From the Trent Walk pottery in Stoke, apparently from the 1960s.

Monthly Archives: September 2017

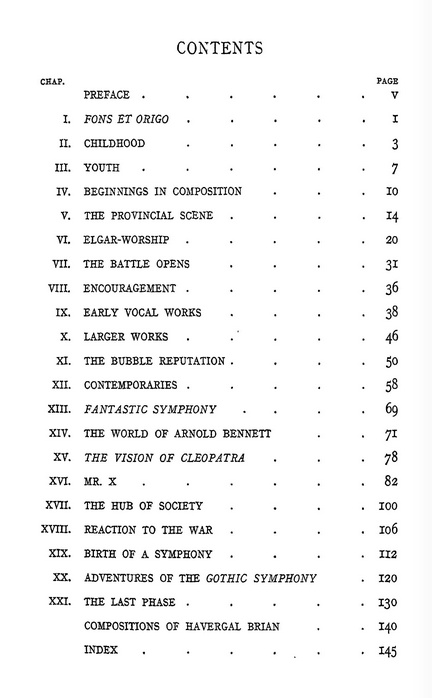

Ordeal by Music

Now free on Archive.org, a 1947 biography of Stoke-on-Trent composer Havergal Brian, Ordeal by Music, from the Oxford University Press.

The Contenders

John Wain’s novel of the post-war ambition and careers of two men, The Contenders (1958) was made into a 1969 ITV drama “set in the Potteries”. 4 x 60-minute episodes according to IMDB. It seems likely that the tapes have not survived, but I wonder if the scripts are still around?

Walker Scott

A name new to me, Walker Scott, oil painter the North West and North Staffordshire.

Charles Dickens in Staffordshire

Charles Dickens visits the Potteries in the early 1850s…

PUTTING up for the night in one of the chiefest towns of Staffordshire, I find it to be by no means a lively town.

I have paced the streets and stared at the houses, and am come back to the blank bow window of the Dodo [Inn]; and the town clocks strike seven. I have my dinner and the waiter clears the table, leaves me by the fire with my pint decanter, and a little thin funnel-shaped wine-glass and a plate of pale biscuits – in themselves engendering desperation.

No book, no newspaper! What am I to do?

The Dodo Inn was actually a lightly disguised name for the Swan in Green inn, Gate St., Stafford. Apparently he merely visited a small bit of the Potteries for part of a day, taking the train from Stafford then a tour of a pot works in Stoke, though he managed to get a long article out of it. The tradition obviously started early, of a London journalist spending a few hours here and becoming an ‘instant expert’ on the district.

