Tolkien Gleanings #28

* Newly and freely online in 2022, the 2014 Australian PhD thesis Imagined worlds: the role of dreams, space and the supernatural in the evolution of Victorian fantasy. The new…

“concept of hyperspace was a fundamental and sustained aspect of the British imagination” [and its deep and serious exploration then contributed to fantasy’s acceptance as] “an appropriate vehicle through which to explore the possibilities and conditions of other worlds”.

As in his medievalism, Tolkien’s thinking on time and dreams must have been entangled with this stream of culture. We have to remember that Victorian ‘reconstructed’ medievalism and proto-fantasy had a profound effect on many of Tolkien’s teachers, and later on various Edwardian youngsters (such as himself) who re-discovered it. There was also a later vogue for the old heroic romances among the more romantic soldiers who fought in the First World War, and I would imagine that some of the scientific romances (e.g. the early Wells) also had a re-reading at that time.

* In the Mail this week, a short article on a frosty walk in the Cotswold uplands. The writer goes “Following in the footsteps of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien”…

“It was the winter of 1945. They’d travelled with a group of friends from Oxford, where both were dons, to have a ‘Victory Dinner’ at The Bull Inn in Fairford to mark the end of the Second World War, and spend a few days on their passions: beer and talking.”

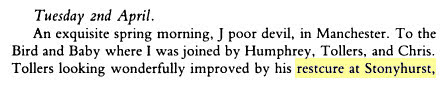

Also walking, pre-Christmas 1945. The backdrop to this was war-time food rationing and overwork and exhaustion by the war’s end. Tolkien’s health and home-life were both affected and imminent for Tolkien, when at Fairford, was a doctor-ordered “restcure”. The Chronology has “after Christmas his health gives way”. But by the following 2nd April 1946 a friend noted of him… “Tollers [Tolkien] looking wonderfully improved by his restcure at Stonyhurst” (from The Diaries of Major Warren Hamilton Lewis, 1982).

This comment adds a bit more to the ongoing mini-saga of Stonyhurst, recently mentioned several times in Tolkien Gleanings. Tolkien “stayed at a guest house in the grounds” and the guest-register shows him there “21st March to 1st April 1946”, which helps confirm the above diary entry about the “restcure” he took there. It’s strange, how seemingly unconnected bits of news can link up like that. So it can now be seen that it wasn’t just any old short break with his son at Stonyhurst. Rather it was a vital attempt at recovering his health and equilibrium, at a very difficult time both personally, creatively and nationally.

* In 2020 Christopher Armitage remembered how J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis influenced his 53-year academic career”. In the early 1950s Tolkien’s…

“lectures were always full of students [despite his being hard to hear if one was sat on the back-row. He was approachable…] Class had ended after discussing the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. “There is a refrain in that poem when characters say ‘barlay may’” Armitage said. “It’s from French, ‘parlez moi’ anglicized, and used when you’re calling for a power play or a comment. So the action is suspended.” He told Tolkien that he and childhood friends used the expression ‘barley me‘ to ask for a time-out while playing soccer or cricket in their neighbourhood street. “Tolkien was quite fascinated and asked where we played games, and I explained to him it was where I grew up in Sale, Cheshire [now south Manchester], the county south of Lancashire” Armitage said. Jotting the expression in a notebook, Tolkien insisted that Armitage provide the street address. Armitage does not know if Tolkien used the reference in a scholarly work.

Yes, I see the old dialect books confirm ‘barley me’ as a Cheshire saying. This must then be a relative of the Birmingham ‘bagsy me’. The first child who thinks to make such a bagsy statement effectively suspends any tedious and play-delaying squabble, by claiming the right to ‘go first’ in a game. Or to be the first to try a new toy, be first in the bath, to get the front rather than rear seat in a car, or get the first sausage out of the pan, etc. It might also excuse one from starting a game as IT, as in “bagsy not IT” just before a playground game of tag.

