Back.’ There ia a false scent somewhere; a mistake has been made at some critical juncture, so ‘Try Back,’ and a second quest shall give thee splendid recompense.”

There was much more of this eloquent hunting homily, which threw such a glamour of sentiment over hares and horses and harriers that the Old Lady, fond of sermons, gradually relented in her scruples. She finally surrendered when she heard that hunting the hare took precedence of fox hunting, since the fox did not afford half so much genuine sport, and while the flesh of the former was delicious, that of the latter was so much filthy vermin.

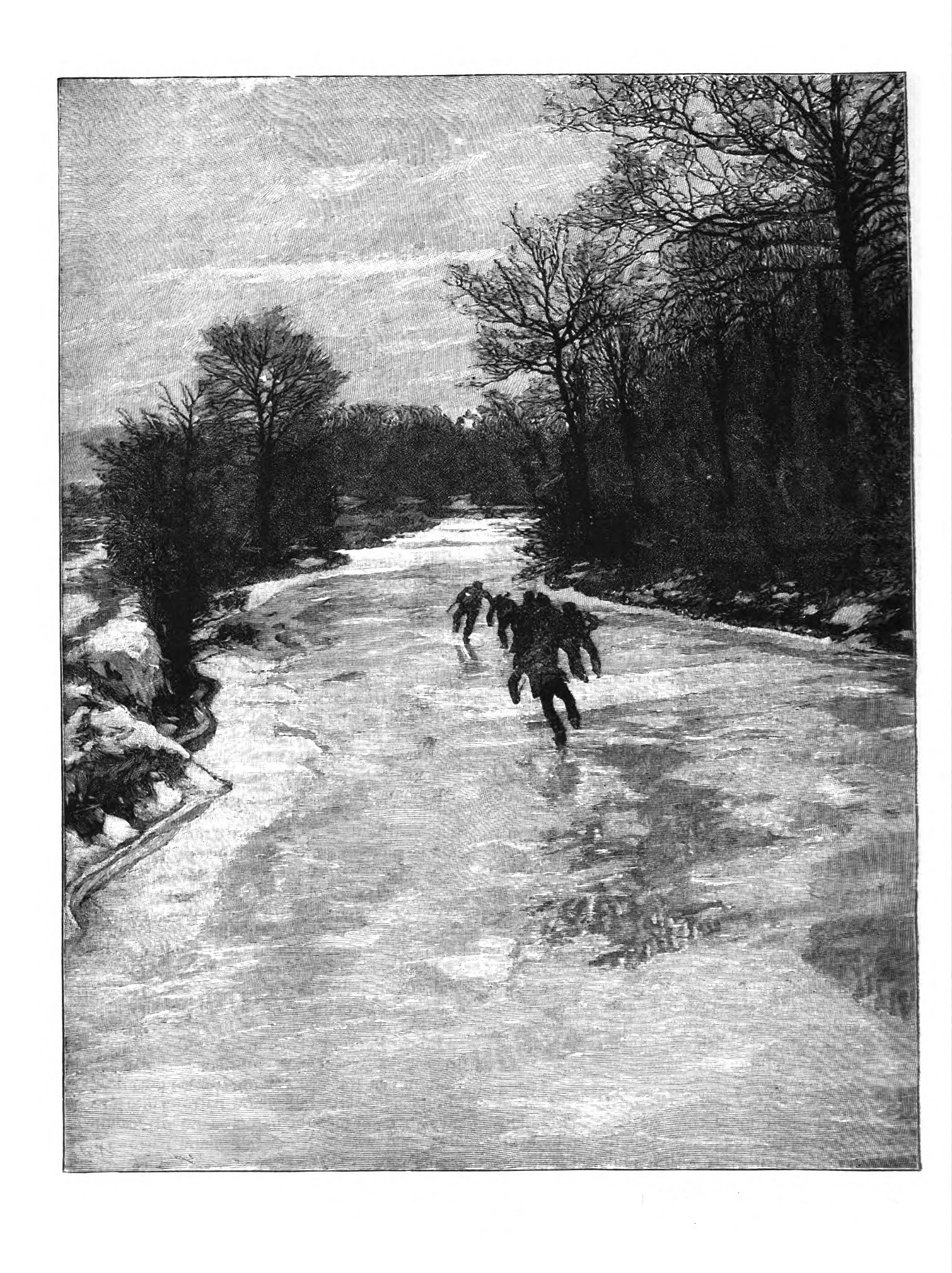

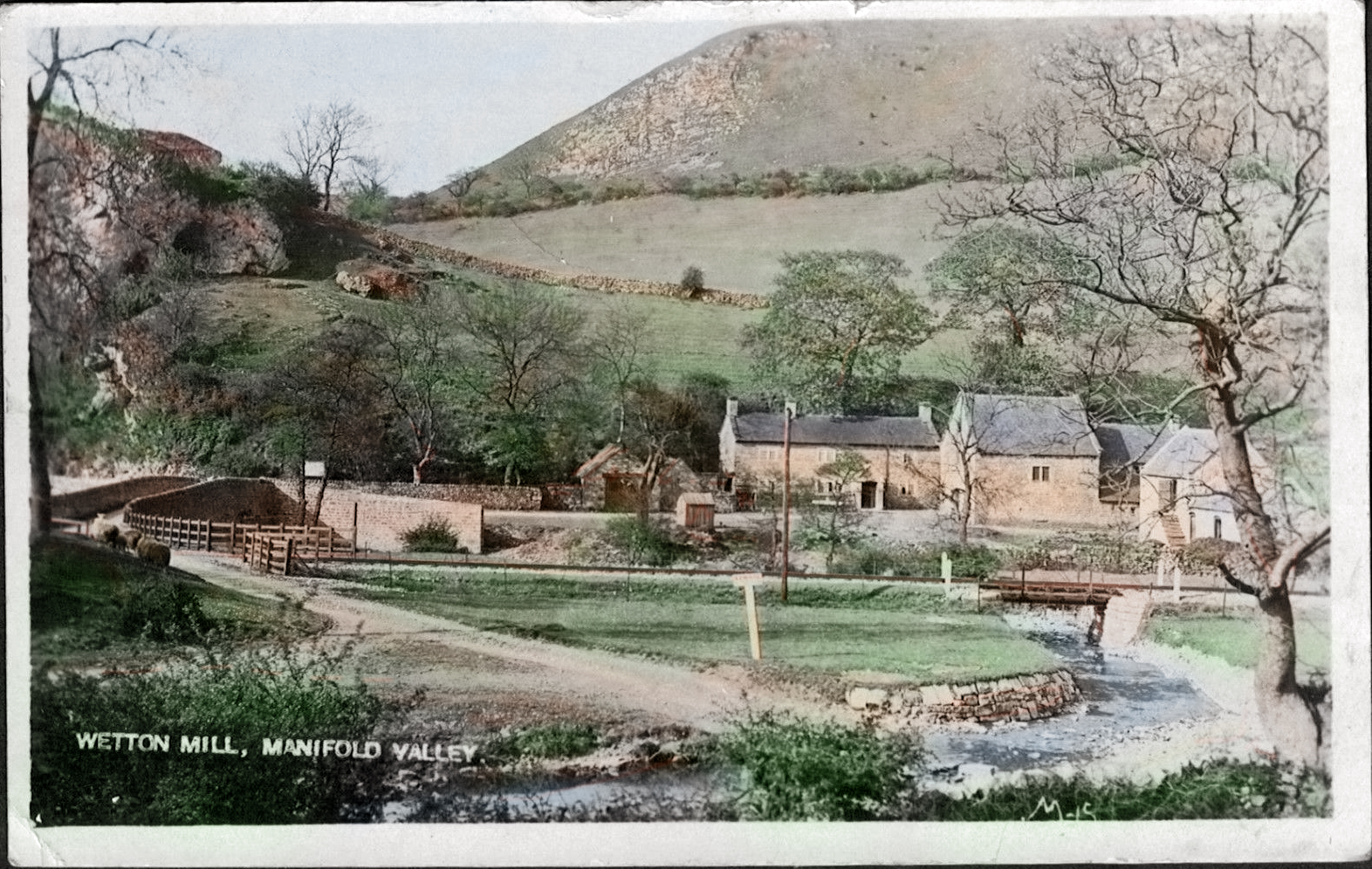

I cannot go the length of giving the hunting of the High Peak a place before that of the Quorn Country; but the wild picturesqueness of Derbyshire, with its loose stone walls and steep mountain declivities, imparts a charm and an excitement to the sport which is unknown to the red-coated horsemen of the monotonously flat fields of Leicestershire. The wonder is that Buxton in the winter season does not become as much a hunting centre as Melton Mowbray or Market Harbro’. There are three packs of harriers of established reputation, meeting twice or thrice a week within easy distance of the popular watering place. The Dove Valley Harriers that answer the wild “Tally-Ho!” in the picturesque landscape watered by the Dove. The High Peak Harriers that have their meets either at Parsley Hay, a Wharf on the High Peak line of railway; or Newhaven, a solitary hostelry at the meeting of several roads and a famous house enough in the coaching days; or at Over Haddon, by the Lathkill Dale. And the Buxton and Peak Forest Harriers, which generally start from Peak Forest, or from Dove Holes, and pursue the rough and romantic countryside historically famous as the hunting ground of kings.

