At The Potteries Post, Good news: Ten rare paintings of Stoke discovered, to go on show soon in Tunstall in Stoke-on-Trent.

Author Archives: futurilla

New: “With the Night Mail”, annotated edition

My labour-of-love “With the Night Mail”, annotated edition is available now as a .PDF file on the Gumroad service.

This is the best version of the famous “With The Night Mail” (1905), the first ‘hard’ science-fiction story. Still an absorbing and lively steampunk read, today.

Here newly and fully annotated with 4,600 words of precise scholarly annotations. Several important new discoveries are made, including the identity of “little Ada” — she was a real pilot! All four earliest versions have been checked and cross-referenced, and the modern corrupted text has been carefully cleaned. Differences between editions are noted in the footnotes.

There are 145 footnotes in total, explaining the technology, lingo, and places. One footnote even discovers a long ‘new’ section of dialogue about the risk of plague, unseen since the first publication — and never reprinted until now!

This .PDF is thus as close as we will get to a definitive version of the seminal story that launched the entire genre of hard science-fiction, and which had the honour of opening the highly influential Gollancz survey anthology One Hundred Years of Science Fiction (1969).

As a bonus, there are four new full-page colour illustrations including one of “George”. This labour-of-love e-book is 28 pages in total, delivered to you as a .PDF file. It may interest RPG gamers, as well as scholars and readers.

Many have agreed on Kipling as the first true SF writer in the modern sense:

Kipling was… “the first modern science fiction writer” — John W. Campbell, editor of the seminal Astounding magazine and pioneer of hard science-fiction.

What Kipling was doing in “With the Night Mail”… “had never been done before. There is no such subtlety in the contemporary proto-SF of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne. I think we may safely credit him with inventing the style of exposition that was to become modern SF’s most important device for managing and conveying information about imaginary futures”. — “Rudyard Kipling Invented SF!”, by Eric S. Raymond.

“With The Night Mail”… “anticipated the style and expository mechanics of Campbellian hard science fiction fourteen years before Hugo Gernsback’s invention of the ‘scientifiction’ genre and twenty-seven years before Heinlein’s first publication.” Eric S. Raymond, A Political History of SF (2000).

“With The Night Mail” is… “an amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius […] the sort of thing that Verne or Wells would never have dreamed of doing […] Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s.” — Bruce Sterling.

Kipling… “is for everyone who responds to vividness, word magic, sheer storytelling.” — Poul Anderson.

Kipling was… “a master of our art.” — Gordon R. Dickson.

“He was a superb and painstaking craftsman, the most completely well-equipped writer of short stories ever to tackle that form in the richest of languages.” … “”With the Night Mail” is an astounding vision … his influence on 20th century SF writers was probably greater than anyone else’s, except Wells … he was a master at making the fantastic seem credible”. — John Brunner.”

“When you read Kipling, you’re there, [he] builds a total sensory impression that surpasses the language” [which is partly why he will never be taught in schools] — C.J. Cherryh.

“what a good writer he was … the work is superb and he could make words sing. [On looking into the political claims that had dissuaded me from reading him,] I found that most of his supposed sins had been vastly overstated.” — George R.R. Martin.

At SF conventions… “I found that so many SF writers could see his sterling merit that I felt vindicated” [in my early love of Kipling, despite my mundane Eng. Lit. teachers who ignored him] — Anne McCaffrey.

There are two anthologies from science-fiction writers influenced by Kipling. Heads to the Storm: A Tribute to Rudyard Kipling, and A Separate Star: A Science Fiction Tribute to Rudyard Kipling. “Accompanied by introductions [to stories] in which the likes of Poul Anderson, L. Sprague de Camp, Joe Haldeman, and Gene Wolfe describe the impact that reading Kipling has had on their own writing.”

Also, in my new 2022 annotated text I could have mentioned some of the loose predecessors to “Night Mail”, but I didn’t want to speculate too much. I note these here…

1) Possibly Kipling had persevered with trying to fathom Edgar Allan Poe’s rambling “Mellonta Tauta”. A late political satire by Poe, now only comprehensible to those who know the tedious American politics of the period. Told as if letters from a slow balloon voyage around the earth, though there are encounters with faster luxury ‘liner’-like balloons…

“How very safe, commodious, manageable, and in every respect convenient are our modern balloons! Here is an immense one approaching us at the rate of at least a hundred and fifty miles an hour. It seems to be crowded with people – perhaps there are three or four hundred passengers — and yet it soars to an elevation of nearly a mile, looking down upon poor us with sovereign contempt.”

The tedious voyage leads to men struggling to amuse themselves by recalling “the old days” and how things were done then, and hence we get the tortured satire on Poe’s day. Possibly this was uproariously funny to Poe’s magazine readers, but it is almost un-readable now and certainly not the influential precursor to a whole field of later science-fiction.

