Archaic symbols from ancient Staffordshire token-coins (token-shape and all symbols from Eccleshall, apart from the stag and its pale-fence which is from Tipton), combined into a single design…

Author Archives: David Haden

Three Staffordshire tokens

Three of the most attractive and archaic-looking Staffordshire tokens (private-money coins), part of a large collection that is going to auction in September 2016.

“One does not simply walk into The Lord of the Rings…” – a viewing guide

Here’s my viewing guide for a full and chronological Lord of the Rings screen-experience. ‘Starting off’ with The Hobbit movie trilogy would be the worst possible introduction to Tolkien. Having seen the trilogies and key fan-films multiple times, this is how I’d suggest doing it in chronological order of events…

1. The excellent 70-minute fan-film Born of Hope, for the Aragorn back-story.

2. The Hobbit trilogy in the form of the 3.7 hour “Empty Sea Edit” bloat-free fan-edit movie, which is near-perfect up until the travellers reach Lake-town and tip out of their barrels (about two-thirds of the way into the story). After you encounter that scene, just stop watching the film immediately.

3. Then switch to Bluefax’s unabridged cast + music audio version of The Hobbit (free online at archive.org). Listen from Laketown arrival through to the point where they have arrived on the Lonely Mountain and Bilbo says to the dwarves “wait here…”, i.e. the point at which Bilbo is set to go down tunnel which forms the secret entrance.

4. Then back to The Hobbit screen trilogy, again in the form of the “Empty Sea Edit”. See the superb 15 minute ‘Bilbo and Smaug the dragon’ section. Stop watching as soon as that section finishes.

5. Then back Bluefax’s unabridged cast + music audio version to finish the story.

(Why? Because even the “Empty Sea Edit” can’t rescue the final part of Peter Jackson’s film of The Hobbit, and viewing this overwrought and emotionally-weak attempt to make a ‘Lord of The Rings 2’ will likely spoil a viewing of The Lord of the Rings trilogy itself).

6. Then the excellent fan-film, The Hunt for Gollum in its extended 38 minute version.

7. Then The Lord of the Rings trilogy in the extended DVD versions, but skipping entirely the long and bombastic exposition-for-dummies at the start of the first film. Instead, just start quietly in the Shire. Specifically, start with Frodo lying down under a tree in the woods, just before he first encounters Gandalf in the lane. (This nicely mirrors the similarly quiet Shire opening which the “Empty Sea Edit” gives to The Hobbit).

You’ll then want to pace yourself with well-placed breaks throughout the main 12-hour trilogy, or risk severe movie-fatigue which will spoil your enjoyment and comprehension of the story. This is especially true of the extended cut of the final Return of the King film in the trilogy, which deserves to be savoured with untired eyes.

All told, that lot should take you about 30 hours.

On John Buchan, the Lord of the Rings, and ebooks

The British author John Buchan’s works appear to have fallen into the public domain in January 2011. But you might not know it, as many are still way too difficult to find in the public domain as good e-copies. Still less as free audiobooks.

I’ve never really known anything about Buchan’s work, beyond the films of the famous The Thirty-Nine Steps. That brisk spy novel was apparently followed by two more, similarly set in the First World War, Greenmantle and Mr Standfast. So I had never thought of Buchan as anything but a rather dated spy novelist. But recently I read that a good case has been made that Buchan may have influenced The Lord of the Rings, via the historical novels The Blanket of the Dark (1931, Oxfordshire under a Sauron-like tyrant) and Midwinter (1923, a model for Strider and the Rangers), which are historical adventure novels set in olde England. For details of the seemingly well-founded claims see the recent way-too-expensive book of Tolkien scholarship Tolkien and the Study of His Sources: Critical Essays. So far I’ve only read the first chapter of The Blanket of the Dark, but it’s good and does have something of Tolkien about it. And yes, Tolkien read it. Like many intelligent people who work with text for a living, he did not care to relax with worthy-but-ponderous modernist slogs or the latest angst-filled wrist-slasher of a ‘socially-concerned’ novel. He preferred Haggard, Buchan, Chesterton, cozy detective mysteries, and in his later years he is known to have sampled science-fiction writers such as Asimov.

