I’ve only very recently heard of another major novel set in the Potteries, George Moore’s A Mummer’s Wife (1884, revised 1886). I didn’t have this on my otherwise comprehensive survey of “Novels and fictions set in Stoke-on-Trent”. Possibly it has escaped the notice of local people, including myself, because post-1985 critics making a survey of the history of the English novel have blandly parroted that it has a “Midlands” setting — as if the “Midlands” were a single and uniform place.

Yet the book is substantially set at the heart of the Potteries, when the story opens. Better, the novel was researched in an ethnographic manner by the author. Philip Edwards, in Threshold of a Nation (1983) remarked of Moore that…

“He had travelled for some weeks with a touring company [of actors] in the Potteries in order to give authenticity to A Mummer’s Wife.”

It appears that this realist novel (it has a strong claim to be the first such set in England) provided tight-laced late Victorian England with a startling realist depiction of female romantic sentiments and desire — both intellectual and physical. The poet W. B. Yeats “forbade his sister to read it”, and it was banned from two of the popular travelling libraries of the time. There was much comment on it in the press, some favourable. Moore’s first novel, A Modern Lover (1883) had apparently been “banned in England” a year earlier, and it appears that his second novel benefited in its sales from his notoriety.

There’s now a critical edition of the book in paperback and Kindle (above), and it’s also free on Archive.org in the revised 1917 edition. There appears to be no audiobook.

Initially there appears to be very little topographical description in the book, and we could indeed be in a vaguely generic “Midlands”. For the first 60 pages the focus seems to be resolutely on the characters and their interactions, though there is an interesting broad account of the early education of the heroine’s sentiments and tastes. The author appears at first to have been writing purely for his times, and so assuming that all his readers would be generally familiar with the look of working life and streets.

But after page 60 one can see that this is his very clever literary feint. His plain opening for the novel conveyed the narrowness and insular nature of the heroine’s life. But from page 60 she meets her future Bohemian actor-lover, and the landscape of the Potteries suddenly bursts into vibrant topographic description…

