A new 2020 M.A. dissertation reconsiders the discounted idea of a monastic authorship for Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in “Revelations in the Green Chapel: The Gawain-poet as Monastic Author”. It is online in open access.

The case for monastic authorship is not at all proven, but the dissertation’s discussion still makes for interesting reading. The author draws on Philip F. O’Mara (1992) who proposed that one Robert Holcot could have been a possible tutor for the young Gawain-poet. This is compatible with the timeline in my recent book and indeed fits it quite nicely. O’Mara’s short article looked at themes and symbolism and suggested that the Gawain-poet clearly…

“knew the Moralitates [by Holcot], and perhaps Holcot’s more professional works.”

O’Mara then makes a leap. He suggests that, to know Holcot’s work and his thinking, the Gawain-poet likely had some personal tuition under Holcot…

“If he was born between about 1310 and 1330 [he may have become, personally] “Holcot’s student (perhaps informally) … more probably at Northampton [re:] Holcot’s work in Northampton in his last years.”

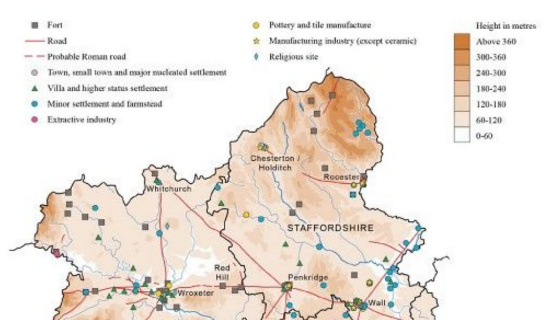

The dates do match mine very well. Robert Holcot left the service of the rather liberal-sounding Bishop of Durham in 1342, and after (perhaps, maybe) a series of winter lectures at Cambridge Holcot was assigned c. 1343 to serve with a Dominican religious house in Northampton. These dates would be a perfect fit for a then 16-18 year-old Gawain-poet, boarded with a suitable lesser house and educated locally when young as was the custom (Swythamley, in relation to Alton?), but then in need of some further tuition and polishing for a year or so. The intellectual dispositions of both the Bishop of Durham and Holcot also fit very well with the concerns and approaches of Gawain.

There is the question, though, of to what extent Moralitates was “published” in 1340. And, if then widely distributed and digested by c. 1342, could it then have been taken up for use in teaching by other personal tutors and abbots of the time? But perhaps the most likely explanation is simply that the Gawain-poet closely read and absorbed Holcot’s works at some time between 1342 and 1376.