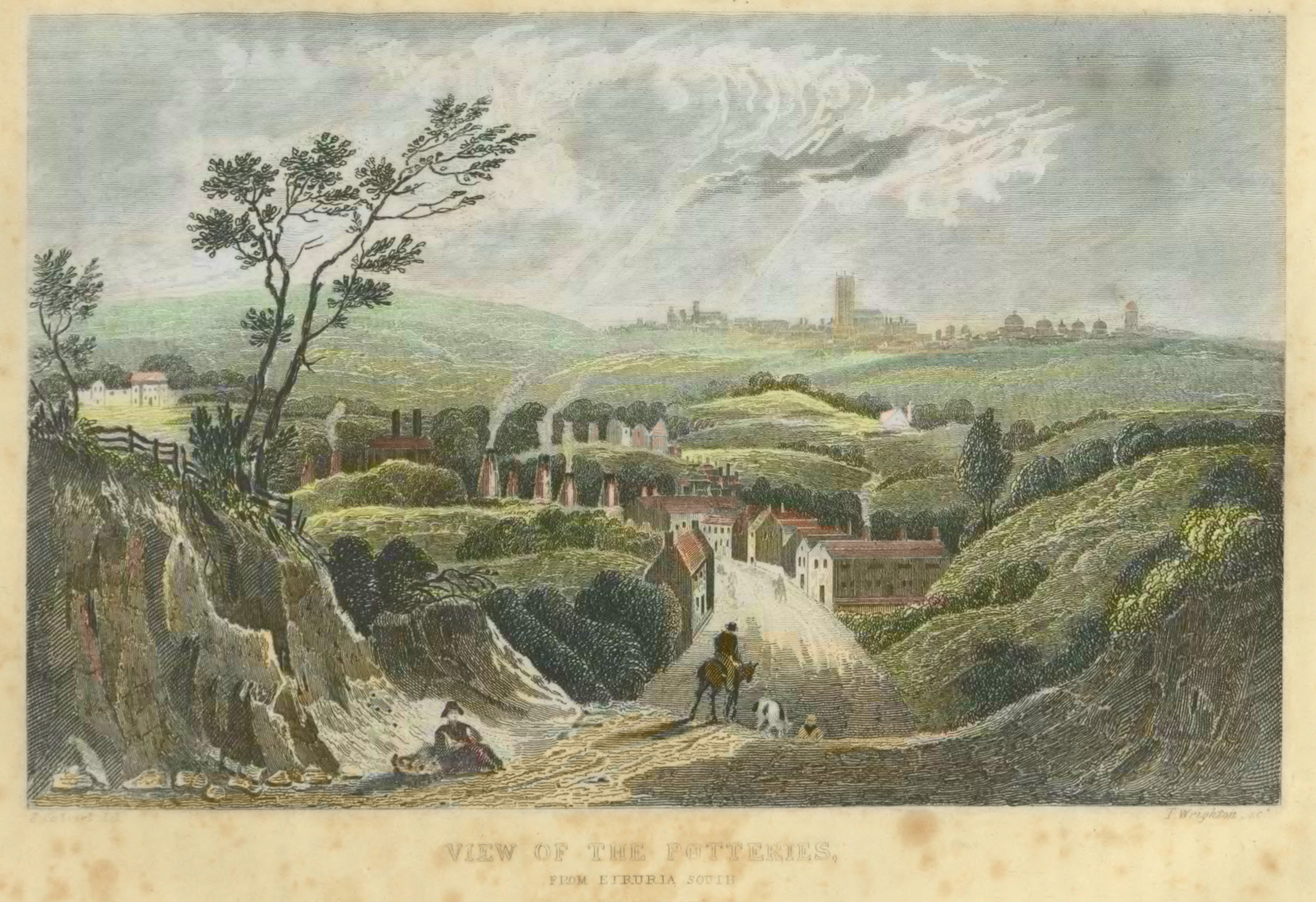

North Staffordshire’s local moor-monster Jenny Green-teeth, said to be resident under Doxey Pool in the Staffordshire Moorlands in modern times, is not recorded in the historical books and articles on Staffordshire folklore. Yet one does find the name attested in Victorian books and earlier sources, and as close as South Cheshire — where her kind presumably haunted the abundant meres and pool-strung “mosses”. There was also a late mermaid tale from Black Mere near Leek.

Doxey Pool, high in the Moorlands.

Doxey Pool, high in the Moorlands.

