The Birmingham Oratory, at about the time (1902-1911) that Tolkien and his brother would have been boys there. Two boys can just about be seen peeping out from under the shady trees.

Monthly Archives: July 2018

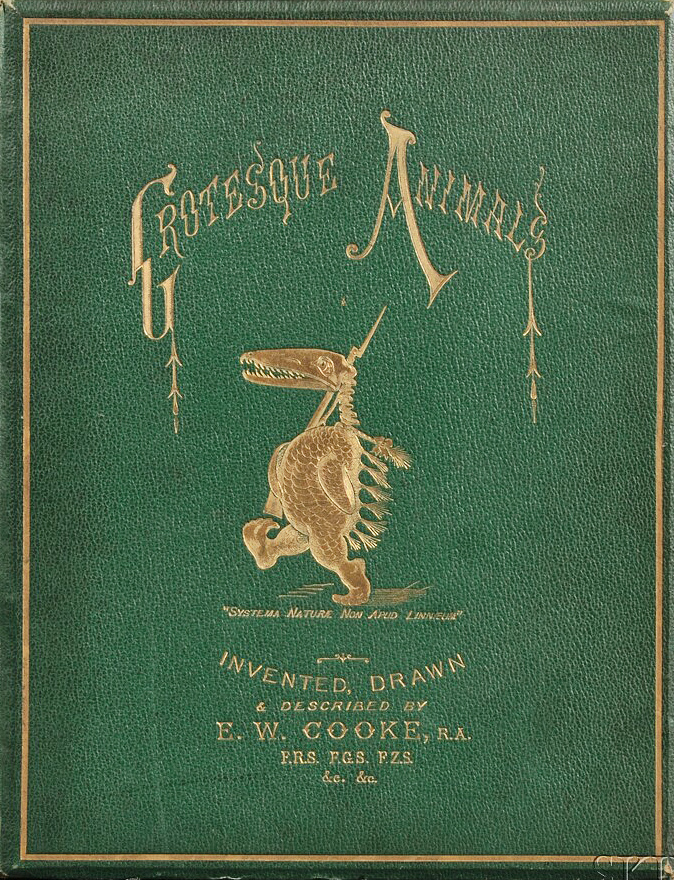

Grotesque Animals (1872)

