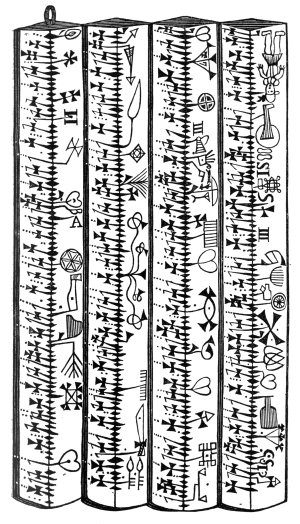

Another bit of memorable local folklore that caught my eye…

From: Abbie Farwell Brown, The Book of Saints and Friendly Beasts (Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1900).

SAINT WERBURGH & HER GOOSE

I.

SAINT WERBURGH was a King’s daughter, a real princess, and very beautiful. But unlike most princesses of the fairy tales, she cared nothing at all about princes or pretty clothes or jewels, or about having a good time. Her only longing was to do good and to make other people happy, and to grow good and wise herself, so that she could do this all the better. So she studied and studied, worked and worked; and she became a holy woman, an Abbess. And while she was still very young and beautiful, she was given charge of a whole convent of nuns and school-girls not much younger than herself, because she was so much wiser and better than any one else in all the countryside.

But though Saint Waerburg had grown so famous and so powerful, she still remained a simple, sweet girl. All the country people loved her, for she was always eager to help them, to cure the little sick children and to advise their fathers and mothers. She never failed to answer the questions which puzzled them, and so she set their poor troubled minds at ease. She was so wise that she knew how to make people do what she knew to be right, even when they wanted to do wrong. And not only human folk but animals felt the power of this young Saint. For she loved and was kind to them also. She studied about them and grew to know their queer habits and their animal way of thinking. And she learned their language, too. Now when one loves a little creature very much and understands it well, one can almost always make it do what one wishes— that is, if one wishes right.

For some time Saint Werburgh had been interested in a flock of wild geese which came every day to get their breakfast in the convent meadow, and to have a morning bath in the pond beneath the window of her cell. She grew to watch until the big, long-necked gray things with their short tails and clumsy feet settled with a harsh “Honk!” in the grass. Then she loved to see the big ones waddle clumsily about in search of dainties for the children, while the babies stood still, flapping their wings and crying greedily till they were fed.

There was one goose which was her favorite. He was the biggest of them all, fat and happy looking. He was the leader and formed the point of the V in which a flock of wild geese always flies. He was the first to alight in the meadow, and it was he who chose the spot for their breakfast. Saint Werburgh named him Grayking, and she grew very fond of him, although they had never spoken to one another.

Master Hugh was the convent Steward, a big, surly fellow who did not love birds nor animals except when they were served up for him to eat. Hugh also had seen the geese in the meadow. But, instead of thinking how nice and funny they were, and how amusing it was to watch them eat the worms and flop about in the water, he thought only, “What a fine goose pie they would make!” And especially he looked at Grayking, the plumpest and most tempting of them all, and smacked his lips. “Oh, how I wish I had you in my frying-pan!” he said to himself.

Now it happened that worms were rather scarce in the convent meadow that spring. It had been dry, and the worms had crawled away to moister places. So Grayking and his followers found it hard to get breakfast enough. One morning, Saint Werburgh looked in vain for them in the usual spot. At first she was only surprised; but as she waited and waited, and still they did not come, she began to feel much alarmed.

Just as she was going down to her own dinner, the Steward, Hugh, appeared before her cap in hand and bowing low. His fat face was puffed and red with hurrying up the convent hill, and he looked angry.

“What is it, Master Hugh?” asked Saint Werburgh in her gentle voice. “Have you not money enough to buy to-morrow’s breakfast?” for it was his duty to pay the convent bills.

“Nay, Lady Abbess,” he answered gruffly; “it is not lack of money that troubles me. It is abundance of geese.”

“Geese! How? Why?” exclaimed Saint Werburgh, startled. “What of geese, Master Hugh?”

“This of geese, Lady Abbess,” he replied. “A flock of long-necked thieves have been in my new- planted field of corn, and have stolen all that was to make my harvest.” Saint Werburgh bit her lips.