A detailed article by Charles P. G. Scott, “The Devil and His Imps”, is found in Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 1895, and this usefully and precisely surveys the evidence for a wealth of such old names in the British Isles. Scott remarks…

Jenny Green-teeth, in the vernacular Jinny Green-teeth, is the pretty name of a female goblin who inhabits wells or ponds. […] She is one of the very few female goblins [that are, in character] as frightful as male goblins” [since she was believed to bite and then drag children under the water].

In name she appears to be closely related to faintly glowing will-o-the-wisps, meaning the tricksy-lights especially likely to be seen above or encountered near marshy moorland pools or on gas-seeping rocky crags…

“Jenny with the lantern, Kitty with the wisp, and Joan in the wad [an East Cornwall ‘pisky’ name, a wandering light], are indeed mischievous damsels, but they are fair to look upon, and have no voracity.”

The furtherest back in time one can easily find the name in print is in the book A Glossary of the Words and Phrases of Furness (North Lancashire) (1869)…

Jinny-green-Teeth — green converva on pools.

Conversa here meaning…

“green scum on ponds, but supposed to imply the presence of a water-sprite or “boggart”, a terror to children as they pass the pond on which the appearance is seen.”

The Scott article (1895, see link above) also references the name of ‘Nelly Long-arms’, a very similar water-dweller to Jinny but instead to be found in deep wells. Nelly might draw children over the brink of the well. Presumably, the surface of a deep well being invisible down in the darkness, no child would be able to see the green weed which they deemed to indicate the presence of Jinny. Hence the need for another name, “Long-arms”.

There is no other indication, other than teeth and arms, of the actual physical appearance of Jenny Green-teeth. The absence of visual description being infinitely more scary to the child-mind than otherwise, since it calls the imagination into play. She is always solo and wholly supernatural. Meaning that there was no indication in the folklore that she was thought of as being akin to a medieval human witch, or was thought to have once been a witch but had since become a ghost. ‘Mermaids in pools’ do occasionally have tales that they were once accused as witches and drowned (e.g. Black Mere near Leek), but these are very late in time and were obviously confabulated on top of existing lore.

The lack of visual description hasn’t stopped modern confabulators from dreaming up and depicting all sorts of visual appearances for Jinny, from a fearsome mermaid to an eerie water-fairy to a green-skinned river-hag — though it is clear that she was never originally associated with rivers, only with isolated freshwater pools, wells, flooded quarry pools and Potteries marl-holes.

River spirits of the north obviously once had different names, recorded as ‘Peg Powler’ on the Tees, and ‘Peg-o’-Nell’ on the Ribble. These Pegs are the only two examples known, and as such my guess is that it’s possible they were Viking imports. Also suspect is the 1912 claim of a ‘river mermaid’ at Marden in Herefordshire (south West Midlands) which can be discounted as an obvious late invention, albeit confabulated on top of genuine lore about a lost church bell: “There is a tradition at Marden that there lies in the river Lugg [Herefordshire, former Mercia], near the church, a large silver bell, which will never be taken out until a team of white [female] oxen are thereto attached to draw it from the river.” Horses would not move it. This was reported in Archaeologia Cambrensis shortly after an “ancient [four-sided] bronze bell was actually discovered in a pond at Marden” in 1848, corroded and well below the sediment of centuries. Mrs E. M. Leather’s Folk-Lore of Herefordshire (1912) added to this a locally-heard tale that had grown up since 1848 of the “Mermaid of Marden”, deemed to have charge of the bell in the river, and which makes the two oxen into twelve. This obviously evolved locally from the 1848 bell discovery, and probably also via a reading of Hans Christian Andersen’s Danish story of “The Bell-Deep” on ‘the River-man and his bell’. But the initial story of the bell in the river seems interesting in relation to a wider related folkloric tradition of ‘stuck things’, the obvious antiquity of the river name of Lugg, and the more practical and better-attested historical practice of Irish monks who “concealed their bells by letting them down into the river” during times of war and attack.

Locally, the late books Folk-speech of South Cheshire (1887) and A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Chester (1886) also record the name Jinny Green-Teeth, both using much the same phrasing…

“Children are often deterred from approaching such places [as wells or ponds] by the threat that “Jinny Green-Teeth will have them.”