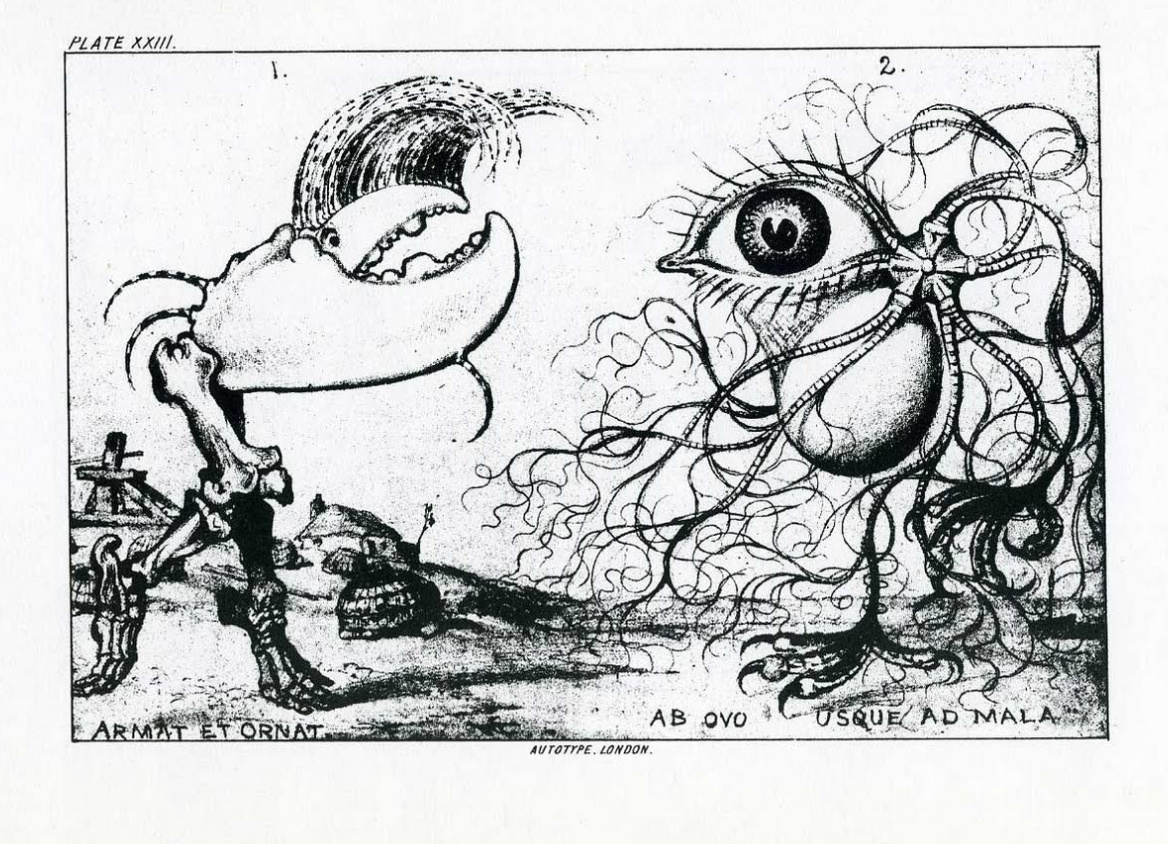

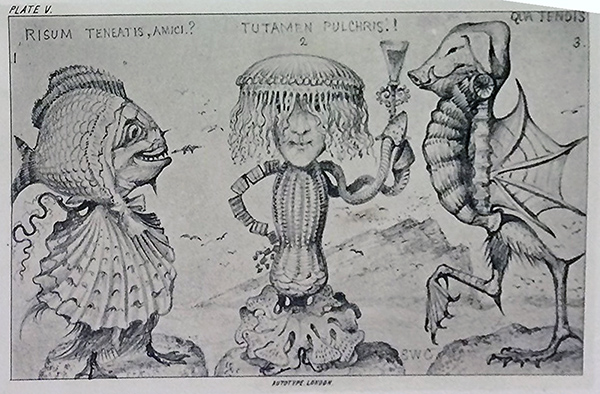

Grotesque Animals: Invented, Drawn, and Described by E.W. Cooke (1872), co-creator with James Bateman of eccentric gardens at Biddulph Grange in North Staffordshire. The book followed Lear’s Book of Nonsense by a few years, but the drawings were begun in 1864, a few years after Biddulph Grange was completed and Bateman had sold up and moved away. The book has 24 plates, not well reproduced here in this partial 14-plate reconstruction, as subtle shades and tones are lost. Each monster is explained briefly on a following page, but only one of these text pages can be found.

Plate V – too small to include in the partial reconstruction…

“Smutts on thowl washin’ agin…”

