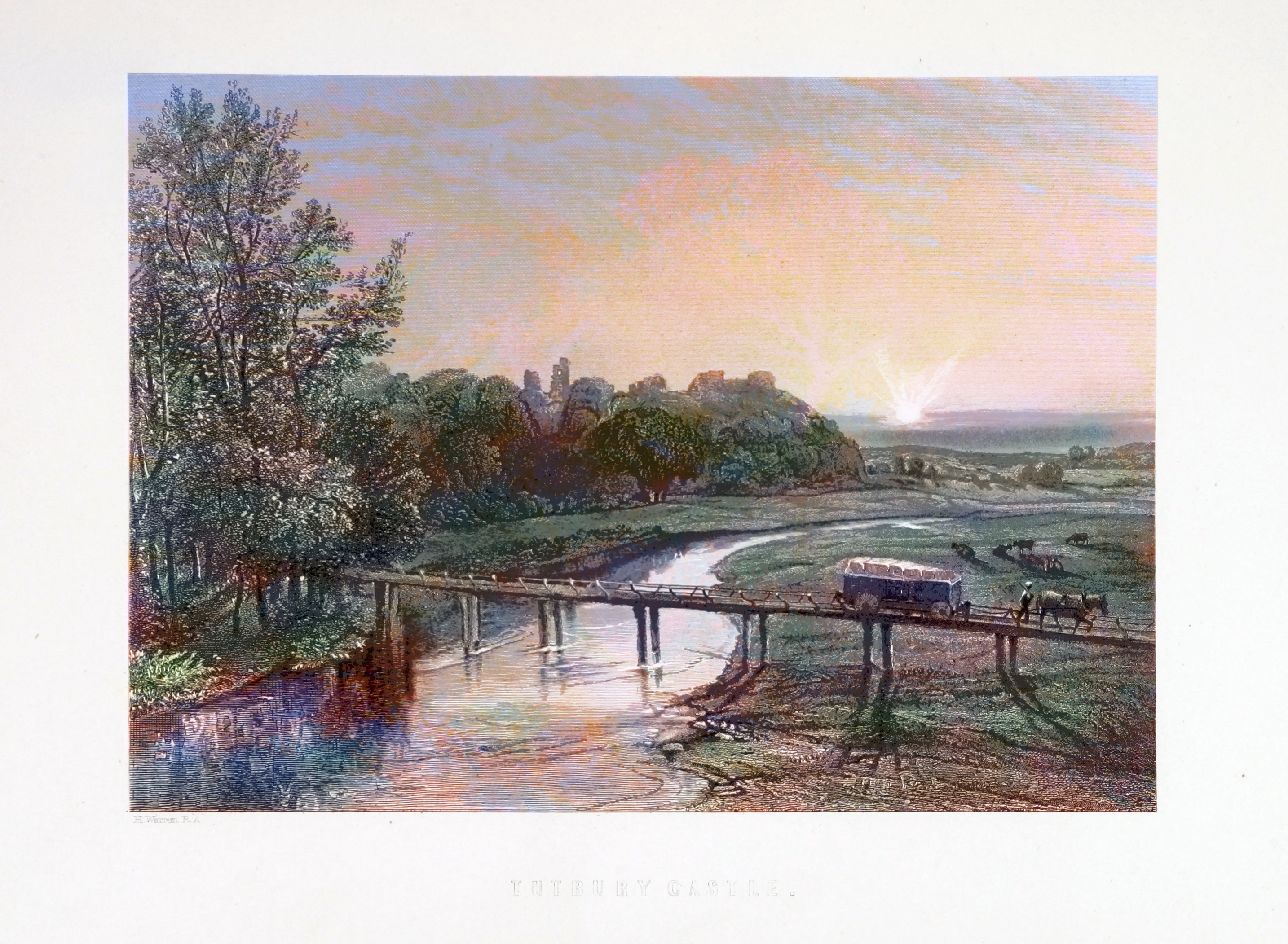

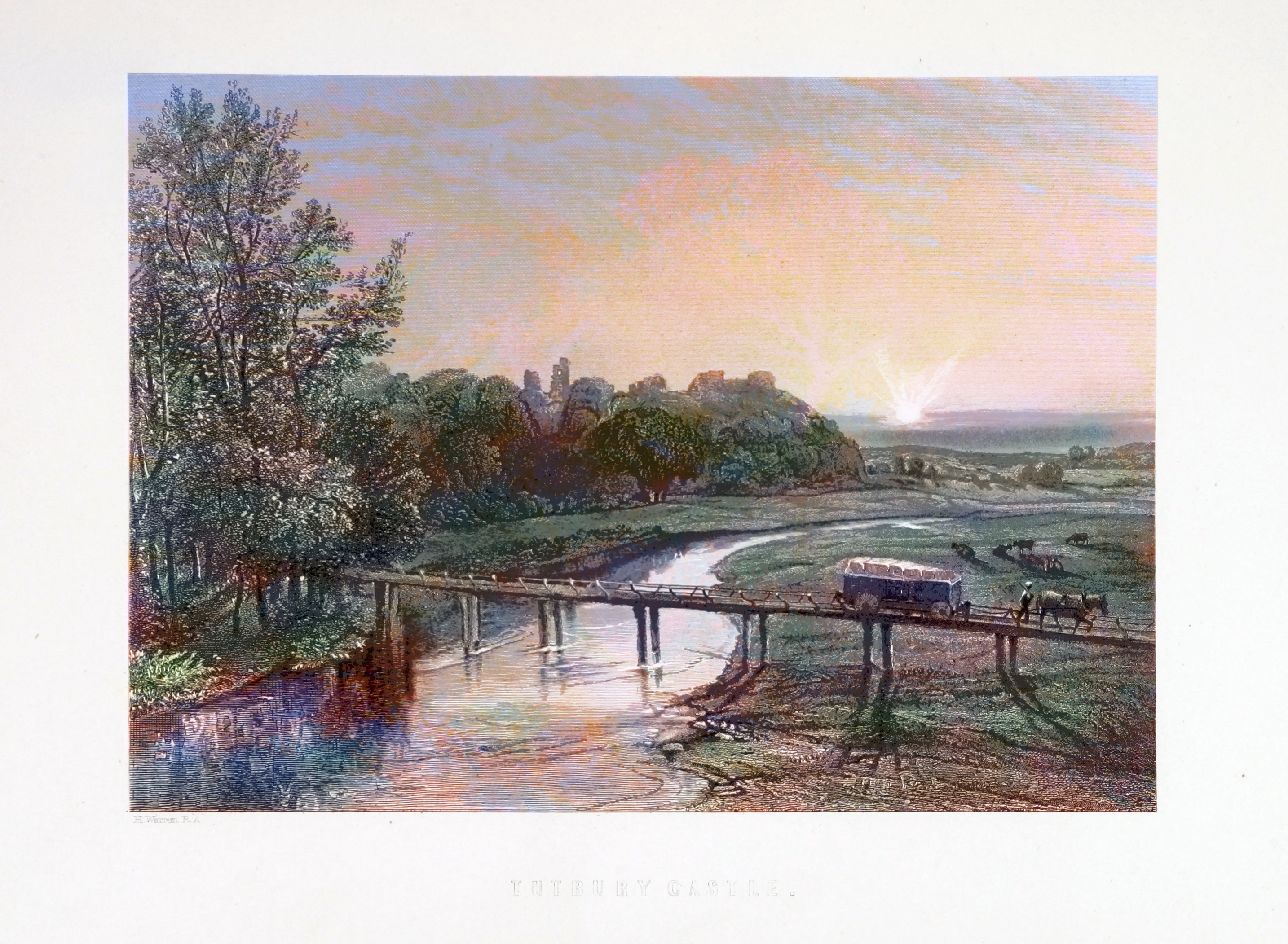

There was once a large annual minstrel court at Tutbury in Staffordshire, between Uttoxeter and Burton-on-Trent.

James Lawson Stewart (1829-1911). “The main gateway, Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire”.

James Lawson Stewart (1829-1911). “The main gateway, Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire”.

The Topographical History of Staffordshire has it that Tutbury: “came into the possession of John of Gaunt, who re-built it of hewn freestone, upon the ancient site” and used it to house his wife Constance from 1372. Under Constance (d. 1394), the minstrel court was either revived or established or enlarged. The translated wording of the Court charter (c. August 1381) is given by Oswald Mosley in his History of the Castle, Priory and Town of Tutbury (1832) and appears to suggest that Constance took over the patronage of a much older annual gathering…

“the King of the Minstrels, [elected by his peers] in our Honor of Tutbury, [is obliged] to apprehend and arrest all the minstrels in our said Honor and Franchises, that refuse to do the service and attendance which appertains to them to do from ancient times at Tutbury aforesaid, yearly on the days of the Assumption of our Lady, giving and granting to the said King of the Minstrels, for the time being, full power and commandment to make them reasonably to justify, and to constrain them to perform, their services and attendance, in manner as belongeth to them, and has been here used, and of ancient times accustomed.”

The statement “from ancient times” may be formulaic, but it may also suggest that the gathering still existed. Or had once existed as evidenced by some ancient documentation, at Tutbury.