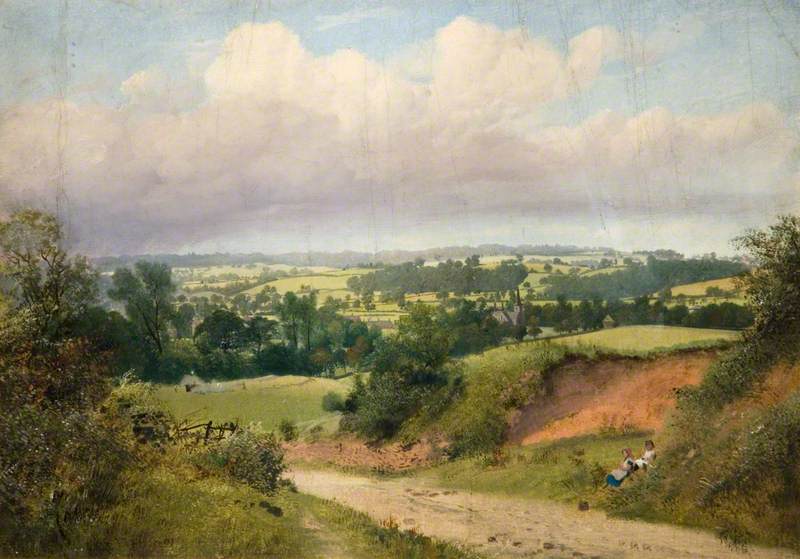

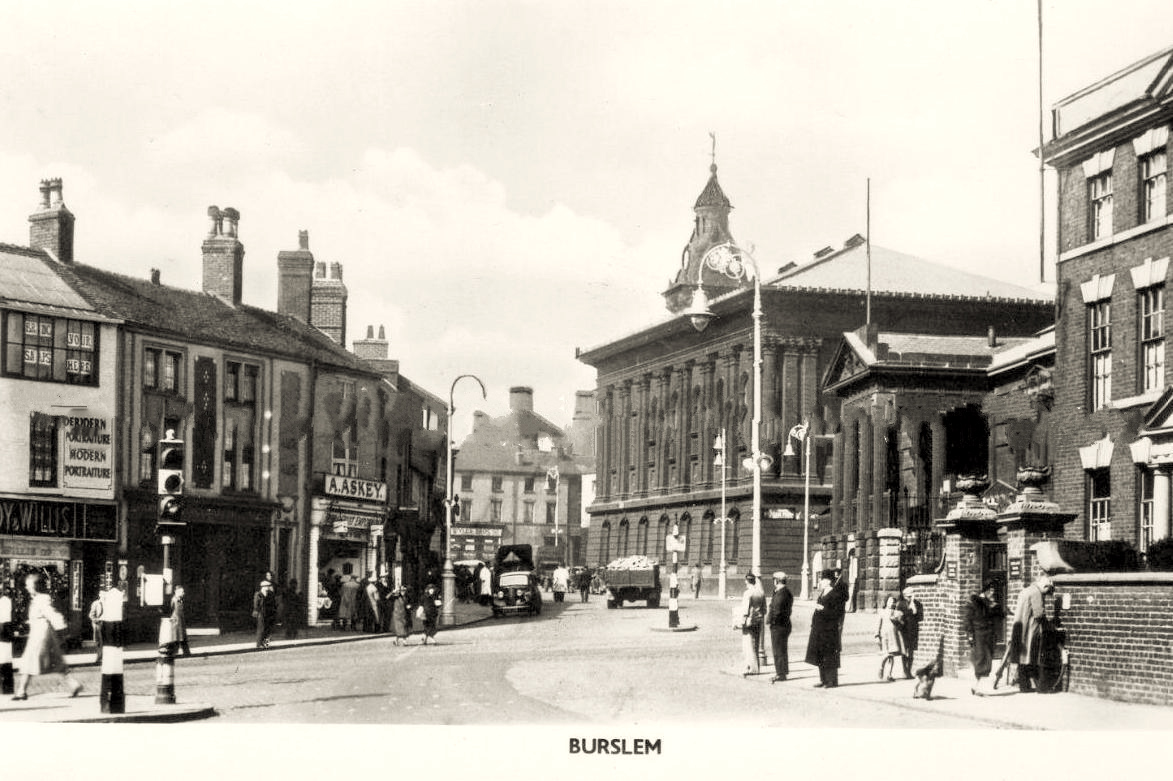

“… at the top of Market Street she stood at gaze, surprised by the view, though she had never seen any other. A long black valley lay between her and the dim hills far away, miles and miles in length, with tanks of water glittering like blades of steel, and gigantic smoke clouds rolling over the stems of a thousand factory chimneys. She had not come up this hillside at the top of Market Street for a long while; for many years she had not stood there and gazed at the view, not since she was a little girl, and the memories that she cherished in her workroom between Hanley and the Wever Hills were quite different from the scene she was now looking upon; she saw the valley with different eyes; she saw it now with a woman’s eyes, before she had seen it with a child’s eyes. She remembered the ruined collieries and the black cinder-heaps protruding through the hillside on which she was now standing. In childhood these ruins were convenient places to play hide-and-seek in. But now they seemed to convey a meaning to her mind, a meaning that was not very clear, that perplexed her, that she tried to put aside and yet could not. At her left, some fifty feet below, running in the shape of a fan, round a belt of green, were the roofs of Northwood black brick unrelieved except by the yellow chimney-pots, specks of colour upon a line of soft, cotton-like clouds melting into grey, the grey passing into blue, and the blue spaces widening.

‘It will be a hot day,’ she said to herself, and fell to thinking that a hot day was hotter on this hillside than elsewhere. At every moment the light grew more and more intense, till a distant church spire faded almost out of sight, and she was glad she had come up here to admire the view from the top of Market Street. Southwark, on the right, as black as Northwood, toppled into the valley in irregular lines, the jaded houses seeming in Kate’s fancy like cart-loads of gigantic pill-boxes cast in a hurry from the counter along the floor. It amused her to stand gazing, contrasting the reality with her memories. It seemed to her that Southwark had never before been so plain to the eye. She could follow the lines of the pavement and almost distinguish the men from the women passing. A hansom [cab] appeared and disappeared; the white horse seen now against the green blinds of a semi-detached villa showed a moment after against the yellow rotundities of a group of pottery ovens.

The sun was now rapidly approaching the meridian, and in the vibrating light the wheels of the most distant collieries could almost be counted, and the stems of the far-off factory chimneys appeared like tiny fingers.

Kate saw with the eyes and heard with the ears of her youth, and the past became as clear as the landscape before her. She remembered the days when she came to read on this hillside. The titles of the books rose up in her mind, and she could recall the sorrows she felt for the heroes and heroines. It seemed to her strange that that time was so long past and she wondered why she had forgotten it. Now it all seemed so near to her that she felt like one only just awakened from a dream. And these memories made her happy. She took pleasure in recalling every little event an excursion she made when she was quite a little girl to the ruined colliery, and later on, a conversation with a chance acquaintance, a young man who had stopped to speak to her.

