Author Archives: futurilla

More on Tolkien’s Library

A detailed response to the criticism of the new book Tolkien’s Library, from the author.

Half of it is a usefully detailed investigation into Tolkien’s likely input into the Davis revision of the Tolkien & Gordon edition of Gawain.

Tolkien and borders

Some interesting sounding papers in a Tolkien session planned for the Leeds International Medieval Congress 2020…

Borders in Tolkien’s Medievalism III.

* Boundaries and Marches: Marked and Unmarked Edges in Tolkien’s Maps, by Erik Mueller-Harder, Independent Scholar.

* The Walls of the World and The Voyage of the Evening Star: The Complex Borders of Medieval Geocentric Cosmology, by Kristine Larsen, Central Connecticut State University.

* Time-Travel, Astronomy and Magic Mirrors: The Borders between ‘Reality’ and ‘Otherworlds’ within Middle-earth, by Aurelie Bremont, Sorbonne Universite Paris.

Have a cow…

A Wulfhere novel

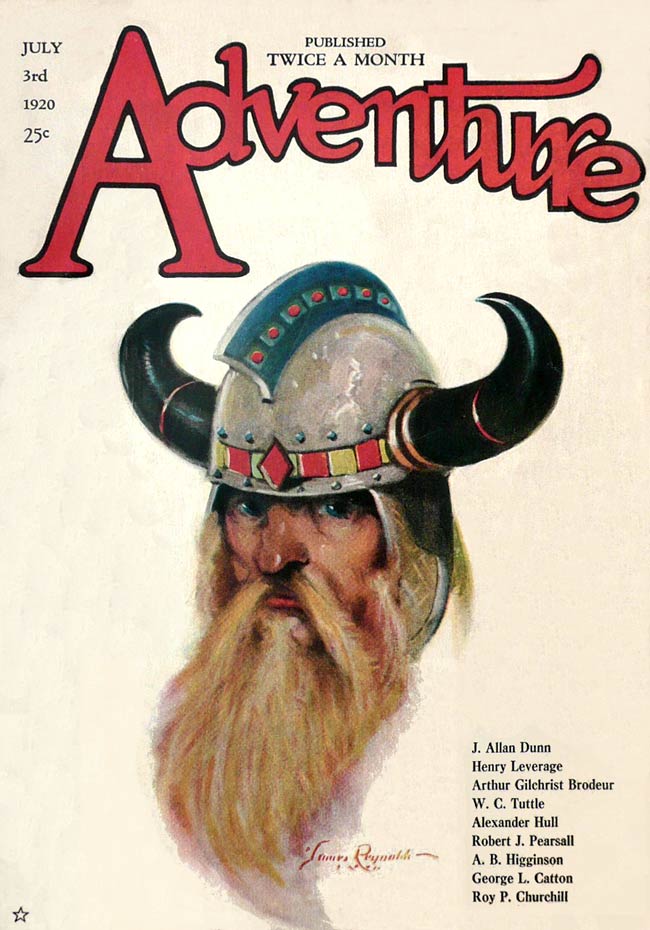

A historical novel reprint is coming soon from publisher DMR. It’s Wulfhere (1920) by A.B. Higginson. The name of King Wulfhere will be familiar to those who know the local history of early Mercia, and who have even perhaps visited his hill-fort between Stone and Stoke. The novel vividly tells his ‘life story’, such as it can be known or inferred. The novel originally ran as a serial in the top-selling Adventure magazine in the USA but was not subsequently collected as a book. Said to have been an inspiration for Robert E. Howard, of Conan fame.

The new single-volume 2019 edition is not yet listed as a page on Amazon or DMR, but is said to be due in a month or so. Update: it’s here.

The light of Day

I’ve now seen the 10% free sample for David Day’s new A Dictionary of Sources of Tolkien. All was going well until I got half way through the ‘A’s and hit “Alcuin of York”. Alcuin as “comparable” to Gandalf? After that I began to spot many “is comparable to” and similar broad statements. While I found some entries informative, a few seemed to be grasping at straws. “Bard the Bowman” for instance, is deemed to be modelled on the Greek Apollo. Really? I also sensed a slight pro-Christian and pro-King Arthur tilt on some of the entries, more so than might naturally to be expected to come from dealing with Tolkien material.

