Early in the First World War J. R. R. Tolkien had learned to fire a rifle at a camp at Newcastle-under-Lyme, near Stoke-on-Trent. Less well known is that he had a connection with Stoke-on-Trent toward the end of his life, in the period after the first publication and tepid reception of The Lord of The Rings, and before his great work was re-discovered by a critical mass of young readers in the 1970s.

From 1960 through to the early 1970s he spent many holidays with his son — who lived at 104 Hartshill Road, at the top end of Stoke town in Stoke-on-Trent. His son had lived there from 1957, just a few years before his father retired as a university lecturer in 1959. We know, from Tolkien’s surviving published letters, that the senior Tolkien spent the summer of 1960 in Stoke with his son and many summer holidays thereafter. We also know from his letters that he spent winter holidays here, in the early 1970s. Specifically a long late visit at Christmas 1971, after his wife’s death, and a long summer visit in August 1972. His surviving letters don’t provide comprehensive day-to-day coverage of his life, and so there may have been earlier visits to his son in Stoke which went unrecorded. One imagines that Tolkien probably continued to live his life according to the divisions of the academic calendar, as he had since the 1900s, so perhaps some of the holidays were relatively long ones.

Picture: Northcote House, 104 Hartshill Road, seen today. Now converted to a children’s nursery. Presumably the rather bare back-yard, seen here, was once a garden.

Picture: 104 seen from the front, on Google StreetView. Catholic church on the left. Rear upper windows would have given a good view over the city in the valley below.

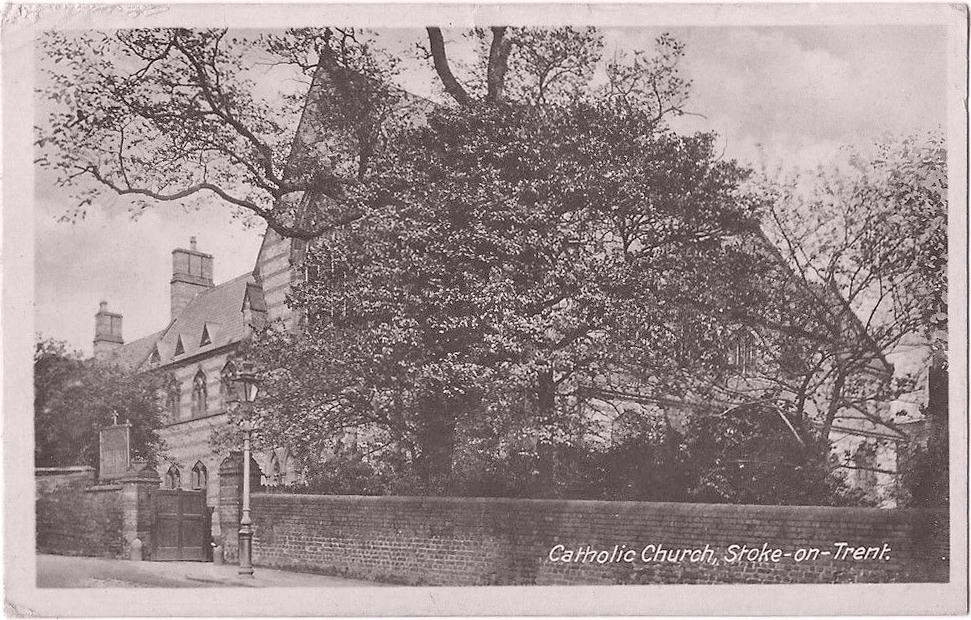

The church where his son was priest, Our Lady of the Angels and St Peter in Chains. Next to it on other side was the large St. Dominic’s Convent and School, and below that the Convent Pools where the girls did Botany studies. This large Catholic school for girls is said to have existed there until 1985.

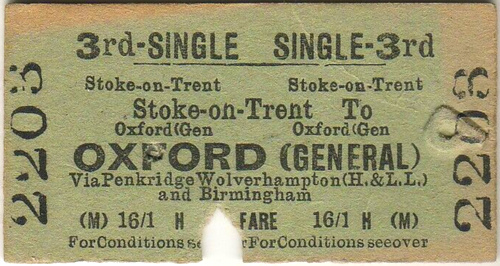

We can thus imagine Tolkien, aged in his late sixties and seventies, being quite familiar with alighting from the Oxford train at Stoke with his trusty bicycle. He disliked cars (“Mordor-gadgets” as he called them), and the car-culture that was everywhere ruining England. Oxford-Stoke is a long-established direct train service, and there’s still a direct two-hour service today. Despite his increasing twinges of arthritis it seems the older Tolkien was still an avid train user and bicyclist and until about 1968 and IRA terrorism it was still fairly easy to get a bicycle onto an inter-city train. Thus we can easily imagine him bicycling from the station through Stoke town (the barrier of the A500 road did not then exist) and up onto the lower slopes of Hartshill. Admittedly, he moved from Oxford to a new home near Bournemouth in 1968 but this would not have hampered a train trip to Stoke. The four-hour journey would then have been Bournemouth to Oxford, and Oxford to Stoke.

