“Many folk beliefs went beyond merely avoiding the rainbow’s spiritual power [a rainbow was believed to harm anyone who pointed to it] — they try to manipulate it. […] Children in Staffordshire, England, attempted to [break the power of rainbows to harm a pointing person] by crossing a pair of sticks or straws on the ground and placing a stone or two atop them, the goal being literally to cross out [the power of] any rainbow they saw.”

— from: Raymond L. Lee, Jr. and Alistair B. Fraser. The Rainbow Bridge: rainbows in art, myth, and science. Penn State University Press and SPIE Optical Engineering Press, 2001.

Author Archives: David Haden

Mirrors and souls

My answer to a question Blood and Bone China asked on Facebook…

Q: Where does the myth about not being able to see a vampire’s reflection in a mirror come from?

A: The vampire is deemed not to have a soul, and hence no mirror will reflect him or her. The idea probably came originally from the prehistoric association of pools with sacred deities that were deemed to inhabit them, a widespread belief testified to by abundant votive offerings found by archaeologists at the bottom of ancient pools and ponds in the UK and Europe. Reflections seen in such places were thought to be reflections of the soul, not of the actual body, and hence to pose a danger of seduction. This could be either a danger of self-love (seen in the myth of Narcissus, etc), or a danger of the person’s soul being “taken under” by the watery deity. Possibly this had a root in a belief that one had to shed one’s selfishness when approaching such places, or risk calamity. Then, when mirrors came along in the Bronze Age, these would have been seen as having the similar capability to ‘steal’ or “embody” one’s soul, in much the same way as the similarly reflective dark watery pool. Modern tribal peoples often have similar beliefs, even today, about mirrors and camera lenses and their potential to “steal” one’s soul. As David Jones says, there are also several mirror folk beliefs around funerals and souls (i.e.: cover mirrors while laying out the dead body in a home) that have persisted to the modern day in certain places. The folk association of “bad luck” with breaking household mirrors probably also dates back to such antiquated beliefs. All these can be traced to the idea that the reflection in a mirror is that of the soul, not of the body.

19th century Buxton Mermaid investigated by scientists…

The mid 19th century “Buxton Mermaid” doll is being investigated by scientists…

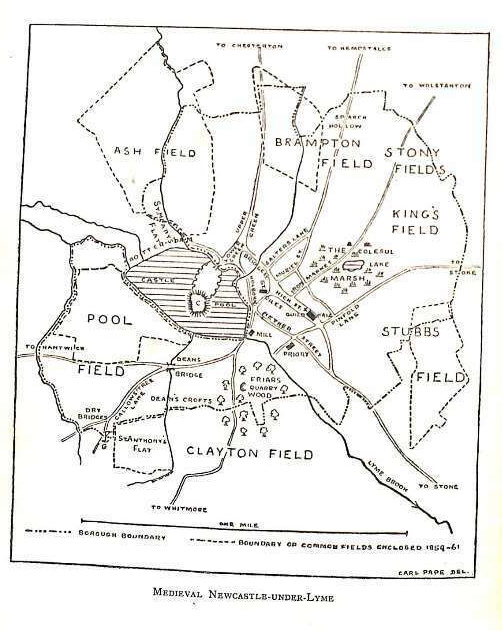

Staffordshire in the early 1600s

Staffordshire, as seen in the volume ‘England Wales Scotland and Ireland Described and Abridged with ye Historic Relation of things Worthy memory from a farr larger Voulume Done by John Speed. Anno Cum privilegio 1620’…

[ Thanks to: SeriyKotik1970, who has a larger version ]

Apparently they were engraved in the early years of the 1600s, and also appeared in Camden’s Britannia in 1617.

Update, April 2018: huge version, non tatty…

* Old road expert, Charles G. Harper, in his The Manchester and Glasgow road Vol. 1 (1907), on the oldest post-road from Manchester to London in the district…

To go back to still earlier times [17th century, one saw only] horsemen, who were then your only travellers, jogging along from Manchester to London by way of the roundabout route of Warrington, Great Budworth, Cranage Heath, Holmes Chapel, Brereton, Church Lawton, [Red Street,] Newcastle-under-Lyme, whence they would generally proceed by Stone, Lichfield, and Coleshill. That was, with minor divagations suggested by taste and fancy, or by such circumstances as floods or highwaymen, the old original post-road.

Interestingly, Red Street to Holmes Chapel was later my suggestion for the likely route of Sir Gawain’s entry into North Staffordshire in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

The Etruria Valley landscape in the mid 1860s

This was the sort of landscape you had in Stoke-on-Trent in the mid 1860s. This is a large oil painting by Henry Lark Pratt (1805-1873), “Etruria from Basford Bank”. Shelton Church can be seen in the distance over in the far right of the picture, Etruria Hall is on the left. This is the landscape through which the hero of the novel The Spyders of Burslem travels on the train from Stoke station to Longport station.

“I glimpsed [from the steam train] old women and girls out collecting sloeberries along the thick hedges of the rail line. I was obviously in one of those industrial districts where the countryside ways and the new manufacturing ways lived strangely side-by-side. It seemed a bucolic and rustic glimpse, but I had no doubt that each of those rosy-cheeked girls had a tongue in her head that would clip a hedge.” — from The Spyders of Burslem

It’s slightly cropped at the top and bottom, as can be seen from this thumbnail…

The new Basford Bank road was built 1828, alongside the older and much steeper Fowlea Bank road (seen here as the roofs paralleling the new road) which is the logical place at which the old Roman road at Wolstanton could have dropped down the side of the valley to reach what is now the Stoke station area (where it’s known to have run). Further down the valley was too likely to be flooded out in winter where the Fowlea met the Trent.