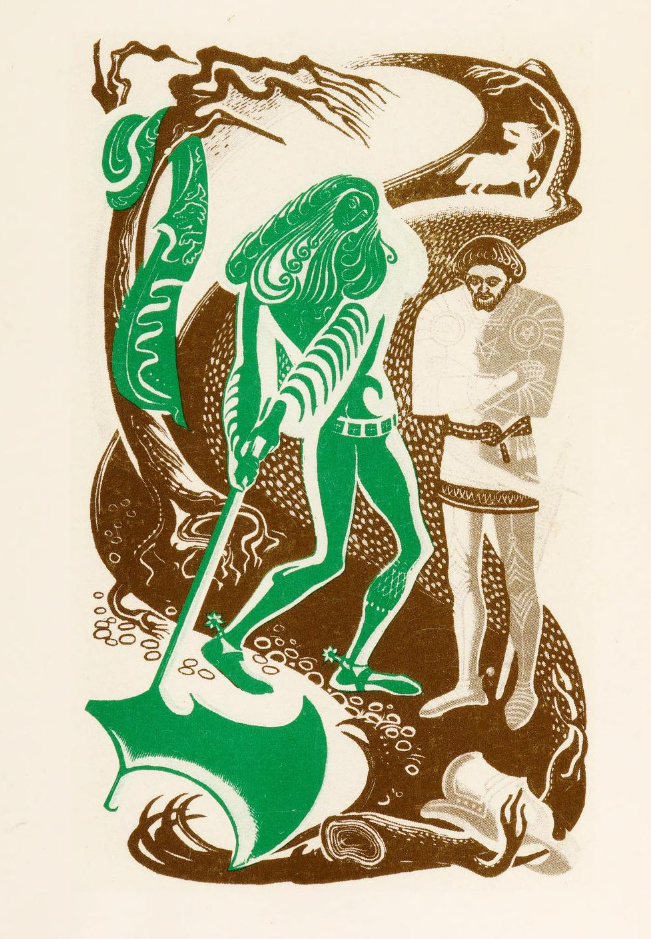

Sir Gawain illustration

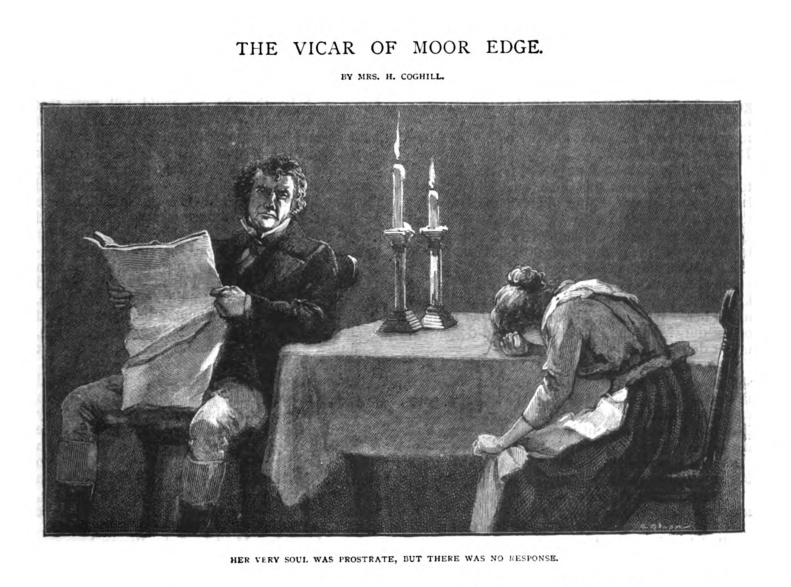

The Trial of Mary Broom

Another Potteries novel, found. The Trial of Mary Broom, 1894. If it is set partly in Burslem, then it may have some interesting descriptive scenes of the town.

“The Trial of Mary Broom, by Mrs. Harry Coghill [b. Brewood, 1836, lived Staffordshire c. 1884-1891], is a story of good plot, interest, and quick exciting movement. It is founded, it would seem, upon historical events, in which the principal actors were the brother Elers, Dutch potters, who left their own country during the reign of their great countryman, William III., and settled at Bradwell, near Burslem. Their proficiency in their trade excited the jealously of their English neighbours; and a real or imaginary conspiracy against them provides Mrs. Coghill with a motif, which she has skilfully and pleasantly utilised. The Trial of Mary Broom is a capital tale.” — Academy and Literature review.

Fairly short at 160 pages, it was her sixth novel and was apparently part of the ‘Homespun’ series for women. She also published a Moorlands short story, “The vicar of Moor Edge” in Leisure Hour, 1895. This probably gives a taste of what The Trial of Mary Broom would be like if it could be obtained.