But what of Buchan? I now see that Buchan was an adventure novelist, military historian, supernatural tale-spinner, and generally a writer of vast scope. He died with over over 100 works to his credit, and was far more than just a spy novelist. A Scot, in historical adventure tales he seems to have followed in the tradition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped — long journeys through large landscapes, allowing full reign for Buchan’s talents in the description of landscapes. Such books were very popular at the time, pushing unadventurous boys and men into vast but precisely-realised wild landscapes beset by epic political intrigues. In America a similar approach was perhaps best exemplified at the time by Everett McNeil, who was the best-selling boys’ novelist of the time. McNeil was a follower of the similar and earlier Henty, and likewise sent boys on vivid epic journeys into the American wilderness and across the sea, in the company of famous explorers and soldiers. One can see how these sort of fresh and epic landscape-adventure novels, by the likes of Buchan and McNeil (and the earlier Henty), might have given Tolkien a star by which to steer The Lord of the Rings with.

Anyway, I thought I’d do a quick survey to see what is said to be most interesting among Buchan’s vast output.

First, the Scottish books seem to be ones to avoid as your ‘first taste of Buchan’. His first real novel, John Burnet of Barns (1898), is described as a novel of “doomed attraction across language and outlook”, and a lifelong rivalry that leads to… doom. Oh dear. It’s said by modern marketeers to be ranked alongside Kidnapped as a Scottish “adventure classic”, but frankly I never much liked Kidnapped as either book or film, and John Burnet sounds more of the same (only more gloomy and dour). John Burnet heralded a string of what sound like similarly depressing ‘Scottish local novels’ by Buchan, which one suspects are are probably now rather more fascinating to the Scots than to the rest of us. Buchan also edited an anthology of Scots vernacular poetry, The Northern Muse, if one wants to pile on some further misery.

Buchan seems to find the most readers outside of Scotland when he inserts a fresh element or two into Scottish life. Buchan’s Witch Wood appears to be a firm favourite of many, for instance, being a 1927 novel of devil-worship and evil forests in seventeenth-century Scotland. Knowing some of the context from my work on H. P. Lovecraft, at a guess I’d say the novel was probably inspired by Andrew Lang and/or by Margaret Murray’s The Witch Cult in Western Europe? At first I suspected that the devil worship would be of the tedious Wheatley-esque kind, very uninteresting to those used to the vivid Solomon Kane stories of R. E. Howard and the richly weird work of H. P. Lovecraft. But Witch Wood is apparently rather more subtle and interestingly macabre than the usual mumbo-jumbo, and was influenced via Blackwood and Machen. Buchan’s earlier supernatural story “The Watcher by the Threshold”, more ethnographic and found in the story collection of the same name, was apparently a forerunner of the novel Witch Wood. Be warned, however, that according to S.T. Joshi “The dialogue portions of John Buchan’s enormously long novel Witch Wood are almost entirely in Scots dialect”. Oh dear.

Other notable ‘weird’ novels are said to include The Dancing Floor and Sick Heart River.

Readers seeking similarly supernatural Buchan tales might look at Buchan’s story-and-poems collection The Moon Endureth: Tales and Fancies (1912, seemingly abridged in the American version), which came a decade after The Watcher by the Threshold. It has a manageable early sampling of his supernatural and mystery fiction including “The Grove of Ashtoreth” (Africa, haunted grove, ancestral taint) and some interesting historical-mystical poetry. His other two most notable supernatural stories can be found collected in the The Rungate Club book of club stories (1928). In this, his “The Wind in the Portico” (1928) sounds very similar in setting to Lovecraft’s famous “Rats in the Walls” of 1924. “Skule Skerry” (1928) has a scientist who encounters vast forces on a barren island, and it sounds similar to Blackwood’s famous “The Willows” of 1907.

His pamphlet-essay “The Novel and the Fairy Tale” (1931) isn’t online, but may interest those who enjoy Tolkien and the supernatural, and it seems that the essay was read by Tolkien in the 1930s. Update: It’s now online.

There is also a good deal of uncollected journalism by Buchan, who was also very much involved in political and military life, which in 2015 was surveyed by a a UWE PhD thesis. Novels such as his Prester John (1910) fit in here. It is not, as one might expect, a tale of the Crusades. Instead, it’s an early adventure novel set in Africa, which was published in the American ‘slick’ pulp magazine Adventure in 1910-11.