Staffordshire University lecture on the 1860s

Staffordshire University is to host a public lecture on the ‘Potteries, Public Health and Karl Marx’. Specifically Das Kapital, in which Karl Marx selected a paragraph of evidence from an appendix of the voluminous Royal Commission on Employment of Children (1862, published 1863), to illustrate the conditions of the Potteries workers in the early 1860s…

From the report of the Commissioners [published] in 1863, the following: Dr. J.T. Arlidge, senior physician of the North Staffordshire Infirmary, says: “The potters as a class, both men and women, represent a degenerated population, both physically and morally. They are, as a rule, stunted in growth, ill-shaped, and frequently ill-formed in the chest; they become prematurely old, and are certainly short-lived …”

Actually, Marx slightly mis-quoted Arlidge, and also mis-spelled his name as “Arledge”. But what is interesting, and what Marx neglects to mention, is that Arlidge had literally only just arrived in the district when Assistant Commissioner Longe of the 1862 Commission was taking evidence in the Potteries in April 1862, and that Arlidge had then undertaken no systematic research in Stoke. His main academic training in London had been in Botany. He had moved up from Kent to Newcastle-under-Lyme in 1862, and although he had once been apprenticed to a GP, in Kent he had been wholly a psychiatrist (then called an ‘alienist’) — only interested in the treatment of the mentally ill. In the Potteries he kept rooms at Trentham and a house at Newcastle-under-Lyme, so he was not exactly cheek-by-jowl with the workers. His comments were regarded as extreme, at the time, by people in the Potteries and by medical colleagues, and he had to defend them in the letters pages of the Staffordshire Sentinel. Basically his reply seems to have been that the notion was ‘common knowledge’. Yet one of his colleagues, William Spanton of the North Staffordshire Infirmary, later wrote in his 1920 memoirs that Arlidge had… “greatly offended manufacturers and his medical associates” with his comments.

As it was, Arlidge was broadly correct on the statistical fact of pottery workers as a class being “short-lived”, although this appears to have been concentrated among particular types of pottery workers. After the firing process, some of the dry and finely-powdered flint adheres to the ceramic ware. This has to be removed by hand scouring. Fragments of the fine dry flint dust (flint was ground up with bone to make the wet ‘slip’ for the clay) can be inhaled by a type of worker called ‘scourers’, and presumably also by those unpacking and sweeping the kilns, and this gave rise to lung diseases. This, together with exposure to lead in some decorating paints, had by the early 1860s led to an overall higher death rate in potteries workers than in other large industries. Arlidge noted scourers were “always women belonging usually to the rougher, more ignorant and reckless of their sex”. Many manufacturers rapidly shifted to leadless or reduced-lead glazes, but the flint dust was generally only dealt with by forced ventilation during the scouring process.

On the overall death-rate, Arlidge was in 1864 able to produce new research, distributed by him in a pamphlet rather than a medical journal, proving his earlier anecdotal claim that potters were “short-lived”. Yet it seems that his wider comments — those used by Marx and forever thereafter repeated as gospel by socialists — were highly contested by other local medical men and by the local people at the time, and were not then based on any research work done by Arlidge himself or even on his general training of treating physical ailments in an industrial environment. Arlidge did later write a book on the subject of industrial diseases, but his findings have been found wanting. For instance, a 1973 scholarly article in the Journal of Industrial Medicine by E. Posner concluded that: “it must be recorded that many passages in Arlidge’s book [on industrial health] have not withstood the test of time”.

Conditions were indeed bad in certain types of small workshops of the mid 1800s, especially for the young children who would often be sent to work by alcoholic adults ‘in the place’ of the adult. But the quotes selected by Marx have the effect of giving the impression that the problems swept across the whole of the industry, and indeed the whole population of the district, rather than being largely confined to certain specific tasks within ceramics production. Marx’s slight mis-quoting of Arlidge serves to emphasize this effect on the reader.

Marx also neglects to mention that a Dr. Boothroyd — whom he selectively quotes as saying that: “Each successive generation of potters is more dwarfed and less robust than the preceding one” — was also the mayor of Hanley, and thus presumably a highly political figure. One suspects it was from Boothroyd and his circle that Arlidge adopted his initial prejudiced position on Potteries health. In 1878 Arlidge was himself elected Mayor of Newcastle-under-Lyme, a little more than ten years after arriving in the district. Thus one has to wonder what part headline-grabbing claims about health problems played in the local politics of the day.

Emily & Jen Dance for Deeron

Another new and local novel, just discovered. Emily & Jen Dance for Deeron is a novel based around the ancient Abbots Bromley Horn Dance. Said to…”blend folklore, fantasy, dance and music into a magical adventure of good versus evil and enduring friendship”. The author is planning a related “high quality film that will feature on many media platforms”.

Brickhouse / Cock Yard, Burslem

Maddock in 3D

Scott Spencer gets quite close to how I imagined the face of Maddock the faun, in my novel The Spyders of Burslem. It’s a virtual 3D sculpture…

Waerburg and the geese

Another bit of memorable local folklore that caught my eye…

From: Abbie Farwell Brown, The Book of Saints and Friendly Beasts (Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1900).