The book’s introduction states it was written for the “general” reader, and as such it appears (at least in the ebook) to feel free to dispense entirely with footnotes and references. We are left to wonder, for instance, about “Alfirin” (Simbelmynë) when it is stated that… “As a flower, Tolkien himself compared it to the anemone” [as understood by the ancient Greeks], in terms of where to find the reference for that. The Tolkien Letters offer only…

“I have not seen anything [i.e.: in either life or botanical reference books] that immediately recalls niphredil or elanor or alfirin: but that I think is because those imagined flowers are lit by a light that would not be seen ever in a growing plant and cannot be recaptured by paint. Lit by that light, niphredil would be simply a delicate kin of a snowdrop; and elanor a pimpernel (perhaps a little enlarged) growing sun-golden flowers and star-silver ones on the same plant, and sometimes the two combined. Alfirin (‘immortal’) would [in name-translation] be an immortelle [i.e. flower that does not loose its colour when picked and dried], but not dry and papery [as a dried immortelle is]: [in its growing form] simply a beautiful bell-like flower, running through many colours, but soft and gentle.”

The Flora of Middle-earth has it that… “Tolkien considered it to be an imagined kind of anemone” but the reference there is to “Nomenclature of the Lord of the Rings” section in the 2005 Reader’s Companion. The Tolkien Gateway entry on “Simbelmynë” (Alfirin) also has this claim and reference. One then needs to be savvy enough to know that the Reader’s Companion and the Reader’s Guide are quite different reference books by the same authors, published just one year apart, and that their shorthand titles are easily confused. On consulting the correct book, we find Tolkien’s guide to his overseas translators offering…

“an imagined variety of anemone, growing in turf like Anemone Pulsatilla, the pasque-flower, but smaller and white like the wood anemone. … the plant bloomed at all seasons [yet] its flowers were not ‘immortelles’ [for the nature of ‘immortelles’, see the Letters quotation above].

Thus Day’s conflation of Tolkien’s advice to his translators and the outlining of a Greek myth…

“As a flower, Tolkien himself compared it to the anemone, which the Ancient Greeks associated with mourning: when the goddess of love Aphrodite wept over the grave of her lover Adonis, her tears turned into anemones.”

… does not support the run-on implication that it was Tolkien explicitly making the link with the myth. Also, the myth as given seems a little ‘off’. Since Ovid (Metamorphoses X) has it that the mythic flower in question is purple, not white, and made from the mingled “nectar” of Aphrodite and the turf-splashed blood of Adonis. Nor is there a “grave” in Ovid, as Adonis is a shepherd-boy and has been gored in the leg by a boar, hence his blood on the close-cropped turf. Later Bion of Smyrna was more coy, and in his telling of the tale he turned the implied-sexual “nectar” into “tears”.

Anyway, the free 10% for Day’s A Dictionary of Sources takes you to the ‘Be..’ entries, and you can make your own judgements. But on the basis of their being enough of interest in the sample, I’ll be looking for a paper copy when the price gets low enough — as it surely will due to the likely sales levels. But then I’ll be marking it up with a scoring system for each entry. Which means that I need the paper edition. Another reason to prefer paper here is because the ebook appears to lack any linked table-of-contents for the main entries. Paging through its entries on a Kindle 3 is thus a pain. Possibly this is remedied by a hyper-linked index at the back, but I wouldn’t like to spend £17 on finding out that there isn’t one.

A local ghost story for Halloween: “Crewe”

Who knew? One of Walter de la Mare’s best short ghost-stories is “Crewe”, set locally in Crewe railway station.

When murky winter dusk begins to settle over the railway station at Crewe its first-class waiting room grows steadily more stagnant. Particularly if one is alone in it. The long grimed windows do little more than sift the failing light that slopes in on them from the glass roof outside and is too feeble to penetrate into the recesses beyond. And the grained massive furniture becomes less and less inviting. It appears to have made for a scene of extreme and diabolical violence that one may hope will never occur.

Available free at Archive.org in text. Not free in audio, except in abridged form.

It was published 1930 in his collection On the Edge: Short Stories, and thus we might plausibly assume it to have been written in the last years of the 1920s.