Direct train ticket from Oxford to Stoke.

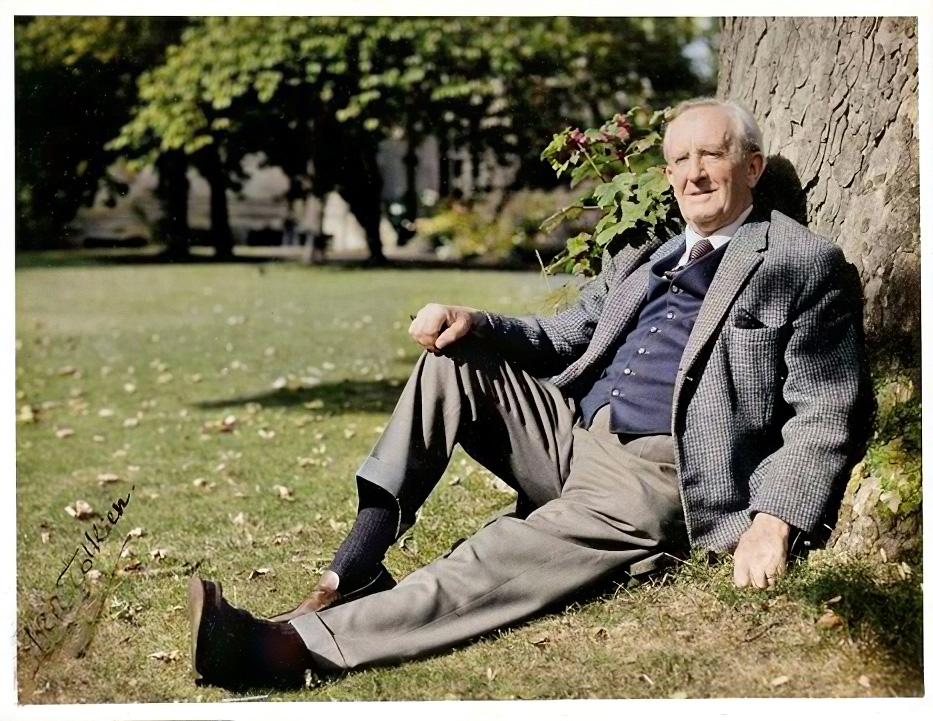

Tolkien as an older man, holding his pipe in one hand, circa 1972.

He was not the cultural colossus he would later become. In 1960 there would be no throng of adoring fans waiting for him at Stoke station, of the sort that might gather today for someone like Neil Gaiman. In Stoke he was just an obscure and rather isolated old man and a retired ‘professor of medieval language and literature’ (as most non-specialists would understand his job). His unwelcome retirement and his caring for his ill wife had tended to cut him off from social life. Yes, he had once published a mildly popular children’s book in 1937, as well as a follow-up fantasy book in three volumes from 1954-56. The children’s book had sold well-enough but not-all-that-well in bookshops, and was out-of-print for most of the 1940s (though there had been a special Children’s Book Club edition, issued in the dark days of 1942). The follow-up had mixed reviews in the press. By the time he was first in Stoke the establishment critics rarely thought of his work, and if they did they usually derided it after a hasty skim-reading, or even no reading at all. Philip Toynbee in the left-wing Observer newspaper (6th August 1961) was pleased to note of Tolkien’s works that… “today these books have passed into a merciful oblivion”. Tolkien’s deep national patriotism and his concern with the heroic past were increasingly out of fashion among the chattering classes of the 1960s and early 70s. What fans his work did have, mostly among the young from about 1966/67 onward in America and from 1968/70 in the UK, tended to see only the surface layer of his stories and he often found such people rather annoying. The cultural seeds that Tolkien had planted in The Lord of the Rings were thus still largely dormant, and they would only grow up into a vast murmuring forest long after his death.

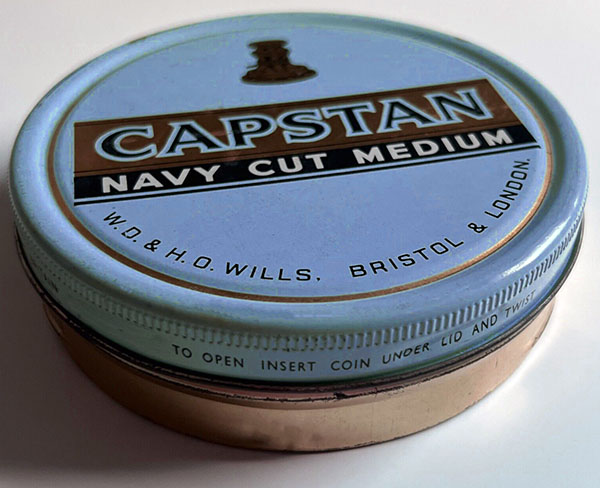

Once unpacked and ‘settled in’ at his son’s house in Stoke, he might have regularly walked or cycled to a local newsagents. Seeking some Capstan Navy Cut ‘Blue’ pipe-tobacco for his very standard Dunhill pipe (sadly he did not sport a Gandalf-ian ‘Churchwarden’ pipe), and a fresh box of matches.