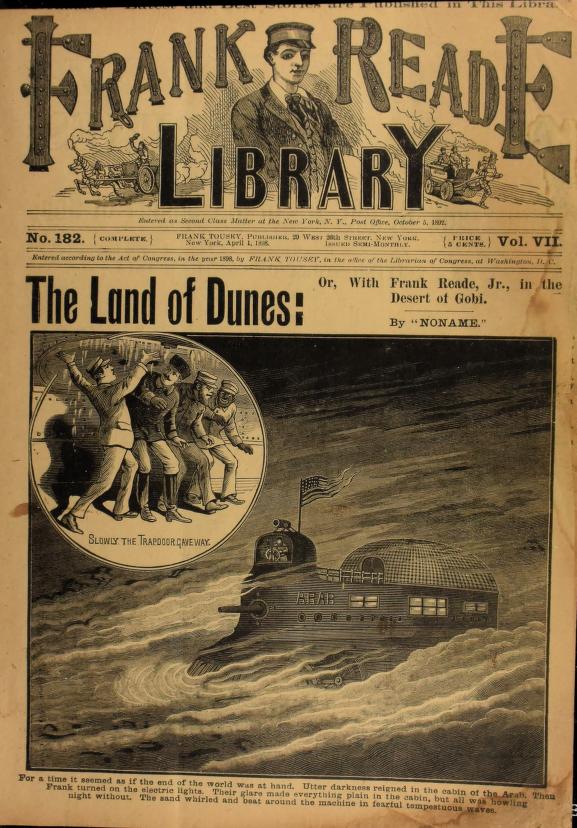

2) I might also have mentioned H.G. Wells “The Land Ironclads” (1903) as having a slim claim to being the first ‘hard’ SF. But I think Arthur C. Clarke was right when he called it “an engineer’s story”, rather than imaginative futuristic SF. The new invention is deployed in the present-day (Wells’s setting is 1903’s cavalry, bicycle, trench and “Howitzer” artillery warfare of the Boer War) to make various political points. His armoured war-vehicles are 80-foot steam-powered metal tanks — and rather akin in shape to the various armoured land-craft that had, for a decade or more by then, been the staple of the American ‘boy inventor’ weekly story-magazines…

Example from 1898. This ‘land ironclad’ is similar in size and design to those of Wells.

Kipling instead imagines a complete distant-future world with multiple interlocking advanced technologies, attitudes, world-system and economies. And he makes it believable and human. He invents or anticipates numerous things that have since come to pass, and does so in a single tale.

3) There’s also a journalistic account that could have influenced Kipling’s “With the Night Mail” prior to 1905. This point has been suggested as such by the author of the free “Night Mail”-based RPG game Forgotten Futures. This short true-life article was Edward John Hart’s “With Her Majesty’s Mails to Ireland”, in The Strand Magazine in April 1895, being a brisk journalistic account of a mail packet journey across the Irish Sea from Holyhead in Wales to Kingstown. This article is now freely online at Archive.org. There is a similar encounter with a dingy tramp steamer, but Hart has him being avoided and gone in a few seconds. There is a similar recounting of shipping lights seen and passed, but such things are to be expected. The mail-ship ‘meets the dawn’ before her arrival. Those are the only similarities I can see. Possibly the general idea of such an account was all that taken by Kipling, if he had even noticed it.

J.R.R. Tolkien: The Art of the Manuscript

Until 23rd December 2022 at the Haggerty Museum of Art in Wisconsin, the exhibition “J.R.R. Tolkien: The Art of the Manuscript”. 147 items on show from two U.S. archives and from Oxford, including… “many which have not been previously exhibited or published”.

Design for a page from the Book of Mazarbul.

MegaTolk

Time for another “MegaTolk”. Newly appeared interesting items on Tolkien that are open and public, since my last round-up in which was back in May 2022…

* Worlds Made of Heroes: a tribute to J.R.R. Tolkien. A complete scholarly ebook in open access, from the University of Porto. Includes, among others…

– The importance of songs in the making of heroes.

– Wounds in the world: the shared symbolism of death-sites in Middle-earth.

– From epic narrative to music : Tolkien’s universe as inspiration for The First Age of Middle-earth: a Symphony.

– Character and perspective: the multi-quest in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

– Geoffrey of Monmouth and J.R.R. Tolkien: myth-making and national identity in the twelfth and twentieth centuries. (Also a useful survey of Tolkien’s West Midlands patriotisms)

– Mythology and cosmology in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

* Song Lyrics in The Hobbit: What They Tell Us (Detects in the lyrics the different relationships that each race has with time).

* “Pearls” of Pearl: Medieval Appropriations in Tolkien’s Mythology. (Excellent study of the likely influence of Pearl)

* The image of the tree as the embodiment of cosmological and solar aspects in J.R.R. Tolkien’s works.

* The Joys of Latin and Christmas Feasts: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Farmer Giles of Ham.

* Medieval Animals in Middle-earth. (Found from 2021).