Lastly the Huntingtower has also been cited as a possible influence on Tolkien’s The Hobbit. It is apparently a lightweight boys’ adventure/spy tale and is another favourite of many Buchan fans. Like Buchan’s Witch Wood, an unusual element is inserted into Scottish rural/coastal life in Huntingtower. A band of unofficial self-organised Boy Scouts have come out to Galloway from the slums of Glasgow to camp, and they and the reluctant hero come into conflict with spies.

So, in conclusion, the ‘starter Buchan’ seems to come in three distinct clusters:

1) For the spy-novel fans, The Thirty-Nine Steps and its follow-on novels Greenmantle and Mr Standfast. All are on Librivox as free audio books.

2) For the fans of Blackwood-esque supernatural fiction, “The Watcher by the Threshold”, then the novel Witch Wood. Then his other main supernatural stories: “The Grove of Ashtoreth”; “The Wind in the Portico”; and “Skule Skerry”. There are no free audiobook readings of these, that I could find.

3) For the lovers of The Lord of the Rings, the novels Midwinter (1923) and The Blanket of the Dark (1931). Sadly there are no free or other audiobooks for these, and they’re only available as books from Project Gutenberg in Australia as .txt files. You’ll need to convert them for the Kindle ereader etc, via Calibre or Send To Kindle. I’d suspect that someone is still fussing around with a dubious copyright claim on these, which is presumably preventing their appearing on Archive.org and Hathi.

It should be added that several Tolkien fans who have read these through can be found remarking that the similarity does not seem too great to them. Possibly the academic who was making the connections was seeing things in them that a general reader would miss.

Swallows and Amazons, the film

On Tolkien at the Butts, near Newcastle-under-Lyme, in September 1915

I’ve been able to find more details about the claim made in the current gallery exhibition J.R.R. Tolkien & Staffordshire 1915-1918: A Literary Landscape (Shire Hall Gallery in the centre of Stafford, 25th October – 16th November 2016). I had been interested to read, in the exhibition’s press-release, that Tolkien had done some of his First World War training at Newcastle-under-Lyme in North Staffordshire.

I’ve since found this handy snapshot showing the map made by artist Hannah Reynolds (pictured) for the exhibition. It seems that Tolkien was indeed at the “musketry” training camp at Newcastle-under-Lyme. The dates for this, given on the map, are from 27th – 30th September 1915. Zoom in to the photo for the readable details.

