Twelve ‘lost things’ from Stoke:

1. Aurochs. Giant prehistoric wild cattle which survived to the Roman period, a skull of which was discovered in diggings at Etruria and is in the Potteries Museum.

2. The old Roman Road, through Wolstanton to where the current Stoke train station is. Though some of Rykeneld Street is likely still there, underground.

3. ‘The Lost Painting of Longton’. Robert Bateman’s large major oil painting “Saul and the Witch of Endor” was given to the city and was last heard of in Longton Town Hall in the early 1950s.

4. The vanished railway line from Stoke railway station to Newcastle-under-Lyme, which went through over 700 yards of tunnels to get there and went on the town of Market Drayton. Also the Potteries Loop Line around the city, though much of that now survives as off-road bicycle paths.

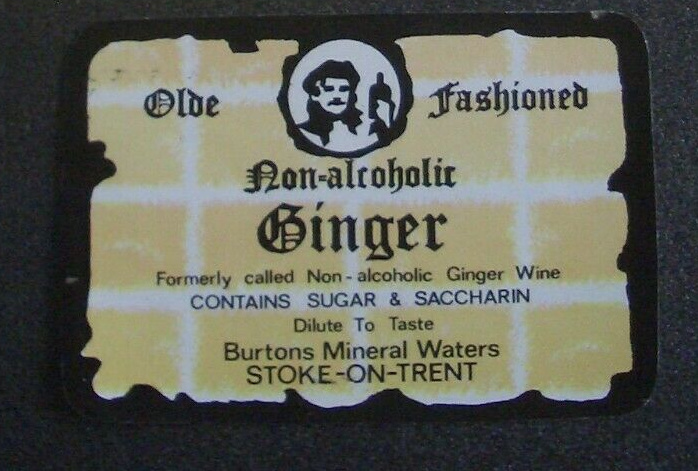

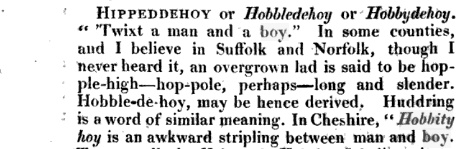

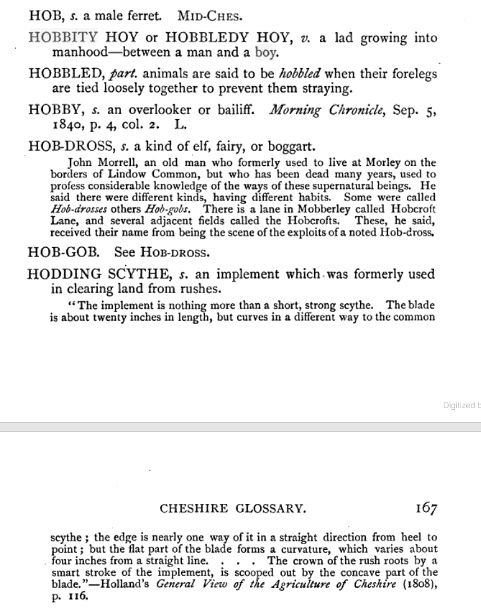

5. The old-style ‘very broad’ Potteries Dialect, now almost extinct.

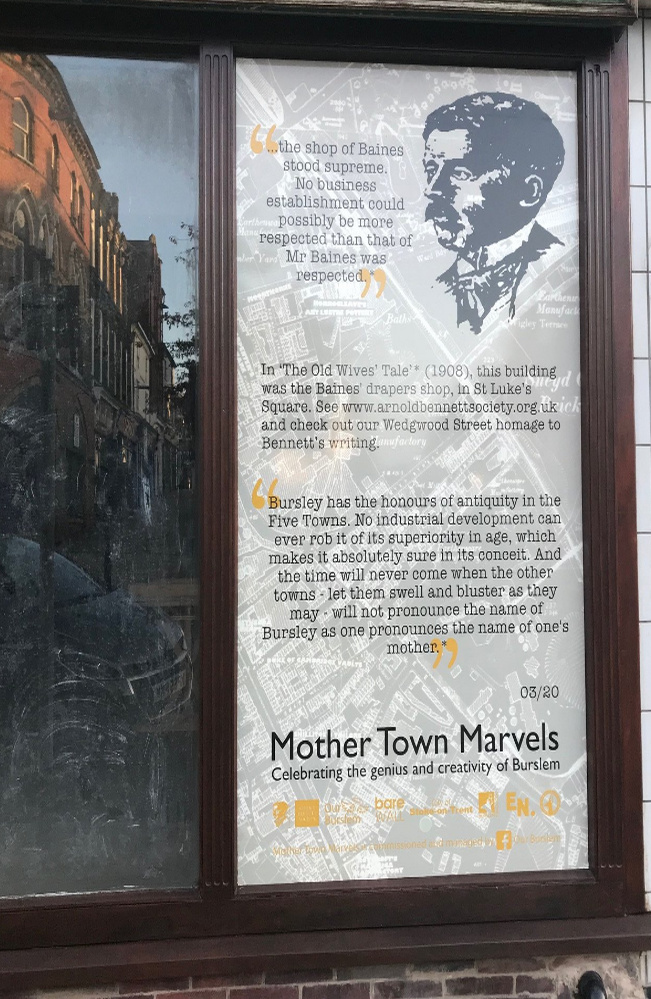

6. The Etruria Woods, of which only remnants and re-growths now remain. One might also include the vast 55-mile long Lyme barrier-forest from the Norman era, which gave its name to Burslem.

7. The vast network of modern deep-mining tunnels. Now flooded, they run mostly from around Forest Park across the valley to Wolstanton.