“What geese were they?” she faltered, though she guessed the truth.

“Whence the rascals come, I know not,” he answered, “but this I know. They are the same which gather every morning in the meadow yonder. I spied the leader, a fat, fine thief with a black ring about his neck. It should be a noose, indeed, for hanging. I would have them punished, Lady Abbess.”

“They shall be punished, Master Hugh,” said Saint Werburgh firmly, and she went sadly up the stair to her cell without tasting so much as a bit of bread for her dinner. For she was sorry to find her friends such naughty birds, and she did not want to punish them, especially Grayking. But she knew that she must do her duty.

When she had put on her cloak and hood she went out into the courtyard behind the convent where there were pens for keeping doves and chickens and little pigs. And standing beside the largest of these pens Saint Werburgh made a strange cry, like the voice of the geese themselves,—a cry which seemed to say, “Come here, Grayking’s geese, with Grayking at the head!” And as she stood there waiting, the sky grew black above her head with the shadowing of wings, and the honking of the geese grew louder and nearer till they circled and lighted in a flock at her feet.

She saw that they looked very plump and well-fed, and Grayking was the fattest of the flock. All she did was to look at them steadily and reproachfully; but they came waddling bashfully up to her and stood in a line before her with drooping heads. It seemed as if something made them stay and listen to what she had to say, although they would much rather fly away.

Then she talked to them gently and told them how bad they were to steal corn and spoil the harvest. And as she talked they grew to love her tender voice, even though it scolded them. She cried bitterly as she took each one by the wings and shook him for his sins and whipped him—not too severely. Tears stood in the round eyes of the geese also, not because she hurt them, for she had hardly ruffled their thick feathers; but because they were sorry to have pained the beautiful Saint. For they saw that she loved them, and the more she punished them the better they loved her. Last of all she punished Grayking. But when she had finished she took him up in her arms and kissed him before putting him in the pen with the other geese, where she meant to keep them in prison for a day and a night. Then Grayking hung his head, and in his heart he promised that neither he nor his followers should ever again steal anything, no matter how hungry they were. Now Saint Werburgh read the thought in his heart and was glad, and she smiled as she turned away. She was sorry to keep them in the cage, but she hoped it might do them good. And she said to herself, “They shall have at least one good breakfast of convent porridge before they go.”

Saint Werburgh trusted Hugh, the Steward, for she did not yet know the wickedness of his heart. So she told him how she had[60] punished the geese for robbing him, and how she was sure they would never do so any more. Then she bade him see that they had a breakfast of convent porridge the next morning; and after that they should be set free to go where they chose.

Hugh was not satisfied. He thought the geese had not been punished enough. And he went away grumbling, but not daring to say anything cross to the Lady Abbess who was the King’s daughter.

II.

SAINT WERBURGH was busy all the rest of that day and early the next morning too, so she could not get out again to see the prisoned geese. But when she went to her cell for the morning rest after her work was done, she sat down by the window and looked out smilingly, thinking to see her friend Grayking and the others taking their bath in the meadow. But there were no geese to be seen! Werburgh’s face grew grave. And even as she sat there wondering what had happened, she heard a prodigious[61] honking overhead, and a flock of geese came straggling down, not in the usual trim V, but all unevenly and without a leader. Grayking was gone! They fluttered about crying and asking advice of one another, till they heard Saint Werburgh’s voice calling them anxiously. Then with a cry of joy they flew straight up to her window and began talking all together, trying to tell her what had happened.

“Grayking is gone!” they said. “Grayking is stolen by the wicked Steward. Grayking was taken away when we were set free, and we shall never see him again. What shall we do, dear lady, without our leader?”

Saint Werburgh was horrified to think that her dear Grayking might be in danger. Oh, how that wicked Steward had deceived her! She began to feel angry. Then she turned to the birds: “Dear geese,” she said earnestly, “you have promised me never to steal again, have you not?” and they all honked “Yes!” “Then I will go and question the Steward,” she continued, “and if he is guilty I will punish him and make him bring Grayking back to you.”