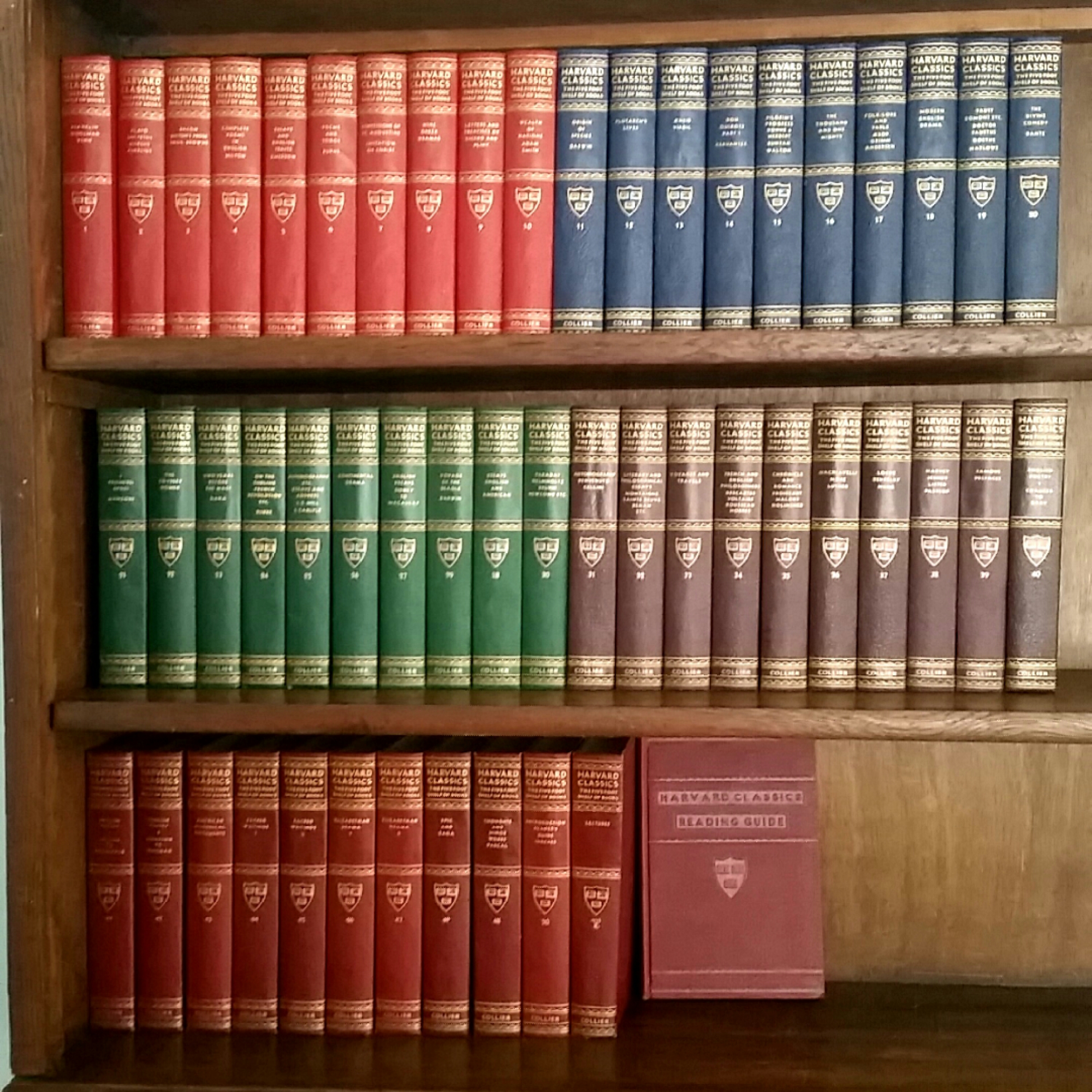

Complete 51-Volume Harvard Classics

The Complete 51-Volume Harvard Classics (1909-10), now officially available free in PDF. Buying a fine set in print would cost you around $600 or more. Includes beautifully edited and presented pre-PC volumes of The Thousand and One Nights; Folk-Lore and Fable: Aesop, Grimm, Andersen; and Epic and Saga. Volume 50 appeared in 1916 and provided “Introduction, Reader’s Guides, Indexes”, including eleven carefully designed ‘reading plans’ based on a set amount of reading each day. Thus it is not necessary for the rather daunted reader to just start at Vol. 1 and plough on from there. Volume 51 is a printed series of public lectures on the series.

Potiphar’s Wife by Kineton Parkes

Another local author, found. Kineton Parkes (1865-1938) was a Birmingham man from Aston, who from 1891 to 1911 was curator and principal of the Nicholson Institute in Leek. He was also was the manager-actor of the Leek Amateur Operatic Society for 1899, and generally appears to have been a leading light of the town’s cultural life.

During this time he developed an interest in walking and thus naturally encountered the Roaches, Morridge and the Manifold Valley. This led to his Potiphar’s Wife (1908), a novel of farm life in the Moorlands/Peak and with a good deal of dialect. Apparently it was set circa the ‘hungry’ 1840s and the economic recession of the time (triggered by natural events which began with a massive volcanic eruption in 1816). In 1911 the novel was developed as a play for the London stage, handled by someone who knew the Staffordshire Moorlands and the dialect, although it probably didn’t have too long a run in London.

* Sunday Review — “Rose Critchlow is a woman of strongly passionate and sensuous temperament. Unlike many beautiful women, it is not the excitement of general admiration, the winning of open homage [that she wants, but rather …]

* Staffordshire Sentinel — “The book is a very thoughtful and artistic novel. […] The author describes two widely different aspects of life with skill and understanding. Mr. Kineton Parkes knows the country in the neighbourhood of the Dove and its curious tributary the Manifold with a thoroughness which is only born of a deep and affectionate interest.”

* The Westminster Review (1908) — “Potiphar’s Wife by Mr. Kineton Parkes, is, without exaggeration, a work of genius instinct with the loves and hates of the dalesfolk.”

* The Lady journal — “A story so powerful, original, so full of vigorous and convincing characterisation and of sheer human interest […] worthy of comparison with Thomas Hardy’s Wessex romances.”

Sadly the novel appears to be utterly lost in terms of ‘online’, though the British Library apparently has a copy, along with the libraries at Oxford and Cambridge.

