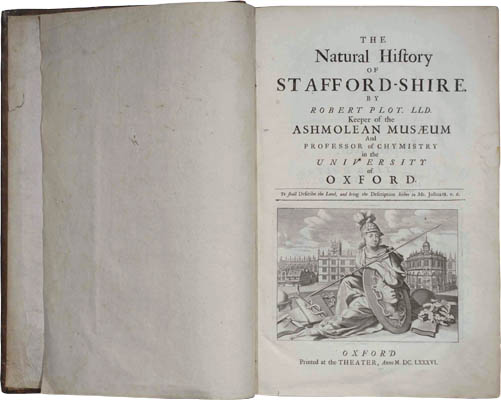

Robert Plot’s The natural history of Stafford-shire is now publicly available online, albeit in OCR and seemingly without pictures.

Robert Plot’s The natural history of Stafford-shire is now publicly available online, albeit in OCR and seemingly without pictures.

A fascinating account of the survival of an archaic Staffordshire and Cheshire word, tallet, meaning the hay-loft above a stable. The passage on tallet occurs on page 105-6 of Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore (Oxford University Press, 19131) by Mary Elizabeth Wright. Wright was the learned wife of one of J.R.R. Tolkien’s key tutors at Exeter College Oxford, Joseph Wright.

1. Likely to be November 1913. In October 1913 The Dial stated that the book was forthcoming and to be issued in the Autumn of 1913. In the 1st December 1913 issue of the The Dial, the book is listed as having been “received since the last issue”. Given the delay in transatlantic shipping to the USA, this would place the publication date at perhaps early to mid November 1913. Given the date and the author, and the subject matter (inc. “Supernatural Beings”, plant names etc) it seems a likely early influence on Tolkien. The possible influence has been explored by J. S. Ryan in his essay “An Important Influence: His Professor’s Wife” (in Tolkien’s View: Windows into his World, 2009).

A couple tour a few of the many pottery factory outlets in Stoke-on-Trent, and are generally disappointed by all but Dudson in Burslem…

“Julia thought she’d like to look round a shop full of odds and ends of hotel ware [at Dudson]. So, U-turn [the car] and waste time as traffic builds up. I couldn’t have been more wrong. It’s actually got loads of great (brightly coloured) stuff and it’s cheap. It also had plenty of room for fat people and a cheery woman on the till. I bought more there than we bought anywhere else … We will be going back to Dudson, and will doubtless fit in a visit to Moorcroft [which is nearby]”

I’m generally rather sceptical of ‘place-name evidence’. But it seems that ‘generic’ stream names are, in aggregate, clear evidence of ancient territorial boundaries. Which is a very interesting finding…

One can glimpse here the boundaries of ancient Mercia, the incursion of the Danelaw, and even spot the English speakers who settled into a little nook of Wales. Tolkien was fascinated by that nook, as a linguistic reliquary, and is known to have visited it. In one of his texts he named himself ‘Prof. Rashbold of Pembroke’.

“Tolkien fan science and the flora of Middle-earth“, musing on a just-published Oxford University Press book Flora of Middle-Earth: Plants of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium.

“The book’s thoroughness and detail is exhilarating. Though most of the information it offers can be found in field guides, encyclopedias, and other reference sources, I did not really appreciate the variety of plants Tolkien portrays in his world until I read it. Sated with Tolkien’s love of trees and his obsession with climatic and ecological details, a reader can easily overlook the diversity and careful placement of Middle-earth’s plant-life. Flowers and shrubs are everywhere, from Bagshot Row to Morgul Vale. The biomes of Tolkien’s world show a profound ecological insight, from the First Age through to the Fourth.”

Yet… “it is unlikely to attract many botanists or Tolkienists, much less casual readers. A passion project it proceeds, seemingly without care for an audience, shoring its opinions with insouciance and data.”

Sounds absolutely wonderful. However, on closer perusal on Amazon I definitely don’t like the rather chilly and dour b&w woodcut style of Graham Judd’s illustrations, which doesn’t reflect the warm and enticing cover illustration. Good for researchers, though.

Update: Having seen it I really can’t recommend it for most, due to the choice of interior art style. Vastly better for most people will be the beautiful and warm book The Plants of Middle-earth. Perhaps accompanied, if a gift for a bloke, by Pipe-smoking in Middle-earth.

I just abandoned making a new Wikipedia page, halfway through. It’s such a hassle now, with so many hoops to jump through. Forget it… they won’t be getting any more new pages from me.

“Bodleian Library Publishing (BLP) will release the largest collection of material by J. R. R. Tolkien in a single volume [an illustrated hardback] as a companion to an upcoming exhibition. Tolkien: Maker of Middle Earth launches on 1st June 2018, to coincide with an exhibition of the same name at the Oxford University library.”

Today I heard a passing claim that in the 1950s… “Workers in the Potteries couldn’t expect to live far beyond 50”.

Given the source I suspect this claim must arise from a footnote on page 48 of the oral history book Missuses and Mouldrunners (1988), which had a footnote that “Life expectancy for anyone who survived his or her fifth birthday was an average of forty-six years”. This assertion referenced the local historian J. H. Y. Briggs in his A History of Longton (1982), though the author curiously fails to give a page number for this reference. Nor are dates or a location given, other than that implied by the Longton title of the book.