The geese flew away feeling somewhat comforted, and Saint Werburgh sent speedily for Master Hugh. He came, looking much surprised, for he could not imagine what she wanted of him. “Where is the gray goose with the black ring about his neck?” began Saint Werburgh without any preface, looking at him keenly. He stammered and grew confused. “I—I don’t know, Lady Abbess,” he faltered. He had not guessed that she cared especially about the geese.

“Nay, you know well,” said Saint Werburgh, “for I bade you feed them and set them free this morning. But one is gone.”

“A fox must have stolen it,” said he guiltily.

“Ay, a fox with black hair and a red, fat face,” quoth Saint Werburgh sternly. “Do not tell me lies. You have taken him, Master Hugh. I can read it in your heart.” Then he grew weak and confessed.

“Ay, I have taken the great gray goose,” he said faintly. “Was it so very wrong?”

“He was a friend of mine and I love him dearly,” said Saint Werburgh. At these words the Steward turned very pale indeed.

“I did not know,” he gasped.

“Go and bring him to me, then,” commanded the Saint, and pointed to the door. Master Hugh slunk out looking very sick and miserable and horribly frightened. For the truth was that he had been tempted by Grayking’s fatness. He had carried the goose home and made him into a hot, juicy pie which he had eaten for that very morning’s breakfast. So how could he bring the bird back to Saint Werburgh, no matter how sternly she commanded?

All day long he hid in the woods, not daring to let himself be seen by any one. For Saint Werburgh was a King’s daughter; and if the King should learn what he had done to the pet of the Lady Abbess, he might have Hugh himself punished by being baked into a pie for the King’s hounds to eat.

But at night he could bear it no longer. He heard the voice of Saint Werburgh calling his name very softly from the convent, “Master Hugh, Master Hugh, come, bring me my goose!” And just as the geese could not help coming when she called them, so he felt that he must go, whether he would or no. He went into his pantry and took down the remains of the great pie. He gathered up the bones of poor Grayking in a little basket, and with chattering teeth and shaking limbs stole up to the convent and knocked at the wicket gate.

Saint Werburgh was waiting for him. “I knew you would come,” she said. “Have you brought my goose?” Then silently and with trembling hands he took out the bones one by one and laid them on the ground before Saint Werburgh. So he stood with bowed head and knocking knees waiting to hear her pronounce his punishment.

“Oh, you wicked man!” she said sadly. “You have killed my beautiful Grayking, who never did harm to any one except to steal a little corn.”

“I did not know you loved him, Lady,” faltered the man in self-defense.

“You ought to have known it,” she returned; “you ought to have loved him yourself.”

“I did, Lady Abbess,” confessed the man. “That was the trouble. I loved him too well—in a pie.”

“Oh, selfish, gluttonous man!” she exclaimed in disgust. “Can you not see the beauty of a dear little live creature till it is dead and fit only for your table? I shall have you taught better. Henceforth you shall be made to study the lives and ways of all things which live about the convent; and never again, for punishment, shall you eat flesh of any bird or beast. We will see if you cannot be taught to love them when they have ceased to mean Pie. Moreover, you shall be confined for two days and two nights in the pen where I kept the geese. And porridge shall be your only food the while. Go, Master Hugh.”

So the wicked Steward was punished. But he learned his lesson; and after a little while he grew to love the birds almost as well as Saint Werburgh herself.

But she had not yet finished with Grayking. After Master Hugh had gone she bent over the pitiful little pile of bones which was all that was left of that unlucky pie. A tear fell upon them from her beautiful eyes; and kneeling down she touched them with her white fingers, speaking softly the name of the bird whom she had loved.

“Grayking, arise,” she said. And hardly had the words left her mouth when a strange thing happened. The bones stirred, lifted themselves, and in a moment a glad “Honk!” sounded in the air, and Grayking himself, black ring and all, stood ruffling his feathers before her. She clasped him in her arms and kissed him again and again. Then calling the rest of the flock by her strange power, she showed them their lost leader restored as good as new.

