Sherlock Holmes in the Midlands is a small 8” x 6” book of 125 pages, and is an excellent read. Clearly written and well researched by Paul Lester, it is logically arranged and illustrated with period illustrations, crisp contemporary photographs of sites, plus a few basic maps. Apparently it originated as a 20-page 1980s fanzine in Birmingham, but here it becomes a proper local history book. The typesetting is professional, and chapter endnotes are set in a font size that is readable without a magnifying glass. There is no final bibliography, but the bibliographic endnotes for chapters supply all the references any scholar of Holmes might require. Published in 1992, the book’s stiff covers and glue-binding have been quite adequate for 25 years, but in my copy the glue is obviously failing, with several pages almost coming loose in 2017. If a purchase of this book is being made for archival purposes, then a rebinding may be needed.

This book is best suited to those who know both Holmes and the proper1 West Midlands — the former Mercia which stretches from Herefordshire and Worcestershire and Evesham in the south, up through Birmingham and Lichfield, to the Potteries and the Peak District moorlands in the north. Almost nothing is said in the book of the East Midlands, and a casual purchaser from Nottinghamshire or Leicestershire will be sorely disappointed. I, however, was delighted by the book. Because at a great many points I was able to make a connection with places where I had grown up, where I had lived or where I now live, or places I had visited. This is due to my particular family-history, and also my childhood and workplace connections. I was especially interested in Aston and Corporation St. in Birmingham, and pleased to find that these places are extensively discussed in the book. I was even instructed on the correct pronunciation (albeit Shropshire rather than Staffordshire) of the Norman name of the place where I now live.

The book opens in the Welsh Marches, rural Shropshire, where Conan Doyle was a medical student working as an unpaid intern to a truculent local doctor. Even at that slight geographical remove from the Welsh heartlands, it appears that Conan Doyle formed there a clear prejudice regarding the Welsh tendency to nurture the sour and resentful aspects of their nature. The book then deals in a substantial manner with Doyle’s happier internship, working for a doctor in Aston, a jolly and hard-working man who welcomed the intelligent young lad into his bustling family. Aston, I should explain for the unfamiliar reader, is very near the centre of the city of Birmingham. I was delighted to learn that Doyle “saw a very deal of the very low life” in Aston between mid 1879 and February 1880, as a visiting doctor, because that meant he might have been rubbing shoulders with my ancestors in Aston. Perhaps even treating one of them, since a key female relative was plucked from poverty in Weeman Row, a slum since cleared and now roughly underneath the current Children’s Hospital at the east end of Corporation St.

Lester usefully points out possible connections of places and place names with Holmes stories, but he doesn’t labour his points. He also usefully summarises and evaluates the speculations of previous Holmes scholars, but again briefly and with a very light touch. Thus the reader learns that there was a violin seller in Sherlock Street in Birmingham city centre at the time Doyle was working there (mid 1897-February 1880, and again in early 1882), but this is not claimed as a sure-fire inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, merely suggested as one such possible example. Doyle’s keen interest in photography while in Birmingham is later mentioned in an aside, and I thought it a pity that more was not said of this. Perhaps it might have been explored in a few paragraphs added to the chapter on Doyle’s Midlands spiritualist connections and spirit photography. In that chapter I was however fascinated to read a full account of Doyle’s duping by spiritualist forgers at Crewe (a stone’s throw outside the Midlands, being a large railway town not far from the Potteries), and learned there once existed a ‘Society for the Study of Paranormal Pictures’, of which Doyle was the Hon. Sec. It seems incomprehensible today that the effective removal of the assured comforts of the Christian religion by science could have displaced the old religious sentiments in such gross directions. In Doyle’s case, into a belief in such obvious charlatanry as spiritualism, spirit photography and the idea that bottom-of-the-garden fairies could be photographed. Yet, Doyle credulously championed them all, and was often flanked by accomplished scientists such as the Potteries man Oliver Lodge.