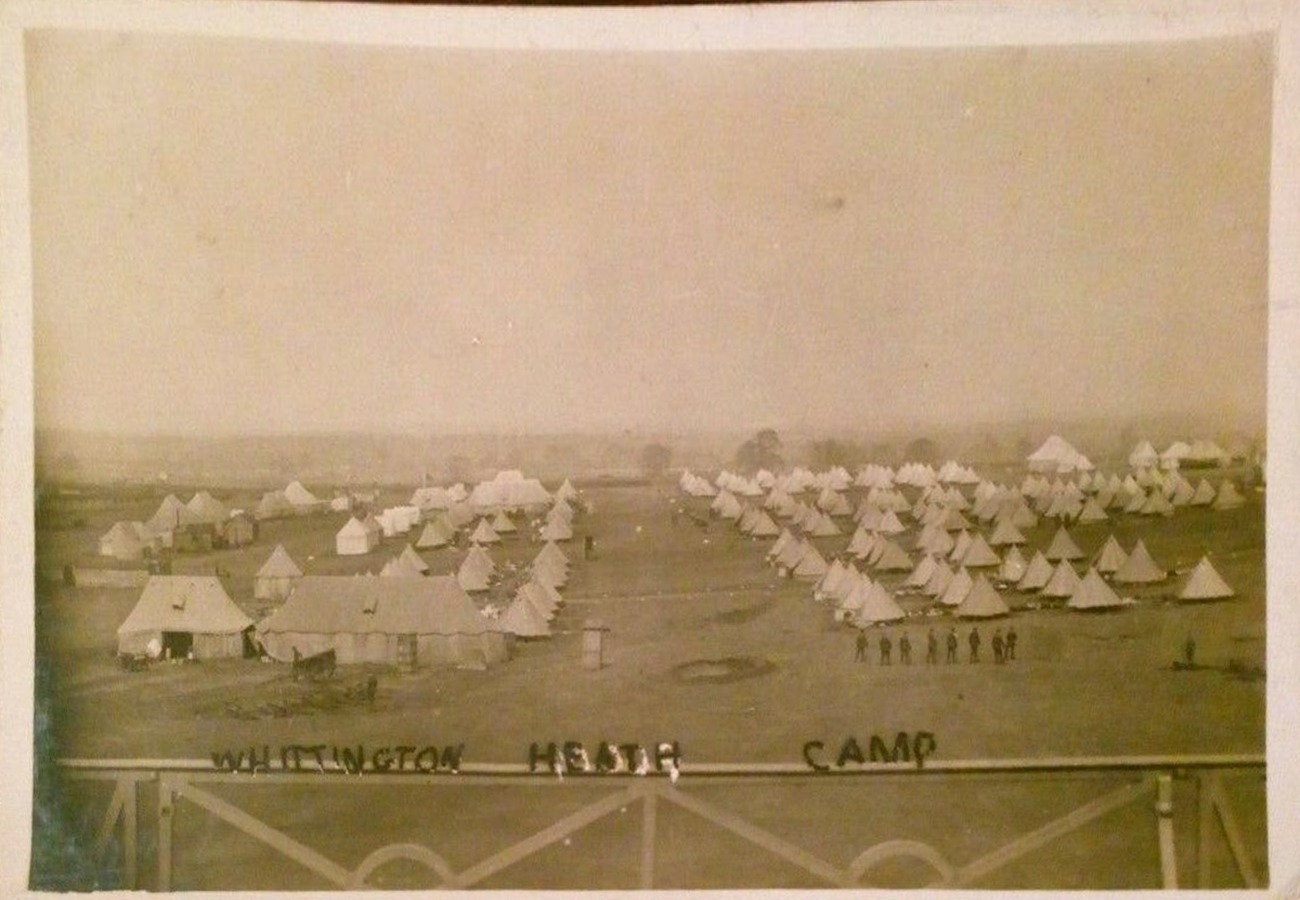

Picture: The Whittington Heath camp, located two miles from Lichfield. Probably also had officer huts by the time of the First World War.

Picture: The Whittington Heath camp, located two miles from Lichfield. Probably also had officer huts by the time of the First World War.

Having spent the weekend saying goodbye to his close friends at a hotel in nearby Lichfield, early on Monday 27th September 1915 Tolkien set off from his Lichfield camp into North Staffordshire. One assumes Tolkien led a march with his detachment of men, the distance being around 20-miles on fairly direct roads. If they marched rather than took a train, as seems very likely since they were doing basic training, then the logical half-way halt would have been at Stone. There Tolkien no doubt kept an eye out, on his map and on the road, for the early Mercian hill-fort (of King Wulfhere, whose chief priest was named Jaruman — a name very similar to Saruman). Tolkien was fascinated by early Mercia, and the fort is difficult to miss as it is marked on OS maps and dominates the ancient river-crossing just north of the town of Stone.

Tolkien and his men would then have continued walking northwards, through the increasingly impressive wooded landscape around Trentham, until they eventually arrived at the rifle training camp near Newcastle-under-Lyme. In 1915 the detachment would have been able to use the lanes and roads without fear of motor traffic. If they marched then they were lucky to march on the 27th, as the 28th was very wet across England.

The above map represents Newcastle-under-Lyme by using a picture of the town centre’s Territorial Force Barracks. The Barracks did indeed serve a local militia that had specialised in rifles for many years. Yet the town-centre Barracks could not have been where the firing of the “musketry training” was actually held. It was and still is a town-centre barracks, crowded in on three sides and facing a road.

Where then was Tolkien’s musketry camp? I was lucky enough to dig up the book Gooch of Spalding, Memoirs of Edward Henry Gooch 1885-1962. His military memoirs were kindly published by Gooch’s relatives in 2010, and Gooch usefully gives the exact details of the range and even its relationship to the camp at Lichfield in wartime…

Towards the end of the interview, the adjutant remarked, “Well now, I have got to punish you [Gooch] in some way. How would you like to command the Butts at Newcastle-under-Lyme?” giving a knowing wink as he said it. […] “There was no [rifle] range at [Whittington Heath, near] Lichfield and officers and men of the division went to Newcastle to fire their course [i.e.: test their training using live ammunition] before proceeding overseas. Officers came with detachments for a week’s musketry, then returned to their battalion, another lot taking their place. There was a competent sergeant-major [stationed at the Butts] to arrange everything, which relieved the officer of much to worry about.” (Gooch of Spalding, Memoirs of Edward Henry Gooch 1885-1962, un-paginated)

This was early 1915. The book shows that Gooch was in command of the Butts from the spring until July of that year, when he was sent to France.