What a happy flock of geese flew honking away in an even V, with the handsomest, grayest, plumpest goose in all the world at their head! And what an exciting story he had to tell his mates! Surely, no other goose ever lived who could tell how it felt to be made into pie, to be eaten and to have his bones picked clean by a greedy Steward.

This is how Saint Werburgh made lifelong friendship with a flock of big gray geese. And I dare say even now in England one of their descendants may be found with a black ring around his neck, the handsomest, grayest, plumpest goose in all the world. And when he hears the name of Saint Werburgh, which has been handed down to him from grandfather to grandson for twelve hundred years, he will give an especially loud “Honk!” of praise.

My notes:

The above story originally appeared in the Acta Sanctorum, with a lost version in the Vita S. Amelberga. Also in Goscelin’s Life of St Waerburh. The name “greyking” (used above) seems to have been a Victorian confabulation.

William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Pontificum Anglorum (early 1100s) says of the location of the story that…

“Waerburg had land in the country beyond the walls of Chester whose crops were being preyed upon by wild geese. The bailiff in charge [unknown name] did all he could to drive them away, but with little success. So, one day, when he was in attendance on his mistress, he put in a complaint about the matter. ‘Go,’ she said, ‘and shut them all up indoors.’ When he realised she was not joking, he went back to the crops and laid down the law in a loud voice: they must follow him as his lady commanded. They formed a flock, lowered their necks, trooped after their foe, and were all penned up. The bailiff took the opportunity to have one of them for supper. At dawn came the virgin. She reproached the birds for stealing things that did not belong to them, and told them to be gone. But the birds, sensing that not all of them are present, refused to make move. God inspired her to realize that the birds were not making all this fuss for nothing, so she closely questioned the bailiff and discovered the theft. She told him to assemble the goose’s bones and bring them to her. At a healing gesture of her hand, skin and flesh immediately formed on the bones, and the skin began to sprout feathers; then the bird came to life and after a preliminary jump launched itself into the sky.”

Despite this Cheshire location, the story seems to have later been appropriated by the East Midlands, specifically by Weedon Bee where Waerburg was Abbess later in her life. There is quite a tedious history to be found in the tug-of-war around the “moving” of relics associated with her, and the moving of the site of the goose legend is perhaps a literary aspect of that. The tale has also been retold in modern times in the book Folk Tales of the East Midlands (1954).

The one misericord unique to Chester Cathedral choir-stalls is of this goose “Miracle of St Werburg” story.

Her goose imagery passed into medieval iconography, specially as a five-goose pilgrimage emblem…

“St Werburgh’s main emblem in medieval iconography was the goose. She is supposed to have restored five of these to life: David Hugh Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Oxford, 1987), 434; The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford, 1990), 273, 1466″ — from Alex Bruce, The Cathedral ‘open and free’: Dean Bennett of Chester. Liverpool University Press.

The goose emblem perhaps throws new light on the meaning of the now-lost stone carvings on the Minster at Stoke town (the Saxon ruins of which can still be seen in the grounds of the new Minster). We know — from inspections carried out shortly before demolition in 1826 — that the old Saxon stone church at Stoke had a large carved swan or goose above its south door, and some other web-footed bird above the north door. Sadly, the heavily eroded webbed feet were all that remained above the north door, by the time someone wrote about it (see: p.463 of The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent by John Ward). The site of the church is at the meeting point of the young River Trent and the Fowlea, an obvious habitat for water-birds.

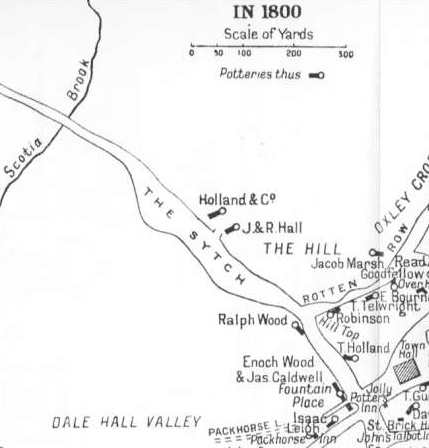

For more discussion of the local folklore of waterfowl, see my History of Burslem & the Fowlea Valley.