William Holloway’s A General Dictionary of Provincialisms (1838) in the British Isles. PDF version is not OCR’d.

Author Archives: David Haden

People of the British Isles

From Wellcome, the University of Oxford, and UCL, the first fine-scale genetic map of the British Isles. This definitely settles some long-standing debates and also bolsters common folk understandings of boundaries…

* “the Anglo-Saxons intermarried with, rather than replaced, the existing populations”.

* “there is no obvious genetic signature of the Danish Vikings” — and even up in Orkney the Norwegian Vikings are only at 25% of the DNA, which is congruent with raiding rather than robust over-wintered settlement. Very interesting, and perhaps the most unusual finding. Perhaps a strict Danish Viking religious prohibition on siring inter-bred children could explain this?

* “a substantial migration across the channel after the original post-ice-age settlers, but before Roman times.” Presumably this means the mysterious but relatively short-lived ‘Beaker people’ influx and then the later pre-Roman Gaulish Belgic tribes such as the Cantii (Kent) and the Regni (Sussex and Surrey). The latter pressed across the Channel and somewhat up into southern England, displacing the south-coast natives over to London in the east and Cornwall in the west. That would explain, as the new findings state, “why the Cornish are much more similar genetically to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or the Scots.”

* there’s no discoverable Roman genetic presence, or of their variously-recruited legionnaires or slaves. Maybe they really did all go home as the Empire withdrew from the British Isles?

* “The Welsh appear more similar to the earliest settlers of Britain after the last ice age than do other people in the UK.” That fits with other genetic studies from 2006/7, which found that the Celts had started moving north from the Basque country to colonise all along the Atlantic coast as far north as Ireland and western Scotland, a migration completed into Ireland circa 1,700 BC. But the new Wellcome study appears to show that the south-to-north migrating Celts never fully penetrated the difficult terrain of inland Wales, even once they were settled along that part of the British Isles.

* English areas have maintained their “regional identity for many centuries”, and many broadly map onto the old English counties and onto long-standing regional grassroots understandings of boundaries. Cumbria vs. Yorkshire, Devon vs. Cornwall are sharply distinct genetic regions, for instance.

The report can offer no indication of where the Mercian Anglians may have come from, or who they really were on the continent (Vandals, Goths, Frisians?). Continental DNA sampling is apparently patchy at present, and sometime outright outlawed, and the study didn’t look at the Netherlands. Where Ghent was a Vandal city, for instance.

The study papers and maps can be found at: People of the British Isles.

Update: Two years after this post in 2018 there was a a new study of 400 instances of degraded DNA from skeletons across Europe, to claim a supposed “90% replacement” of the British by circa 1,000 B.C. This was apparently by immigrants from central and northern France, who apparently had fairly recently originated somewhere on the steppes of Eastern Europe before sweeping westward into Central Europe and replacing the natives. But the Welcome study and a mass of other British and historical evidence contradicts this claim. The scientific consensus is still that the British date back to the Mesolithic, and that we do so in a fairly stable continuity. One way, I would suggest, to encompass the new “90% replacement” claim would be to assume that incomers did arrive and that they were buried rather differently than the natives. Thus, we would have more of their remains in a form amenable to DNA extraction, which would skew the picture.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Vision of Freedom

There’s an entertaining and well-delivered recent Acton Institute podcast on Tolkien’s political stances, “J.R.R. Tolkien’s Vision of Freedom” (major plot spoilers). Be warned that the sound quality at the start is terrible. The lecture itself starts at 3:48 minutes, using a different microphone, and from then on the sound becomes much better.

It’s a very illuminating lecture, and didn’t drift off into the usual tedious American think-tank concerns about: ‘… and how does this relate to the Constitution and the Founding Fathers?’ The speaker’s grasp of both The Lord of the Rings and British history is obvious somewhat superficial (at one point he forgets the names Merry and Pippin, and never mentions the roots of Tolkien’s ‘conservative anarch’ politics in the lived experience of pre-Norman England), but otherwise the lecture seems soundly based. After listening I can certainly see an additional political aspect to the initial tepid reception of The Lord of the Rings in the Cold War of the mid and late 1950s. Soviet agents and communist sympathisers were in key positions in British literary life at the time. The publication of Orwell’s Animal Farm for instance, was repeatedly blocked by what we now know to be Soviet ‘sleeper’ agents. One wonders how this influenced the reviews for The Lord of the Rings, though one also has to wonder how many of those early reviewers actually read the book, let alone got all the way to “The Scouring of the Shire”. The same problem also informs the more recent sour reception of the movie adaptation, among leftists and Guardian readers.