The site of Tolkien’s camp is thus “The Butts” [meaning of the name] about two miles south-west of Newcastle-under-Lyme. The site had come to be a musketry camp when, in 1877, the Sneyd family estate had… “given land for the Butts, a rifle-range near or on Westlands farm, Newcastle-under-Lyme”. It thus seems quite possible that Tolkien never even saw the Barracks building in Newcastle-under-Lyme town centre, since wartime tents at the Butts were the likely accommodation in late September 1915. On the other hand, perhaps there were a few mornings when the camp’s junior officers would have gone to the Barracks for some specialist instruction in handling weapons? But we shall probably never know, now.

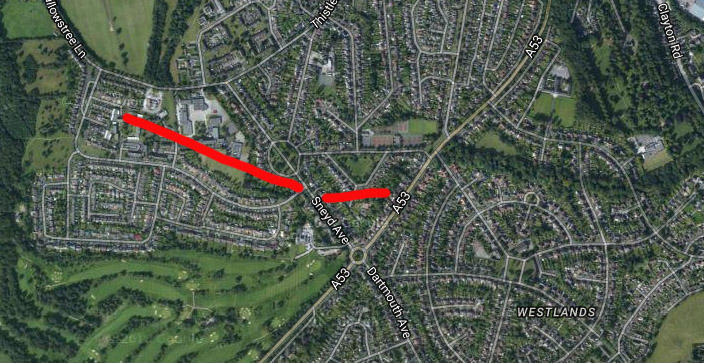

By laying the map over a modern satellite image one can show that the firing lines of the rifle and pistol ranges now sit under a mundane 20th century housing estate (the red lines, which have been slightly shifted off-line so that you can see the relevant bit of the photo), although some of the rifle range line looks like it may currently run through / along the south edge of a primary school’s grounds.

There is still an adjacent sloped area at The Butts, too steep to build on, which today can be seen abutting the western edge of the estate. This sloped area is still known locally as the Butts or Butts Walks. A local contemporary description of it says that…

“The Butts is a lovely steep hillside of green open space and large woodland overlooking a large residential area. It can be seen from around the Borough, is an excellent viewpoint over most of the urban area and [has views] to the Peak District [foot]hills 15 miles away.”

“Hills” must here mean views of the far outlier peak of Mow Cop, as the upland rises of the Peak District itself are (for some reason) never visible behind. Though perhaps they are in the very clearest weather. Nevertheless, this outlier hill and ridge was likely to have been Tolkien’s first glimpse of the upland Staffordshire Moorlands country in which the hero Sir Gawain seeks and then finds the Green Knight. Sir Gawain would later be his first major academic publication, in 1925. However, a straightforward influence is unlikely here, since at that time the scholarly consensus on Gawain was that the geographical setting of the story was very uncertain, perhaps Lancashire. It would take scholars another 20 years to start to tentatively suggest the Gawain tale’s main landscape setting could be in North Staffordshire. Many decades more would be needed to prove this beyond reasonable doubt and to start to identify sites.

Elizabeth: the Golden Age

If you want a good film to watch this Sunday, it’s “Elizabeth: The Golden Age” (2007). I’ve just seen it again, and it’s an utterly perfect fit with this moment in history.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekXX7u0gT3E?rel=0&w=420&h=236]

Burslem factory whistles

At the start of my novel The Spyders of Burslem, there’s a bit where the town’s pottery factory whistles all sound, as our hero moves through the town square. One of these whistles has now been restored and can be seen and heard on video here…

Otter’s Tears starts up in Burslem

A brilliant photo-story of how a derelict bit of a Burslem shop was transformed into a ‘craft ales’ place, Otter’s Tears. Find this new independent shop on Queen Street, near the School of Art and the Wedgwood Institute.

Update: Closed for good by the lockdown, in June 2021. But the beer continues to be sold online.

The Ballad of the White Horse – Malcolm Guite’s free audio reading

Here is Chesterton’s epic poem “The Ballad of the White Horse” (published summer 1911), in the best free audio reading I could find. The clear steady British voice of Malcolm Guite, Chaplain of Girton College Cambridge, carries the poem far better than Librivox’s worthy-but-flat American reader. Guite kindly offers .mp3 downloads.