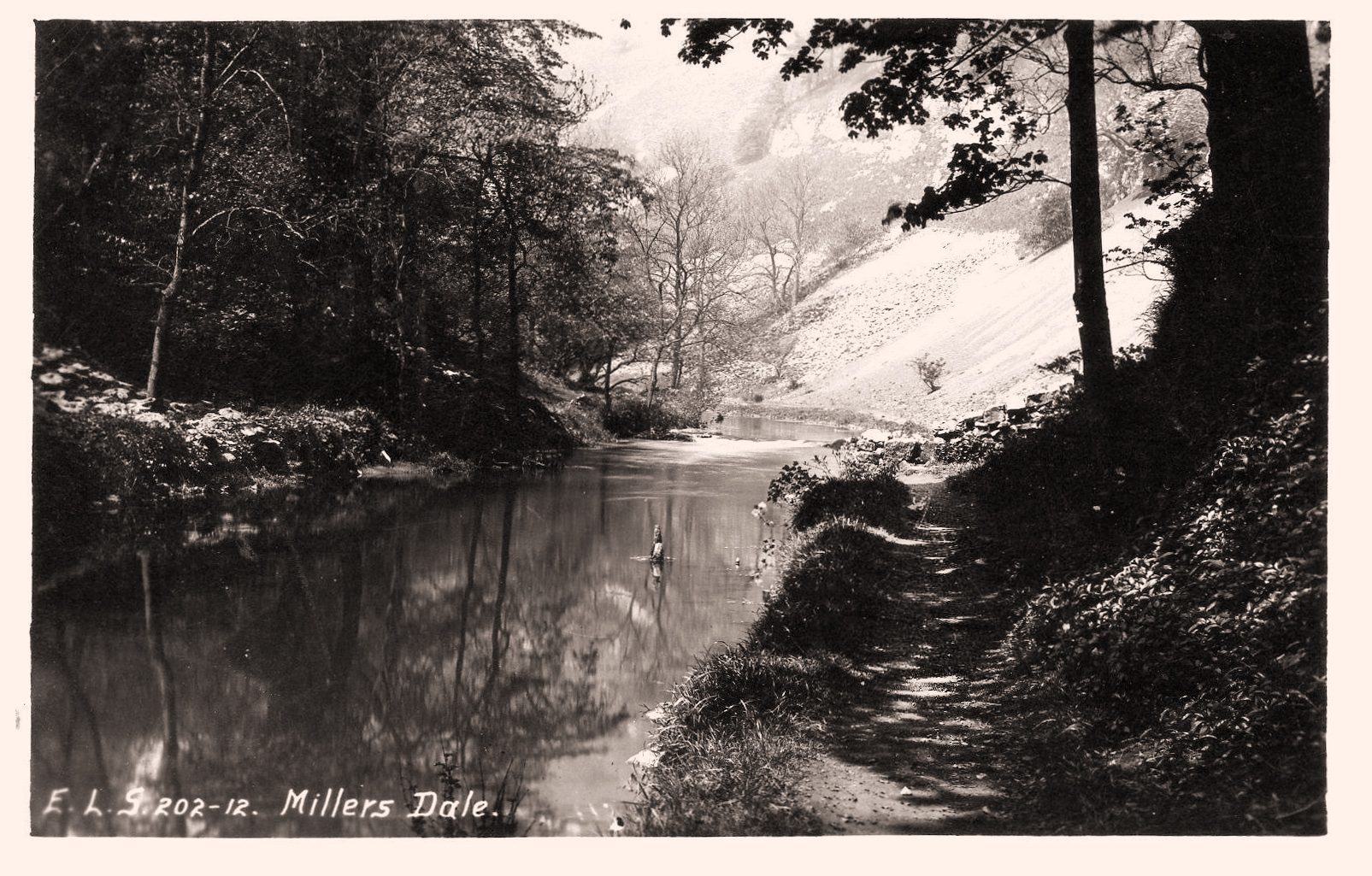

Armitage’s reminiscence also shows that in the early 1950s Tolkien was still conveying the idea of Gawain being ‘of Lancashire’ rather than (as we now know) further south in North Staffordshire. Even though Mabel Day, who Tolkien knew at this time via his involvement with the Early English Text Society and her editing of Sir Israel Gollancz’s Gawain, had in 1940 publicly and prominently suggested Wetton Mill in North Staffordshire. Day had followed Serjeantson’s 1927 suggestion of “the western part of Derbyshire” (adjacent North Staffordshire) as the home of the Gawain-poet, and Bertram Colgrave’s 1938 suggestion of North Staffordshire as a location for Gawain’s Green Chapel.

* And finally, ticket booking for The Tolkien Society’s Oxonmoot 2023 is now open, with an Early Bird discount available into February.