The Alton boggart

I’ve now seen the new Boggart Sourcebook. The unglue.it aggregator has it and usefully offers a “Save to Dropbox” feature that works in getting the PDF file. The normal PDF download is still not working.

The new book has the usual Kidsgrove boggart article and gives it as a good fully transcribed text…

* ‘Up and Down the Country: Ranscliff’, Staffordshire Sentinel and Commercial and General Advertiser, 6th December 1879.

It also brings to light…

* A newspaper article on a Harecastle tunnel rape trial (Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser, 16th August 1843, page 4), which shows the lore was well-know to boatmen in 1843.

* Leese, Philip R. The Kidsgrove Boggart and the Black Dog, Stafford: Staffordshire Libraries, 1989.

Full title of the latter is found to be: Philip R. Leese, The Kidsgrove Boggart and the Black Dog: A Version of the Story and an Examination of the Written Source. A 32 page booklet. This is new to my North Staffordshire Folk-lore bibliography, and will be in the next edition.

Not published as full-text or identified as North Staffordshire in the Boggart Sourcebook is the reference…

* Wigfull, Chas. S. ‘Alton Addenda’, Derbyshire Advertiser, 6th May 1927, page 31.

I suspected this was Alton in the Moorlands. Cross-referencing this with the list of ‘Boggart Names’ in the book shows that this newspaper article had noted a named “Barberry Gutter Boggart”. This gave me a lead to follow. Folk-lore journal (1941) usefully stated that the Gutter was located “on the road from Alton to Farley”. In Folk-lore, the places referenced either side show that the Manifold Valley area is under discussion. Hence, this is Staffordshire’s Alton and not some other Alton.

The new book offers a useful ‘Boggart Census’ for Derbyshire, none of which are items shading over toward Staffordshire. The same is true of Cheshire. It then appears our Kidsgrove Boggart is very much an outlier.

But my above winkling out of the “Barberry Gutter Boggart” at Alton now gives North Staffordshire one more boggart.

Where, then, is or was the Barberry Gutter? Folk-lore tells us this was “on the road from Alton to Farley”, and interestingly one also finds there a headless horseman riding a white horse and clad in armour (again, according to Folk-lore). Such rural tales are admittedly common and often late confabulations, but it might be interesting to know if it can be found before the re-discovery of the very nearby head-chopping tale of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

A study of local molluscs for the journal of the North Staffordshire Field Club (1921) adds a little more data to the location of this Gutter. The diligent mollusc-hunter Mr Atkins noted a colony thriving under damp fir-bark at Alton on or near the…