If you have $15 there’s also a commercial reading for the American Chesterton Society, “Mackey’s Ballad of the White Horse”, which is by a long-time Chesterton scholar.

Picture: Eric Ravilious, “Uffington White Horse”, 1939.

Picture: Eric Ravilious, “Uffington White Horse”, 1939.

“The Ballad” is a grandly ambitious poem and is said by some to have been a possible inspiration for the general structure and tone of The Lord of The Rings. Tolkien was certainly in tune with Chesterton’s religious and political and localist stances. He had enjoyed and been swept up in the poem as a young undergraduate shortly after publication, which would mean circa summer 1911 – summer 1912. He then appears to have read the poem again in the wartime atmosphere of the early 1940s, when he found he was rather more critical of it. In 1944, re-reading it again with his daughter, he mused in passing that Chesterton’s “Ballad” clearly… “knew nothing whatever of the ‘North’, heathen or Christian” (letter of 3rd Sept 1944). He probably meant here the old Norse/Germanic ‘North’, but I also sense the implication that a sophisticated London man like Chesterton lacked the grit and deep regional knowledge needed to really ground his poem in the Englishness that Tolkien knew from his background in Birmingham and the West Midlands.

“The Ballad” had an equally inspiring literary influence on Robert E. Howard (author of the Conan stories), from 1927 onward. The opinion of R.E. Howard’s friend H.P. Lovecraft on “The Ballad” is unrecorded, though doubtless Howard would have mentioned it favourably to the Anglophile Lovecraft. In his youth Lovecraft had certainly admired Chesterton’s incisive and knowing wit and his keen observations on aesthetic matters, as well as a few of Chesterton’s better detective stories. But Lovecraft later found Chesterton’s rejection of Darwin’s science, as late as 1920, to be risible (“when a man soberly tries to dismiss the results of Darwin we need not give him too much of our valuable time”). In early 1930 Lovecraft had the opportunity to hear the elderly Chesterton speak in New England, but he didn’t bother. He felt that Chesterton had turned his back on the unsettling discoveries of the emerging modern world and had become an old fossil trapped in the pungent amber of 1920s Catholicism (“synthetic Popery”) and a fading late-Victorian arts-and-crafts tradition (a “crazy archaism”) which claimed the 13th century to have been the pinnacle of civilisation.

Peak Kitty

Collections in the Landscape has a new blog post on “Peak District Cave Lions!”. Oddly enough I made a picture of such a few weeks ago (background is a public-domain picture from Wikimedia)…

The articles also touches on aurochs, huge wild cattle that survived at least until Roman times (possibly a bit later) and whose gene pool fed into modern cattle breeds.

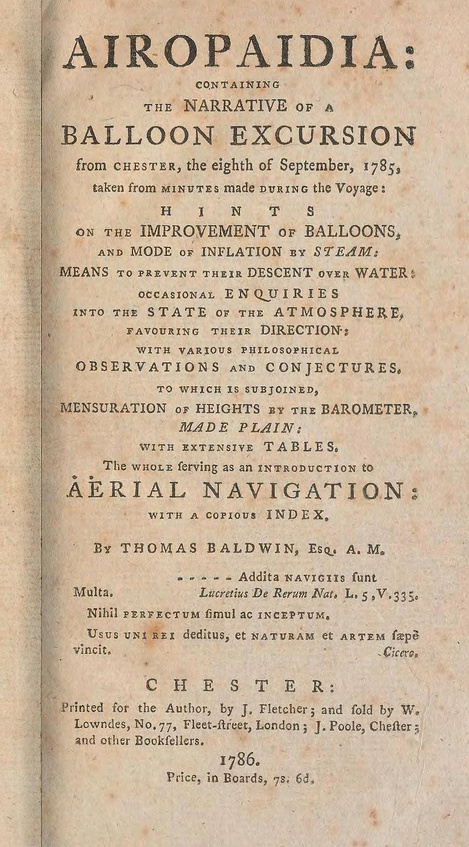

Airopaidia, 1785

Airopaidia. A 1785 account of how a brave aeronautic artist, Thomas Baldwin (1742-1804), became the first to describe and sketch in detail seeing Chester and its environs from the air…

“Things taking a favourable turn [in the ascending balloon], he stood up, but with knees a little bent — more easily to conform to accidental motions, as sailors when they walk the deck — and took a full gaze before, and below him. But what scenes of grandeur and scenes below! A tear of pure delight flashed in his eye, of pure and exquisite delight and rapture; to look down on the unexpected change already wrought [below him] in the works of art and nature, constrained to a [single] span [of the eye] by the new perspective, [and] diminished almost beyond the bounds of credibility.”