The lecturer also has a whole book on the topic, for those who need the details and the footnotes, The Hobbit Party: The Vision of Freedom That Tolkien Got, and the West Forgot. This has a deeply off-putting title and cover, which I presume were somehow meant to ‘attract the Harry Potter generation’, but with the unintended consequence of making everyone else cringe and flee. Nevertheless, the book has been well-reviewed, and it’s definitely not another ‘Shopping Lists of the Inklings: a Lacanian analysis’.

The Runic Poem’s “moor-stepper”: Orion

I saw the constellation Orion rising in the dawn sky, standing up and rather fine, this morning at 6.30am. So I thought I’d make a suggestion that might put right a misconception, about the nature of the “moor-stepper” found in the gnomic “Ur” Runic Poem (pub. 1705). Especially for the benefit of any pagans out there, who according to my cursory searches appear to think it was a Grendel-like monster or a wild auroch (extinct type of wild bull).

Runic Poem, original:

U | [ur] byþ anmod and oferhyrned,

felafrecne deor, feohteþ mid hornum,

mære morstapa; þæt is modig wuht.

Charles William Kennedy, 1910, in the “Introduction” to the best translation of Cynewulf:

U | [Ur] is headstrong and horned, a savage beast. With its horns the great moor-stepper fighteth; that is a valiant wight.

My translation:

U | is steadfast has horns above all,

a very savage beast, fighting with its horns,

great mere-stepper; that is greatly spirited.

Picture: Simplified design based on Orion shown in the Firmamentum star atlas, 1690 AD. He steps into a mere, a spring-fed mere-pool that feeds the river constellation. (This is a .GIF image and may not appear if you have a GIF blocker).

Picture: Simplified design based on Orion shown in the Firmamentum star atlas, 1690 AD. He steps into a mere, a spring-fed mere-pool that feeds the river constellation. (This is a .GIF image and may not appear if you have a GIF blocker).

Having seen Orion this morning I can say that his stepping pose is quite obvious to the star-gazer. So I’d suggest it’s not only a moor-stepping bull in the Runic Poem. It’s also Orion, who is frozen in the pose of stepping up. The “mere” is the (assumed moorland) mere-pond that feeds the river constellation, into which he steps in order to face the bull. He is at a disadvantage in the fight, due to the terrain, not to mention the gigantic bull. The trickster hare gives him ‘a leg up’ on her ears, and lets him borrow her back legs for a moment, with the implication that he may be about to spring over the bull’s horns.

My use of “greatly spirited” is more subtle than Kennedy — since the lines are meant to be a sort of night-sky riddle. So there’s no need to blatantly spell out that to the reader the supernatural aspects. The implication of the lines is that both the Bull and Orion are “greatly spirited”, and that they both exemplify the ‘fighting spirit’ in the rune Ur. The word “wight” was also avoided because modern readers now understand “wight” as being connected to Tolkien’s “barrow-wight”.

Orion’s rising (as a wintertime standing figure) traditionally heralds the autumn storms — “the storms that annually attend the heliacal rising of Arcturus and Orion” (Bede, drawing on Job in the Bible). Thus, the runic Ur is also the associated “greatly spirited” storms and winds. Thus we get the name, presumably, Ur-ion.

The Ur rune might be thought of in terms of man’s bravery and courage, in the face of implacable fury. Not in terms of the rather lumpen modern pagan suggestion that: “durh… Ur means a mad cow, dude!”

It’s then a dual-pronged rune in meaning as well as design: consider for instance the military distinction made between the two types of battlefield bravery: mad foolhardy rush-at-’em bravery, and considered bravery that is brought forth from within oneself in the face of an implacable opposing force. Only the latter type gets medals.

There is a sound-play in the rune poem (given above) between mǽre (‘great’, ‘monstrous’, ‘boundary’, ‘mere (pool)’) and the following word morstapa (‘ranger in-the-wilds’, ‘Orion’). If the Runic Poem was a mnemonic for teaching people the runic alphabet and then helping them to recall its subtleties, this would be a kind of test for them. The choice of meaning that a student has to bravely declare to the teacher (‘it’s just an angry bull’) thus encapsulates the choice a brave man must take in battle, in weighing the evidence and then pressing forward bravely regardless of the known risk. The correct student should emulate this type of subtle military decision-making, before he makes his brave call on the gnomic meaning of the lines (‘actually it’s the Bull and Orion, and is about the two types of bravery’).

Incidentally, “modig” = ‘spirited’ in the Anglian form. Which implies the Runic Poem may be Mercian, or at least copied there by a scribe, because in other territories modig was only used religiously and later. (The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume 1, p. 343).