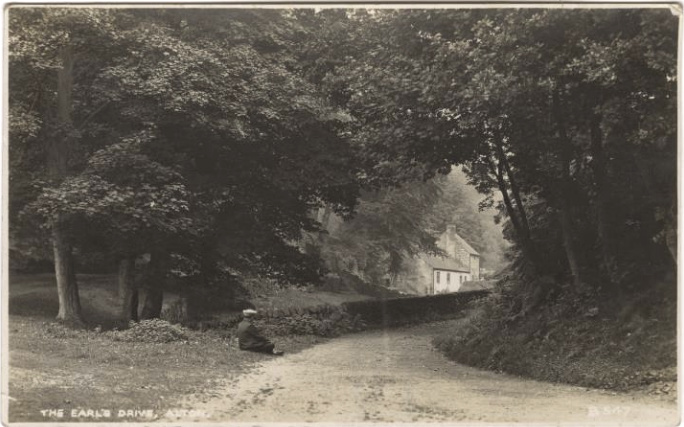

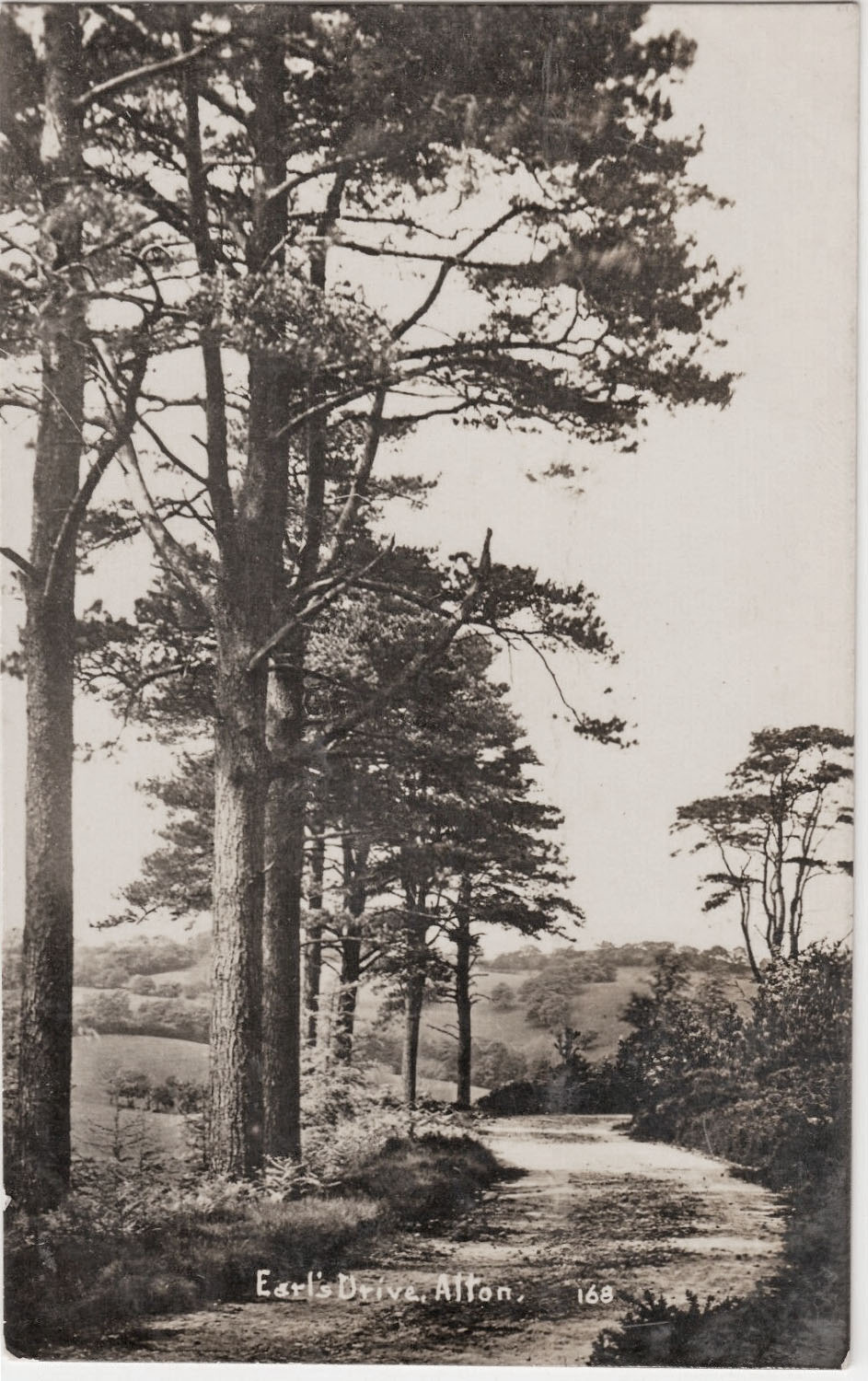

Earl’s Drive, Barberry Gutter

The boggart could then be somewhere along the well-known “Earl’s Drive”. The drive having been built in the 1800s by the Earls of Shrewsbury, a lovely ride going over damp ground by a series of bridges. So far as I know this could also be used by the public.

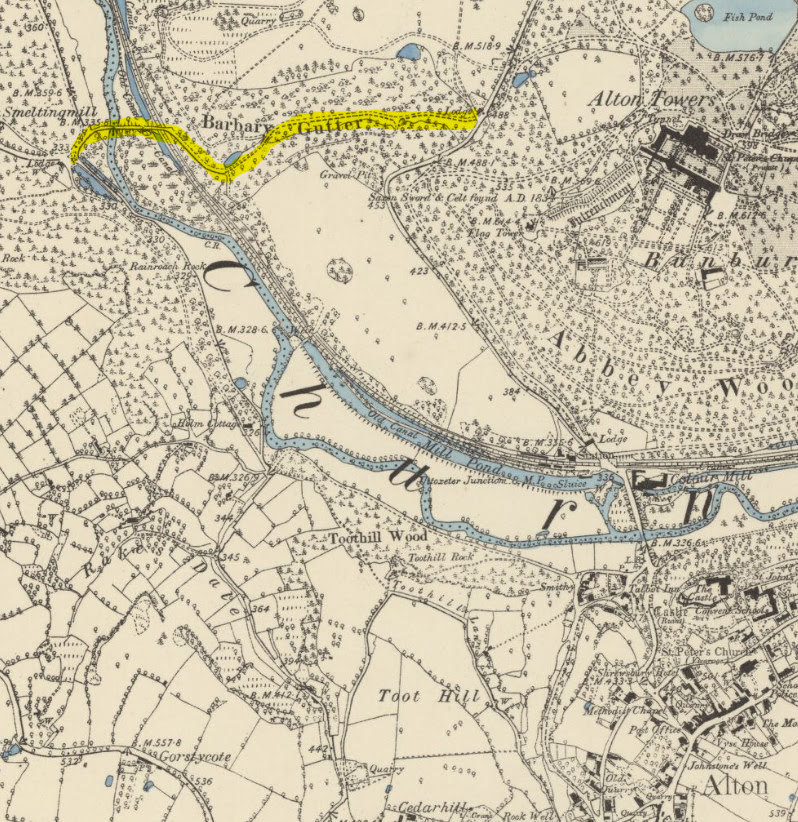

An old map then reveals the correct location of the Gutter, seen here spelled as “Barbary” and in relation to the Towers and the Castle…

It is thus also the location of the “Chained Oak”.