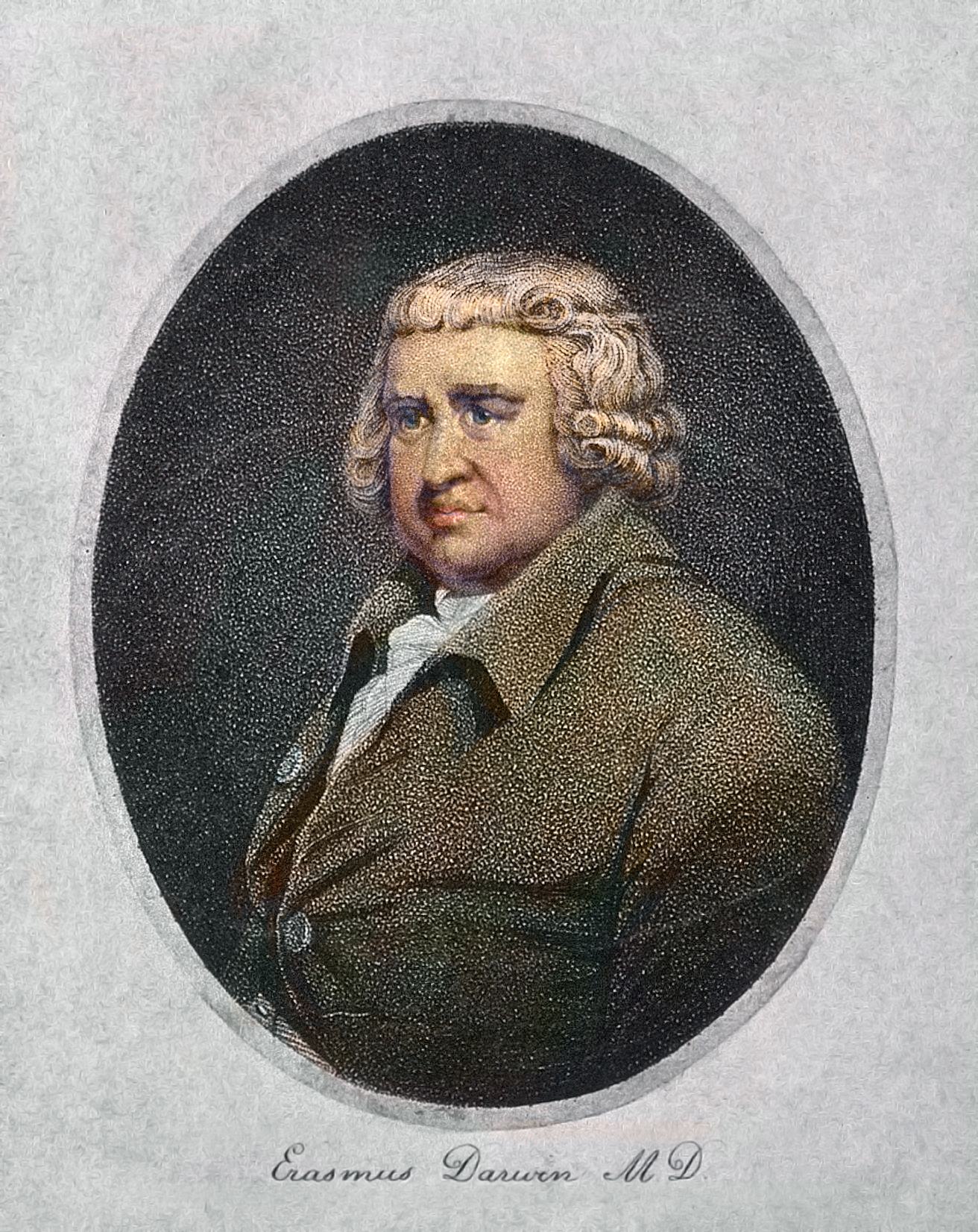

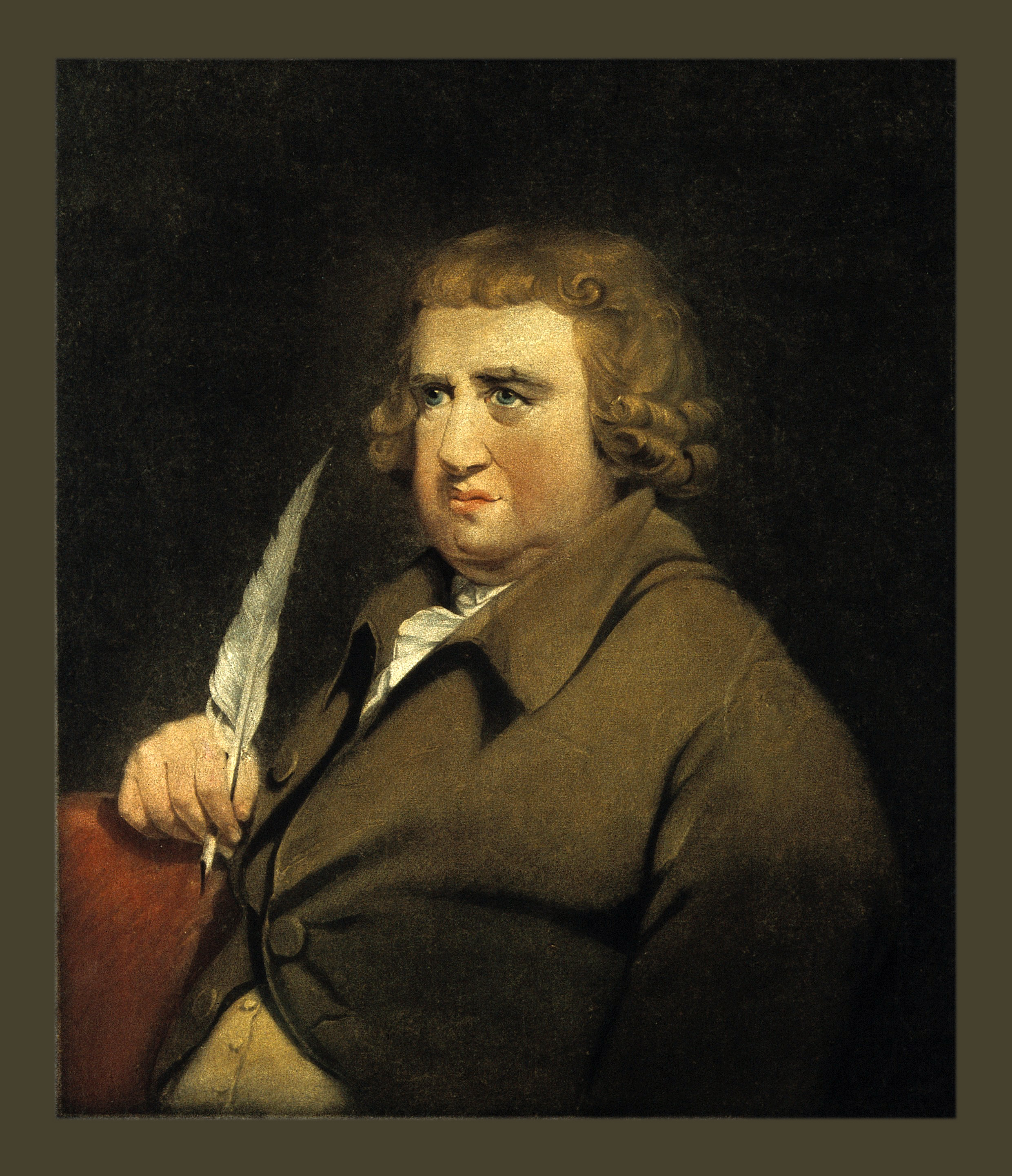

Portraits of Erasmus Darwin

Found: three more novels set in Stoke

I’ve found another three novels set on Stoke-on-Trent.

1) Annie Keary’s children’s novel Sidney Grey: A Tale of School Life (1857), written while raising her children in Trent Vale. Her fiction was well regarded, and the survey book Masterworks of Children’s Literature states the novel was written for her own children and… “dealt with their [north] Staffordshire region and its brick kilns”. The novel was also a “picture of grammar-school life” in the 1850s, with a disabled boy hero. I’m guessing that the school would then have been in Newcastle-under-Lyme, and that the novel drew its impetus from the tensions between school life and life in the brickyards. The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English calls it a “notable children’s book”. For some reason there’s no free copy on either Archive.org, Hathi or Gutenberg.

Update: there was also a later sequel, now online.

2) Cedric Beardmore‘s Dodd the Potter (1931) has an embossed board cover that “depicts an industrial building with chimneys” according to an unillustrated record page for the V&A collection. The novel is apparently a frank Potteries coming-of-age story with what were — in those days — some titillating aspects. A syndicated review in an Australian newspaper remarked…

“Dodd is an employee at a pottery. So are some of the other people — most of them in fact — and their life story, if it is correctly shown by the author is suggestive of curious social relationships in the well known ‘five towns’.”

Beardmore was a Stoke lad, so it was evidently drawn from life, or perhaps life as he would have liked it to be. Arnold Bennett was the author’s uncle, though the novel was written without Bennett’s help. After the war Beardmore went south and into children’s comics. He wrote at least one Dan Dare story for the famous Eagle comic of the 1950s, but his mainstay was writing Belle of the Ballet for Girl comic (the girls’ equivalent of Eagle).

