It’s good to see that the Majestic Chambers in the centre of Stoke town have been taken over by artists. I thought I’d rustle up a quick history of the site to celebrate. I’ve not done any deep research, this is just the result of a half hour among the online resources.

Outline history of Majestic Chambers (front, Campbell Place) and Majestic Court (rear, South Wolfe Street):

* Not to be confused with the former cinema next door:

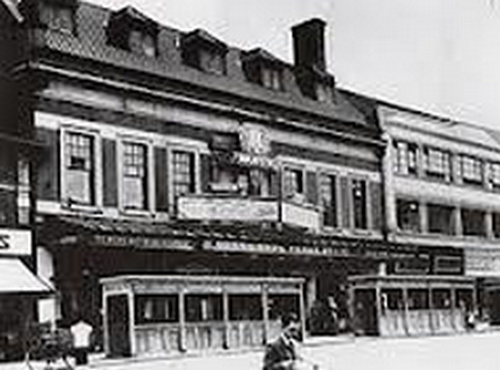

Majestic Chambers are not, as has been supposed by online forum chat, the site of the old ABC Majestic Cinema. As you can clearly see here from this circa 1930s photo, the current Majestic Chambers offices are off to the right of the cinema…

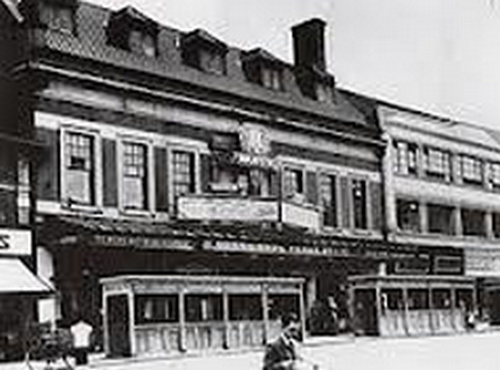

Top picture: probably 1930s? Bottom picture: showing The Dam Busters, 1955.

The structures outside the cinema appear to be to shelter the queues from wind and rain. Here’s a photo of the entrance in 1953…

Originally erected c.1914 as the silent cinema boom began, the cinema was named the Majestic Cinema. It seated 1,000 in two levels. It was taken over by ABC in late 1929, shortly after the Great Depression began, when it became known as the ABC Majestic. At that time internal changes were made, reducing the number of seats. The ABC Majestic closed — presumably due to television — on 30th November 1957. (My thanks to Midlands cinema historian “Richie” for these details).

Judging by the photos it looks to me as if the ABC Majestic cinema was in what later became Woolworths (and is now the Woolworths-clone shop BargainBuys). Woolworths opened in the town c.1928, but presumably it was only later — possibly 1957/8 — that they took on the old cinema site that they occupied until recently.

* Beresford’s toy shop:

The Sentinel once published memories of a Beresford’s toy shop that sat to one side of the cinema in the 1950s. The kids queuing up for the Saturday morning children’s cinema showings of children’s films (a sadly long-vanished tradition) must have have a fun time window-shopping as they went past the toy shop windows. Possibly Beresford’s was where the furniture shop is now?

Update, Dec 2017: My thanks to Terence Bate, who clarifies this last point…

“The full width of the frontage at ground floor level was part of the cinema. In fact the cinema occupied only a small central section of the ground floor frontage, and this was set back a considerable depth with shop windows on either side, Woolworths to the left and Beresfords to the right. Thus all were to the left of the Chambers. The cinema and toyshop were closed when Woolworths acquired the entire building and rebuilt their store on the site.”

* Majestic Chambers: 1926?

So, given all this information and the 1920s art deco frontage, a construction date of the 1920s seems likely for Majestic Chambers / Majestic Court. By that I mean, more likely than the c.1914 date of the cinema that was next door. Indeed, “1926” can be seen molded on the the ornamental drainpipe headers that adorn the Majestic Court frontage at the back of the building complex. A check of The Sentinel files on microfilm would give the exact opening date(s).

From the late 1930s to the 1950s the upper floors at Majestic Chambers appears to have served as purpose-built office space for professionals allied to the building trades, accountants, and similar professionals. These men had wonderful names, such as: A. W. Tonks, Fellow of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, who was there early 1950s; G. A. Barley of the Milk Marketing Board; Crofts the mechanical engineers, the Stoke branch of which was headed by a R. Moss; D. D. Jolly, P.A.S.I., a surveyor; and doctor A. Meiklejohn, M.D., D.P.H. There was also an industrial chemist, whose name I haven’t been able to discover.

As the city’s heavy industries declined or collapsed in the 1970s, from the mid 1980s the offices of Majestic Chambers became home to quasi public-sector organisations. Such as the Staffordshire Housing Association Ltd.; Groundwork Stoke-on-Trent (the environmental landscaping charity); and trainers of the unemployed such as Model Systems Training.

Today at 2013 the ground floor once again reflects its times; Greggs fast-food pasties and cakes; a pawnbrokers; a slick betting shop; a cheapo frozen food store. And, until taken over by artists this month, the upper floors were empty — having been previous occupied by another training firm for the unemployed.

However, independent shops do hang on, on that main shopping drag; there’s the cafe which does a fine cheap lunch; the computer parts shop; the card shop on the corner opposite Sainsbury’s; the ‘olde worlde’ sweets shop. All manage to compete with Sainsbury’s.

At the back of the building, across a courtyard, Majestic Chambers turns into Majestic Court. According to “Deltabus”, who once worked there, the right-hand ground floor of Majestic Court once housed the town’s Post Office while the left-hand side served as a butcher’s storage room. That was probably in the 1960s and 70s.

Update: Dec 2017. New postcard showing the Majestic cinema, which was then screening the romantic tragedy Miracle in the Rain (1956).

, with obvious resonances with my novel The Spyders of Burslem…