At the bottom of the valley, right before her eyes, the white gables of Bucknell Rectory, hidden amid masses of trees, glittered now and then in an entangled beam that flickered between chimneys, across brick-banked squares of water darkened by brick walls.

Behind Bucknell were more desolate plains full of pits, brick, and smoke; and beyond Bucknell an endless tide of hills rolled upwards and onwards. […] every wheel was turning, every oven baking; and through a drifting veil of smoke the sloping sides of the hills with all their fields could be seen sleeping under great shadows, or basking in the light. A deluge of rays fell upon them, defining every angle of Watley Rocks and floating over the grasslands of Standon, all shape becoming lost in a huge embrasure filled with the almost imperceptible outlines of the Wever Hills.

And these vast slopes which formed the background of every street were the theatre of all Kate’s travels before life’s struggles began. It amused her to remember that when she played about the black cinders of the hillsides she used to stop to watch the sunlight flash along the far-away green spaces, and in her thoughts connected them with the marvels she read of in her books of fairy-tales. Beyond these wonderful hills were the palaces of the kings and queens who would wave their wands and vanish! A few years later it was among or beyond those slopes that the lovers with whom she sympathized in the pages of her novels lived. But it was a long time since she had read a story, and she asked herself how this was. Dreams had gone out of her life. […] The thought caught her like a pain in the throat, and with a sudden instinct she turned to hurry home. As she did so her eyes fell on Mr. Lennox [a genial visiting actor, one of a travelling troupe] walking towards her. At such an unexpected realization of her thoughts she uttered a little cry of surprise; but, smiling affably, and in no way disconcerted, he raised his big hat from his head. On account of the softness of the felt this could only be accomplished by passing the arm over the head and seizing the crown as a conjurer would a pocket-handkerchief. The movement was large and unctuous, and it impressed Kate considerably.

[She meets the actor, the “mummer” of the book’s title. They talk…]

Overhead the sky was a blue dome, and so still was the air that the smoke-clouds trailed like the wings of gigantic birds slowly balancing themselves. And waves of white light rolled up the valleys as if jealous of the red, flashing furnaces. […] All was red brick blazing under a blue sky without a cloud in it; the red brick that turns to purple; and all the roofs were scarlet red brick and scarlet tiles, and not a tree anywhere. […] He had never seen a town before composed entirely of brick and iron. A town of work; a town in which the shrill scream of the steam tram as it rolled solemnly up the incline seemed to be man’s cry of triumph over vanquished nature. […] Out of a sky burnt almost to white the glare descended into the narrow brick-yards. The packing straw seemed ready to catch fire…

It was probably vivid early passages such as these that Arnold Bennett was recalling in 1920, when he wrote to George Moore…

“I wish to tell you that it was the first chapters of [your] A Mummer’s Wife which opened my eyes to the romantic nature of the district that I had blindly inhabited for twenty years. You are indeed the father of all my Five Town Books.”

This debt must have become public knowledge, because St. John Irving commented on the matter two years later in 1922…

“… it is ludicrous to imagine that but for the happy accident of reading “A Mummer’s Wife” he [Bennett] would never have [written his Five Town Books] but it is not improbable that Mr. Moore’s story brought him to his proper milieu earlier than he might otherwise have reached it. The reader can profitably entertain himself by comparing “the Five Towns,” the places and the people, of “A Mummers Wife” with “the Five Towns,” places and people of “The Old Wives’ Tale” and “Clayhanger.” The difference between Mr. Moore’s account and Mr. Bennett’s is the difference between careful and acute observation by an intelligent stranger, alien in birth and tradition and training, and the knowledge, inherited from his forefathers and acquired in childhood and youth, of a native. Mr. Moore had to “mug up” his subject, as schoolboys say, but Mr. Bennett was born with most of it. The description of Hanley in the first chapter of “The Old Wives’ Tale” (where it is named Hanbridge by Mr. Bennett) contrasts remarkably with the description of the same town in “A Mummers Wife,” as does the description of a pottery seen through Mr. Bennett’s eyes …”

Several histories of the English novel, accessible via Google Books, also mention that that the debt was a wider one. In its ground-breaking and boldly amoral treatment of a variety of gritty domestic subjects, and also by placing a reading and imaginative working-class woman at the heart of a novel, A Mummer’s Wife had opened up a space of free expression for all English authors that had simply not existed before.