8. Trentham Hall, offered to the Council as a miners’ hospital but unwanted and thus largely demolished. But the Gardens and Estate are now thriving.

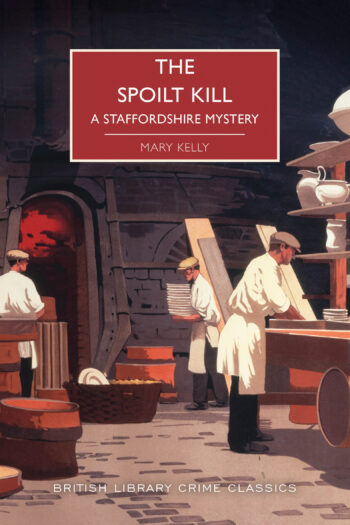

9. Wedgwood’s secret glazes, for making pottery. When H.G. Wells was living in the Potteries, he roomed with a school-fellow who had the job of trying to reconstruct these secrets from the old dried-out glaze-pots in the cellars of Etruria Hall.

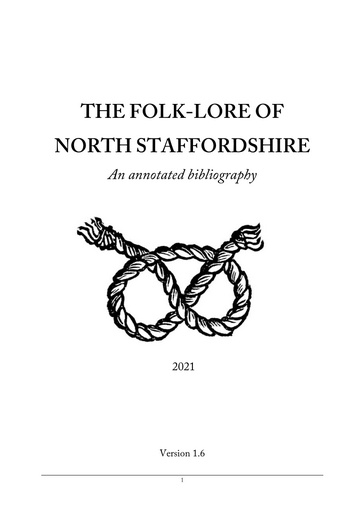

10. Folklore and old local tales, of which only fragments remain. Also related customs, such as the annual Hanley Venison Feast.

11. The North Staffordshire Field Club. Once one of the largest and well-patronised in the nation, with amateurs researching everything from local history and geology to local insects and birds. Like a burst seed-pod, it eventually withered away after giving life to a great many individual specialist groups.

12. The Trubshaw Cross at Longport. In the 1620s said to be the terminus of “a great passage out of the north parts unto diverse market towns”, serving the packhorse teams that bore the industries of the Peak (sheep-fleeces, metals etc) to Newcastle-under-Lyme and thence to the good roads that ran north and south. By the 1840s only the stone base of the cross, likely of “Saxon origin”, remained.