Picture: Tolkien’s preferred pipe-weed. Today referred to as ‘Capstan Navy Cut Ready Rubbed’.

Also some daily newspapers, which were very important to him in terms of keeping him connected to the world. He was in those years an avid newspaper reader, and took both the Times and the Telegraph and read them attentively every day. On these he sometimes liked to doodle fine decorative ‘elvish’ patterns with the newly-invented ‘biro’ pens of red, blue and green. Some of his doodles were exhibited at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, a few years ago now.

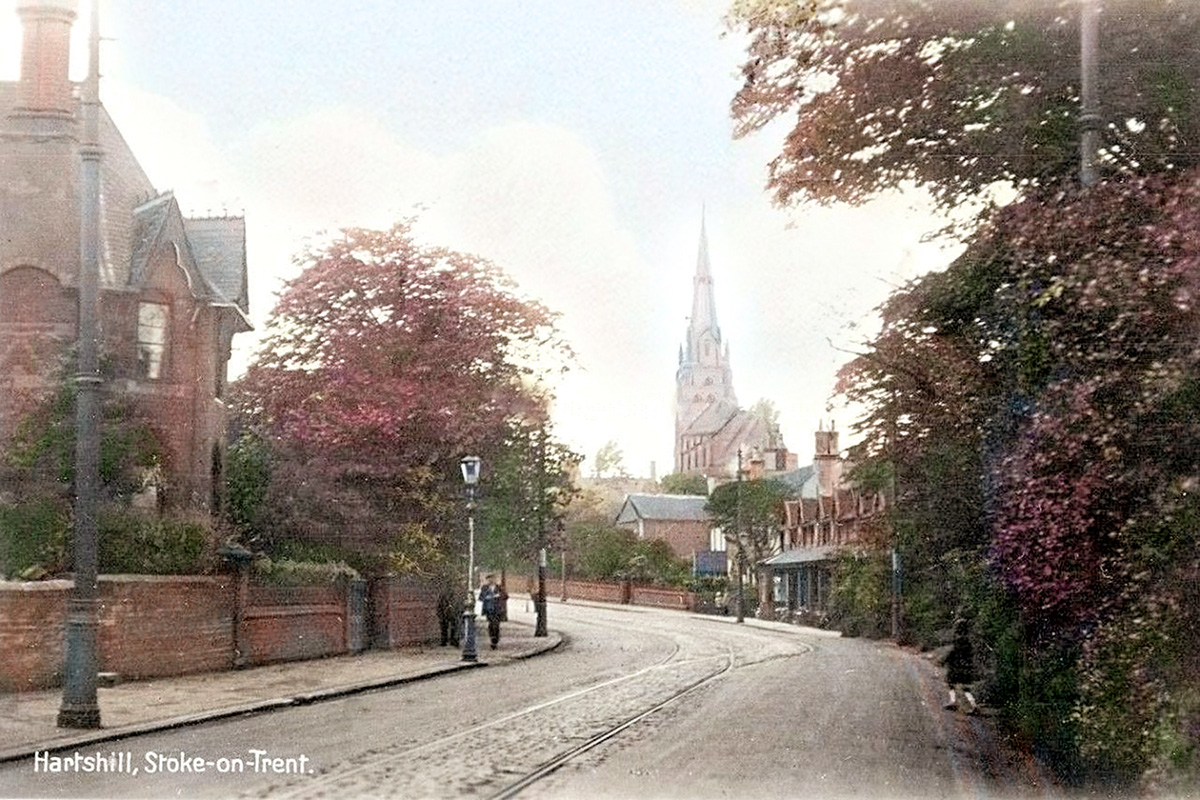

The only route for a probable walk from his son’s home to the centre of Hartshill, the nearest newsagents, pub and Post Office / post-box. Seen here in the 1930s, but much the same until the local Labour Council destroyed the coherence of this part of Hartshill by permitting a modern 1980s petrol station and used-tyres dump.