SAINT WERBURGH & HER GOOSE

I.

SAINT WERBURGH was a King’s daughter, a real princess, and very beautiful. But unlike most princesses of the fairy tales, she cared nothing at all about princes or pretty clothes or jewels, or about having a good time. Her only longing was to do good and to make other people happy, and to grow good and wise herself, so that she could do this all the better. So she studied and studied, worked and worked; and she became a holy woman, an Abbess. And while she was still very young and beautiful, she was given charge of a whole convent of nuns and school-girls not much younger than herself, because she was so much wiser and better than any one else in all the countryside.

But though Saint Waerburg had grown so famous and so powerful, she still remained a simple, sweet girl. All the country people loved her, for she was always eager to help them, to cure the little sick children and to advise their fathers and mothers. She never failed to answer the questions which puzzled them, and so she set their poor troubled minds at ease. She was so wise that she knew how to make people do what she knew to be right, even when they wanted to do wrong. And not only human folk but animals felt the power of this young Saint. For she loved and was kind to them also. She studied about them and grew to know their queer habits and their animal way of thinking. And she learned their language, too. Now when one loves a little creature very much and understands it well, one can almost always make it do what one wishes— that is, if one wishes right.

For some time Saint Werburgh had been interested in a flock of wild geese which came every day to get their breakfast in the convent meadow, and to have a morning bath in the pond beneath the window of her cell. She grew to watch until the big, long-necked gray things with their short tails and clumsy feet settled with a harsh “Honk!” in the grass. Then she loved to see the big ones waddle clumsily about in search of dainties for the children, while the babies stood still, flapping their wings and crying greedily till they were fed.

There was one goose which was her favorite. He was the biggest of them all, fat and happy looking. He was the leader and formed the point of the V in which a flock of wild geese always flies. He was the first to alight in the meadow, and it was he who chose the spot for their breakfast. Saint Werburgh named him Grayking, and she grew very fond of him, although they had never spoken to one another.

Master Hugh was the convent Steward, a big, surly fellow who did not love birds nor animals except when they were served up for him to eat. Hugh also had seen the geese in the meadow. But, instead of thinking how nice and funny they were, and how amusing it was to watch them eat the worms and flop about in the water, he thought only, “What a fine goose pie they would make!” And especially he looked at Grayking, the plumpest and most tempting of them all, and smacked his lips. “Oh, how I wish I had you in my frying-pan!” he said to himself.

Now it happened that worms were rather scarce in the convent meadow that spring. It had been dry, and the worms had crawled away to moister places. So Grayking and his followers found it hard to get breakfast enough. One morning, Saint Werburgh looked in vain for them in the usual spot. At first she was only surprised; but as she waited and waited, and still they did not come, she began to feel much alarmed.

Just as she was going down to her own dinner, the Steward, Hugh, appeared before her cap in hand and bowing low. His fat face was puffed and red with hurrying up the convent hill, and he looked angry.

“What is it, Master Hugh?” asked Saint Werburgh in her gentle voice. “Have you not money enough to buy to-morrow’s breakfast?” for it was his duty to pay the convent bills.

“Nay, Lady Abbess,” he answered gruffly; “it is not lack of money that troubles me. It is abundance of geese.”

“Geese! How? Why?” exclaimed Saint Werburgh, startled. “What of geese, Master Hugh?”

“This of geese, Lady Abbess,” he replied. “A flock of long-necked thieves have been in my new- planted field of corn, and have stolen all that was to make my harvest.” Saint Werburgh bit her lips.

“What geese were they?” she faltered, though she guessed the truth.

“Whence the rascals come, I know not,” he answered, “but this I know. They are the same which gather every morning in the meadow yonder. I spied the leader, a fat, fine thief with a black ring about his neck. It should be a noose, indeed, for hanging. I would have them punished, Lady Abbess.”

“They shall be punished, Master Hugh,” said Saint Werburgh firmly, and she went sadly up the stair to her cell without tasting so much as a bit of bread for her dinner. For she was sorry to find her friends such naughty birds, and she did not want to punish them, especially Grayking. But she knew that she must do her duty.

When she had put on her cloak and hood she went out into the courtyard behind the convent where there were pens for keeping doves and chickens and little pigs. And standing beside the largest of these pens Saint Werburgh made a strange cry, like the voice of the geese themselves,—a cry which seemed to say, “Come here, Grayking’s geese, with Grayking at the head!” And as she stood there waiting, the sky grew black above her head with the shadowing of wings, and the honking of the geese grew louder and nearer till they circled and lighted in a flock at her feet.

She saw that they looked very plump and well-fed, and Grayking was the fattest of the flock. All she did was to look at them steadily and reproachfully; but they came waddling bashfully up to her and stood in a line before her with drooping heads. It seemed as if something made them stay and listen to what she had to say, although they would much rather fly away.