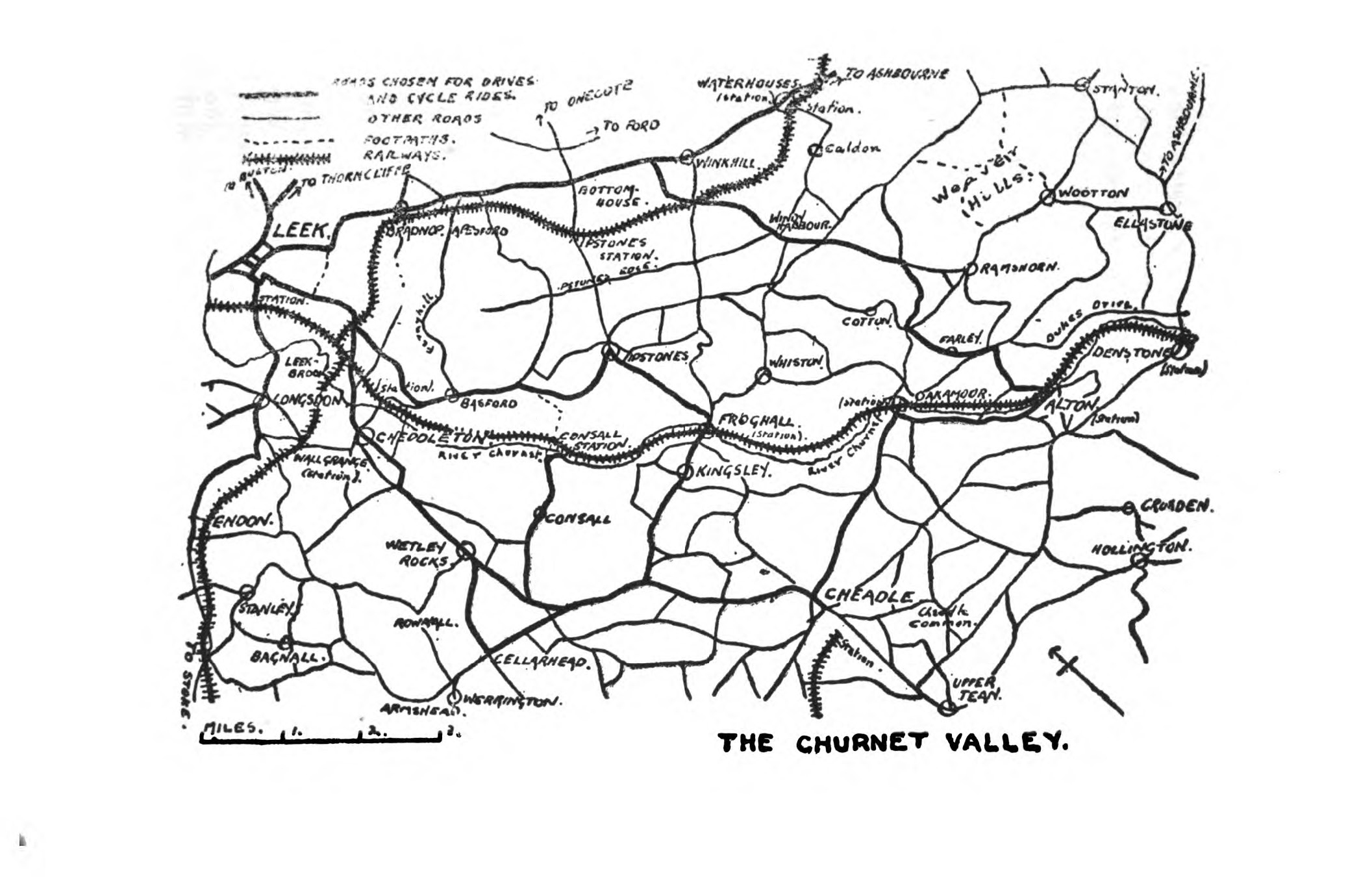

As well as tracking Sherlock Holmes through the Midlands counties of Herefordshire, Warwickshire, and up into the Peak District, some of the local non-Holmes stories are also noted. Personally I would have been inclined to add an extra chapter just to explore these stories and their settings. These are stories such as “The Doings of Raffles Haw” (set “14 miles north of Birmingham” in the wedge of mid Staffordshire country between Lichfield and Tamworth); the fine horror story “The Terror of Blue John Gap” (the Peak District, ‘Blue John’ implying Castleton); and the weird story “The Japanned Box” (near Evesham, in the far south of the Midlands). Doyle’s real-life investigation of the Great Wyrley police conviction of George Edalji is given another re-telling, with careful summation and evaluation.

Shropshire and Herefordshire are places I only know from early and middle childhood, but so far as I can tell Lester’s book is sound on all the points of local geography for the various counties. Which is not the case for the Penguin Classics notes found in a key Holmes edition — in which cloistered academics misleadingly parrot local tourism puffery that Walsall is… “in the heart of what is known as the Black Country” — when it’s at the far end of it and the “heart” is around Tipton. Sherlock Holmes never stalked the industrial districts of the Black Country or the Potteries, and so far as I know (I’ve read all the stories three times now, the last read-through being about ten years ago) there is no substantial descriptive mention of such places. Though this very absence might suggest locations for the writers of newly-minted Holmes stories, the characters now being in the public domain. Thus the Black Country cannot claim a setting used for a Holmes story, but in Lester’s book I learned that the Industrial Museum there does now have the original ‘pillar box’ (red iron post-box, into which the public could post hand-written letters and postcards) that once stood in Baker St. in London. Other fascinating snippets I learned included the insight that the local makers of umbrellas, sewing machines and watches in Birmingham and Coventry all contributed some aspect of their skills to the invention of the first modern bicycles (Doyle, like Wells, was a keen cyclist, and I have an interest in the trade due to a long line of bicycle makers in my main family-tree). It takes a while to think that one through, but it’s correct and is a fascinating spotlight on how inventions arise in dense industrial districts in which many trades mix and mingle in a free market. Before reading this book I had also not known that Samuel Johnson of Lichfield — the famous dictionary maker — had started his literary career at Old Square, just off Corporation St. in Birmingham. Thus Corporation St. can claim to have been a formative influence on Johnson was well as on Tolkien.

This is a fascinating read for those interested in its locations. It is formed from a blend of well-tested Holmes scholarship and new primary sources, polished up with much pavement-pounding at the actual locations. Sherlock Holmes in the Midlands is well worth your £3-£5 when it pops up in used form on Amazon or eBay. Might we hope for an expanded and updated ebook version, at some point in the future? Perhaps surveying the non-Holmes Midlands stories, expanding on Doyle’s interest in photography at Aston, and surveying or listing the best of the Holmes fan fiction set in the West Midlands?

1. proper West Midlands — There is also a vile 1970s bureaucratic invention calling itself the West Midlands, but which only covers a Birmingham/Coventry portion of the real West Midlands. It seems to be merely a way of grabbing taxpayer funding without having to then share it with the surrounding towns and rural areas.