There was also a North Staffordshire novel called The Money Hunt: A Comedy of Country Houses (1914), which was distinctly more cheery than the tragic Potiphar’s Wife…

“The Money Hunt is one of the last the author wrote before leaving the moorlands of North Staffordshire for Devonshire. The scenery of “The Money Hunt” is that of the moorlands, as was that of Mr. Parkes’s previous novels, full of excellent humour and with illustrations.”

This blurb assumes that his novel The Altar Of Moloch (1911) was also set in the Moorlands. Despite its gruesome title it was apparently not supernatural, but rather “an account of the musical temperament”. The Westminster Review called it…

“a story of four men and a maid, Beautiful Vaudrey Woodrolle who is the only daughter of a ‘cello-playing village schoolmaster. Her wonderful voice so much impresses the Lady Bountiful of the village that she persuades Mr. Woodrolle to send his daughter to Madame Andreini …”

His Moorlands novels are sadly forgotten and unavailable, and if he is remembered today it’s by academics as a Ruskinite and writer of the 1920s on the sculpture and sculptors of the time. His main output was:

Shelley’s Faith: Its Development and Relativity [1888]

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement (non-fiction) [1889]

The Painter-Poets (Editor) (non-fiction) [1890]

The Library Association In Paris (non-fiction) [1893]

The Sutherland Binding (non-fiction) [1900]

A Guild Of Cripples (poetry and short stories?) [1903]

Love a La Mode: A Study in Episodes (short stories on the philosophy of love) [1907]

Life’s Desert Way (novel) [1907]

Potiphar’s Wife (novel) [1908]

The Altar Of Moloch (novel) [1911]

The Money Hunt: A Comedy of Country Houses (novel) [1914]

Hardware. A novel in four books (modernist novel?) [1914]

Windylow (novel) [1915]

Sculpture Of To-day (non-fiction, 2 volumes, third volume did not appear) [1921]

Mystery Of Chinese Art (non-fiction) [1929]

The Art Of Carved Sculpture (non-fiction) [1931]

He probably also has a number of uncollected essays on sculpture and sculptors, in art journals such as Apollo.

He was also a magazine editor. Kineton Parkes was editor of the illustrated journal Comus (1888-89). Then while at Leek he was tapped as editor of the short lived Library Review (1892-1893), which rather ambitiously aimed to track and briefly review the entirety of the torrent of new books then being produced. One has a vision of wagon-loads of books being carted to Leek from London on a weekly basis. He was later assistant editor and then editor of the monthly Igdrasil: the Journal of the Ruskin Reading Guild.

Phil Dragash’s unabridged The Lord of the Rings.

Superb work, which I’ve now heard all the way through several times. An unabridged reading, with full-cast voices done by an outstanding verbal mimic and actor, expertly melded with the movie’s music and sound FX from the movies and public-domain sources. Can one man do all the voices? Yes, he’s a natural prodigy and he does so with the greatest of ease — imagine ‘Mike Yarwood, trained by the RSC’. With a little help from the examples of the movie voicework, all the voices and accents are also just as you’d expect them to be. Even Bombadil and Gollum.

I can’t link to it here, but if you know what you’re doing with .torrent files and torrent software like qBittorent, search: dragash “2013-2014” 192kbps limetorrents Hint: the Yandex search engine doesn’t censor torrent results like the others. Or if you use Tribler, try just “Dragash”. This search should land you somewhere near the last available version, the one in which Phil had gone back and tidied up some errors of delivery in the early chapters and given us the full uncompressed edition. “Uncompressed” means that 3.9Gb is the size you want.

Bear in mind that you’ll need to own the extended-cut DVD movie trilogy of The Lord of the Rings, the book itself, and the official soundtrack album, to legally download this outstanding free non-profit fan-work. If you also want all the Appendices read aloud then you’ll also need to buy the official unabridged audiobook reading, when you’ve finished with Phil’s full-cast reading.

Phil’s recording is slightly too sibilant (‘sibilance’) on high-response headphones, so you may want Impulse Media Player which offers a graphic equaliser for reducing treble and boosting bass, as well as a slider to slightly slow down the speed of reading — so you can better savour the text and dialogue. This is one of the great audioworks of our time, as well as running for 48 hours, and so you want to be sure you’re listening to it properly.

Update, 2019: I now recommend AIMP as it’s Windows desktop freeware which does all that Impulse Media Player can, but also has simple and editable bookmarks.