However, the author of the footnote was obviously talking of the pre-1914 period. Since the Briggs reference is followed by the statement that, across the UK, the 1901-1912 average was “51.5 for men and 55.4 for women” (referencing Gittins, 1982, p. 210). In that case, taking into account the amount of deep coal miners working in North Staffordshire, it looks to me like a pre-1914 Stoke worker who was not a coal miner or in a similarly hazardous occupation might have been likely to be fairly average in terms of their overall UK life expectancy. The national average was then low, admittedly, but improving along with healthcare, nutrition, sunshine exposure, and industrial safety measures.

Further, the full title of Briggs’s 113-page book, issued by the Dept. of Education at Keele, was A History of Longton. Part 1: The Birth of a Community. So it seems likely he was only addressing the early period of Longton, then ‘the worst’ bit of the Potteries. There never seems to have been a “Part 2” book. I’ve been unable to see the book, to see if Briggs used a valid reference for his claim. [Update: now seen at April 2022, see appended section below].

Still, I’ve had a very good look for a source that he might have used, searching among all the major public online resources. Archive.org is a mess to search, these days, but there seems to be a curious lack of data and tables from 1920s-1980s. I also looked on Hathi, Google Books, Scholar etc. From what little I can find, mostly post-1970s, the Potteries district appears to have followed along with the general UK upward rise in good health, usually lagging behind by a decade or so. Presumably, as other areas raced ahead in health, our averages were then dragged down for the obvious reasons in the 1990s and 2000s — such as 1990s deaths among pensioners who had been miners in the 1970s, the inner-city heroin epidemic of 1985-2005, and often poor elderly healthcare (the Stafford hospital scandal and the post-1998 pressure on the NHS etc).

I’m also made suspicious of the claim because academics dealing with demographic matters usually make gender-specific claims such as… “For babies born in 1901, life expectancy was then estimated to be 45 for boys and 49 for girls.” (from Life in Britain: Using Millennial Census Data, 2005). Thus a broad-brush claim that for the Potteries… “Life expectancy for anyone who survived his or her fifth birthday was an average of forty-six years” fails to make the expected gender distinction. The lack of a date-range or page number for the Briggs reference in Missuses and Mouldrunners also adds to the impression of imprecision.

One then has to wonder if Briggs was referring to some specific Longton data (and presumably from the pre-1914 period since that was the topic of his book), and if the imprecision of the reference to Briggs in Missuses and Mouldrunners then allowed his claim to be grabbed and implied to cover the whole of the Potteries?

Sadly there seems to be no chart of actual life expectancy of workers here, from say 1901-1981 (i.e.: prior to the heroin epidemic, and mass retirement of miners). Still less a simple and reliable one. Certainly there appears to be no solid public data on life expectancy in the Potteries at the end of the 1950s, and indeed one might expect that the death-rate in the Second World War would have anyway made the meaningful assembly of such figures impossible.

A claim of “Workers in the Potteries couldn’t expect to live far beyond 50” is anyway highly misleading. Even if the Potteries of the 1950s had actually been stuck at 1900s levels for about 50 years (which is doubtful, given the huge medical and other advances), then age 50 would still have been the average. Some would have lived far longer, a few far less. The phrasing of “Workers in the Potteries couldn’t expect to live far beyond 50” wrongly suggests that nearly everyone dropped dead within a couple of years of their 50th birthday. It seems to be politically convenient modern shorthand for point-scoring, not reliable population science or history.

Further reading: I’ve previously looked at the 1990s life expectancy figures here, and at Marx’s oft-repeated but very shaky 1860s claims here. I’ve also taken a close look at “Air pollution in the Potteries”, including a big study that appears to show that of a “cohort of 7,020 male pottery workers born in 1916-1945” only “47 deaths could be even tentatively tied only to silica dust exposure.” I’ve also looked at claims of past cobalt poisoning among the Potteries workforce.

Here are the 1980-onward life expectancy figures for Stoke-on-Trent, with future projections…

An update in April 2022:

I’ve now been able to see the Briggs book A History of Longton (1985) which is newly on Archive.org in spring 2022. I can thus can check the reference given in the book Missuses and Mouldrunners (1988). This reference is given no page number or date range in Missuses, but is found on page 73 of A History of Longton and the date range is actually 1900…

This is the only occurrence of “life expectancy” in the book. It occurs in reference to over-zealous 1890s truancy inspectors rousting sick and dirty kids out of their homes and into schools, where they were claimed by a local doctor to spread disease. The “48 years” figure given clearly relates to the year 1900 in Longton (as “the first year of the new century”). Though the source for his 1900 data point is not cited. Missuses and Mouldrunners‘s citation of this as “Life expectancy for anyone who survived his or her fifth birthday was an average of forty-six years” is therefore slightly misleading. The lack of precision makes it appear to the reader that life-expectancy figures from the worst bit of Stoke-on-Trent at the end of the 1890s can ‘stand in’ for the whole of the city. They can’t, and this imprecision is presumably what has led to the small local myth I encountered… it allowed a reader to assume that these figures were for the whole city, and then further to elide this into a claim that the city’s overall life expectancy had somehow remained at 1890-1900 ‘Longton levels’ into the 1950s.

For some reason my free Two Universities Way walk booklet / PDF is no longer find-able via Google Search. So I’m re-hosting it here, to see if there’ll be any change. The mostly off-road route takes one from Staffordshire University at Stoke-on-Trent, out to Keele University.

Now free on Archive.org, a 1947 biography of Stoke-on-Trent composer Havergal Brian, Ordeal by Music, from the Oxford University Press.

John Wain’s novel of the post-war ambition and careers of two men, The Contenders (1958) was made into a 1969 ITV drama “set in the Potteries”. 4 x 60-minute episodes according to IMDB. It seems likely that the tapes have not survived, but I wonder if the scripts are still around?