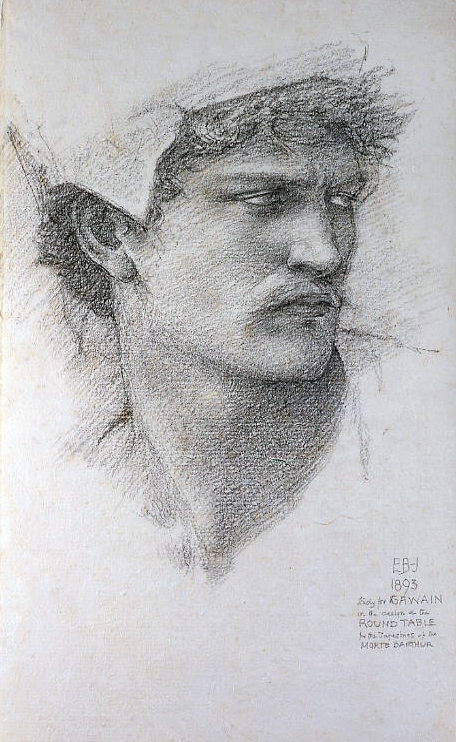

Court bard engraved on ivory inlay, circa 1550s, possibly Nuremberg.

Court bard engraved on ivory inlay, circa 1550s, possibly Nuremberg.

There may have been several reasons for the establishment of such a court under informal patronage:

i) Constance was from Castile in Spain, and may have been used to a higher level of courtly culture. We know she had singers from her own country at Tutbury, and it seems she also aspired to raise the ‘tone’ of the surrounding countryside too;

ii) the absolute need to relieve the local gloom and despair after the third Black Death plague of 1379-80, and perhaps a perceived need (within a ‘god was punishing us with the plague’ mindset) to make minstrelsy more Christian in tone and less bawdy than before;

iii) perhaps for a political reason, namely to prevent local minstrels from needing to travel into Wales to the Welsh bardic gatherings. From c. 1350 the Welsh had been more revolting and sullen than usual, and their resident overlords suspected a Welsh spy under every bed and that the Welsh might rise and march an army of rebels into England at any moment. The Welsh threat, and the threat of their linking with an army coming down the drove roads from Scotland, was probably why Stafford Castle was rebuilt from 1347. The imminence of the threat may have abated by the 1370s, but was still there — “before 1400 conditions in Wales were ripe for rebellion” (The Oxford Companion to British History);

iv) the three waves of the Black Death plague must have caused a sharp decline in available audiences, it having especially affected the young. Smaller paying audiences likely meant an increase in disputes and rivalries among minstrels. Plague may also have sent survivors out to earn their living as minstrels, leading to increased fines as ‘vagabonds’. In an ordered society these would require arbitration to prevent disputes and fines from getting out of hand.

v) what academics now call “the alliterative revival” in the Midlands, and the renewed interest in the making of local dialect poetry from c. 1350 onwards.

I’m no expert but lordly castle use appears to me to have been seasonal, with full occupation especially likely during the Christmas season. Judging by biographies, Tutbury Castle appears to have become the full-time home to Gaunt’s wife Constance, Duchess of Lancaster, winter and summer alike. She eventually disassociated herself from Gaunt and from the Lancastrians, but even after she had outlived her political usefulness to Gaunt she was allowed to live on in comfort at Tutbury. By all accounts she was someone who not only patronised musicians but also made a study of the science of music.

Mosley’s History of the Castle, Priory and Town of Tutbury (1832) is unreliable, but not so when quoting older documents. He usefully gives an extract from Plot’s The Natural History of Stafford-shire (1686) without the long-s typography. Plot was an eye-witness to the annual minstrel court at Tutbury…

“All the minstrels within the honor, came early on that day [noted elsewhere: the court was on ‘the morrow after the Assumption’, meaning the 16th August] to the house of the bailiff of the manor of Tutbury, and from thence to the parish church in procession ; the king of the minstrels for the year past, walking between the steward and bailiff of the manor, attended by the four stewards of the king of the minstrels, each with a white wand in their hands, and the rest of the company following in ranks of two and two together, with the music playing before them.

After [the church] service was ended, they proceeded in the same order from the church to the castle hall, where the said steward and bailiff took their seats, placing the king of the minstrels between them, whose duty it is to cause every minstrel dwelling within the honour, who makes default, to be presented and amerced [i.e. a fine would be ordered if the minstrel was found to be absent]. The court of the minstrels is then opened in the usual way, and proclamation made, that every minstrel dwelling within the honour of Tutbury, in any of the counties of Stafford, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, or Warwick, should draw near, and give his attendance; and that if any man would be assigned of suit or plea [i.e. have a grievance], he should come in and be heard.