I can call an eminent philologist to my cause here. Bosworth obviously also thought the morstapa wasn’t the wild bull itself, but rather a man ranging into the wilds to fight it…

Mor-stapa, an; m. a moor stepper, a desert ranger (A Dictionary of the Anglo-saxon Language, 1838)

Compare also the Roman writer Manilus (d. 384 BC) on Orion (Jewish: gibbor, ‘the giant’; Arabic: ‘the hero’). To him this sky-deity makes… “Smart souls, swift bodies, minds busy about their duty (officium), hearts attending all problems with speed and indefatigable vigor”. (A.E. Housman trans.) Also Thomas Hood of Trinity College, Cambridge (1590)… “the reason why this fellow was placed in heaven, was to teach men not to be too confident in their own strength.” Horne, famed for his deep study of Orion and his three-volume epic poem on the topic, also has in his Introduction… “Orion is man standing naked before Heaven and Destiny, resolved to work as a really free agent to the utmost pitch of his powers…”.

Tolkien might have nodded to the -or part of Gibbor in The Lord of the Rings… “as he climbed over the rim of the world, the Swordsman of the Sky, Menelvagor with his shining belt. The Elves all burst into song.”

Finally, I’d also note that the bottom half of Orion with his ‘stepping’ leg looks like the shape of the Ur rune….

Picture: Malton Pin, 10th century northern England (my crop of the British Museum’s photo of the cleaned brooch); and a modern simplified version of the rune.

Picture: Malton Pin, 10th century northern England (my crop of the British Museum’s photo of the cleaned brooch); and a modern simplified version of the rune.

Sources for the 1915 Taliesin controversy

For the convenience of current and future scholars and poets, here are the key source texts of the 1915-1924 Taliesin controversy in chronological order:

1. John Gwenogvryn Evans, Facsimile & text of the Book of Taliesin, 1916.

2. John Gwenogvryn Evans, Poems from the Book of Taliesin, 1916. Complete translations by Evans from the original manuscript, completed over seven years. Evans had been a speaker of Welsh in Carmarthenshire until age 19, when he learned English, but thereafter lived in England (he later retired to Wales).

Note that, “Though thus dated [1910 and 1915 respectively], the volumes [above] were not issued until 1916.” — Y Cymmrodor, 1918.

3. The Athenaeum, 1916, issues 4601-4612. Review by Quiggin of Evans’s book editions of Taliesin. A substantial section is given in Y Cymmrodor, 1924.

4. John Morris-Jones, Y Cymmrodor 1918, Vol 24. A substantial attack on Evans for his edition of Taliesin, and with a very strong Welsh nationalist flavour to it. The review was assisted by Ifor Williams. See Evans’s 1924 rebuttal.

5. Gilbert Waterhouse, The Year Book of Modern Languages, 1920. Annual review of the recent Celtic literature, and which addresses the dating of the life of Taliesin. “John Morris-Jones undertook to review Dr Gwenogvryn Evans’ two volumes on Taliesin [but he supports] his linguistic arguments with rather slender palaeographical evidence”. (At Google Books in Preview).

6. John Gwenogvryn Evans, Y Cymmrodor 1924, Vol. 34. Evans’s book-length reply to his 1918 critic.

7. Obituary of John Gwenogvryn Evans, J. Vendryes in Revue celtique 47, 1930.

8. At 2016 Angela Grant has recently completed a thesis at Jesus College, Oxford: “The View from the Fountain Head: the Rise and Fall of John Gwenogvryn Evans”.

Liverpool Hope University – free Tolkien Day

Liverpool Hope University has a free Tolkien Day of talks on 11th November 2016.

“Speakers on the day include John Garth, author of Tolkien and the Great War, Edmund Weiner, co-editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, Liverpool Hope University Alumnus Lord David Alton, and Stuart Lee and Elizabeth Solopova from the University of Oxford.”

Looks like an interesting speaker roster…

* Fairies, Goblins & Britain: Tolkien’s ‘Goblin Feet’ (1915, the early wartime faerie poetry)

* Tolkien’s Manuscripts

* Tolkien’s views on children’s literature

* Diction and narrative in ‘The Lord of the Rings’

* The Great Wave (he had a recurring dream of a Great Wave)

* Tolkien and Faith

* Alan Lee (Tolkien artist)

It’s free, but it’s on an awkwardly-placed campus outside the city centre, and requires a rail traveller to take a bus through inner-city Liverpool from Liverpool Lime Street station. Not an enticing prospect at the end of a 90 minute rail journey, for someone who doesn’t know Liverpool and loathes bus travel. Doing it via a taxi would bump the total cost to £40 (rail + taxi), which is too expensive for me. Oh well. But, hopefully there will be podcast recordings available online after the event.