3) Under the pseudonym ‘Cedric Stokes’ Cedric Beardmore also published a historical novel titled The Staffordshire Assassins (1944), set around Bucknall in the 19th century. The Sydney Morning Herald review stated…

“This strange story of an ancient family and a band of renegade monks depends for its interest upon a macabre atmosphere and psychological abnormalities.”

He wrote many other popular novels, and it’s possible that some of those also draw on his life in Stoke-on-Trent.

The Microcosm

“IN the autumn of the year 1765 the ladies and gentlemen of Chester and the country round about were in a state of great excitement over the Microcosm, a mechanical exhibition of moving pictures. The movements of the figures, both men and animals, were considered highly ingenious, and the various motions of the heavenly bodies were represented with so much neatness and precision that the gay life of the city was almost suspended, while the exhibition was crowded day after day by the nobility and gentry, who could talk of nothing else for weeks.” (from Doctor Darwin, 1930, by Hesketh Pearson)

Clocks in the British Museum (1968) states… “‘the microcosm’ was made by Henry Bridges” and suggests it was “probably finished shortly before 1734.” By the time it reached Chester the Microcosm had then been on the road for some years, visiting Lichfield among other places. The poet Pope wrote a poem its praise in 1756. It was made by… “the eldest son of Henry Bridges of Waltham Cross, architect and builder of the amazing Microcosm Clock.” Very little more can be found about it, if a quick search of Google Books and Google Scholar is anything to go by.