Then she talked to them gently and told them how bad they were to steal corn and spoil the harvest. And as she talked they grew to love her tender voice, even though it scolded them. She cried bitterly as she took each one by the wings and shook him for his sins and whipped him—not too severely. Tears stood in the round eyes of the geese also, not because she hurt them, for she had hardly ruffled their thick feathers; but because they were sorry to have pained the beautiful Saint. For they saw that she loved them, and the more she punished them the better they loved her. Last of all she punished Grayking. But when she had finished she took him up in her arms and kissed him before putting him in the pen with the other geese, where she meant to keep them in prison for a day and a night. Then Grayking hung his head, and in his heart he promised that neither he nor his followers should ever again steal anything, no matter how hungry they were. Now Saint Werburgh read the thought in his heart and was glad, and she smiled as she turned away. She was sorry to keep them in the cage, but she hoped it might do them good. And she said to herself, “They shall have at least one good breakfast of convent porridge before they go.”

Saint Werburgh trusted Hugh, the Steward, for she did not yet know the wickedness of his heart. So she told him how she had[60] punished the geese for robbing him, and how she was sure they would never do so any more. Then she bade him see that they had a breakfast of convent porridge the next morning; and after that they should be set free to go where they chose.

Hugh was not satisfied. He thought the geese had not been punished enough. And he went away grumbling, but not daring to say anything cross to the Lady Abbess who was the King’s daughter.

II.

SAINT WERBURGH was busy all the rest of that day and early the next morning too, so she could not get out again to see the prisoned geese. But when she went to her cell for the morning rest after her work was done, she sat down by the window and looked out smilingly, thinking to see her friend Grayking and the others taking their bath in the meadow. But there were no geese to be seen! Werburgh’s face grew grave. And even as she sat there wondering what had happened, she heard a prodigious[61] honking overhead, and a flock of geese came straggling down, not in the usual trim V, but all unevenly and without a leader. Grayking was gone! They fluttered about crying and asking advice of one another, till they heard Saint Werburgh’s voice calling them anxiously. Then with a cry of joy they flew straight up to her window and began talking all together, trying to tell her what had happened.

“Grayking is gone!” they said. “Grayking is stolen by the wicked Steward. Grayking was taken away when we were set free, and we shall never see him again. What shall we do, dear lady, without our leader?”

Saint Werburgh was horrified to think that her dear Grayking might be in danger. Oh, how that wicked Steward had deceived her! She began to feel angry. Then she turned to the birds: “Dear geese,” she said earnestly, “you have promised me never to steal again, have you not?” and they all honked “Yes!” “Then I will go and question the Steward,” she continued, “and if he is guilty I will punish him and make him bring Grayking back to you.”

The geese flew away feeling somewhat comforted, and Saint Werburgh sent speedily for Master Hugh. He came, looking much surprised, for he could not imagine what she wanted of him. “Where is the gray goose with the black ring about his neck?” began Saint Werburgh without any preface, looking at him keenly. He stammered and grew confused. “I—I don’t know, Lady Abbess,” he faltered. He had not guessed that she cared especially about the geese.

“Nay, you know well,” said Saint Werburgh, “for I bade you feed them and set them free this morning. But one is gone.”

“A fox must have stolen it,” said he guiltily.

“Ay, a fox with black hair and a red, fat face,” quoth Saint Werburgh sternly. “Do not tell me lies. You have taken him, Master Hugh. I can read it in your heart.” Then he grew weak and confessed.

“Ay, I have taken the great gray goose,” he said faintly. “Was it so very wrong?”

“He was a friend of mine and I love him dearly,” said Saint Werburgh. At these words the Steward turned very pale indeed.

“I did not know,” he gasped.

“Go and bring him to me, then,” commanded the Saint, and pointed to the door. Master Hugh slunk out looking very sick and miserable and horribly frightened. For the truth was that he had been tempted by Grayking’s fatness. He had carried the goose home and made him into a hot, juicy pie which he had eaten for that very morning’s breakfast. So how could he bring the bird back to Saint Werburgh, no matter how sternly she commanded?

All day long he hid in the woods, not daring to let himself be seen by any one. For Saint Werburgh was a King’s daughter; and if the King should learn what he had done to the pet of the Lady Abbess, he might have Hugh himself punished by being baked into a pie for the King’s hounds to eat.

But at night he could bear it no longer. He heard the voice of Saint Werburgh calling his name very softly from the convent, “Master Hugh, Master Hugh, come, bring me my goose!” And just as the geese could not help coming when she called them, so he felt that he must go, whether he would or no. He went into his pantry and took down the remains of the great pie. He gathered up the bones of poor Grayking in a little basket, and with chattering teeth and shaking limbs stole up to the convent and knocked at the wicket gate.

Saint Werburgh was waiting for him. “I knew you would come,” she said. “Have you brought my goose?” Then silently and with trembling hands he took out the bones one by one and laid them on the ground before Saint Werburgh. So he stood with bowed head and knocking knees waiting to hear her pronounce his punishment.

“Oh, you wicked man!” she said sadly. “You have killed my beautiful Grayking, who never did harm to any one except to steal a little corn.”

“I did not know you loved him, Lady,” faltered the man in self-defense.

“You ought to have known it,” she returned; “you ought to have loved him yourself.”

“I did, Lady Abbess,” confessed the man. “That was the trouble. I loved him too well—in a pie.”

“Oh, selfish, gluttonous man!” she exclaimed in disgust. “Can you not see the beauty of a dear little live creature till it is dead and fit only for your table? I shall have you taught better. Henceforth you shall be made to study the lives and ways of all things which live about the convent; and never again, for punishment, shall you eat flesh of any bird or beast. We will see if you cannot be taught to love them when they have ceased to mean Pie. Moreover, you shall be confined for two days and two nights in the pen where I kept the geese. And porridge shall be your only food the while. Go, Master Hugh.”