Interestingly, the press blurb for the day remarks that…

“Tolkien was part of a team based at what is now Liverpool Hope University, who translated and edited The Jerusalem Bible. The Jerusalem Bible was the first translation of the whole Bible into modern English (1966) and celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. Tolkien’s translation of The Book of Jonah is admired for both its beauty and accuracy.”

Fascinating, I never knew that. A perfect fit of course, what with his long-standing interest in the sea and mariners. Although according to Carpenter his text was a translation from French and not the Hebrew, and once delivered it was then “extensively revised by others before publication”. Still, his pre-polishing manuscript of The Book of Jonah is available. It was published as a book in 2009.

A Scottish riddle, Hobbity-bobbity

A Scottish riddle, published 1881 in Notes on the Folk-lore of the North-east of Scotland (Folk-lore Society). As far as I can tell it doesn’t seem to have been noticed in the assiduous search for the origin of the word “Hobbit”…

Q: “Hobbity-bobbity sits on this side o’ the burn, Hobbity-bobbity sits on that side o’ the burn, An gehn ye touch hobbity-bobbity, Hobbity-bobbity ‘ill bite you ?”

A: “A nettle.”

Sleeping Green Man ceramics from Oddbods

Lovely archaic “sleeping vegetation god” ceramics from Loughborough’s Oddbods Pottery. The artist seems to be taking the English ‘wide awake’ Green Man further back in time, toward the sleeping-and-rebirth of the very earliest-known of such gods, Tammuz of Eridu…

“Tolkien” (if he ever existed) did not “write” this work in the conventional sense

A delightful ‘biff on the nose’ to parroting literary academics and over-cautious politically correct historians, from Catholic World: The Lord of the Rings: A Source-Criticism Analysis…

“Because The Lord of the Rings is a composite of sources, we may be quite certain that “Tolkien” (if he ever existed) did not “write” this work in the conventional sense, but that it was assembled over a long period of time by someone else of the same name. We know this because a work of the range, depth, and detail of The Lord of the Rings is far beyond the capacity of any modern expert in source-criticism to ever imagine creating themselves.”

In case you’re skim-reading this: it’s a joke.

The Lyonesse Project – final report published

Funded by Historic England, a scientific research team has been looking into the historicity of the legendary Cornish Lyonesse. Early medieval historians had noted memories of a very large tract of land that was said to have slipped into the ocean off Cornwall, once extending across “one hundred and forty churches and a forest”. Since then Lyonesse has regrettably attracted wave after wave of swivel-eyed madmen, who have enfangled it with UFOs, psychic super-civilisations, dragon-headed spiritualists from Tibet and similar utter lunacy, until it’s become near impossible to even find the first historical accounts of the legend online. Thankfully the Encyclopaedia Britannica has it straight…

“… since the 13th century [there have been accounts] that concerned a submerged forest in this region, and a 15th-century Latin prose work, an account of the journeys of William of Worcester, makes detailed reference to a submerged land extending from St. Michael’s Mount to the Scilly Isles. William Camden’s Britannia (1586) called this land Lyonnesse, taking the name from a manuscript by the Cornish antiquary Richard Carew.”

Now six years of archaeological and seabed scientific work by the CISMAS Lyonesse Project has rigorously investigated the matter, albeit somewhat under cover of the hot topic of ‘sea-level rise’. The project has just published its final report, The Lyonesse Project: a study of the historic coastal and marine environment of the Isles of Scilly.

Their research has found that the Isles of Scilly were indeed a single large island 9,000 years ago, and that two-thirds of the island’s land mass was then submerged over a period of just 500 years between 2,500 and 2,000 BC (presumably with no CO2 involved, hem hem…). The team found “a submerged forest”, just as the 13th-15th century Lyonesse story had it — though no submerged land-bridge between the Scillies and St. Michael’s Mount in Cornwall. There were, of course, no churches to submerge at that time, though one imagines that “one hundred and forty” submerged stone circles might be a possibility.