(This modern Earl’s Drive is not to be confused with the medieval Earlsway).

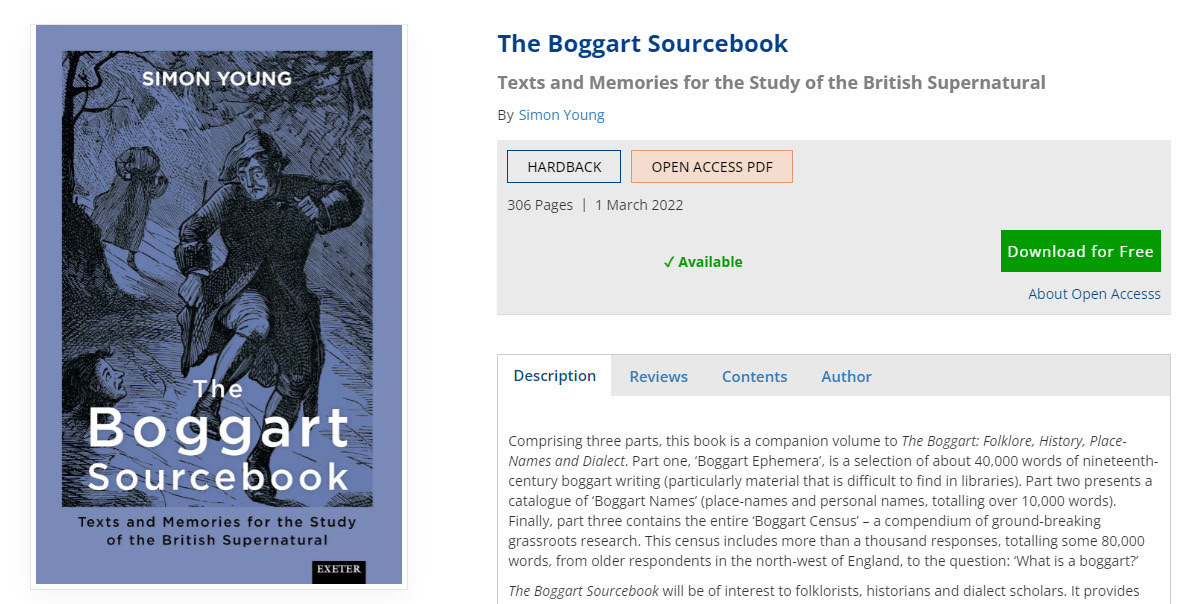

The Boggart Sourcebook

New in open access from the University of Exeter, The Boggart Sourcebook (2022)…

‘Boggart Ephemera’, is a selection of about 40,000 words of nineteenth-century boggart writing (particularly material that is difficult to find in libraries). Part two presents a catalogue of ‘Boggart Names’ (place-names and personal names, totalling over 10,000 words). Finally, part three contains the entire ‘Boggart Census’ – a compendium of ground-breaking grassroots research. This census includes more than a thousand responses, totalling some 80,000 words, from older respondents in the north-west of England, to the question: ‘What is a boggart?’

Not currently downloading, for me, on either my regular or my ‘clean of add-ons’ Web browser. But hopefully it will soon, and then I’ll know how much Staffordshire is in it.

Update: There is a way to get the PDF. unglue.it have it and they usefully offer a “Save to Dropbox” feature that works. The normal PDF download is still not working.