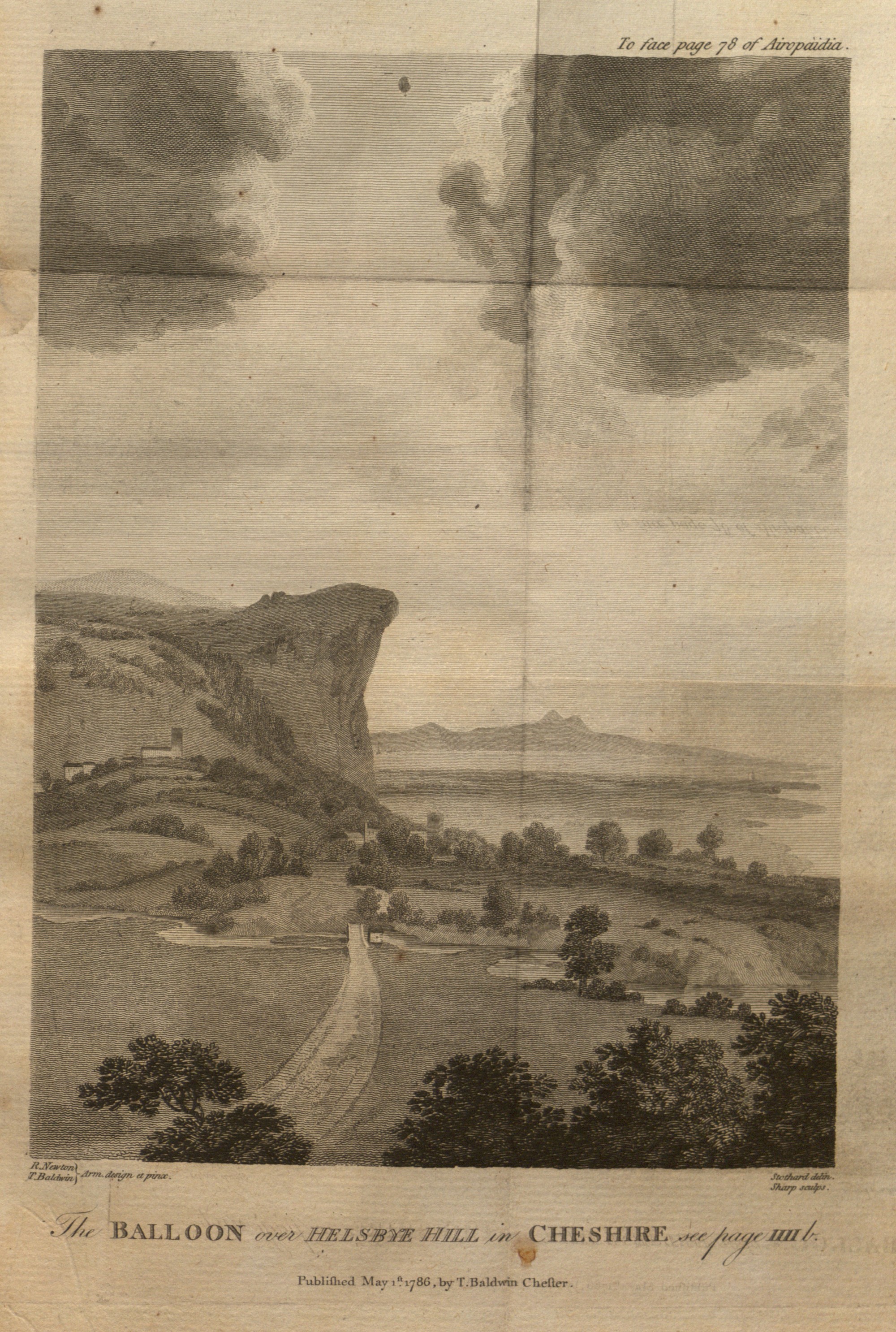

A dramatised painting of the balloon in which Baldwin ascended. The paddles were either removed or not used for Baldwin’s flight, and the shape of the balloon was probably rather longer and thinner than the perfect sphere depicted by the painter…