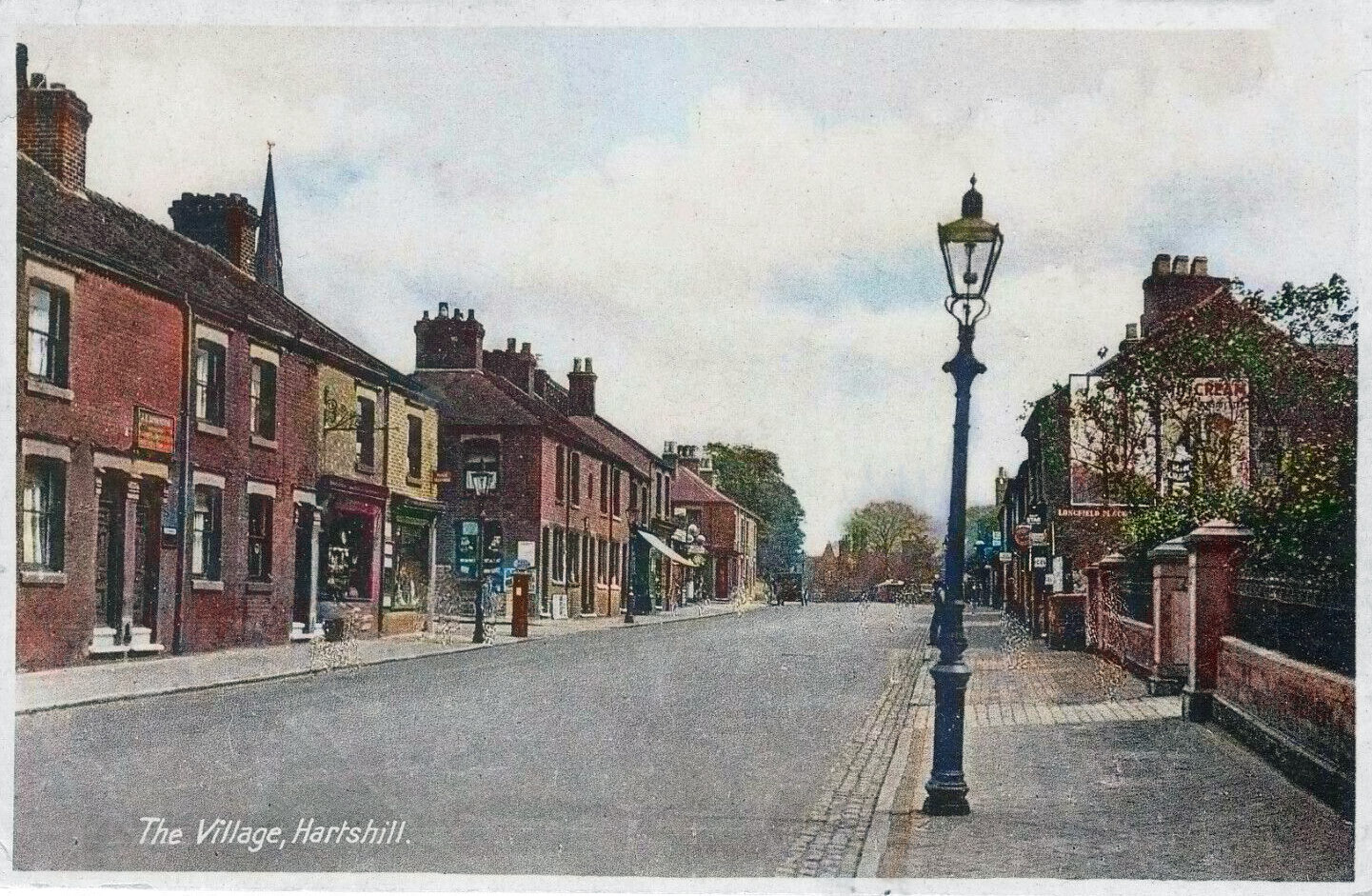

The shops at the centre of Hartshill, a little way up from The Jolly Potters pub and a short walk from where Tolkien was staying. Seen here in the 1930s but much the same in the 1950s-70s, and even today. The most likely local newsagents is in the middle of the picture on the left, with its awning out. On the nearer corner was the nearest Post Office and Royal Mail post-box (still there today).

Quite possibly he visited a local pub for a pint and a smoke of his pipe, the most likely pub being the very nearby Jolly Potters rather than the more work-a-day pubs down in the town. He liked traditional pubs, with good beer and no blaring radio playing music. His memory for everyday matters was by then noticeably declining, but he was still fascinated by the intricacies of language and the names for things. Thus he would have had an eager ear for our strong and distinctive local dialect and words, then far stronger than today’s faded forms.

He would certainly have visited local Catholic churches and places, since he was deeply religious. But where he worshipped in the Potteries is not known. One assumes the church next door to where was was staying, but that might not be the case. Very nearby, at both Burslem and Tunstall, there are very impressive Catholic ‘cathedral’-style churches for instance.

In 1962, he was prize-giver at the Catholic boys’ school of St. Joseph’s in Stoke-on-Trent. This was before the brief ‘Hobbit fever’ of the late 1960s. The end-of-May event was reported in the Catholic Herald on 1st June 1962. We have to assume that he was able to attend the prize-giving because he was staying locally with his son. The school was in Trent Vale, on the London Road, thus Tolkien would likely have walked or cycled down there from Hartshill in the May weather. If so, then we can add the summer of 1962 to the years that Tolkien stayed in Stoke.