The name and tradition was also well attested in child-life around Warrington and Manchester, discussed in February 1870 in Notes and Queries. In this article there is a memory of the tradition extending up to some pits near Fairfield, Buxton, “Some half century ago”. Meaning, in the 1820s. A later note in a March issue of Notes and Queries adds that the common duckweed on ponds was then still known in Birmingham as ‘Jenny Greenteeth’, though the informant doesn’t state if this was still being personified in child-lore or if (in the urban environment) it had dwindled to just being a folksy plant name.

There is an interesting early partial example of the name, found on page 56 of Thomas Sternberg’s The Dialect And Folk-Lore Of Northamptonshire (1851), which usefully delves for a source for the name…

JINNY-BUNTAIL, s. The ignis fatuus, or Will with the wisp. Believed in Northamptonshire to proceed from a dwarfish spirit, who takes delight in misleading “night-faring clowns,” not unfrequently winding up a long series of torments by dragging victims into a river or pond. The word is evidently a corruption of Jinn with the burnt tail, Jild burnt tail.

“Will with the wisp, or Gyl burnt taylte.” – Gayton’s Notes on Don Quixote. London 1654. p. 97.

“An ignis fatuus, or exalation, and gillon a burnt tayle, or Will with the wispe.” Ibid, p. 268.

Here we glimpse how the Will o’ the wisp and Jenny Green-teeth may once have been deemed one and the same. Initially alluring and teasing, only to turn monstrous and fatal.

The book Lancashire folk-lore (1867) records one curious instance of a “Grindylow”, a name suspiciously similar to Beowulf‘s Grendel’s mother and unknown elsewhere…

“Aqueous nymphs or nixies, yclept “Grindylow,” and “Jenny Green Teeth,” lurked at the bottom of pits, and with their long, sinewy arms dragged in and drowned children who ventured too near.”

I suspect here that a wily local antiquarian was trying to claim for Lancashire the similar and rather more famous moorland female mere-monster of Grendel’s mother, found in Beowulf (1826 in English translation). By Nixies he refers to the Germanic ‘nixies’ and Icelandic ‘nykr’ (possibly Beowulf’s nicors and akin to the Germanic Moorjungfern), thus perhaps further indicating the antiquarian’s confabulating intentions. On the other hand, we do know that the six surviving lines of the lost Wade epic mention ‘nixies’ and water, which may suggest an English aspect.

But evidently some Jild– or Gyl– or Gill– word was once in fairly widespread use to mean a Will o’ the wisp, and this was closely associated with some slightly harder Jinn– or Ginn– name for a dangerous spirit who lurked below the surface of wells or ponds. As such, there may indeed be some link with the name of the Anglo-Saxon Grendel mother-monster. The Will o’ the wisp aspect (see Jinny-Buntail, above) indicates the ability to emerge from the pool and roam around, as Grendel’s mother does in Beowulf. Note that in Beowulf, at the haunted mere in the story a… “dreadful wonder does appear each night, a fire on the flood”, which perhaps indicated a glowing will o’ the wisp. “Flood” implies ‘wide and still’, a mirror-like surface.

Possibly there is some folk memory of this overall tradition in the famous and enduring nursery-rhyme “Jack and Jill went up the hill / to fetch a pail of water / Jack fell down / And broke his crown / And Jill came tumbling after”. This associates the Gill- name with a well, water, and with falling and tumbling (“fell down” the well, rather than the hill?), and resulting child-injury. Shakespeare may have played upon his audience’s everyday knowledge of such a rhyme in his famous A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where he gives the line: “Jack shall have Jill; Nought shall go ill”.

The “crown” here is of course a part of the head, and if Jack and Jill “fell down” the well rather than than hill, then there would be a certain level of ritual resonance at play in the rhyme. For instance, David Rudling in Ritual Landscapes of Roman South East Britain (2008) remarks on a very ancient British cultic tradition that once linked wells with heads…

“… a pre-Roman cult of the head, an ancient custom dating back to the late Bronze Age, which continued long into the Roman period (ibid, 96-97). As well as skulls deposited in streams, a human skull was found deposited after a well in Queen Street had silted up (GM 1 44). There are numerous accounts of other finds of skulls, both human and animal, in Romano-British wells and their magical power is recorded in many Celtic legends (Merrifield 1969, 176).”

The archaeologists are more cautious on that…

“Certain Celtic ritual activity, such as deposition of ‘head objects’ re-emerged strongly in the fourth century in Roman Britain. Although Ross refers to this as a ‘cult’ of the head, it is probably best described as part of a general phenomenon, and not a ‘cult’ (Riddel 1990).” (Theoretical Roman Archaeology: Conference Proceedings, 1993, page 123).

