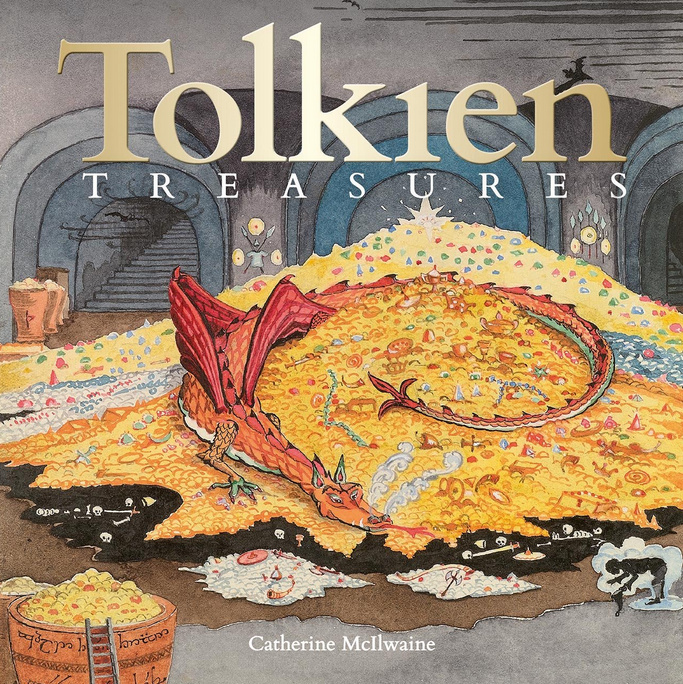

I made an interesting and expenses-paid trip to Oxford today, for the Tolkien exhibition. On arrival I was glad to be able to thoroughly peruse the two new Tolkien books. The bookshop there had open inspection copies. The small £12 paperback, which I thought I wanted, proved only to be a cut-down of the full £25 ‘book of the exhibition’.

Thus I came away with the big £25 paperback version (above), and perused it on the train home to Stoke. I’m already very pleased with it, even on ‘a first flip’ and without the good reading-glasses. The book is almost as good as seeing the exhibition itself, I’d say, if you can’t get there. More so in many ways, because it’s fairly dark in the gallery for archival reasons, and no photography is allowed. Plus it was also very crowded (caused by people lingering, without being ushered out, and the next lot of people coming in behind). I dodged around and stayed in for about two hours. Excellent, though the religion is of course unmentionable.

Curiously Amazon UK only has the hardback of the £25 book. And they mis-state the page-count as 288 pages. It’s actually a hefty 416 pages, not including fold-out card covers. I’m assuming here that the Bodleian Library are not selling some super-sized special edition that’s only available in their shop.

Anyway for the edition I had… lovely paper, great design and printing, though I felt it was too often ‘padded’ in terms of the layout. I could have cut it down by 24 pages, with no loss of anything except pointless empty white space, and saved a few trees.

It was fascinating to see the size of certain things in the exhibition, including the “Book of Ishness”. I saw Tolkien’s painting “Eeriness” (January 1914) for the first time, showing ‘trees with reaching hands’ decades before the Old Forest and Ents. It was also good to finally see his painting “Beyond” (January 1914) in colour. The pyramids are blue and the star is red, not what you might expect of what (in black & white) appears to be a straight desert pyramids scene. Both are in the book in colour. “Beyond” may have been in the exhibition, but if so then I couldn’t find it.

The £25 book also has the first page (1913) of Tolkien’s ‘hours’ logging book’, by which he proved to Edith that he was working hard as promised.

I also saw the frontage of Exeter College, and even stepped through an open gate-door and thus saw the lawned quadrangle for a minute before the security guard appeared. Sadly the around-the-corner doorway to the Fellows’ Garden was as close as I got to the garden, though one could just about see the trees.

The Museum of the History of Science was also visited, in terms of the ground floor and upper floor permanent exhibitions (the temporary political shows in the basement were skipped). I was pleased to see they allow non-flash photography (a policy nowhere stated on their website). I got a couple of nice macro pictures with my pocket digicam (stabilised by slightly resting the lens rim on the glass case, no flash)…

Astronomical Compendium, by Humfrey Cole, London, 1568 (Inventory Number: 36313, Museum of the History of Science, Oxford).

And they had a loan of the late Danish clogg almanac, which makes an interesting comparison with the Staffordshire Clogg Almanacs I’ve previously blogged about here…

All three Oxford pictures in this particular blog post are placed under Creative Commons Attribution.