Some Staffordshire sections from Tobias Churton’s book The Magus of Freemasonry: the mysterious life of Elias Ashmole, scientist, alchemist, and founder of the Royal Society…

Following the Royalist defeat at Worcester in July 1646, Parliamentary officers ordered Elias Ashmole to keep out of London […] he returned to the area of Shallowford in Staffordshire, near the Bishop of Lichfield’s palace at Eccleshall, about twenty miles northwest of [his home place of] Lichfield.

Ashmole was a friend of Izaak Walton [who was of like mind, and had retreated to the same area …] They were certainly friends by the time of the 1676 edition of Walton’s world-famous The Compleat Angler … To those who are familiar with his references, Walton’s work, apparently devoted to the harmless pastime of angling, reads like a covert message to depressed Royalists and dispossessed Anglican clergymen throughout the country. […] The book’s message can be read as “Be calm, contemplate the waters;

receive inspiration therefrom: all troubles will pass.” Or, as Walton himself recommended, “Study to be quiet.”

The “troubles” referred to by Walton derived from the puritanical, repressive, anti-ecclesiastical, and generally hot-headed manifestations of Cromwell’s [Puritan] government. […] In his letter to Barlow, Walton notes that he is himself “not suspected,” to the extent that he can even attend a “fanaticall meeting” of Puritanical activists […] The violence [of the Puritans] extended beyond stones, lead roofs, and church bells. [This point refers to the fact that the puritans were busy destroying Lichfield cathedral with its three magnificent spires]. On August 2, 1652, Ashmole went “to heare the Witches tryed, and tooke Mr Tradescant with me.” […] In the event, six witches were hanged […]

[Returning from the trials] On August 19, 1652, Ashmole “entered Lichfield about sunset.” Against the reddish skyline he would have seen the silhouettes of two spires, the third truncated at its base, having crashed through the roof. According to local historian Howard Clayton’s Loyal and Ancient City, after the Parliamentarian destruction of 1646, “Centuries of religious custom disappeared and the Cathedral Close became for 14 years a place of ruin, inhabited by squatters and haunted by owls at night.”

On September, Ashmole “took a Journey into the Peake [Peak District], in search of Plants and other Curiosities.” Ashmole’s “Noates”* of his journey contain short entries of peculiar words, sayings, rhymes, miners’ language and customs, cookery recipes, people, inscriptions, and sights. For example, a Staffordshire oatcake was called a “Bannock” consisting of oatmeal and barley, baked on a griddle. “A Spider is called an Aldercrop.” [a folk preservation of the Old English word at(t)orcoppa and the Middle English attercop]

He mentions a man called “Wagge” from the moorland village of Wetton who “is Staffordshire Astrologus,” a fellow astrologer. At Dove Bridge (near Uttoxeter), Ashmole actually participated in a magical “Call,” or invocation of spirits. “I came to Mr: Jo: Tompson, who dwells neare Dove Bridge. He used a Call, and had responses in a soft voyce.” Ashmole inquired of the spirit concerning the health of his friend Dr. Thomas Wharton, who was poorly. “He told me Dr: Wharton was recovering from his sickness, and so it proved.”

Incidentally, at nearby Great Haywood, Tolkien later caught a similar spirit-of-place. As he stood on the long bridge there, listing to the “wistful murmuring” of possibly-spirits beneath it (Lost Tales II).

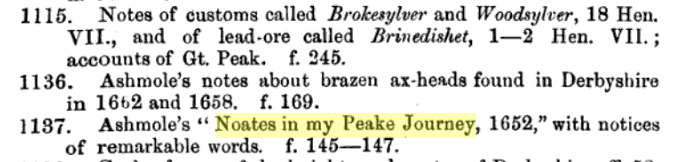

* – “Noates in my Peake Journey“, printed in the five volume Elias Ashmole, 1617-92, aka Elias Ashmole: His Autobiographical and Historical Notes. Vol. 2 seems to be the target that contains the “Noates in my Peake Journey“. Archive.org has another volume, but Vol. 2 is not there or on Hathi. The hardback set only has one library copy for the whole of the UK university system.

There are three “Noates” of interest according to The Antiquary via Google Books. None has been digitized and placed online by the Bodleian.

Ashmole MS 1137 is said to be a copy by an engraver, the original being lost.