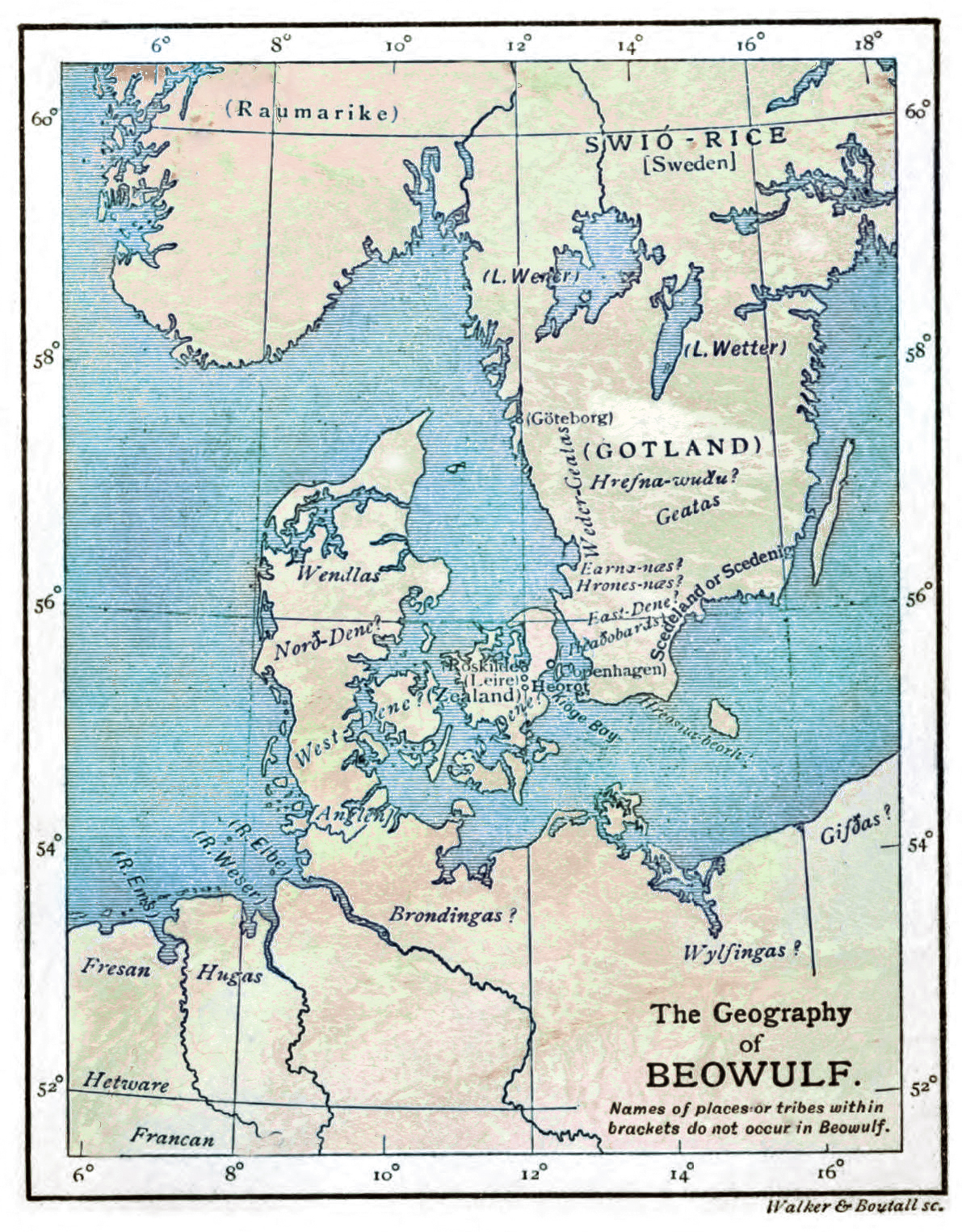

Map of Beowulf

A 7th century rock-cut warrior grave and bowl at Barlaston

I’ve just been fascinated to learn that there was a “rock-cut flat grave”, probably interred in the 7th century AD, found in the early 1850s near Stoke-on-Trent. Specifically cut into red sandstone somewhat near the River Trent at Barlaston, now a large village on the south edge of Stoke-on-Trent. My thanks to Steve Booth of Stone for telling me of this. It’s possible I had read of it while writing my history of Burslem and the Fowlea Valley, which was many years ago now, but had then considered it a little ‘out of area’. Now the grave perhaps takes on a new significance in the light of the Staffordshire Hoard discoveries, so I thought a quick summary would be in order to save other people some time. Here’s what I was able to find via the Web, put into a rough order:

THE FIND:

The British Museum has a full summary account of the bowl and states that…

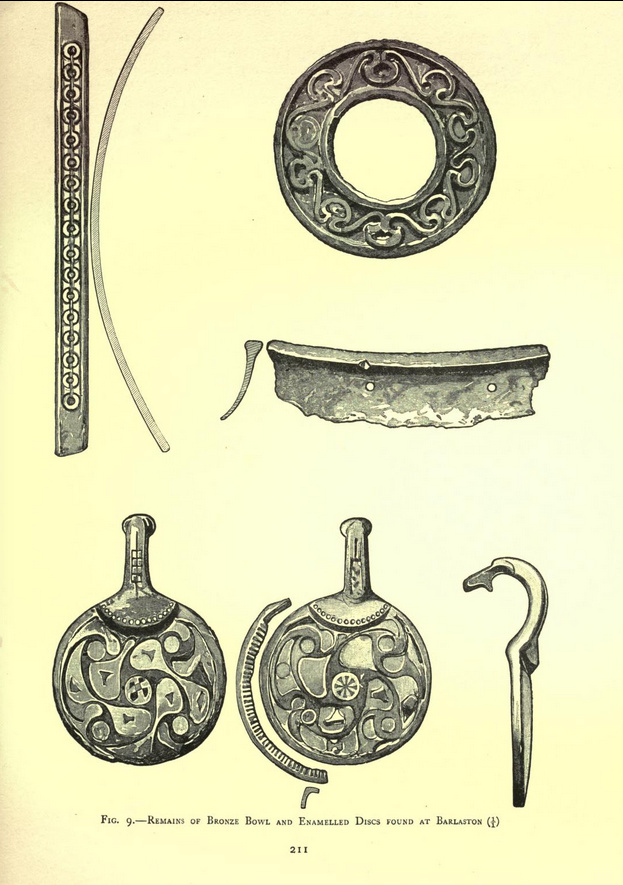

“The bowl fragments were found accidentally while planting trees on the Wedgwood estate in about 1850.” The find was written up by “Lawrence Wedgwood, FRGS, who had been present at the discovery [circa 1851], wrote a short report of the find, published in 1906 [when] Miss Amy Wedgwood caused an iron fence to be erected round the site of the grave to mark its position. […] An admirable account [of the bowl] was provided by Romilly Allen.

Allen adds a first-hand account had from Amy Wedgwood stating that the planting of the trees had been on… “the gravel-pit hill behind the house”. This confirms the location given in Lawrence Wedgwood’s paper (given in full, below).

THE GRAVE:

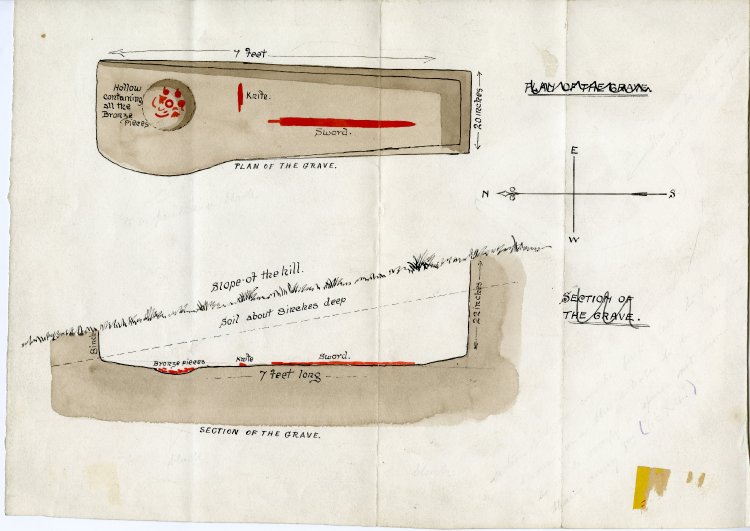

While the find was initially by workmen, it was very well documented considering the date was the 1850s. The burial was found along with a sword and a knife, the weapons indicating a male burial and very probably a warrior. The size of the 7-foot grave also indicates a male. The bowl was placed at the north end of the grave and found as bronze fragments in a depression. There was no trace of a barrow mound (tumulus) in the heavily ploughed land and no other graves were found nearby despite extensive tree-planting. The British Museum kindly offers a scan of the plan made for the site…

The grave was found without any trace of bones, and in the 1960s a cremation was mooted to explain their absence.

THE BOWL:

The book Roman and Celtic objects from Anglo-Saxon graves: a catalogue states that… “The vessel was found near complete”. The British Museum photography of the fragments of the bowl suggests such a phrasing is misleading to the layman, who may then expect to see the “near complete” shining bowl rather than fragments…

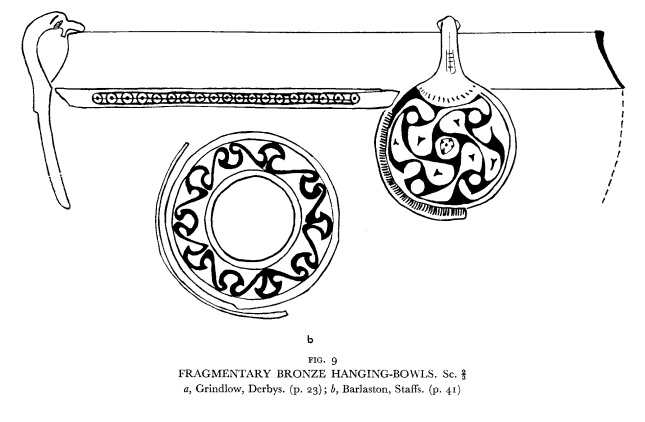

Ozzan also gives a line-drawing of the bowl’s reconstruction, confirming the fragmentary nature, and also notes that… “the bowl has been spun, not cast”.