Then all the musicians being called over by a court roll, two juries are impanelled, one for Staffordshire, and one for the other counties, whose names being delivered in to the steward, and called over, and appearing to be full juries, the foremen of each is sworn, and then the rest of them in the manner usual in other courts. The steward then proceeds to charge them, first commending to their consideration the antiquity and excellence of all music, both on wind and stringed instruments; and the effect it has upon the passions, proving the same by various examples; how the use of it has always been allowed in praising and glorifying God; and skill in it esteemed so highly, that it has always been ranked amongst the liberal arts, and admired in all civilized states ; exhorting them, upon this account, to be very careful to make choice of such men to be officers amongst them as fear God, are of good life and conversation, and have knowledge and skill in the practice of their art.

When the charge is ended, the jurors proceed to the election of the officers for the next year, the king being chosen out of the four stewards, two of them out of Staffordshire, and two out of Derbyshire, three being chosen by the jurors, and the fourth by him who keeps the court, and the deputy steward, or clerk.

The jurors then depart out of the court; and the steward with his assistants, and the king of the minstrels, in the meantime partake of a banquet, during which the other musicians play upon their several instruments; but as soon as the jurors return, they present, in the first place, the new king whom they have chosen, upon which the old king, rising from his seat, delivers to him his wand of office, and then drinks a cup of wine to his health and prosperity; in like manner the old stewards salute the new, and resign their offices to their successors.

The election being thus concluded, the court rises, and all repair to another large room within the castle, where a plentiful dinner is prepared for them; after which the minstrels went anciently to the priory gate, but after the dissolution [of the monasteries], to a barn near the town, in expectation of the bull being turned loose for them. […]

If the bull escapes, he remains the property of the person who gave it; but if any of the minstrels can take and lay hold of him [without use of any weapons or hooks], so as to cut off a small portion of hair, and bring the same to the market-cross, in proof of their having taken him, the bull is [theirs to be cooked and eaten, or given away].

Mosley’s History of the Castle, Priory and Town of Tutbury, also notes that…

“A separate chair was placed for him [the annual elected King of the Minstrels?] at the upper end of the hall [at Tutbury?], which he never failed to occupy upon all public occasions; from hence he excited the feelings of his guests by the rehearsal of some mysterious legend, the warlike exploits of their ancestors, or some pathetic [‘tragic, sad’] ballad of general interest.”

The threat of arrest by the King of the Minstrels, together with the opportunity to air one’s pent-up grievance in public, surely brought every reputable minstrel to the annual court.

Mosley’s History of the Castle, Priory and Town of Tutbury (1832) also gives another document, from a little before Dr. Plot’s time. By the time of King Charles the First it was obviously felt that there was need for better governance of the Court and an order (c. 1630) was issued “for the better ordering and governing” of the Court. A system of seven year apprenticeship was also then in force locally…

“that no person shall use or exercise the art and science of music within the said counties as a common musician or minstrel for benefit and gains, except he have served and been brought up in the same art and science by the space of seven years, and be allowed and admitted so to do at the said court by the jury thereof and by the consent of the steward of the said court for the time being, on pain of forfeiting for every month that he shall so offend, three shillings and fourpence. And that no such musician or minstrel, shall take into his service, to teach and instruct any one in the said art and science, for any shorter time than for the space of seven years, under the pain of forfeiting for every such offence forty shillings. And that all the musicians and minstrels above mentioned shall appear yearly at the court called The Minstrels Court, on pain of forfeiting for every default according to old custom three shillings and fourpence.”