So the wicked Steward was punished. But he learned his lesson; and after a little while he grew to love the birds almost as well as Saint Werburgh herself.

But she had not yet finished with Grayking. After Master Hugh had gone she bent over the pitiful little pile of bones which was all that was left of that unlucky pie. A tear fell upon them from her beautiful eyes; and kneeling down she touched them with her white fingers, speaking softly the name of the bird whom she had loved.

“Grayking, arise,” she said. And hardly had the words left her mouth when a strange thing happened. The bones stirred, lifted themselves, and in a moment a glad “Honk!” sounded in the air, and Grayking himself, black ring and all, stood ruffling his feathers before her. She clasped him in her arms and kissed him again and again. Then calling the rest of the flock by her strange power, she showed them their lost leader restored as good as new.

What a happy flock of geese flew honking away in an even V, with the handsomest, grayest, plumpest goose in all the world at their head! And what an exciting story he had to tell his mates! Surely, no other goose ever lived who could tell how it felt to be made into pie, to be eaten and to have his bones picked clean by a greedy Steward.

This is how Saint Werburgh made lifelong friendship with a flock of big gray geese. And I dare say even now in England one of their descendants may be found with a black ring around his neck, the handsomest, grayest, plumpest goose in all the world. And when he hears the name of Saint Werburgh, which has been handed down to him from grandfather to grandson for twelve hundred years, he will give an especially loud “Honk!” of praise.

My notes:

The above story originally appeared in the Acta Sanctorum, with a lost version in the Vita S. Amelberga. Also in Goscelin’s Life of St Waerburh. The name “greyking” (used above) seems to have been a Victorian confabulation.

William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Pontificum Anglorum (early 1100s) says of the location of the story that…

“Waerburg had land in the country beyond the walls of Chester whose crops were being preyed upon by wild geese. The bailiff in charge [unknown name] did all he could to drive them away, but with little success. So, one day, when he was in attendance on his mistress, he put in a complaint about the matter. ‘Go,’ she said, ‘and shut them all up indoors.’ When he realised she was not joking, he went back to the crops and laid down the law in a loud voice: they must follow him as his lady commanded. They formed a flock, lowered their necks, trooped after their foe, and were all penned up. The bailiff took the opportunity to have one of them for supper. At dawn came the virgin. She reproached the birds for stealing things that did not belong to them, and told them to be gone. But the birds, sensing that not all of them are present, refused to make move. God inspired her to realize that the birds were not making all this fuss for nothing, so she closely questioned the bailiff and discovered the theft. She told him to assemble the goose’s bones and bring them to her. At a healing gesture of her hand, skin and flesh immediately formed on the bones, and the skin began to sprout feathers; then the bird came to life and after a preliminary jump launched itself into the sky.”

Despite this Cheshire location, the story seems to have later been appropriated by the East Midlands, specifically by Weedon Bee where Waerburg was Abbess later in her life. There is quite a tedious history to be found in the tug-of-war around the “moving” of relics associated with her, and the moving of the site of the goose legend is perhaps a literary aspect of that. The tale has also been retold in modern times in the book Folk Tales of the East Midlands (1954).

The one misericord unique to Chester Cathedral choir-stalls is of this goose “Miracle of St Werburg” story.

Her goose imagery passed into medieval iconography, specially as a five-goose pilgrimage emblem…

“St Werburgh’s main emblem in medieval iconography was the goose. She is supposed to have restored five of these to life: David Hugh Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Oxford, 1987), 434; The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford, 1990), 273, 1466″ — from Alex Bruce, The Cathedral ‘open and free’: Dean Bennett of Chester. Liverpool University Press.

The goose emblem perhaps throws new light on the meaning of the now-lost stone carvings on the Minster at Stoke town (the Saxon ruins of which can still be seen in the grounds of the new Minster). We know — from inspections carried out shortly before demolition in 1826 — that the old Saxon stone church at Stoke had a large carved swan or goose above its south door, and some other web-footed bird above the north door. Sadly, the heavily eroded webbed feet were all that remained above the north door, by the time someone wrote about it (see: p.463 of The Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent by John Ward). The site of the church is at the meeting point of the young River Trent and the Fowlea, an obvious habitat for water-birds.

For more discussion of the local folklore of waterfowl, see my History of Burslem & the Fowlea Valley.