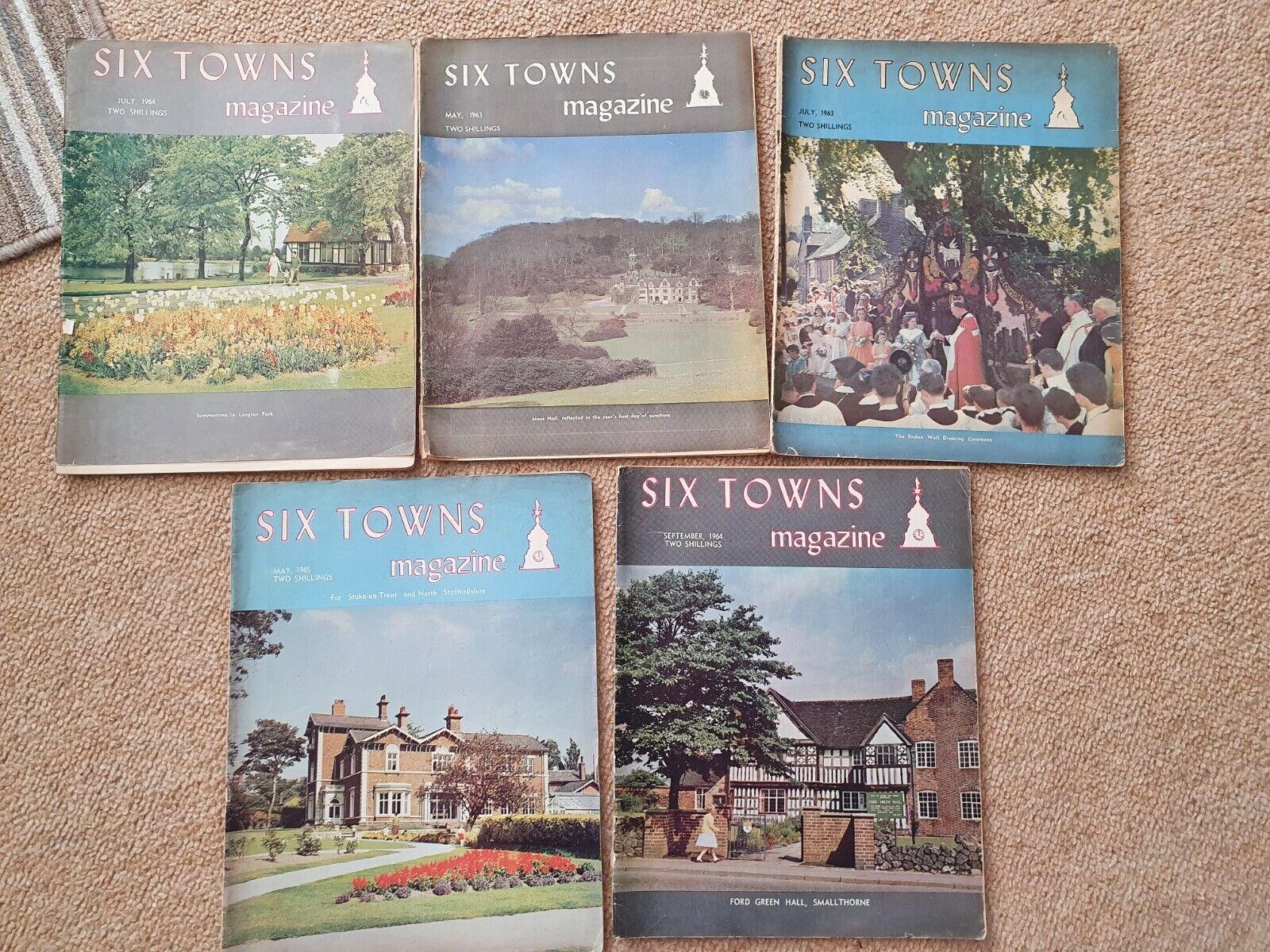

Six Towns Magazine

Another previously unknown local magazine discovered. As with others, this looks like it’s in need of digitization and being made public and searchable.

But I guess we really need a big well-funded digitization project for North Staffordshire, for many such publication runs. Because there’s so much that is languishing in the dusty archives and private collections.

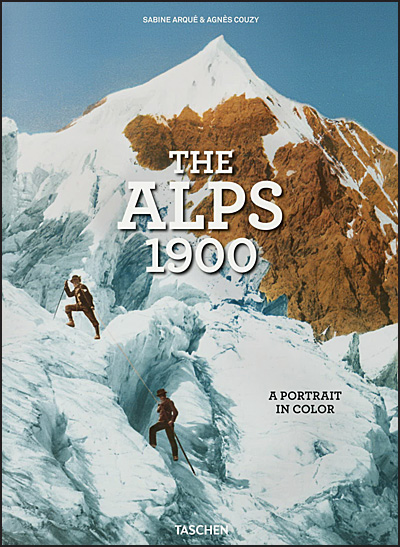

The Alps, 1900

Possibly of interest to scholars of the young Tolkien’s formative experiences. Due from sumptuous coffee-table publisher Taschen in September 2022, the oversized book THE ALPS 1900: A Portrait in Color. In their growing “1900” series, though seemingly not limited to that year. Note the alpine-high price of $200.

“The gigantic Alpine mountain range includes some of the most grandiose natural sites in the world, such as Mont Blanc, the Jungfrau, the Matterhorn, and their glaciers. Tourism began in the late 1800s and grew tremendously over the next centuries, especially with the rise of winter sports. This book offers a charming tour of a bygone era, when the first mountain trains and cog railways were carrying men in lederhosen and women in long dresses to the foot of the glacier, when local guides accompanied tourists riding on mules; a time when the first alpinists were considered mad, and skiers were a curiosity.

Through photochromes, photographs, and color postcards of the 19th and 20th centuries, through travel posters and tourist brochures, we cross passes such as the Mont-Cenis, Simplon, Brenner, and St. Gotthard; climb Mont Blanc, the Eiger, the Wetterhorn, and the Dolomites; marvel at crystal-clear lakes in Switzerland, Italy, Bavaria, and Slovenia; explore Tyrol, the Via Mala, and the Engadin; and spend the winter season at grand hotels in Gstaad, Grindelwald, Davos, St. Moritz, and Cortina. This is a journey dotted with literary quotes by travel writers that evokes these happy days of pristine snow and untouched slopes.”