Update 2020: since Summer 2020 Phil Dragash’s marvellous version of The Lord of The Rings is now also on Archive.org, with torrents and in its final 2013-14 version…

* The Fellowship of the Ring. (“A Journey in the Dark” has a small encoding ‘skip’, as does the LimeTorrents version, which cuts a few minutes recounting the discovery of the doors of Moria and the unpacking of Bill the Pony).

* The Two Towers. (There is slight but unfortunate elision in the chapter “The Road to Isengard”. Nothing is missing, but the lack of a 10 second gap and a music-change between “…vanished between the mountain’s arms. // Away south upon the Hornburg…” can be confusing to the listener. Since the same group of beings is being described, but their activities are in different and far-separated places at different times).

Update, 2022: No Hobbit from Dragash, but there is an unofficial unabridged “The Hobbit (Audiobook) – J.R.R Tolkien | Soundscape by Bluefax” at Archive.org since November 2020, inspired by Dragash’s work. With music and FX. Young British narrator, with a facility for acting but not Dragash’s world-class talent as a superb mimic. Like the above Dragash LoTR, to legally download this you will need to already own the official book, audiobook and the movie soundtrack album.

Below is the best AIMP graphic-equaliser setting I can get for good headphones, with speed at 97% and Bass at +33%.

Another local novel, found.

Another local novel, found. A rip-roaring historical adventure novel, set in Staffordshire and the Moorlands in the time of the highwaymen and the Jacobite invasion of England in 1745. George Wooley Gough’s The Yeoman Adventurer was published by Putnams in 1917.

The hero is a young self-educated farmer of Staffordshire, who reads the classics and is a keen angler. Apparently fishing features several times in the book, as the author was an angler, and the book opens with an epic battle with a Staffordshire pike. The Spectator review felt the hero to be rather too worthy to be truly enjoyable, and that many of the other characters were rather stereotyped. But the reviewer approvingly noted the brisk modern language used in the book, in contrast to the creaking thee’s and thou’s and wherefore’s usually found in historical novels of the period.

The author (1869-1943) was the son of a Stafford railway worker. Inspired by reading Adam Smith in his youth, he went on to Oxford to study History. He became a Free Trade economist by day, and a historical novelist in the evenings. Born in Stafford town, as a boy of 12 the 1881 Census finds him living at “12 Mill Bank, St. Mary, Stafford”.

“The most stirring and fascinating romance of recent years” (The Daily Graphic, of The Yeoman Adventurer). A New Zealand soldier’s First World War diary entry recorded of The Yeoman Adventurer, “a fine book – one of the best I’ve had lately.”

There’s also a Project Gutenberg edition online, which might be an easier read on the Kindle than the Archive.org version.

He followed this with a sort of 18th century Sherlock Holmes, in The Terror by Night (1923). ‘The Terror’ is an 18th century highwayman/crime-fighter, who sets out in a series of episodes to right various local wrongs and to solve various mysteries. I would assume a Staffordshire setting, but the details are unavailable. This “series of stories that should carry him into the front rank of contemporary novelists” said The Lloyd George Liberal Magazine, to which Gough contributed economics articles. But The Spectator reviewer was less gushing, with “A good example of the period novel with no pretensions beyond amusement”.

Later came the novels My Lady Vamp (1926), and Daughter of Kings (1930). There are no details of these online, but by the sound of the titles they’re likely to be historical novels. It would be interesting to know if the ‘Vamp’ indicates some supernatural vampire element.

The Folk-lore of North Staffordshire, version 1.4

The Folk-lore of North Staffordshire, an annotated bibliography. A new 1.4 version with six new additions. 20 pages. Please update any local copies you may be keeping.

Legends of the Moorlands and Forests of Staffordshire

Miss Dakeyne, Legends of the Moorlands and Forests of Staffordshire, Hamilton, Adams and Co., 1860.

78-pages, printed in Leek. Retold as reciting verse in the style of the time, with “A Legend of Lud Church” in prose. Staffordshire Poets (1928) was unable to discover her first name, but noted “Her family were silk manufacturers, of Gradbach Mill” and a Country Life article on the district later added that the family had been so since 1780. That may be enough information, for those with access to pay-walled ancestry databases, to identify her by name.

The Reliquary summarised it thus: “The metrical legends are “The Chieftain,” relating to Hugo de Spencer and Sir Swithelm of the Ley, of the time of the Holy Wars [12th-13th century]; “Caster’s Bridge”, a legend of a band of desperadoes [in the Dane valley]; “The Heritage”, a sad tradition relating to an old house; and “Lud Church”, an episode in the Rebellion of 1745.”