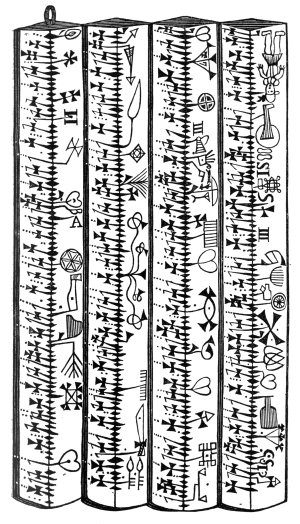

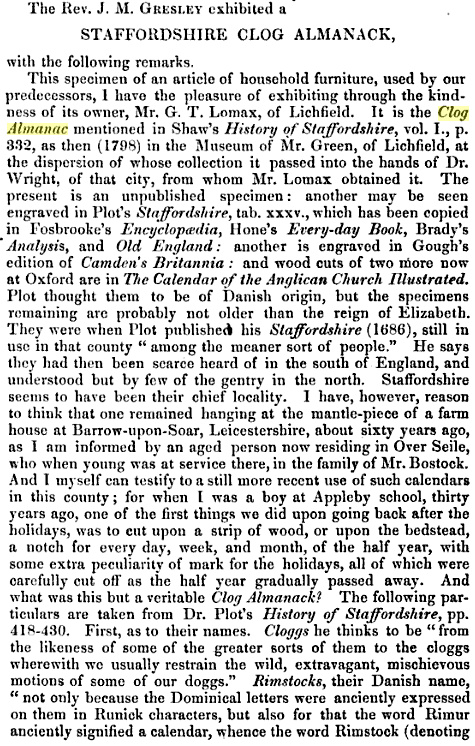

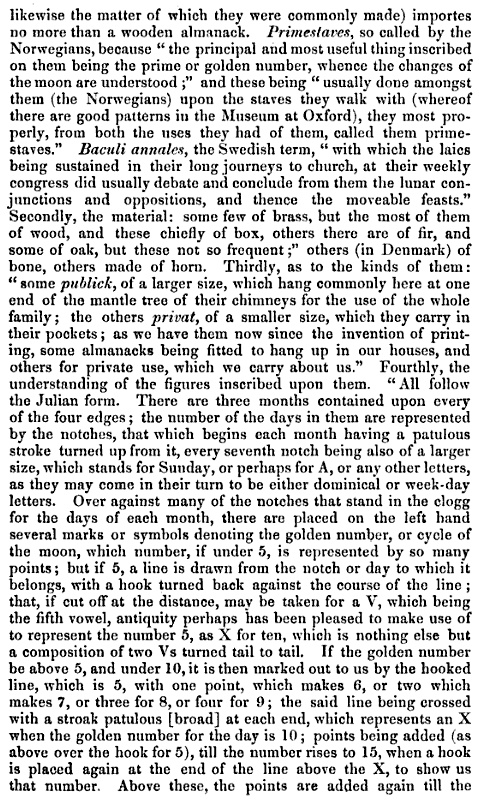

Staffordshire Clogg Almanacs

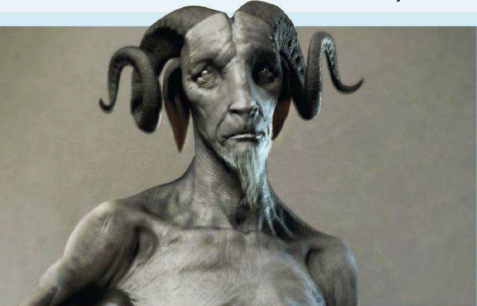

Notes on a Staffordshire Clogg Almanac:—

“Almanacs of a rude kind, known as clogg almanacs, consisting of square blocks of hard wood, about 8in. in length, with notches along the four angles corresponding to the [special] days of the year [in a perpetual calendar], were in use in some parts of England as late as the 17th century.” — Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1902.

They do not seem to appear in Cheshire or Shropshire or further south than the Trent. Raven’s book The Folklore of Staffordshire claims of these that…

“The Staffordshire Clogg Almanacs were in use at the time of the Saxon Conquest, and it is clear from the available evidence that the customs associated with the [special] day[s marked on it] are very old.”

Below is an engraving of a Staffordshire clogg almanac, formerly in the Lichfield Museum, drawn more graphically from a fine copy published in the Anastatic Drawing Society’s volume for 1860…

A full deciphering can be seen here.

This example was later described at length by the Rev. J. M. Gresley, in the Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archeological Society, Volume One, page 410…

There is also this useful later snippet from the 1899 Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society…

“Mr. W.T. Browne, the governor of Chetham Hospital, exhibited two clog almanacs belonging to the institution, on which Mr. Yates made the following remarks: The two interesting clog almanacs, which are on the table, are two good specimens, and exceedingly rare. One of them was presented to the Chetham Library by Mr. Henry Finch in 1696, and the other by Mr. John Moss in 1711. They have been fully described by Mr. John Harland in [“On Clog Almanacs, or Rune Stocks” in] the Reliquary vol. V., 1865. Dr. Robert Plot, in his Natural History of Staffordshire (folio, 1686), gives an account of the clog almanac, which he found in popular use in that and other northern counties, but unknown further south, and which, from its being also used in Denmark, he conceived to have come into England with our Danish invaders and settlers many centuries before. The clog bore the same relation to a printed almanac which the Exchequer tallies bore to a set of account books. Properly it was a perpetual almanac, designed mainly to show the Sundays and other fixed holidays of the year, each person being content, for use of the instrument, to observe on what day the year actually began, as compared with that represented on the clog; so that if they were various, a brief mental calculation of addition or subtraction was sufficient to enable him to attain what he desired to know. The entire series of days constituting the year was represented by notches running along the angles of the square block, each side and angle thus presenting three months. The first day of a month was marked by a notch having a patulous stroke turned up from it, and each Sunday was distinguished by a notch somewhat broader than usual. There were indications — but they are not easily described — for the golden number and the cycle of the moon. The feasts were denoted by symbols resembling hieroglyphics.