Two new books on Tolkien

Two new Tolkien books seem of possible interest to me, in the Amazon forward listings.

A Dictionary of Sources of Tolkien is from David Day, the prolific and unofficial encyclopaedist of Middle-earth. It looks interesting enough to sample the free 10% on Kindle, when it sees publication in a few days. After the abundant illustrations are subtracted it looks to have perhaps 350-pages of commentary on sources. At 544 pages in total, the 10% sample of the book should be enough to make a judgement on its usefulness and depth or not.

Also of note is a new French book La Terre du Milieu: Tolkien et la mythologie Germano-Scandinave (trans. Middle-earth: Tolkien and German-Scandinavian mythology). A translator is listed, which led me to discover that it’s a French edition of Rudolf Simek’s 2005 200-page German book Mittelerde: Tolkien und die germanische Mythologie. That led me to a preview of the Contents page in German on Google Books, which could then be run through Translate thus…

1. J.R.R. Tolkien: The medieval researcher as a novelist

Tolkien’s life and scientific career

The novelist

Tolkien and the Old Norse literature

The songs of the Edda and the prose Edda

Old Icelandic sagas

The Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus

2. Geography and geographic names of Middle-earth

Cosmography and Cartography

Tolkien’s World: Middle-earth

Otherworldly realms

Waste lands, wastes

Mountains and forests

Water and sweetbreads

Landscapes and parts of the country

3. Persons of Scandinavian origin

Dwarfs (dwarves) in the Edda and Tolkien

The Kings of the Rohirrim and their ancestors

The Hobbit families

Other influences from Old Norse

4. Odin’s appearance

Gandalf and Odin

Saruman and Odin

Sauron and Odin

Manwë and Odin

5. Natural mythological elements

Who is Tom Bombadil?

Ents and Entfrauen

Beorn, the Gesrairwandler

6. The friendly members of the lower mythology

Hobbits

Dwarfs (dwarves)

Elves

Wasa (Woses)

7. The menacing powers of lower mythology

Orcs

Goblins, Bilwig (goblins)

Uruk-hai

Trolls

Giants

Balrogs

8. Mythical animals, mythical animals and animal monsters

Dragon and Dragonhunt

Eagle

Wolves and wargs

Werewolves

Oliphants

9. Runic writings

The variants of Futhark

Tolkien’s creative approach to runes

Dwarf runes and moon runes

Cirth und Angerthas

Symbol-rind Zauberrunen

The runic inscriptions in Hobbit and Lord of the Rings

10. Motifs from the German mythology and heroes of legend

The One ring

The King in the Mountain

The Shadow Army

The Broken Sword

The worship of the gods without a temple

Zahi Nine

Revenants, “Funeral Items” (barrow-wights)

The Earendil myth

High Heights, Thrones (High Seats)

So, to pack that lot into just 200 pages makes it look like a broad survey. A quick search leads me to just one review online, in German. Turns out the author of the book is… “a professor of medieval German and Scandinavian literature at the University of Bonn”. The reviewer notes that… “Very commendable in this context is Simek’s effort to find out which Nordic literature was published and available in the United Kingdom in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when Tolkien was a student and [lecturer?].” Our knowledge here is still somewhat limited (even now, with Tolkien’s Library in print), but the reviewer notes that Simek is not afraid to “speculate” on what Tolkien read and/or knew. The book looks like an interesting overview, but… it’s not in English.