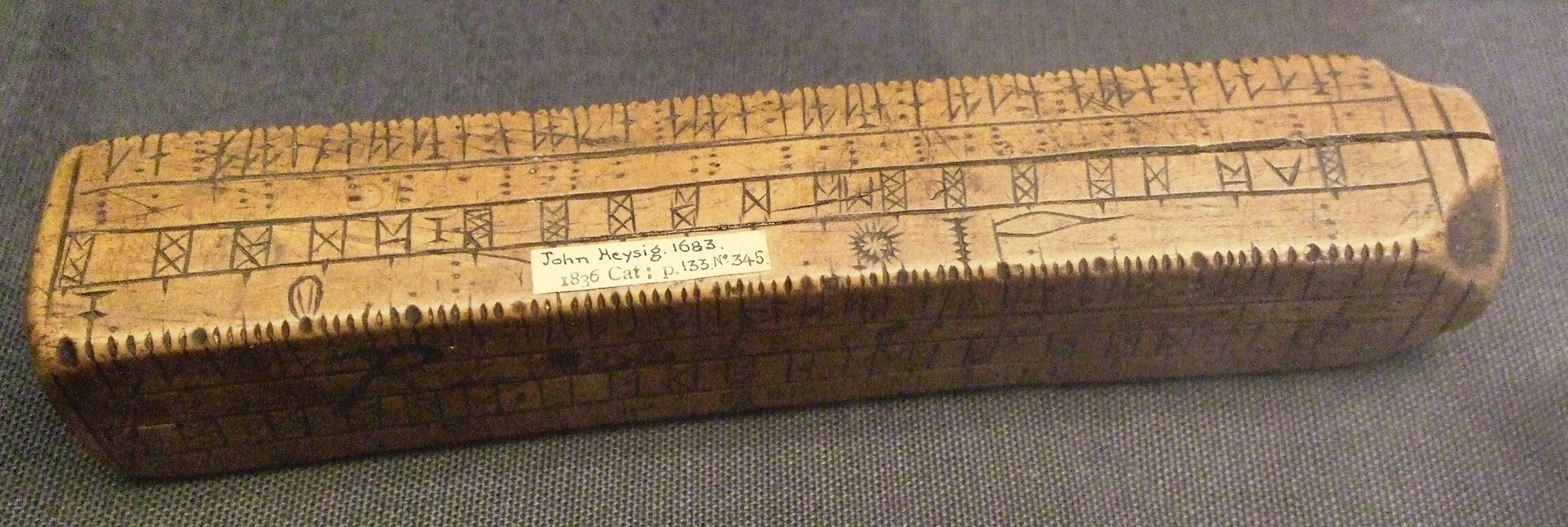

Minstrel on a fabric book-cover, London, 1636.

Minstrel on a fabric book-cover, London, 1636.

The Court appears to have been formally abolished by the Duke of Devonshire in 1778, who deemed it too unruly. At least, he issued an order to stop it at Tutbury. But the bull-running seems to have continued in the district into the early 1800s, as was vividly recalled at Uttoxeter in Mary Howitt’s My own Story, or the Autobiography of a Child (1845). If there were no minstrels, there would likely have been no bull-running (since a bull was a costly animal). Thus it seems likely that the summer minstrel gathering and bull-running had simply been transferred (c. 1779) by the locals from Tutbury to Uttoxeter, and the Duke’s patronage was dispensed with and the cost of ‘a feast and bull’ found from some other source. One would then expect such an event to attract at least some singers and entertainers, but if they were still present in large numbers as late as the early 1800s at Uttoxeter must be debatable. Yet the crowds for the bull-running at Uttoxeter might have still attracted lesser figures, like “Singing Sam of Derbyshire”…

a Derbyshire ballad-singer of the last century, “Singing Sam of Derbyshire” as he was called, which I copy from the curious plate etched by W. Williams in 1760, which appeared in the “Topographer” thirty years after that time. The man was a singular character—a wandering minstrel who got his living by singing ballads in the Peak villages, and accompanying himself on his rude single-stringed instrument. … His instrument was as quaint and curious as himself. It consisted of a straight staff nearly as tall as himself, with a single string tied fast around it at each end. This he tightened with a fully inflated cow’s bladder, which assisted very materially the tone of the rude instrument. His bow was a rough stick of hazel or briar, with a single string; and with this, with the lower end of his staff resting on the ground, and the upper grasped by his right hand, which he passed up and down to tighten or slacken the string as he played, he scraped away, and produced sounds which, though not so musical as those of Paganini and his single string, would no doubt harmonize with Sam’s rude ballad, and ruder voice. [he was one of the older illiterate type who] who sang his ballads from memory, and probably composed many of them as he went on, so as to suit the localities and the tastes and habits of his hearers, [and he was in stark competition with the newer type who sang] from a printed broad-sheet, of which he carries an armful with him to dispose of to such as cared to purchase them. [The new type of singer wa]s literally a “running stationer,” “such as use to sing ballads and cry malignant pamphlets in the streets,” and indulged their hearers in town and country with “fond bookes, ballads, rhimes, and other lewd treatises in the English tongue.” — from ‘The ballads & songs of Derbyshire’, 1867.

Having divested the bull-running to Uttoxeter, it may be that the later lords of Tutbury quietly re-established the tradition of the Court alone, and with a better class of bard and piper. Because Dugdale remarked in 1819 (The New British Traveller, Vol 4) that… “An annual court, called the Minstrel’s, continues to be held at the steward’s house” at Tutbury.

One can note that the Tutbury Court tradition continues today with the annual Acoustic Festival of Britain, which takes place on Uttoxeter Racecourse each summer.