Dr. J. Barnard Davis, in an elaborate article on “[Some Account of] Runic Calendars and Staffordshire Clogg Almanacs” in Archaologia, vol. xli., part ii. (1867 [pp. 453-478]), enumerates sixteen specimens known to him, including one in his own possession purchased at the sale of Mr. Charles Bradbury’s collection in 1864, the “Finch Clog” and the “Moss Clog” in the Chetham Library, one in the possession of the Historic Society at Liverpool, and another belonging to the Rev. J. S. Doxey, Rochdale. A fine specimen, recently in the possession of Messrs. Sherratt and Hughes, booksellers, Manchester, is now in the collection of Mrs. Robinow, Fair Oak, West Didsbury.”

Here is a simpler Staffordshire clogg almanac, in the British Museum (AN885002001)…

A more recent paper on Staffordshire clog almanacs was the presidential address delivered at the eighty-third annual meeting of the North Staffordshire Field Club, March 26th, 1949. Reprinted in Transactions of the North Staffordshire Field Club, 1948-49. Sadly this is not online. A bundle of papers, cuttings, and letters relating to the lecture is held at the Salt Library in Stafford.

It seems highly unlikely that the Vikings brought the notion of such almanacs to Britain, as seems to have been the common notion idea among scholars in the middle of the 19th century. Why would pagans bring calendars that ran according to the Julian and Christian years? We sent Christianity to them, not visa versa. There was counter-evidence to the unproven “Vikings” theory. For instance, Eirikr Magnusson (1877) suggested that the Danish cloggs actually originated in England, pointing to a runic calendar found in Lapland in 1866 that bore English runes. (Cambridge Antiq. Soc. Communications, Vol. X., No. I, 1877).

Staffordshire Clogg Almanacs. The full deciphering can be seen here.

It would be tempting to think that the ancient name of “Stafas”, meaning the smooth sticks on which such almanacs were cut, might have given rise to the name Staffordshire?

Folklore section from “Memorials of old Staffordshire” (1909)

A Web republication of:—

“SOME LOCAL FAIRIES”, from: Memorials of old Staffordshire (1909).

BY ELIJAH COPE OF LEEK.

WITHOUT making any attempt to account for the great amount of fairy lore in the moorlands of [north] Staffordshire, I will give a few typical examples and, where needful, what explanation seems necessary.

I stayed one night with an old woman named Grindy, who lived on a little farm near Mixon, in the hills east of Leek. After supper we had a long chat about old times and old people we had both known. We sat in a room she called the parlour, which was furnished with quaint old oak furniture, and some part of the room was wainscotted with oak panelling. As the weather was cold, and partly on account of my visit, a fire had been put in the quaint old grate. We sat till nearly midnight, and only a few pieces of wood glowed in the bottom of the grate. I was then startled by what seemed to be several raps on the table and one loud rap on the wainscot near the fire. The old lady did not pay so much regard to the noise as I did, but merely remarked that ” Old Nancy has come as usual.” I asked her who Old Nancy was. She replied that she was an old fairy who had been about there, goodness knows how long ; and that her mother told her about the fairies and counselled her to be good to them and always leave some bits of cake or other food either on the table or other convenient place in the house. Her mother had said that fairies were good and honourable little folk and would never steal anything so long as people were kind to them, and that they would do many bits of work in and about the house in payment for food. I asked the old lady if she had ever seen “Old Nancy ” or any of the fairies. “No,” she said, ” I don’t know that I have, nor have I any wish to see them. They don’t like people to watch them nor to interfere with them in any way.” […]

On the following morning we had an early breakfast, and I walked about the farm buildings, and tried to get up a conversation with a servant-man who was busy amongst the cows, but to all my inquiries about fairies, ghosts, and witches he gave a vague and evasive reply.

As a worker amongst oak for very many years, I don’t think there is any great difficulty in accounting for the noises on the table and wainscot. It is the nature of oak to swell in a damp or even cold atmosphere, and to contract in a hot or even warm atmosphere. The fire in the room had caused the oak to contract, and the noise was caused by its pulling itself away from its cross-bands.

Towards noon I started on my way home by Mixon Mines. I called at a cottage to see a Mrs. Frith, whom I cautiously drew into conversation about fairies. She put a shawl or wrap over her head and walked about half a mile on the way home with me in the direction of Mixon Hay farm. When in the second field from the village she pointed to the lower part of the meadow, and told me that her mother had spent hours there watching fairies dance round a ring, and had described the different coloured garments they wore. She said she did not think they were so very honest, for she had missed many articles of clothing which had been forgotten and left out on the garden fence all night; but added sympathetically, “Poor things, they must have clothes from somewhere and of some kind.”

The late Mr. Billing, who, some years ago, lived on a little farm on the hillside between Moridge End and Hollinsclough, was a firm believer in fairies. He was one of the few people I have met with who had seen them dance in a ring, and also seen them about the farm buildings. I learned from him many strange stories about fairies and their habit of taking babies from their human mothers and leaving their own children in the place of them. Such children are called changelings, or children that have been changed. The following story is a type of many. Most children who were ill-shapen, dwarfs, cripples, or otherwise deformed, and especially if they were lacking in speech, were supposed to be changelings! Mr. Billing told me that when he was a boy a poor woman, who lived at a cottage near him, gave birth to a baby that was perfect in every way, but very small. When about a month old, its mother took it into a hay-field and laid it on a heap of dry hay. As the sun was very hot, she put an umbrella over it. After about an hour or so she returned and found the baby asleep, but she fancied its features had changed. The dreadful thought came into her mind that the fairies had taken her baby and left one of their own in its place ! Worst of all it did not appear to her, judging from what she had heard about fairies, to be well born or aristocratic, but a common ” Hobthurst,” which is a fairy of low birth, low habits, and by no means industrious, but fond of sitting by the fire and leaning against the hob. She decided, however, to take it home, to be kind to it, and to treat it in every way as her own.