The Victoria History of the County of Stafford also gives a good drawing (p.211) of the bowl…

Some Victorian antiquarians initially thought, wrongly, that the bowl fragments may have been from a helmet. Such as Llewellyn Jewitt in his Grave-mounds and Their Contents: A Manual of Archaeology, a book in which he also described the other fragments found in the Barlaston grave.

The Romilly Allen description is also online in open access, in a scan of Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. Although the illustrations of the disc designs appear to have been removed from the scanned Harvard library copy. Allen was of the opinion that the disc patterns were very early, reflecting the influence of late Celtic work. Ozzan later suggested an Irish influence (see quote below) on the discs via their enamelling.

DATING:

Audrey Ozzan in the article “The Peak Dwellers” is not entirely sure that the Barlaston bowl is 7th century, but is fairly sure…

“… the Barlaston bowl is of the simple type, but there are strong reasons for regarding it as seventh-century. Simple bowls from Faversham (Kent) and Hildersham (Cambs.) belong to a group which Haseloff places ‘in the first half of the seventh century and perhaps also in part of the sixth’; and the Hildersham bowl was associated with a shield-boss of seventh-century type. [… Though notes that the dating to the 7th century seems to be confirmed by] a recent paper suggesting that the Irish techniques of enamelling and millefiori found their way into English contexts by way of monastery workshops in England.”

SIMILAR BOWLS:

The Victoria History of the County of Stafford notes (p.210) three other bowls (perhaps of somewhat different dates) in nearby Dovedale in the Peak…

“Though an isolated burial the Barlaston discovery falls into line with others made just across the Derbyshire border. Remains of no less than three such bowls have been found in the neighbourhood of Dovedale: at Middleton-by-Youlgreave [an ‘east-and-west burial on Middleton Moor’], Over Haddon, and Benty Grange, the last lying in the grave beside the hair of a warrior, in association with a leather bowl ornamented with applied crosses. At Barlaston the bowl was found just where the head would have lain, and seems to have been in the centre line of the grave, so that perhaps the head rested within it at the time of burial.”

Audrey Ozzan’s article “The Peak Dwellers” notes that…

“only one Staffordshire barrow [that] affords an unequivocally seventh-century find. This is one of the barrows on the Cauldon Hills (Carrington, 1849), which contained an inhumation, sex and orientation unknown”

The latter find was by Thomas Bateman, recorded in his Ten Years’ Diggings in Celtic & Saxon Grave Hills (1861)…

“CAULDON HILLS. We afterwards opened a barrow on Cauldon Hills, in a lower situation than those before examined there. One-half had been removed down the level of the adjacent land…”

RECENT WORK and WIDER CONTEXT:

I note that there is a thesis on such English bowls by Jane Brenan, and from it the slightly revised book Hanging Bowls and Their Contexts: An Archaeological Survey (1991).

WHO WAS HE?:

Even by the mid 1960s Greenslade and Stuart’s A History of Staffordshire (1965) considered it rather a mystery in terms of its location and lack of immediate surrounding context…

“There is, however, one isolated burial at Barlaston, close to the [River] Trent south of Stoke, which has not yet been satisfactorily explained.”

Bury Bank and Saxon’s Lowe are fairly nearby. Bury Bank is associated with King Wulfhere (658-675 AD) and has never really been properly investigated. There might equally be some connection with Cauldon and the Peak. Given the isolation of the grave and the rough proximity to the river one suspects some liminal figure. Perhaps a long-serving guard or ferryman of the vital crossing of the Trent near Stone, who had made his home a little north at Barlaston. The site appears to be above a small tributary of the Trent, so one might imagine him skimming his coracle a short way down the tributary to reach the main Trent. Or possibly the uncontrolled flood-plain of the Trent made the river far wider at that time, making the tributary a significant inlet, and the burial site was indeed once effectively closer to the river.

WEDGWOOD’S PAPER:

L. Wedgwood, “Notes on Celtic remains found at the Upper House, Barlaston”, Transactions of the North Staffordshire Field Club (1906)

NOTES ON CELTIC REMAINS FOUND AT THE UPPER HOUSE, BARLASTON.

BY LAWRENCE WEDGWOOD, F.R.G.S.

Read November 23rd, 1905.

We moved from Etruria to this house in 1850, and it was soon after we came, that in planting the top of the hill to the east of the house, we came upon the grave in which the bowl, sword, and knife lay.

