New Burslem School Board buildings, 1903. New shop in Queen Street, 1909. The Town Hall at the opening of the Wedgwood Institute, spring 1869.

Author Archives: David Haden

Bidston Observatory

“June 2017 – Last year in September, we took on Bidston Observatory in order to re-establish the site as one of artistic research.”

It’s not that far away by train, on the Wirral, and may be of interest to those who connect often with Liverpool.

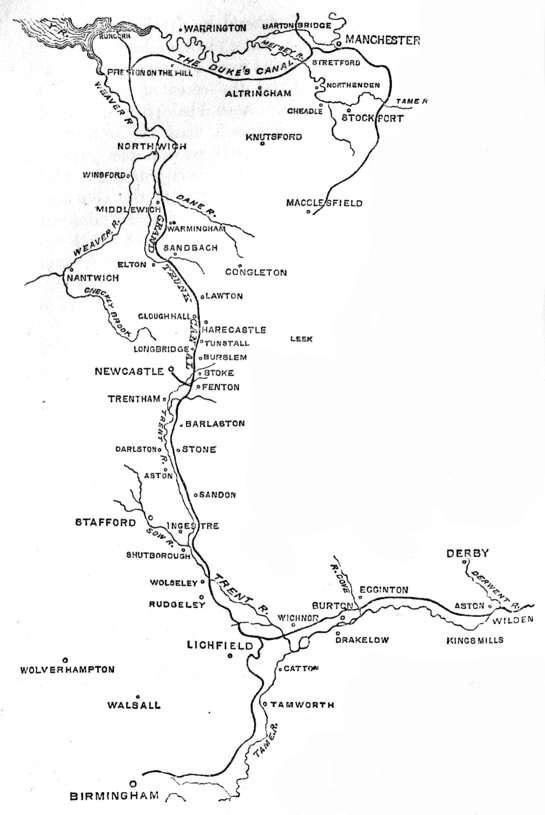

Old map of Staffordshire

Tolkien Companion, dated, priced, Kindle-d

This is looking rather tasty: the new revised and edition of the Tolkien Companion / Guide / Chronology three-volume set has been dated on Amazon UK. It’s pre-ordering now for delivery in November. Better, there’s to be a keyword-searchable Kindle edition, offering all three huge volumes for a fairly modest and piracy-busting £24.

I’ve recent acquired Tolkien’s Gedling and the two J. S. Ryan books Tolkien’s View and In the Nameless Wood, and hope to be reviewing them here soon.