‘Lord of The Roaches’, RIP

Sad to hear that King Doug, ‘The Lord of The Roaches’ has passed away. The Leek Post and Times has a tribute article with some biographical details. The Ludchurch blog also has a fine long article from 2012, which has attracted comments from those who knew him.

There’s also a 2015 book on his battles, and another from 1991 titled The Wars of The Roaches. I’m uncertain of the 2015 is a Lulu re-issue and update of the 1991 title, or a new book.

Chester City Walls

Chester Walls Complete Walking Tour. A complete two-mile circuit of the ancient walls, with a reasonably-balanced steadycam and a steady pace and hand. I didn’t get motion-sickness from it. The walk probably gets a lot more hectic where rammed with tourists, backpacks, dogs and the like. But here it’s people-free.

There’s no narration. It helps to know that the wide section by Chester Racecourse was once a key English port and the medieval civilian embarkation point for Ireland. But over time the river silted up and navigation became ever more difficult. Liverpool served larger ships and began to take over the trade. Later the railways took passengers to Holyhead for the crossing to Ireland. There is however still a river there (it now slides round the back of the Racecourse) and short boat-trips can be taken on it in the summer.

Recreation in 3D and more.

Sir Stanley & Sir Gawain

New online is a scholarly follow-up to a claim made for the identity of the elusive Gawain-poet. The bold claim made for Sir John Stanley was substantially revived in the journal Arthuriana in 2004. Now the author of that 2004 paper revisits his topic with his new “Did Sir John Stanley write Sir Gawain and the Green Knight?”, in SELIM : Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature, Vol. 27, No. 1 (2022).

I should stress this is not a claim I agree with. But reading the new essay closely, several times, was still enjoyable. The author here…

“offers a revised survey of publications before and after 2004, examining whether they strengthen the case for Stanley as the Gawain Poet, weaken it, or demolish it completely.”

He largely draws on literary academics who have looked for internal evidence of authorship in the texts. He either ignores or very gingerly skirts the deeper linguistic research, and he almost overlooks R.W.V. Elliott who was the key boots-on-the-ground researcher. But the new survey is still useful because so much work under discussion remains locked in paid academic databases, in out-of-print and near-unobtainable books, or in deeply obscure journals.

This new survey does not bring the reader up-to-date, however. There are many recent items missing that one would expect to find. Such as the recent major ERDF study of the supposed Norse influence on Gawain. It looks to me like this is an older paper that’s been slightly tweaked, so as to get into a current journal. Even then, also missing is key older work such as the essays in Derek Brewer’s A Companion to the Gawain-poet.

But that said, it’s still useful and is even entertaining — especially when it skewers a silly Marxist or two.

The reader will however need to be aware that there are a few unfortunate errors. For instance it is stated that…

1)

“Sir Israel Gollancz (1863-1930) made unconvincing proposals on the Gawain poem as written for an audience in North Wales, and a better one for the Green Chapel as in the rugged country of north-west Staffordshire (Gollancz 1940: xviii-xx). This area of the Peak District was in the Forest of Macclesfield. We shall use this as a clue to authorship [for Sir Stanley].”

Gollancz was dead by 1940, and in the book the introduction’s suggestion came from his student Mabel Day. She proposed Wetton Mill in North Staffordshire as a likely location for the Green Chapel, following the lead on the area given by Bertram Colgrave (1938) who had suggested the nearby Bridestones burial-chamber. But Wetton Mill was outside the medieval Forest. The ‘old forest law’ Forest of Macclesfield ended at the boundary formed by the River Dane, as the standard A History of Macclesfield states…

“The Forest of Macclesfield was bounded on the east by the rivers Goyt and Dane, from Otterspool bridge, near Romiley, in the north, to Bosley in the south. The western boundary was approximately the present London Road from the Rising Sun Inn to Prestbury, from thence along the Macclesfield township boundary to Gawsworth, where it avoided the precincts of the church and continued south to the Dane.”

The Forest did not go across the Dane and then miles further SE to also encompass Wetton Mill and the Manifold Valley area. Even a rampaging hunt in full cry and pursuit of a fast stag, and heedless of the strictly patrolled hunting rights of the time, would not have got that far. Nor, it might be further noted, did it encompass the cleft of Ludchurch.

Incidentally, later in the essay we learn that Sir Stanley did anyway not have the Forestership of Macclesfield until 1403, rather late for Gawain. Nor was he a justice until 1395, and seemingly only for a year. He is, on these and many other counts, simply too late in time.