St. Joseph’s on the London Road, Stoke.

One imagines that he visited the usual local places on day-trips: the new (opened 1956) city museum, where he might have been more interested in the archaeology and the very fine natural-history rooms, rather than our world-famous ceramics; Trentham Gardens and the richly-wooded parkland estate; Biddulph Grange with its fantastical compartment-gardens and trees; the vast grounds full of trees on the campus at nearby Keele. Apparently the son Tolkien was staying with was, or had recently been (depending on the date) the Catholic Chaplain there. The Keele grounds have fine trees and it later became a formal Arboretum of world class. He would have felt at home in a district that cherished, as he did so ardently, its trees and gardens. Pugin’s Alton Castle in the Staffordshire Moorlands would have been a strong draw for a Catholic. Perhaps he also once or twice waded through the bracken to see King Wulfhere’s hill-fort near Stone, since he had an abiding interest in all things that were early Mercian. Though admittedly such an adventurous and uphill visit might have been too arduous and risky for an older man. If he had visited Wulfhere’s hill-fort and Alton Castle, would he have known how very close he was to his beloved Beowulf and to Sir Gawain respectively? No, sadly he would not have known. The scholarship would have to progress for another sixty years.

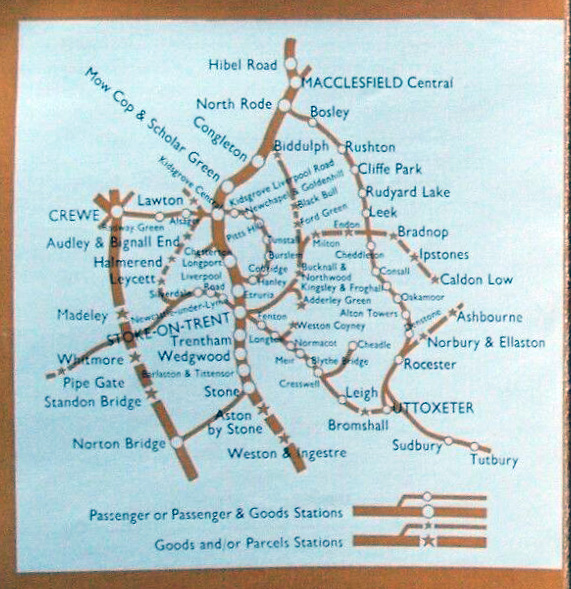

Possibly he and his son liked to use the various bits of the local railway network to get about, since the local lines were fairly extensive until the cuts made by the despised Dr. Beeching in the mid 1960s. His story “Leaf by Niggle”, which features a small railway station at a pivotal point, was written in 1942 and thus cannot have been influenced by the Potteries network.

Pre-Beeching local railway system, at the start of the 1960s.

Any such local visits would of course have been far too late in time to have influenced the landscapes of The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings.

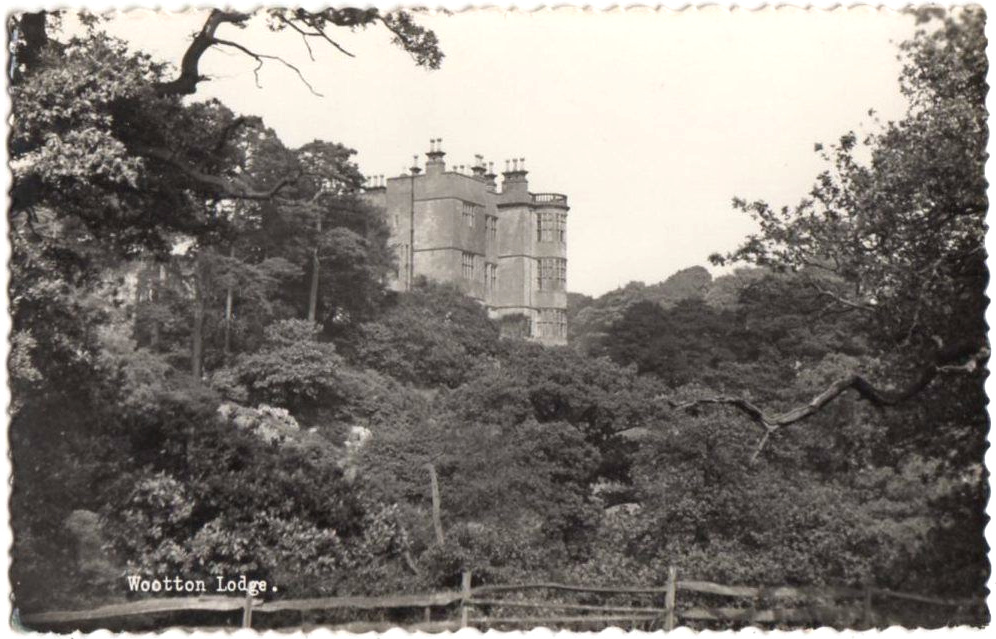

There seems just one possibility for influence on his creative work. In early 1965 Tolkien wrote the bulk of the fine long fairy-story “Smith of Wootton Major”, a late masterpiece which appeared in 1967. One then wonders if the name might come from the elegant house at Wootton near Ellastone, in the moorlands of North Staffordshire.

