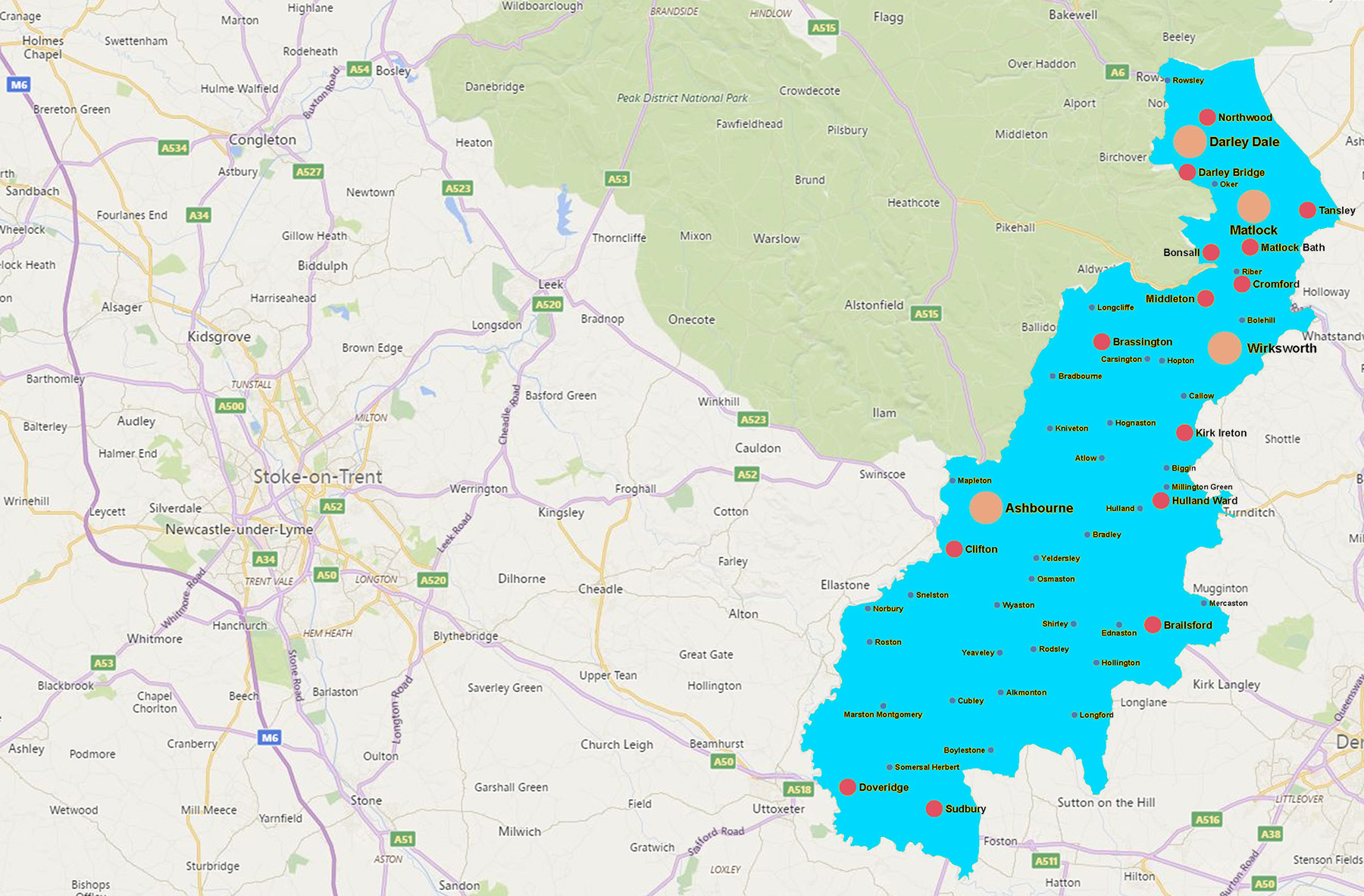

Another local author, found. Kineton Parkes (1865-1938) was a Birmingham man from Aston, who from 1891 to 1911 was curator and principal of the Nicholson Institute in Leek. He was also was the manager-actor of the Leek Amateur Operatic Society for 1899, and generally appears to have been a leading light of the town’s cultural life.