It was the latter pack that the Young Man had elected to follow on the morning after that December evening when the house was alive with silvery echoes of the hunting field. The weather had during the past week or two attested that there was something radically wrong with the Zodiac; but on that night, as we looked out from the glow and warmth of the room, the air was keen and clear; the moon shone with an intense white electric light; the roofs glittered in the cold radiance; every detail of architecture was revealed in a sharp relief that made the shadows ebony in their deepness; the gas lamps burned with a dirty yellow; but there was not enough frost to affect the morrow’s enjoyment.

A grey morning follows that glistening night.

“The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve”.

“The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve”.

The mist lies thick upon the hills. The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve; and the Young Man, with the snow of sixty winters in his beard, seems part of his chestnut cob as he rides in black coat, green vest, and corduroys, by the side of our pony carrriage. Raw and cold is the dull ride across Fairfield Common [now on the northern edge of Buxton]; but we have foot warmers in the conveyance, and quite a panoply of soft shawls; while it makes one feel quite snug and warm to contemplate the sealskin of Somebody and the furs of Sweetbriar.

Presently the sun warms the grey fog until the country seems to float in a golden mist; a mellow amber light, such as [the painters] Turner and Claude Lorraine loved to introduce in a poetic atmospheric effect.

There is animation at Dove Holes. A score or more well-mounted horsemen make picturesque patches against the ridges of sombre hills; there are one or two farmers on well ribbed-up horses; there is a lady, well-known to the county as a bold rider, on a sturdy grey mare that is pawing with impatience to charge the stone walls; there is an old gentleman with the gout in a bath-chair, who is anxious to witness the “throw off; ” there are one or two carriages and antiquated gigs; while the number of camp-followers on foot show how potent is the spell of sport among all classes when “the Horn of the Hunter is heard on the Hill.” The keen harriers are with the huntsman, Joe Etchells, the men and boys on foot are grouped around, and take an intelligent interest in the preliminary proceedings. There is the Judge Thurlow look of wisdom on canine countenances, solemn in its sagacity. Presently the Master is seen riding along the road from Buxton, with other well-known members of the Buxton and Peak Forest Hunt. Somebody, who regards everything from what Thackeray called “a paint pot spirit,” [one who thinks in pictures] talks of the hunting groups [in the art of] of Wouvermann, and the horses and hounds of Eosa Bonheur.

Sweetbriar is intently silent : but she makes, nevertheless, a very pretty element in the picture.

And now, behold! The first quest is successful, and cavalry and infantry are instantly scattered in picturesque disorder. It is a picture full of movement; and the broken undulating features of the country, with broad valleys and bold hills, show it up in all its artistic charm. The present hare, however, soon succumbs, and the hounds are thereby “encouraged.” And now the wiry Master of the Pack gives the order for a second quest. The cry comes that another hare has “gone away !” She is in full flight; the alert hounds follow in swift pursuit; this time the chase grows exciting.

People who derive their notion of Puss from Cowper’s hares have an attractive lesson in natural history prepared for them by a hunt with the harriers. [Cowper was a poet who famously reared tame hares]. The celerity of the mountain hare is only exceeded by its subtlety, which exceeds even the cunning of Master Reynard [the fox]. The intellect of the hunter and the instinct of the hounds are taxed to the uttermost by the shifts and doubles and dodges of their ” quarry.” The buck hare, now, after making a turn or two about his “form,” will frequently lead the hunt five or six miles before he will turn his head. But madam is more wily. She delights in harrassing and embarrassing the hounds. She seldom makes out end-ways before her pursuers, but trusts to sagacity rather than speed. See ! Now she is off and the harriers are in hot pursuit. Riders are spurring their horses up the slope. A good run at last, we say. The harriers are well-nigh their prey. Puss sees the intervening distance lessening; for a hare, mark you, like a rabbit, looks behind; and suddenly she throws herself with a jump in a lateral direction and lies motionless. The manoeuvre is a success. The hounds fly past deceived by the diplomatic twist. They pull up at last exasperated.

The scent is lost.

“These ‘ill ‘ares is as fawse as Christians,” says a beefy-faced country man, with steaming breath.

Pedestrians appear to have an advantage over the horsemen. Only at intervals comes the wild and thrilling cross-country “charge of the light brigade,” the spurred galop that belongs to stag or fox-hunting.