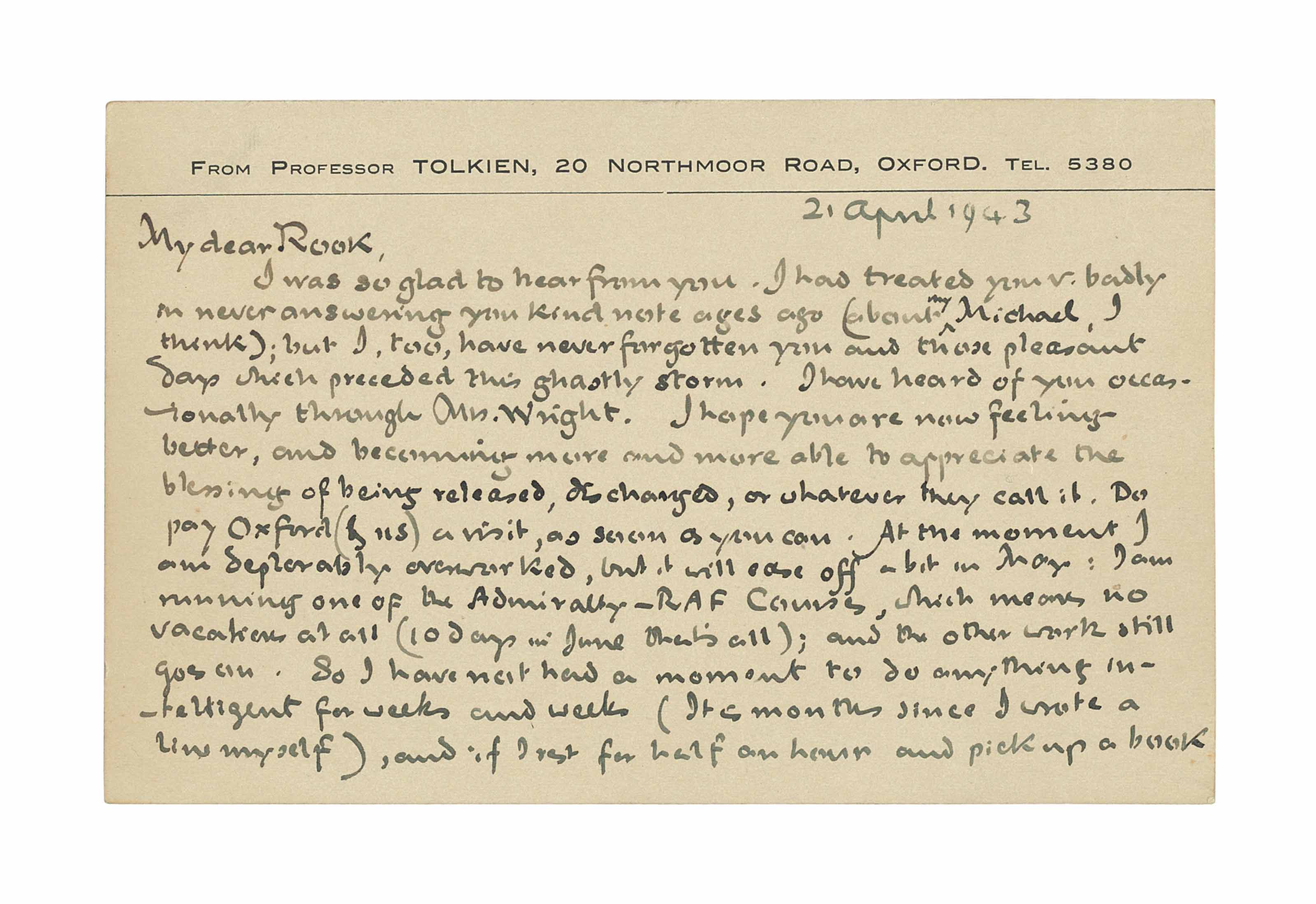

Because, at that time, Wootton was the home of the war poet Major Alan Rook. Rook knew Tolkien, and might have once been his student…

Picture: Wartime postcard from Tolkien to Rook, April 1943. Tolkien assures Rook that he has “never forgotten you and those pleasant days which preceded this ghastly storm”.

Rook had the house from 1950. In 1959 Country Life reported that… “In 1950 the house was bought by the present owner, Major Alan Rook, the poet and playwright, who has solved with great ability and discrimination the problem of living in a house that is both somewhat large and exceedingly remote.” Tolkien’s great friend C.S. Lewis may also have been a visitor at Wootton, as Rook also knew Lewis well (see: Schofield, In search of C.S. Lewis, 1983). Could the ‘Major’ and ‘Wootton’ have then lent their names to the late Tolkien story “Smith of Wootton Major” (published 1967)? This is a very tentative theory, but it gains a little weight if we consider that Tolkien may have mused on the placename ‘Ellastone’ perhaps arising from ‘elf stone’, since this would connect with the matter of the tale. The ‘great house’ setting is also similar.