Sir Gawain as an audiobook: the options

I see that the 2006 BBC Radio adaptation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is now free on Archive.org. At the climax of the story Gawain crosses from Cheshire, somewhere around Congleton, rides past Leek and then takes a road up into the Staffordshire Peak District, so in part Gawain is a local tale and the poet was a man of the northern part of the West Midlands. Be warned that the BBC’s reading was from the Simon Armitage ‘modern vernacular’ version, and was radically abridged down to just 42 minutes. Still, it’s probably a good introduction for older children who might not listen to anything longer and who would be confused by thee‘s and thou‘s and other archaic language.

In comparison other free readings run far longer, usually around 2.5 hours. Such as the best Archive.org/Librivox version which is Tony Addison’s steady reading of the early translation by Jessie Laidlay Weston. Hers was a spritely early translation published at the turn of the 20th century, and was only very occasional sprinkled with thou and ye, quoth and bade.

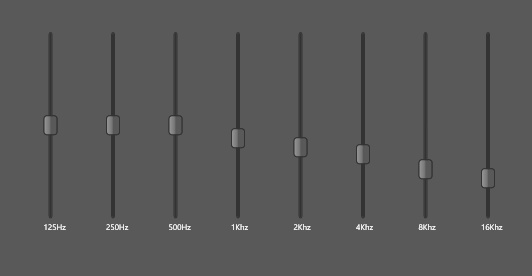

Tolkien’s translation, probably the best available in terms of a listening experience despite also having many thee‘s and thou‘s, is available as a 2006 HarperCollins audiobook. It’s professionally read by Terry Jones in around 2.2 hours, not including Tolkien’s 15 minute scholarly introduction. Jones sounds a little fast and sibilant/breathy. For me his reading works best when played in the free Impulse Media Player, which on a desktop PC allows real-time pitch shifting and other tweaks. Slow him down by -10, and use the following graphic equaliser settings, and see if he improves for you…

We need online map services to accept OS grid numbers

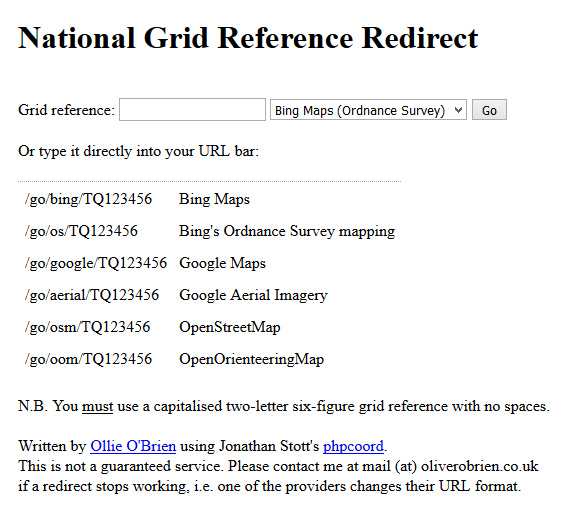

It’s surprisingly difficult to find any online map service which accepts Ordnance Survey grid references, even the OS-based footpathmaps.com which one of the quickest-loading map services in the UK. Surely the UK government should require that the OS licence a grid reference option ASAP, to all the major map services? A little drop down box, input your OS GR number… and off you go. How difficult can it be?

Thankfully that’s exactly what the National Grid Reference Redirect has made. It’s blissfully simple and works. Sadly it doesn’t speed up the incredibly slow-loading and generally spam-filled online map services, but it works with Google Maps and Bing Maps and more.

You just have to make sure you use the format SJ882359. That means if you have a more precise four-number grid reference like SJ882?359? then you’ll need to lop off the last ‘?’ number in each block of four.

In future it would be great to see it work with the excellent footpathmaps.com. The other great UK mapping service maps.nls.uk can already handle OS grid reference input, although only for historic maps, and it’s often as slow as all the others (bar footpathmaps.com).

Update: footpathmaps.com no longer offers OS maps.

“Stoke? Nope, it’s nowhere near us, honest…”

Why does the Staffordshire County Showground website (just east of Stafford) completely ignore Stoke-on-Trent? The distance in miles on the ‘Location’ page makes no indication of how near it is to the city. And according to a Google site: search the nearest the website as a whole comes to mentioning the city is that it has a tickets agent at John Rice Motors at Blythe Bridge, and that one old event had “guest speakers from the National Farmers Union, Stoke-on-Trent and Staffordshire LEP and the Country Land and Business Association”. That’s it.