The rest is made up of occasional spurts and pauses, for the hare’s flight is made in circles. The infantry can thus keep the cavalry in constant sight. Sometimes, indeed, they have better chances than the mounted Nimrods.

Another “find.” The harriers are now “getting down” to the deceptive turnings of Puss. The wild rush clearly won’t do, they intuitively argue; and so with strange intelligence they resolve to keep themselves in head, and, with nose to ground, determine to checkmate the craft of the game with a responsive craft. They take the trail up with intellectual sagacity. Finding her “doublings” of little use now, Puss makes across a turnip field for the hill.

“She’s for Peak Forest or Sparrow Pit !” is the cry of the crowd. The pack plod up hill. “Hark to Watchman !” “Follow Watchman !” is the hurried command. The lady of the hunt is now neatly leading. Esau follows. The young man is showing his sturdy back to a field of flagging horses. A narrow stream, tumbling between steep banks over rocky boulders, presents itself. Some of the horsemen seek an easier avenue. One, more adventurous, who rides in a long mackintosh coat, takes a “header” in the water. He scrambles out soaked to the skin. “A good job tha ‘ browt thi ‘ macintosh wi ‘ thee!” Says a consoling country friend to the dripping rider as he seeks the bank of the stream.

It is “bellows to mend” before the steep stony summit of Beelow is reached. We can see the white steam from the horses ‘ nostrils. The hare, being able to run faster up hill than down, has the pull over horse and hound. Before the top of the stubborn hill is gained, however, she has a premonition of danger ahead. A sudden turn; and she bounds through a flock of sheep and under the very legs of the horses toiling up the ungrateful ascent. The hounds turn and tear down after the scent in relentless pursuit. A stout farmer comes a crucial cropper over a stone wall. Half of the loose limestone boulders fall over him. ” Oh! Is he hurt?” demands Somebody with startled solicitude, while horse and rider lie together. “Noa, not ‘im; he’s non hurt; ha fell on ‘is yed,” says a sympathetic yeoman at the post of our observation.

Now puss takes the wall, and passes down the road. She skirts the very wheels of our carriage.

We see her startled brown eyes, the long hair about the quivering mouth, the beautiful silky ears thrown back in an agony of strained alertness; the soft colour of her winter fur. Fly past the dogs. Come the hunters. Boys on foot beat galloping horses in their fleetness. There is a wild clamour as the pack pelter down hill. It is irresistible. The excitement is intoxicating. Somebody and Sweetbriar are racing after the pursuers. Even the gouty old gentleman in the bath-chair gets out and hobbles along as if he had lost his head. A woman from a cottage close by rushes out with a frying pan in her hand; among the crowd is a village bootmaker, with his hat off and his apron on. I have known staid tradesmen on similar occasions also take to flight at the thrill of the clear “Tally-ho !” Men, mark you, who are as sedate and phlegmatic as Dutchmen under any other circumstances, and never knew a faster pulse of life.

Lo! The hare doubles again; but the harriers are upon her. We are close by at the finish. Poor Puss utters a death-cry, piercing in its helpless pathos. It is like the sobbing appeal of a child.

Sweetbriar begs for the doomed life to be saved; and the exasperated harriers, eager for blood, are driven off, so that she may have the beautifully shaded coat. But the timid creature is dead, and the frightened eyes are glazed.

When the hunters get together in close company, there are one or two black coats, green vests, and corduroys that are dabbed in dirt, and nearly every horse is blowing, after the sharp burst over the hilly country. Refreshment is in demand at a roadside tavern. The beverage most in favour is a curious alcoholic mixture, very popular among Derbyshire huntsmen, and known as “thunder-and-lightning.”

It is composed of hot old ale, ginger, sugar, nutmeg, and gin. On paper this appears a dreadful draught, worthy of Lucrezia Borgia [a famous poisoner]; but the eagerness with which it is quaffed this December afternoon is practical proof of the inspiring effect of the stirrup-cup on the exhausted Actaeons of the Peak [reference to the mythical hunter of Ancient Greece].

This is the last run of the day, for the short-lived sun is setting in red behind the moorland edges, and the amber mist is deepening into fog. We drive home in the waning light, exhilarated with the stirring incidents of the day. The young Man has much to tell us, as he ambles along by our side, of spirited passages in the hunt which had escaped us, and which sound like an Iliad to our ears.

At Limecliffe Firs to-night we discuss at supper the plump hare of the hunt, whose pitiful cry of pain we heard as it died. And we find that the healthful air, the joyous freedom, the excitement and the exercise of the day, have made us too grossly gastronomical to feel sentimental over devouring our victim.

But why is Sweetbriar absent from the table ?