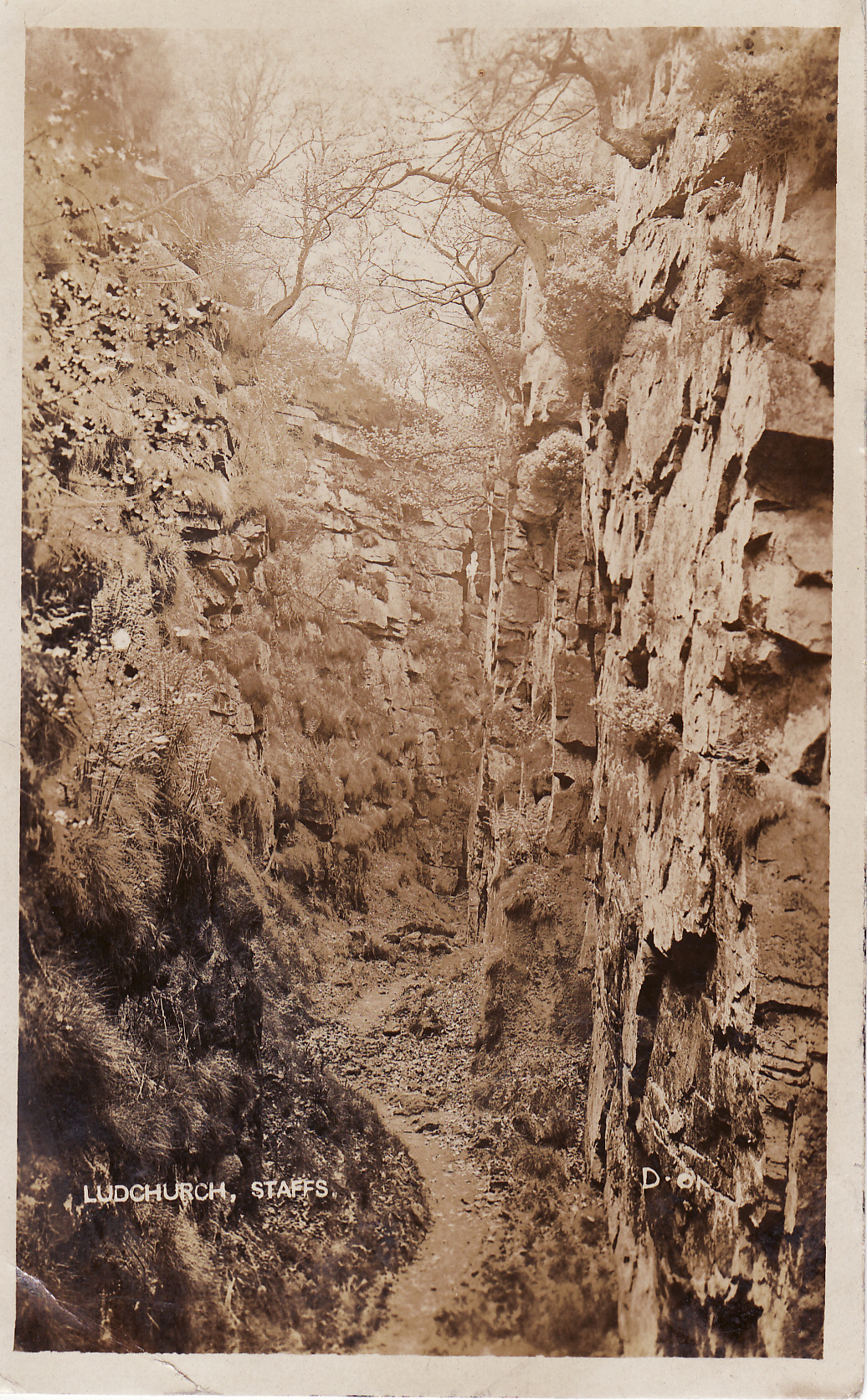

There is also a somewhat less likely influence, but one that is worth considering (if only to dampen the wild claims sometimes heard for it in the Staffordshire Moorlands). Given his continuing scholarly interests it is also conceivable that the older Tolkien made at least one excursion to the eerie cleft of Lud’s Church in the nearby Moorlands, stated nationally in 1958 (R. V. W. Elliot, article in The Times) to be one of the settings for the ancient tale Gawain and The Green Knight — of which Tolkien had published a fine scholarly edition in 1925. Tolkien was still interested in Gawain in his old age. He would broadcast his modern English translation of Gawain on BBC radio in 1953, and would publish his Gawain book again in a revised edition in 1967. Most of the work on the new edition appears to have been done by a student of his, but one then wonders if — as part of the field research for the new edition — Tolkien and his student ever made any trips by car from Stoke into the wild ‘barrow downs’ districts of the Gawain story? These are to be found very nearby, in the Staffordshire Moorlands and on the western edge of the Peak District, only a short car ride away through lovely scenery.