The child grew but little, and never learned to talk. Still she was very kind to it, hoping that some day or some night fairies might snatch it and return her own a wish that was never realised. Compensation, however, came in another way. One day, when clearing out an old cupboard that had been built into a recess of the house, she found a large number of gold coins wrapped in a piece of old linen rag. She was overjoyed at her good fortune, and thankful she had kept the child and been kind to it; for she was quite satisfied that the fairy to whom the child belonged had put the money there. For over three years she found money occasionally hidden in various parts of the house, chiefly in the thatch. Eventually, however, the child sickened and died, from which time, though she diligently searched, she never found a coin of any kind.

When Billing had finished his story, I asked him if he believed it to be true. “Certainly I do,” he replied with some warmth and drawing himself up to his full height. “Certainly,” he repeated ; “don’t you ?” I had to admit that there were some difficulties in the way of accepting it as true. “In the first place,” I said, “where did the fairies get their coins from? They either had melting-furnaces and dies to stamp their gold or they stole it.” My doubts quite offended the old man, who told me plainly that I was an infidel, and that he made it a rule never to give shelter to an infidel, which I took as a broad hint that I had better be going. He positively refused to shake hands with me or to say Good-night, but quickly said in a low voice, “All things are possible to Providence.”

Most fairy dances that I have heard of have taken place in low boggy ground or damp and undrained meadows, principally the former. The following, however, though of a common type, took place in the Victoria Gardens, which lie on the lower part of Leek, sloping northwards from the old church. A working man rented a piece of garden on the lower part of the ground. After his day’s work in the silk mill, he went to spend an hour or so weeding some vegetables. When too dark to see the weeds he went to his little wooden shed, or summer-house as he called it, lit his pipe, and sat for sometime thinking. Eventually he fell asleep. How long he slept he did not know, but it must have been nearly daybreak when he awoke. Going to the door of his shed he was greatly astonished to see a number of little people dancing round a ring, dressed in most gorgeously coloured costumes. Their motion was slow at first, but after a little time grew rapid. The man became excited, and went a few yards nearer to the dancers to get a better view of them. Still the motion of the dancers became more rapid, and in proportion the man became more excited, till finally, losing control over himself, he went close to them, and, clapping his hands together in applause, he called out, “Well done, my little folks, the one with the blue frock dances best.” The spell was broken, the dancing fairies vanished, and the man, standing near the spot where the fairies had been, rubbed his eyes in utter astonishment.

I remember when a boy walking with my grandfather from Ipstones to Leek, by way of Basford, and through the fields where stand the remains of an old stone cross. My grandfather took me a little out of the footpath to a field to show me some rings where fairies were said to dance. The rings were a little larger than an ordinary cart wheel, and the ground of a different colour from the other part of the field. Some time afterwards I paid a second visit along with other boys, and found the rings were gone. The farmer had given the land a dressing of gas-lime, which had killed the fungus that had formed the rings.

Probably the district most inhabited by fairies lies near the Bottom lane leading from Ipstones to Bradnop. There are several farms, mostly of small acreage, called Lady Meadows. The subsoil is clay and the ground wet, except in dry weather. Most fairies of that district seem to have been of a very industrious race. For a piece of cake and a bottle of home-brewed ale they found and restored to their proper places lost iron pins that belonged to ploughs. They prevented hedgehogs from sucking the milk of cows in the night-time. They were encouraged to be about the house by presents of tobacco and little delicacies in the form of food. Their little tobacco pipes were sometimes found in the fields, and the ploughman who turned one up whilst ploughing was said to be lucky. The ill-natured housewife who would not encourage nor reward their industry was often in trouble. Her oven would not bake bread properly; her knitting needles fell out; the flat-irons were either too hot and burned the clothes, or they were too cold and would not iron clothes properly. The things in the house were put in disorder in the night-time. Even her garters refused to remain fastened, and her hair would persist in falling down. The worst mischief, however, happened in the night-time. The farm dog would bark; crockery was found broken or damaged ; the cream was taken from the milk; the wife’s Sunday cap torn to pieces; and the husband’s tobacco stolen. In the end it paid the housewife to be generous and kind to the little folks.

I have often found that witchcraft and fairy lore have been linked together. Some of the witches I have known have blamed fairies for mischief reputed to them; as, for instance, when people could not make a light with the flint and steel, the mischief was sometimes charged to the fairies and sometimes to the witches, and occasionally to both. I have known and been intimately acquainted with witches, and have known and seen their methods of work, and what are called their black arts, which no respectable and well-bred fairy would descend to.

On the whole, I have found that fairies are respectable and industrious little folk, very harmless if properly treated, and though occasionally given to little acts of roguishness are by no means wholly bad. They are rapidly dying out. Education and science are making their existence intolerable. When they are entirely gone the world will be poorer by the absence of many moral stories told of them, and many high and noble lessons learned from their characters and actions.

[See also William Purcell Witcutt’s memoir “The Valley of Phantoms” (speaking of the late 1930s / early 40s in Leek).]