By the Manifold River

Folklore and word-lore sections from: James Buckland, “By The Manifold River”, The Leisure hour: an illustrated magazine, 1896, pages 116-120.

Cast as they are in the sluggish backwater of the current of modern progress and enlightenment, it is not surprising to find that the people of this wild part of the North-east of Staffordshire retain some thing of the false beliefs of their forefathers.

Indeed, I was astonished to discover that superstitions have a much stronger hold upon them than they themselves care to admit. They do not speak openly of these things, and only grudgingly when questioned; but some strange old traditions and stories are still whispered about among many of the least educated of the moorland folk.

That belief of a mermaid who dwells in Black Meer Pool, a dreary tarn on the summit of bleak Morridge, across whose dark waters the night winds howl dismally, is widespread.

Moreover, there are to be found in this district those who talk with awe of the spectral horseman who nightly rides from Onecote Bridge to Four End Roads.

At the dread hour of midnight, when cold breezes are sobbing upon the sterile bosom of the drear moor, this phantom, mounted on a snow-white steed, comes rushing past noiselessly, brushing even the garments of belated wayfarers, as he speeds by, arrow-like, and vanishes into the night.

There is a man living at Betterton who firmly believes that his father once rode upon this apparition. He had lingered long over his cups one night at Onecote, and, setting forth homewards, he was persuaded to accept the offer of a mount from a horseman who appeared suddenly at his side.

Hardly was he fairly seated behind the mysterious equestrian, when the snow-white steed, with lightning-like rapidity, rose like a bird into the air.

The next thing the poor mortal remembered was being hurled to the bare earth at his own door, where he was found with a bruised body, his face actually deformed by an expression of supernatural horror.

There is a woman too at Warslow who declares that the spectral rider appeared one wild night to’ her father. Swiftly, yet with no sound of clattering hoofs, the phantom sped past her terror-stricken parent; not so swiftly though, but that the latter had time to mark well the bright stirrups and shining buttons of this thing of evil.

In another quarter it was whispered to me that the dreaded spectre had been seen no less recently than last Christmas; but the woman who hinted at this visitation appeared loth to speak of it. So I did not press her for information.

As regards the first two instances, the man and woman alike meet any doubts of their stories with the unanswerable argument that the thing had been seen and sworn to by their fathers, and that if they are not to believe them, who then are they to believe ?

They admit, however, that both “t’ owd uns wur fond o’ a sup o’ yale.”

The notion, also, that any strange or untoward incident is the work of lightning, or the devil, is still rife among those of these moorlanders who rank lowest in the scale of general intelligence.

[The River Manifold goes underground during parts of the year, sinking near Wetton Mill and emerging at Ilam.]

Four years ago a great hissing sound, proceeding from one of the “sinks” at Wetton Mill, was heard by a chance passer-by. In speaking to this man upon the subject, I endeavoured to extract from, him some explanation for so unusual an occurrence.

“‘Lectricity, Oi reckon,” he said ; but, when I asked him how long the noise lasted, he cried, “Oi didna’ wait to see!” In such tones and gestures as left no shadow of a doubt but that he really attributed the cause of the sound to a very different agency than that of electricity.

Some ten years ago a duck was accidentally taken down in the swirl of a “sink.” After traversing the gloomy [underground] course of the Manifold, it reappeared at Ilam in an almost unrecognisable condition. This incident so worked upon the mind of a soft-headed fellow, who lives hard by. That he at length persuaded himself that where a duck went he could go; and he actually fitted out a tub-like boat, laden with candles and provisions, with the object of setting forth upon a voyage of discovery into the cavernous depths of the earth.

Fortunately, before going very far down stream, the crazy boat capsized, and the poor man was nearly drowned — a circumstance which considerably damped his zeal as an explorer. He is still of the opinion, however, that, with a properly constructed craft, the underground passage might be safely made.

One of the Moorlands underground rivers, represented in its diving and surfacing on a 1622 map by a man.

[…]

No iron rails [railways] have as yet taken the place of high roads, and new ideas reach them but slowly. In consequence, the belief that “t’ owd fashont ways are t’ best” still obtains amongst them, and they exhibit, in their ways of speaking and acting, much that is primitive and pleasant. The rude picturesqueness of their whitewashed cottages is but an outward presentment of the old-world aspect within. In some instances the pump which supplies the house hold with water stands in the centre of the kitchen; while in every sitting-room there hang from the walls rows of fire-irons and quaint old-time steel and brass utensils — all bright and clean. “Grand-feyther’s and Grandmother’s” warming pans, covered with snow-white cases of crochet-work, keep company with the “slice” and “spriddle” — instruments used in baking “pikelets” and a species of oatcake which forms the staple food of the people of the district. Upon the shelves there is usually a generous display of pewter plates and antique crockery, while old oak furniture — valuable, too, some of it — is plentiful. Everywhere in the cottages of these moorlanders there is a homelike air of cosiness and comfort.