But did he know about such locations when he was younger? Before the writing of The Lord of The Rings, for instance? Well, in the 1925 edition he knew that the fading Gawain manuscript had been preserved by chance in a Yorkshire library, in a copy which was then thought to have been made in south-west Lancashire. However, it cannot be suggested that visits to the Gawain landscape inspired elements of Tolkien’s famous works (such as the road to the Door of the Dead, see postcard above). Since in his 1925 edition of Gawain he and his collaborator could only suggest a broad resemblance of the surviving Gawain copy to old manuscripts known to have been…

“written at Hales in south-west Lancashire, not many years earlier than 1413. This resemblance, however, only goes to show that the dialect of the copyist was of Hales in south-west Lancashire”.

Slightly later, in a 1928 text (Walter E. Haigh’s Glossary of the Dialect of the Huddersfield District) he suggested Gawain was “probably written to the west of Huddersfield”, this being a small district nestled under the northern edge of the Peak District. It was not until later, though, that we have the mature Tolkien stating that the dialect showed that the original author’s…

“home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery.”

By 1928 Serjeantson was suggesting “the western part of Derbyshire”. Much later the dialect specialists would place the Gawain-poet’s likely home-place on the south-west of the Peak and in the precisely described landscape where Gawain meets the Green Knight at the end of the tale, in the northern part of what is now the West Midlands. Most likely an isolated dialect ‘district’ infused with what Tolkien referred to (following the usage of his Oxford tutors) as “Old Mercian” — roughly the North Staffordshire moorlands and the Peak District of western Derbyshire, or just north across the River Dane and the high Cloud into directly-adjacent parts of Cheshire.

We appear to have no other public pronouncements or endorsements of a likely location from Tolkien. Thus, without delving further into what Tolkien thought about Gawain locations, it seems we have no indication that the pre-Lord of the Rings Tolkien associated Lud’s Church or the Moorlands landscape with a Gawain location. It would, however, be interesting for Tolkien scholars to more precisely date the exact point at which Tolkien switched away from his early focus on Lancashire. Could his focus have privately changed on that matter by the early/mid 1940s (perhaps due to Israel Gollancz’s student Mabel Day, who publicly and correctly suggested Wetton Mill in the Staffordshire Moorlands), before he wrote the 'Door of the Dead' sections of The Lord of the Rings? He would have been very remiss, and also very haughty, if he had not bothered to read the key new edition of Gawain in which Day’s statement was made. But if he took note of the suggestion is now unknown.

Further reading:

Tom Shippey, “Tolkien and the West Midlands: The Roots of Romance”, in Roots and Branches: Selected Papers on Tolkien, Walking Tree, 2007. (One of Shippey’s best and most important papers on Tolkien. Originally in Lembas Extra 1995.)

Tom Shippey, “Tolkien and the Gawain-poet”, also to be found in Roots and Branches (2007). (Originally in Mythlore Vol. 21, No.2., Winter 1996, and thus now free online.)

See also my new book Strange Country: Sir Gawain in the moorlands of North Staffordshire. An investigation.

[…] back to Stafford train station then on to Stoke-on-Trent train station. An Uber for a quick look at 104 Hartshill Road in Stoke and perhaps the pleasant back part of the Butts where he learned to shoot live rounds with […]

[…] Moorlands). His son was the Catholic Chaplain at Keele University, and in his retirement he often spent holidays in Stoke-on-Trent — and almost certainly visited Keele Arboretum and the war poet Major Rook who lived nearby […]

[…] A 1963 glimpse of the house Tolkien stayed in when he came to stay in Stoke-on-Trent. […]

Father John Tolkien was Parish Priest first at Knutton, where he was also Keele University Catholic Chaplin, and then at Stoke where Northcote House was the Presbytery near to the church. ‘Professor Tolly’, as the older Tolkien was known to some of his younger friends, frequently stayed with his son at both houses. It was always a joy to see him, when he was staying in North Staffordshire.

Many thanks for the additional information, Shelagh. I wonder if you can recall the framing year dates for his son at Knutton / Stoke? Can you also recall any other details of ‘Professor Tolly’ in Stoke, and date these memories?

[…] Here at Spyders, my “J.R.R. Tolkien in Stoke” blog post has been expanded a bit. Also has some new or better […]

[…] in Stoke-on-Trent. This church is of some tangential Tolkien interest, since the older Tolkien spent many holidays in Stoke-on-Trent in his retirement. His son was the priest there and thus I assume the elder Tolkien attended this […]

[…] “A snippet on Stoke”, adding a new 1962 date to Tolkien’s many visits to the West Midlands city of […]