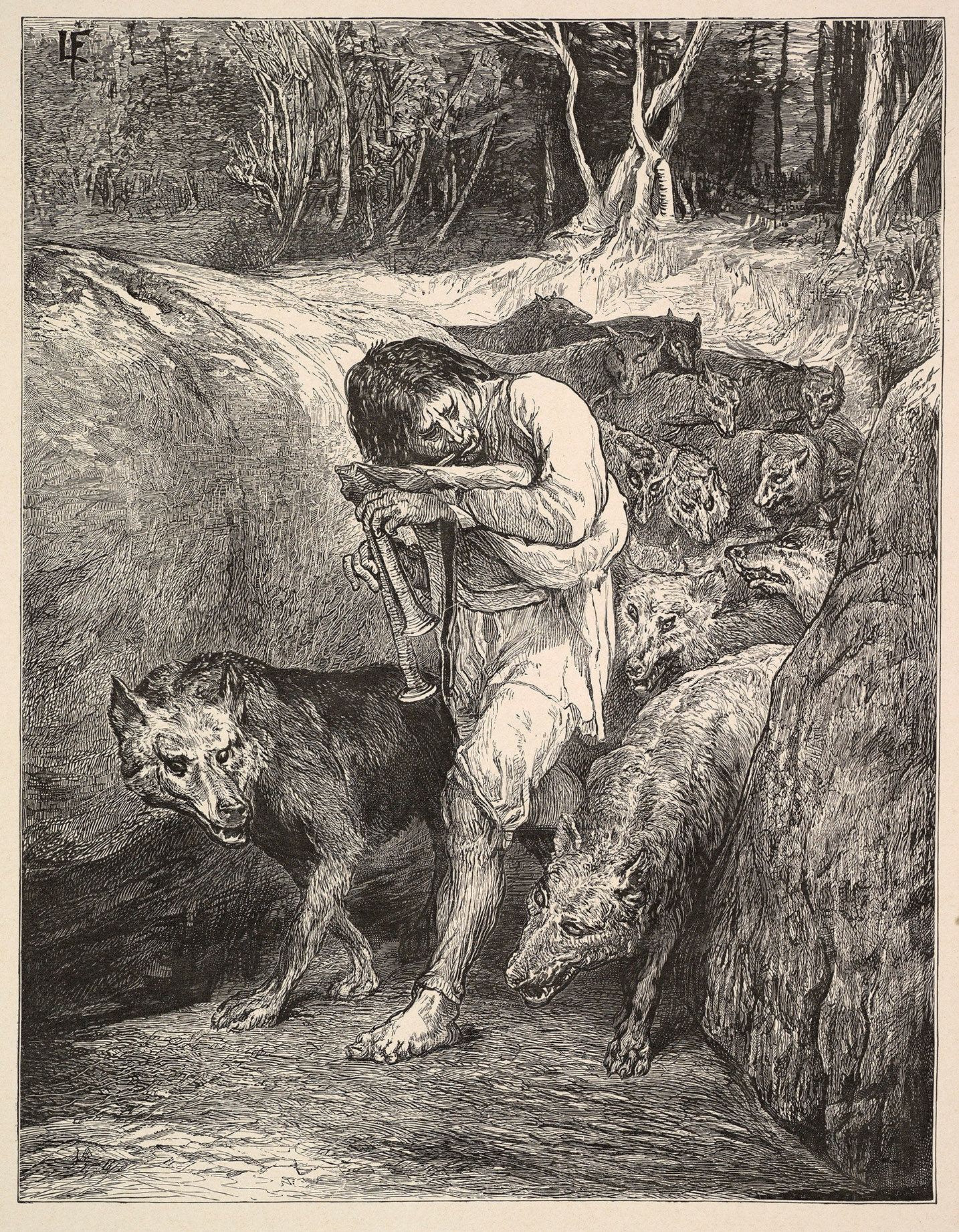

During this time he developed an interest in walking and thus naturally encountered the Roaches, Morridge and the Manifold Valley. This led to his Potiphar’s Wife (1908), a novel of farm life in the Moorlands/Peak and with a good deal of dialect. Apparently it was set circa the ‘hungry’ 1840s and the economic recession of the time (triggered by natural events which began with a massive volcanic eruption in 1816). In 1911 the novel was developed as a play for the London stage, handled by someone who knew the Staffordshire Moorlands and the dialect, although it probably didn’t have too long a run in London.

* Sunday Review — “Rose Critchlow is a woman of strongly passionate and sensuous temperament. Unlike many beautiful women, it is not the excitement of general admiration, the winning of open homage [that she wants, but rather …]

* Staffordshire Sentinel — “The book is a very thoughtful and artistic novel. […] The author describes two widely different aspects of life with skill and understanding. Mr. Kineton Parkes knows the country in the neighbourhood of the Dove and its curious tributary the Manifold with a thoroughness which is only born of a deep and affectionate interest.”

* The Westminster Review (1908) — “Potiphar’s Wife by Mr. Kineton Parkes, is, without exaggeration, a work of genius instinct with the loves and hates of the dalesfolk.”

* The Lady journal — “A story so powerful, original, so full of vigorous and convincing characterisation and of sheer human interest […] worthy of comparison with Thomas Hardy’s Wessex romances.”

Sadly the novel appears to be utterly lost in terms of ‘online’, though the British Library apparently has a copy, along with the libraries at Oxford and Cambridge.

There was also a North Staffordshire novel called The Money Hunt: A Comedy of Country Houses (1914), which was distinctly more cheery than the tragic Potiphar’s Wife…

“The Money Hunt is one of the last the author wrote before leaving the moorlands of North Staffordshire for Devonshire. The scenery of “The Money Hunt” is that of the moorlands, as was that of Mr. Parkes’s previous novels, full of excellent humour and with illustrations.”