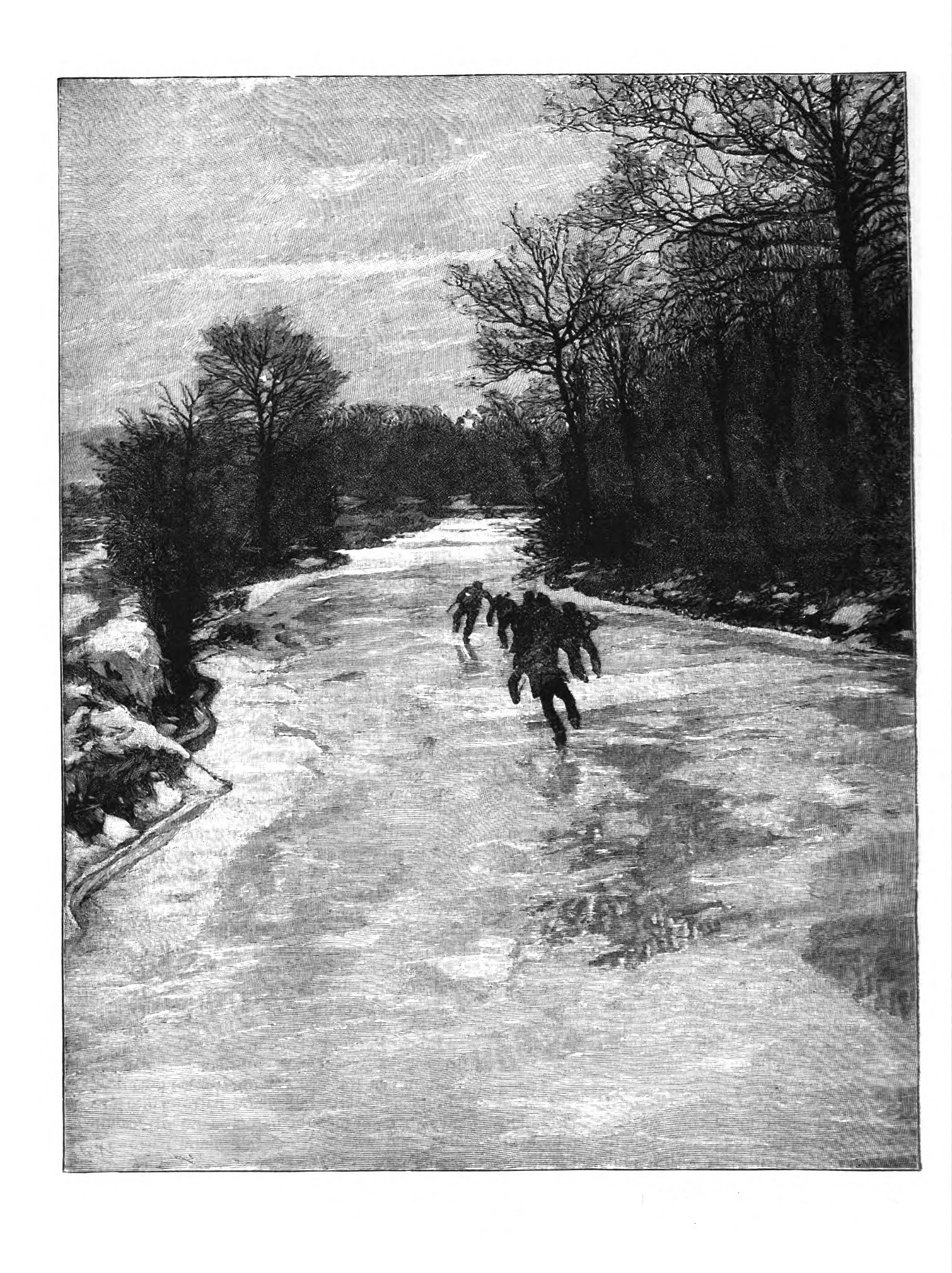

Boys skating on the frozen river, an illustration accompanying “By the Manifold River”, The Leisure Hour, 1896.

Boys skating on the frozen river, an illustration accompanying “By the Manifold River”, The Leisure Hour, 1896.