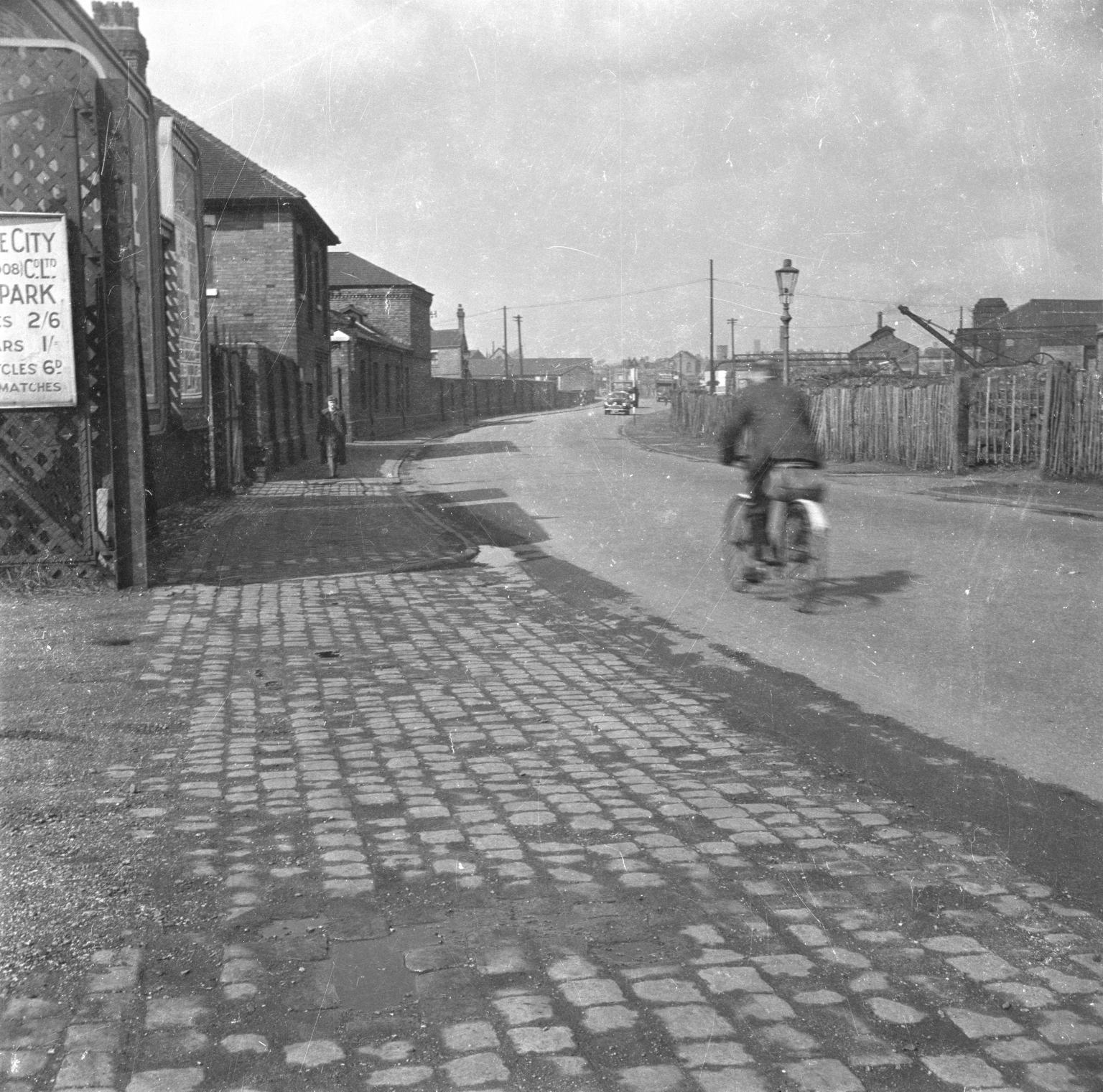

Nigel Henderson in Stoke (3) – miscellaneous pictures

Photographs by Nigel Henderson: various Stoke pictures.

As well as visiting the steel works and the Stoke City F.C. parking ground, it appears he also got on a bus and went to Cobridge for some reason, presumably to try to photograph Arnold Bennett’s home at No. 205. But he only photographed the Stag Inn at No. 114 – he was perhaps thinking that that was the pub where the young Bennett would have supped? Or was No. 205 nearby, on the side of the road on which he stood?

Two pictures (from a stopped bus?) of lads playing lunchtime football at a pot-bank.

A nice bit of pavement edging that caught his eye.

I think he probably made this picture just as an interesting composition. Looks like a water-tank building for a small works, perhaps part of an abandoned pot-bank he ventured into?