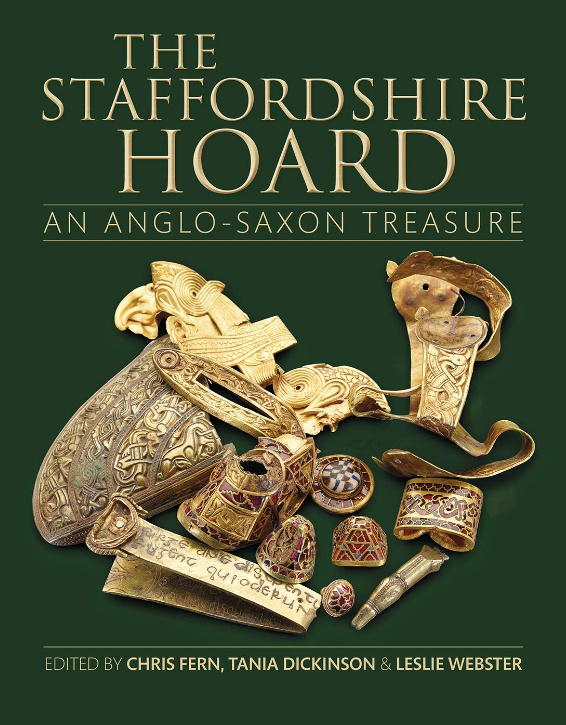

The Staffordshire Hoard: the book

The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure, being the 640-page official Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries. The book was supposed to ship at the end of September 2019, but it hasn’t been getting reviews or a “Look Inside” tab on Amazon. An article in The Sentinel (10th October) suggests why — the shipping date has slipped by over a month…

“This book will be available to buy from 1st November”

Given the dates, it seems to me most likely that the Hoard originated in a turbulent time (655-658) in Mercia. The years between the death of King Penda and early years of the rule of King Wulfhere and his restoration of Mercia. My own working theory would be that it was a purging of ‘tainted’ gold and similar items, by the new King Wulfhere early in his reign. Mostly a purging of items made for Peada and given from Northumbria by Oswiu, items which there had been petty disputes over, or which now was deemed too pagan or which had failed to bring good fortune in battle. By burying it in secret, at more or less the centre of the kingdom as it then was, the items would be deemed ‘cleansed’ and returned to the earth.

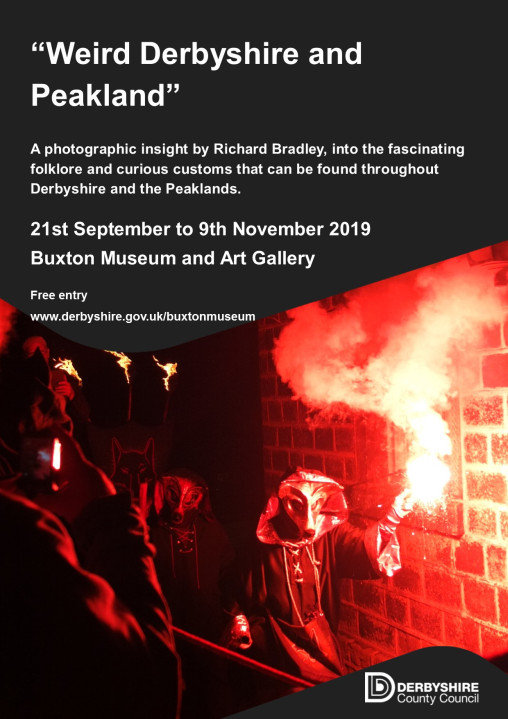

Weird Derbyshire

Weird Derbyshire and Peakland at the Buxton Museum and Art Gallery.

A Midsummer Tempest – a Midlands fantasy novel

The prolific American science-fiction author Poul Anderson also wrote historical fantasy novels. One was even set here in England and had a witty earth-mysteries / dark-faerie twist.

A Midsummer Tempest (1974) is an alternative history fantasy set in an England in which Shakespeare’s Fairy Folk are real and the English Civil Wars are partly an early-steampunk affair with airships. Better, I see it has scenes set in Buxton, the Welsh Marches of Shropshire and Stratford-upon-Avon. There’s even a passing mention of Stoke. A quality local(ish) fantasy novel that I had no idea existed. Who knew?

At just 200 pages it’s not one of those over-padded 1990s/2000s “thick as a brick” fantasy books, either. Nice.

It was nominated for the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel and the Nebula Award for Best Novel. It also won the Mythopoeic Award. And that was back in the 1970s, when awards in fantasy and SF still meant something and had not been hijacked by the far-left.

Gawain walks

Stoke and Newcastle Ramblers are soon to do walks over more-or-less the ‘Gawain country’, which may interest those who have read my recent book on Gawain in North Staffordshire. I’m uncertain if they’re even aware of Sir Gawain but their relevant 2019/2020 walks include, in order of possible/likely Gawain travel…

Danebridge(?)

Mow Cop(?)

Biddulph Moor(?)

Rushton Spencer

Out of Peak Forest

Ecton Hill and the Manifold Valley

Alton Common