2)

“Elliott’s belief that the poet was perhaps a monk on a monastic estate must be rejected. There is nothing monastic in the four poems attributed to him [the poet]”

This claim is unfortunately un-referenced, and Elliot’s extensive work is even more unfortunately omitted entirely from the bibliography! Did Elliot ever suggest a “monk” as the Gawain-poet? If so, where? There is some mention of monks in the initial 1958 Times newspaper article. But I recall Elliott saying very clearly in print that the poet was not monastic, and indeed it was from Elliot that I first took this important warning point when I started my research. I can only imagine that some memory of ‘Eliot suggesting the Grange at Swythamley’ has for some writers come to = ‘therefore, the Gawain-poet was a monk’. But that is not the inference to take, and would overlook important factors such as…

i) the practice of lodging and educating noble younger sons in humbler-yet-educated circumstances, in other nearby households. Also done so as to make the young lords less arrogantly cock-a-hoop, among other reasons.

ii) Dieulacres Abbey monks and estate men of the Grange effectively serviced and partly administered the hunting in the Peak. We know this because they complained bitterly to the King in the 1350s when too many nobles and their dogs and servants descended on them to enjoy the Peak hunting. Even though the religious did not hunt themselves, in circumstances such as the Grange on the Dane they would often have been cheek-by-jowl with those who did. “Canon law barred clerics from blood sports”, as the new essay states. Though one Abbot who went hawking and fishing can be found in England in the 1360s, and possibly there were others.

Also, it is likely that the managed hunting grounds are a good ‘warm-up’ ride from the castle in Gawain. They do not have to a stone’s throw from the castle drawbridge, as some academics (not the one under discussion here) seem to assume. One would not want a hunt and dogs rampaging around on one’s own doorstep, and a valuable horse also needs to be ‘limbered up’ with a good ride before a strenuous mid-winter hunt.

3)

The new essay’s plague numbers and dates seem a little ‘off’, and are ‘off’ in favour of the later Sir Stanley…

“In fourteenth century England there were five great outbreaks of plague, the last two being in the late 1370s and between 1390 and 1393.” … “there was an epidemic from 1390 to 1393”.

The three main waves were in 1349 (the first), then in 1361 (especially severe in North Staffordshire, Croxden Abbey recorded “all the children died”) and 1379 (20% mortality, hardly reaching North Staffordshire). As for the others the book Biology of Plagues: Evidence from Historical Populations (Cambridge University Press, 2005) states… “In 1379-80 there was a plague [the fourth] apparently confined largely to the counties of northern England [meaning the parts adjacent to Scotland].” “The fifth plague hit in 1389-1391” [and appears to have been especially virulent in the damp eastern fenlands of England].

4)

There are also some assumptions that, while not mistakes, might have been usefully questioned. Such as…

“Nor would he [the Gawain-poet] have lived among those hills and moors, though he certainly hunted on them … His residence will have been a great hall in the lowlands of the north-west”.

Why have academics — including this author — always totally overlooked Alton Castle? It’s as though the place has an academic ‘invisibility cloak’ around it. Even Elliot, who had boots-on-the-ground in North Staffordshire for years, seems to have gone no further than ‘his bit’ of the ancient Earlsway. He never once asked where the Earlsway at Waterhouses might have led to. It was pointing to a massive medieval castle not far off, that’s where — one fitting the bill perfectly in both its period, fabric and owners, and perched right in middle of the ‘Hautdesert’ and just 14 miles from the dialect “ground-zero”.

There was a reference new to me. T. Turville-Petre, “The Green Chapel”. IN: O. J. Padel & D. N. Parsons (Eds.), A Commodity of Good Names, Shaun Tyas, 2008. Sadly the book is one of those festschrift titles which are barely publicised and which hide away good scholarly work in soon-unobtainable books. Forced open-access for all taxpayer-salaried writers of arts and humanities texts can’t come soon enough for me.

There is one review of this festschrift which helps illuminate the article…

“Torlac Turville-Petre considers “The Green Chapel”, convincingly discussing the ways in which the Gawain-poet, in his description of the Green Chapel, uses topographic imagery in line with the Peak District, where the Poet came from, thus making real for his audience the supernatural world the characters inhabit.”

Sounds like it might follow on from Elliot’s dogged fieldwork? Curiously, I find that Turville-Petre’s very un-illuminating short entry in the Oxford Handbook of Medieval English Literature decides (on no referenced evidence) to place the Green Knight’s castle in the Wirral of all places. Put both his texts together and one must wonder quite how Gawain gets so quickly all the way from a castle supposedly in the Wirral to the upland hunting / Green Chapel in the Peak / Staffordshire Moorlands. In the tale the two places are only supposed to be a few miles apart, not the 50 miles by winding horse-tracks and salt-ways that separated the Wirral from the Manifold Valley.

Anyway, in a vain search for further reviews of A Commodity of Good Names I also stumbled on a gem. An open 300-page PhD thesis from 2019 on Barrows In The Cultural Imagination of Later Medieval England. Enjoy.

More Potteries Post

The Potteries Post – From the city of Stoke-on-Trent and beyond, news you can use. Not much local creative / eco news at present, as we’re moving into sleepy August, but there’s still a smattering to be had. The Post will be in “slow mode” for August, and back in early September.