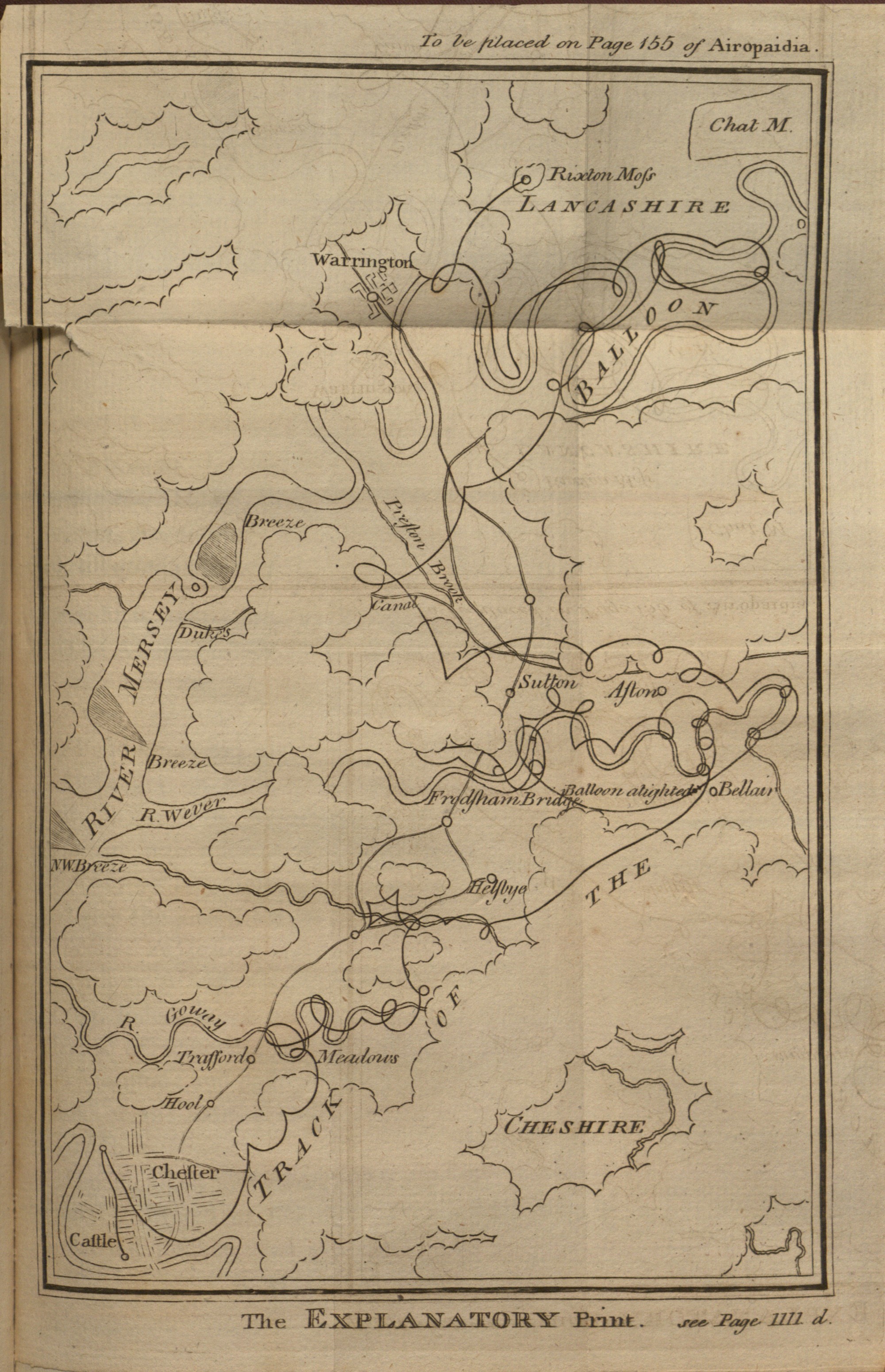

He flew twenty-five miles, and landed somewhere on Rixon Moss…

He’s probably unique in trying to visually convey to the public the top-down perspective. His colour depictions of the downward view must have been a very unusual pictures, for those who first saw them. Of course, they would have seemed somewhat similar to the top-down perspective of maps. But to see something like this must, at first, have been baffling…