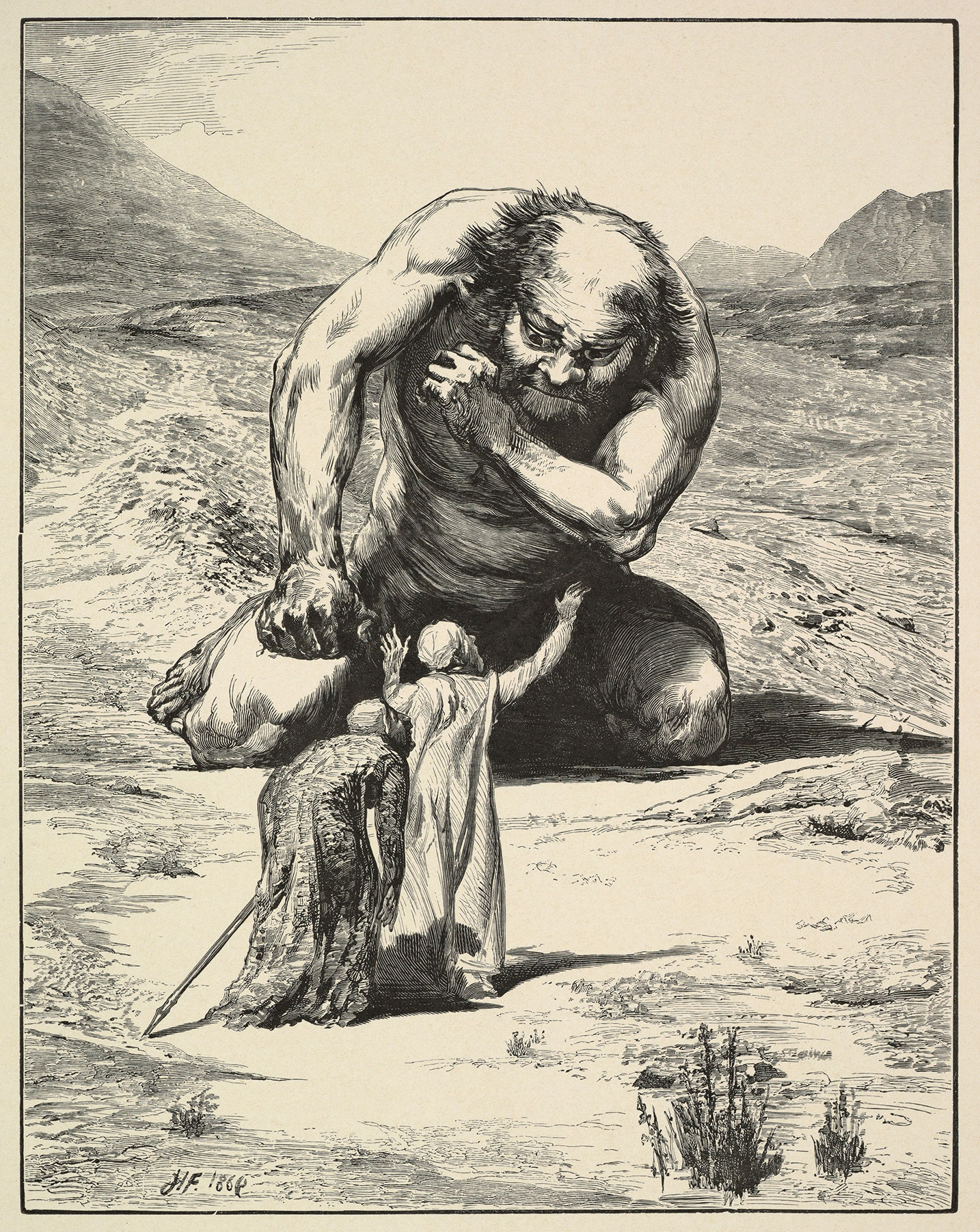

This blurb assumes that his novel The Altar Of Moloch (1911) was also set in the Moorlands. Despite its gruesome title it was apparently not supernatural, but rather “an account of the musical temperament”. The Westminster Review called it…

“a story of four men and a maid, Beautiful Vaudrey Woodrolle who is the only daughter of a ‘cello-playing village schoolmaster. Her wonderful voice so much impresses the Lady Bountiful of the village that she persuades Mr. Woodrolle to send his daughter to Madame Andreini …”

His Moorlands novels are sadly forgotten and unavailable, and if he is remembered today it’s by academics as a Ruskinite and writer of the 1920s on the sculpture and sculptors of the time. His main output was:

Shelley’s Faith: Its Development and Relativity [1888]

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement (non-fiction) [1889]

The Painter-Poets (Editor) (non-fiction) [1890]

The Library Association In Paris (non-fiction) [1893]

The Sutherland Binding (non-fiction) [1900]

A Guild Of Cripples (poetry and short stories?) [1903]

Love a La Mode: A Study in Episodes (short stories on the philosophy of love) [1907]

Life’s Desert Way (novel) [1907]

Potiphar’s Wife (novel) [1908]

The Altar Of Moloch (novel) [1911]

The Money Hunt: A Comedy of Country Houses (novel) [1914]

Hardware. A novel in four books (modernist novel?) [1914]

Windylow (novel) [1915]

Sculpture Of To-day (non-fiction, 2 volumes, third volume did not appear) [1921]

Mystery Of Chinese Art (non-fiction) [1929]

The Art Of Carved Sculpture (non-fiction) [1931]

He probably also has a number of uncollected essays on sculpture and sculptors, in art journals such as Apollo.

He was also a magazine editor. Kineton Parkes was editor of the illustrated journal Comus (1888-89). Then while at Leek he was tapped as editor of the short lived Library Review (1892-1893), which rather ambitiously aimed to track and briefly review the entirety of the torrent of new books then being produced. One has a vision of wagon-loads of books being carted to Leek from London on a weekly basis. He was later assistant editor and then editor of the monthly Igdrasil: the Journal of the Ruskin Reading Guild.