But even a cautious appraisal of this ancient phenomenon suggests a possible linkage with the famous nursery rhyme. Could a Gill have been a name for the annual sacrificial child-victim, rather than the deity of the water? But perhaps it just relates to being ‘in service to the water’ — consider for instance that in the British Isles (north of about the Wye), “a gilly” is an estate’s river servant, an experienced man of quality who knows rivers, fishing and pools. One who accompanies the estate’s master and guests on fishing trips.

Evidently, there is some nexus of ancient belief at play among these surviving words and fragments, though while we can just about glimpse its outlines we may never know for sure quite what it was.

What can be noted in closing is that as ‘a frightening figure that threatens drowning’ she has a close similarity in modus operandi with aspects of the widespread Northern folk idea of the strong and male water-horse connected with rivers. This supernatural shape-changing river-spirit will emerge from a river to stand stock still and thus tempt people to mount and try to ride him. Immediately they do so he will race away back to the river with wind-like speed and plunge in, drowning the rider. There is an obvious and close parallel here between the still pool and still river-horse, and the temptation to the unwary and the drowning are both the same. Dag Stromback has a fine and detailed overview discussion of… “the old and fundamental idea” of the water-horse “within the Nordic area … and their similarity with Scottish, Irish and Breton traditions” in his essay “Some Notes on the Nix in the Older Nordic Tradition”, in Mandel and Rosenberg, Medieval literature and folklore studies: essays in honor of Francis Lee Utley, Rutgers University Press, 1970.

Interestingly, in relation to my recent delvings here on the overlap between insects and pisky (once deemed the souls of dead children), Jinny is found in “A Glossary of the Words and Phrases of Furness (North Lancashire)” (1869), which offers…

Jinny-spinner — an insect (Tipula).

Tipula is the class of insects that include Daddy Long-legs and Crane-flies, but A Glossary of North Country Words (1825) suggests the country folk understood a broader class of any “very long slenderlegged” fly. Which implies that the presence of pond-skaters on the surface of a still freshwater pool could also be taken by northern children to be a similar ‘danger indicator’ of the presence of Jinny under the water, akin to the ‘green teeth’ pond-weed. Interestingly the name in Scotland was Jenny Nettles, the Scots word for long slenderlegged insects. Nettles arising from Scotland’s notorious profusion of biting long-legged midges, which presumably caused a nettle-like rash.

Also in the north, The Dialect of Craven in the West-Riding of the Country of York (1828) records…

JINNY SPINNER, A large fly, called also ‘Harry long legs’. “Her wagon spokes made of long spinners legs.” Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet.

This latter quote is from Shakespeare’s description of Queen Mab…

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate-stone

On the fore-finger of an alderman

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Athwart men’s noses as they lie asleep

Her wagon-spokes made of long spinners’ legs

The cover of the wings of grasshoppers

The traces of the smallest spider’s web …

Evidently then “spinners” — and presumably also the common name Jinny-spinners — was known to a South Warwickshire playwright and was deemed to be easily understood by a London audience of play-goers in the 1590s.

Incidentally I also found in A Glossary of North Country Words, in Use (1829)…

“‘By Jinkers’, a sort of demi-oath. From jingo.”

Again, this points to a Jinn– or Ginn– name which was perhaps once some sort of spirit which could be invoked by a veiled oath. One wonders if jingo was where Tolkien got the original name for Frodo, who was for a short while to have been called ‘Bingo’ in an early draft. Possibly not, as family members reportedly later remembered that Tolkien probably… “derived his name from the Bingos, a family of toy koala bears owned by the Tolkien children”. But the definitive Tolkien Companion seems unsure on this, and remarks “perhaps” on this claim.

The word Jinkers / Jingo is uncertain but has been variously suggested to be: the Roman god Jove; early stage conjurers’ language akin to “Hey presto!”; a veiled oath which was Puritan slang for the obscure Saint Gengulphus or Gingolph (so obscure he presumably wouldn’t be offended by the oath); or an actual euphemism for Jesus or God (in Basque, Jinko is God).

“Bingo” was also recorded prior to the popularity of the game of bingo (newly popular under that new name in the 1920s) as being “A customs officers’ term, the triumphal cry being employed on a successful search” for contraband. Possibly this use was a contraction of “By jingo!” to “b’ingo”, the old word jingo having by then been made unavailable — due to its having accidentally taken on the new connotation of ‘jingoistic’ or ‘displaying a proudly militaristic nationalism’.