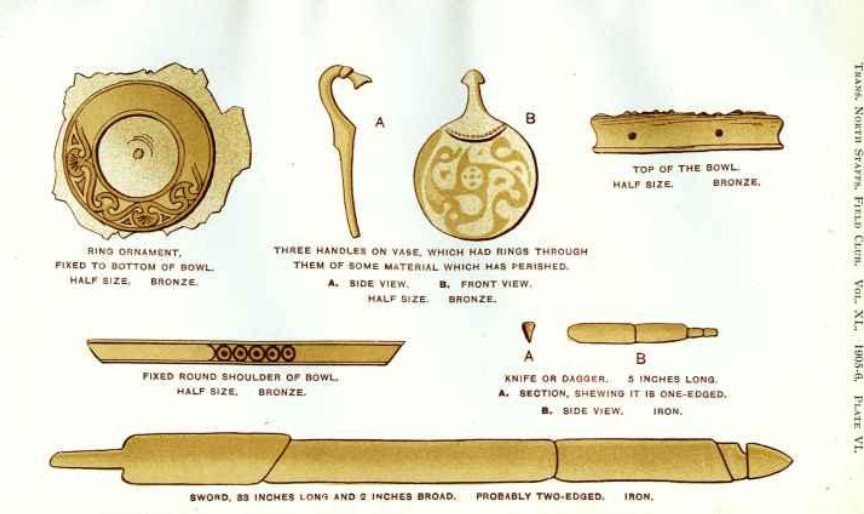

The house was built by my father on a plain grass pasture field, which had at some previous time been ploughed, and I never remember seeing any sign of a mound over the grave. One day, while the holes were being dug for planting, I found the labourers talking about some pieces of bronze they had found, and, wondering what it was, I mentioned this, and we then had the grave properly opened, and found the pieces portrayed on the accompanying sketches.

My brother, Mr. Godfrey Wedgwood, made a careful sketch of the grave and its contents, of which the sketches herewith are a correct copy.

The bronze bowl, I fear, had been shattered by the workman’s spade, but the sword lay along the side of the grave and the knife across it, the bronze bowl being, I presume, near where the head of the warrior lay (see sketch).

The sword broke into three pieces, and the knife also broke, on being lifted, being so badly rusted.

The bronze articles were in good preservation, except from the mischance of the bowl having been broken before we were aware of any grave being there. There were no bones and no cinerary [cremation] ashes, and no signs of any coffin.

Of course, being a shallow grave, and not air-tight or weatherproof, all signs of a skeleton had long since vanished.

At the date we found it, we presumed the bronze bowl to be a helmet, and the bronze handles of the bowl we thought were brooches, but other finds of recent years have led us to consider the bronze articles all part of bowl to contain the viaticum. [viaticum: heavenly meal, perhaps then understood as a sort of ‘pot of plenty’, and intended to sustain the deceased during their wandering voyage to find the halls of the afterlife]

Our grave seems to have been a solitary one, as in laying out all our garden and grounds and planting the wood to the east of the house, which would all cover five or six acres, we found no other graves, and although the top of the hill was a gravel pit when we came, and we used gravel largely from it, we found no other remains.

The hill is about 500 feet above sea level, and across the Trent, to the south-west, about two miles as the crow flies, lies the old British Camp [hill-fort] of “Bury Bank”, at the south end of Tittensor Common.

The grave is cut in the sandstone rock to some depth, and lies north and south; I presume, denoting its Pagan origin. My cousin, Mr. J. Romilly Allen, F.S.A., says the ornamentation of the bowl is distinctly late-Celtic, i.e., Pagan-Celtic of the Iron Age B.C. 300 to A.D. 450.

The form of the knife and sword, which are Saxon, however, point to a date at the end of the late-Celtic period.

The enamelled bronze discs were used as the handles of bowls, thus —

The discs were fixed to the sides of the bowls, and the hooks, which usually terminate in the head of a beast or bird, projected over the rim.

The curve of the pieces of the rim show that the diameter of the bowl was nine inches.

The curve of the ribs is the same, showing that they must have been fastened to the outside; but I don’t understand why the ends are sloping.

It looks as if they must have been placed diagonally, though how I cannot explain.

The metal is cast, not wrought, as is more usual, and the centre and marks on the bottom indicate that it must have been turned on a lathe. The enamelling of the discs and the designs arc of the Pagan-Celtic period.

The enamelling is exceptionally fine, as some of it is made, like Mille-fiore glass, by fusing several sticks of coloured glass together.

This bowl is of special value, because it is the only one that can be placed, beyond doubt, in the pre-Christian period.