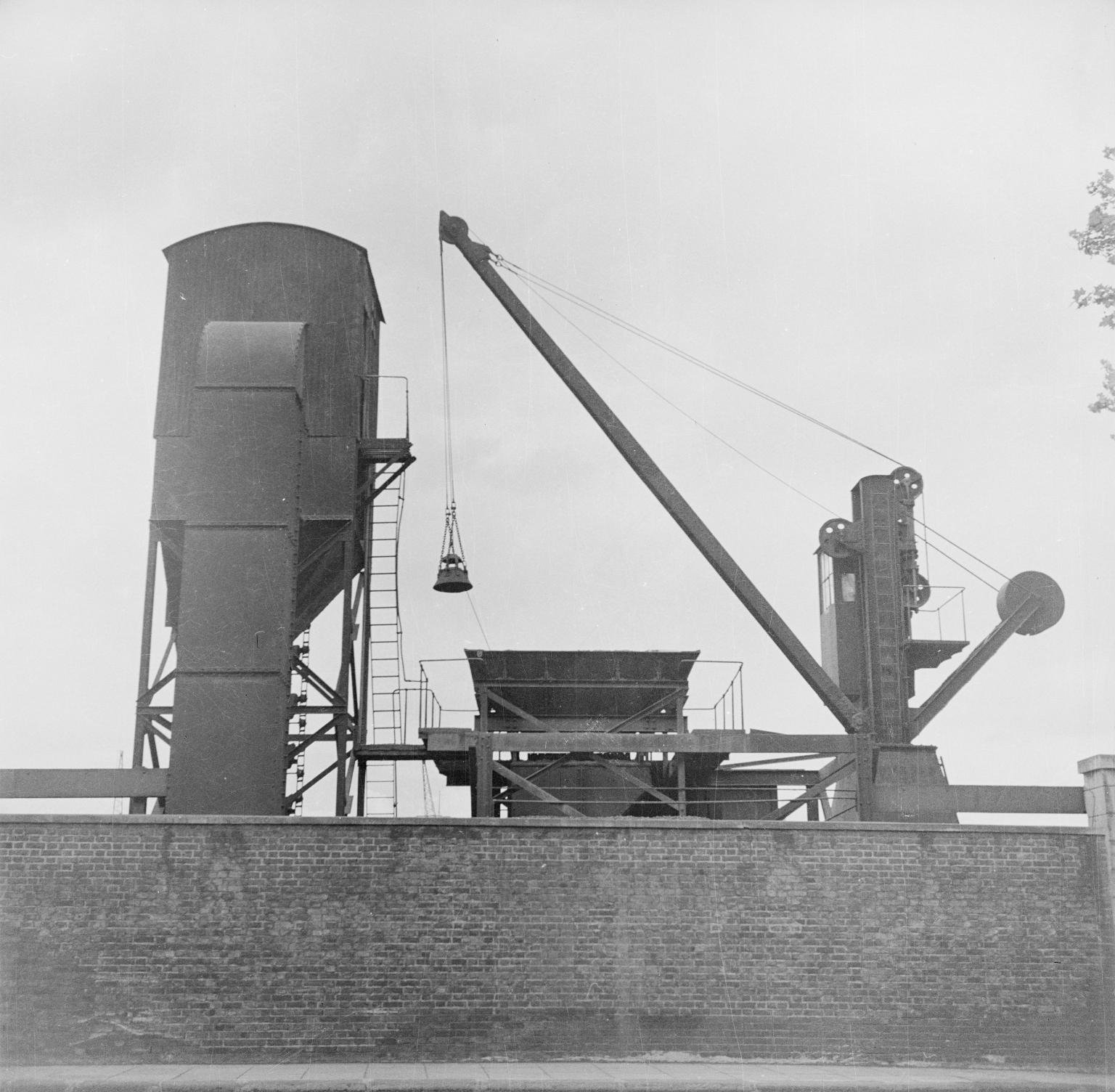

Nigel Henderson in Stoke (2) – the Boothen End parking

More photographs of Stoke by Nigel Henderson, this time of the Stoke F.C. parking grounds at Stoke on the Whieldon Road, before the A500. I’m not sure why he went there in particular. Perhaps a friend in London, who had gone to a Stoke match, told him he would get good wide views of the Boothen End stand from there? But the stand and its floodlights appear to be some way away, beyond the chain-link fence and gas-holders. Or did something of importance once stand on those parking grounds, perhaps a factory that someone in his family-tree once worked in, or their house? I’ve also tacked on a low-res Potteries.org photo (end) showing the canal directly opposite the entrance to the parking grounds. Doulton Sanitary Potteries Ltd has since been demolished. Apparently it supplied the ceramics for the movie Carry On at Your Convenience, and is credited in the film’s titles, though the movie wasn’t filmed there and I’m fairly sure didn’t even appear fleetingly in any establishing shots.

Additional context:

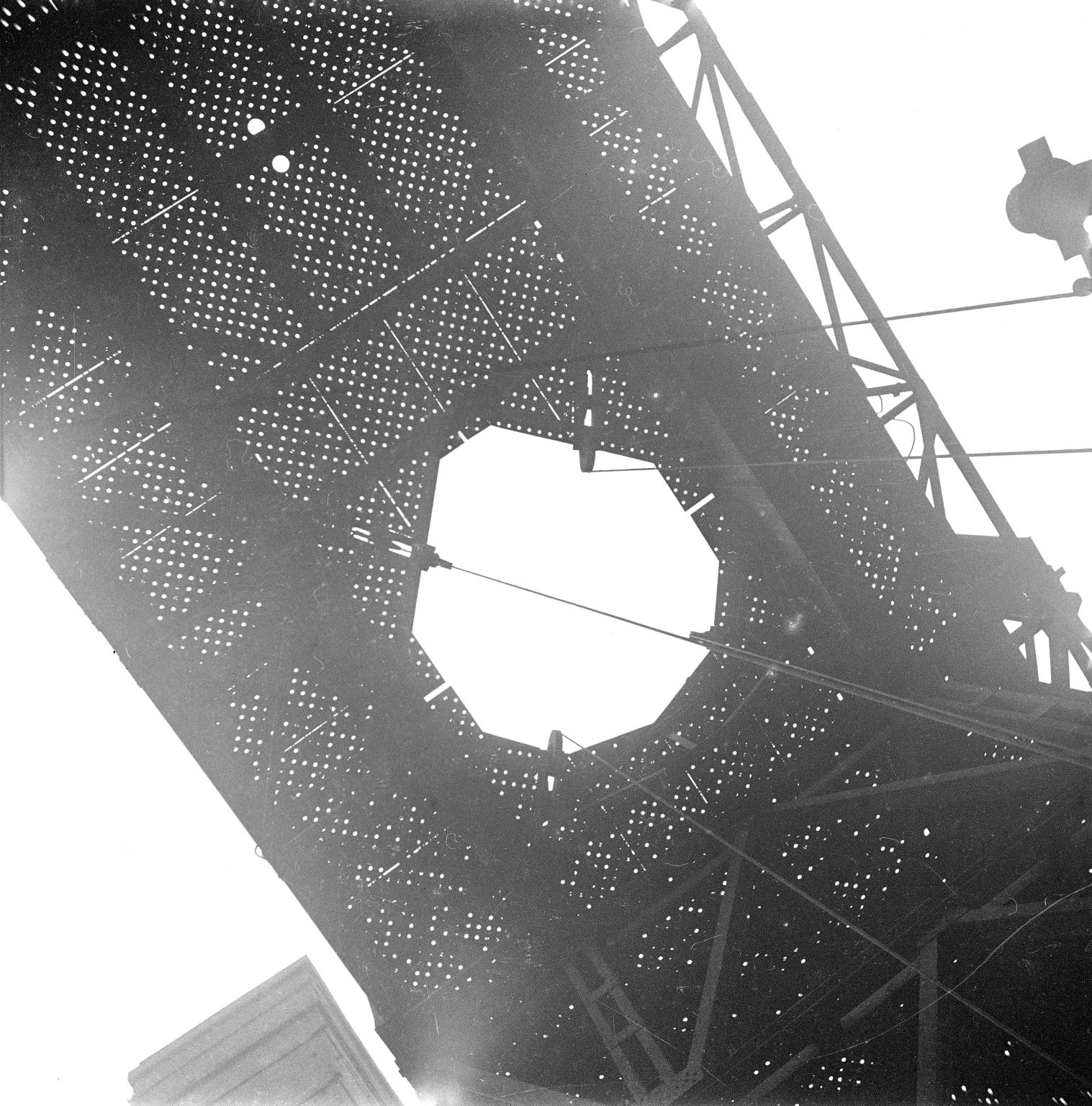

Nigel Henderson in Stoke (1) – the steelworks

Photographs by Nigel Henderson of a steel works at Stoke, which must have been Shelton. The older damaged photo of an interior with large pipes looks like his re-photographing of a Victorian or Edwardian photo, perhaps held in the works archives and brought out to show visitors on a tour. It obviously wasn’t made with the same sharp lens which he’s using for the other pictures. The same might be true of the double-exposure interior with the wheels.

Looks like he’s using a square-format Rolleiflex newspaperman’s camera.

Market Place, Burslem (newly colorised)

Drawing The Street

Drawing the Detail added to the sidebar links on this blog. Fabulous new-made architectural elevations, done in a very pleasing pen and wash style. You can also buy prints at Drawing The Street. Here’s a glimpse of the style, and also a glimpse (in the colours, at least) of what-might-have been had Burslem town centre managed to gentrify like other large market towns.

Old fossils, new ideas

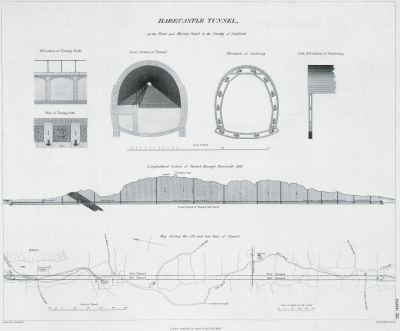

A new essay notes that the earliest theory of evolution first emerged from the Harecastle Tunnel in 1767, at the northern-most end of the Stoke valley…

“Erasmus Darwin started to think about evolutionary ideas when his curiosity was aroused by the discovery of mammoth bones at Harecastle near Kidsgrove”

I’m not sure where the author of this new essay got “mammoth” from, as that species is not specified in any source I can find. But certainly large fossil bones, including a giant fish, were found on the south side of the tunnel. According to Wedgwood…

“at the depth of five yards from the surface … in a stratum of Gravel under a bed of Clay of a very considerable thickness,”

Given that the surface has been quite cut back and down at Harecastle, by standing on the iron canal bridge there I guess one might be at the same level as a strata “five yards from the [original] surface”? The British Museum lists a giant shark-tooth from Harecastle, perhaps indicating the nature of the fish bones.

Apparently the obvious choice of the River Weaver for transport of the fossils to Darwin but not possible because, in Wedgwood’s words, on the Weaver… “the boatmen are sure to pilfer them”. Would that method have involved a packhorse to the Weaver at Crewe and then by sea from Liverpool to London and road to Lichfield? Anyway, by whatever means of transport they were sent, the “big bag” of bones arrived in Darwin’s stable-yard in Lichfield.

Darwin was a leading medical doctor of the time, but even he was rather baffled by the bag’s contents. He tentatively suggested, in a letter to Wedgwood, the likeness of a huge vertebrae bone to that of a camel. He also noted that what appeared to be a horn was more gigantic than any other horn he had heard of.

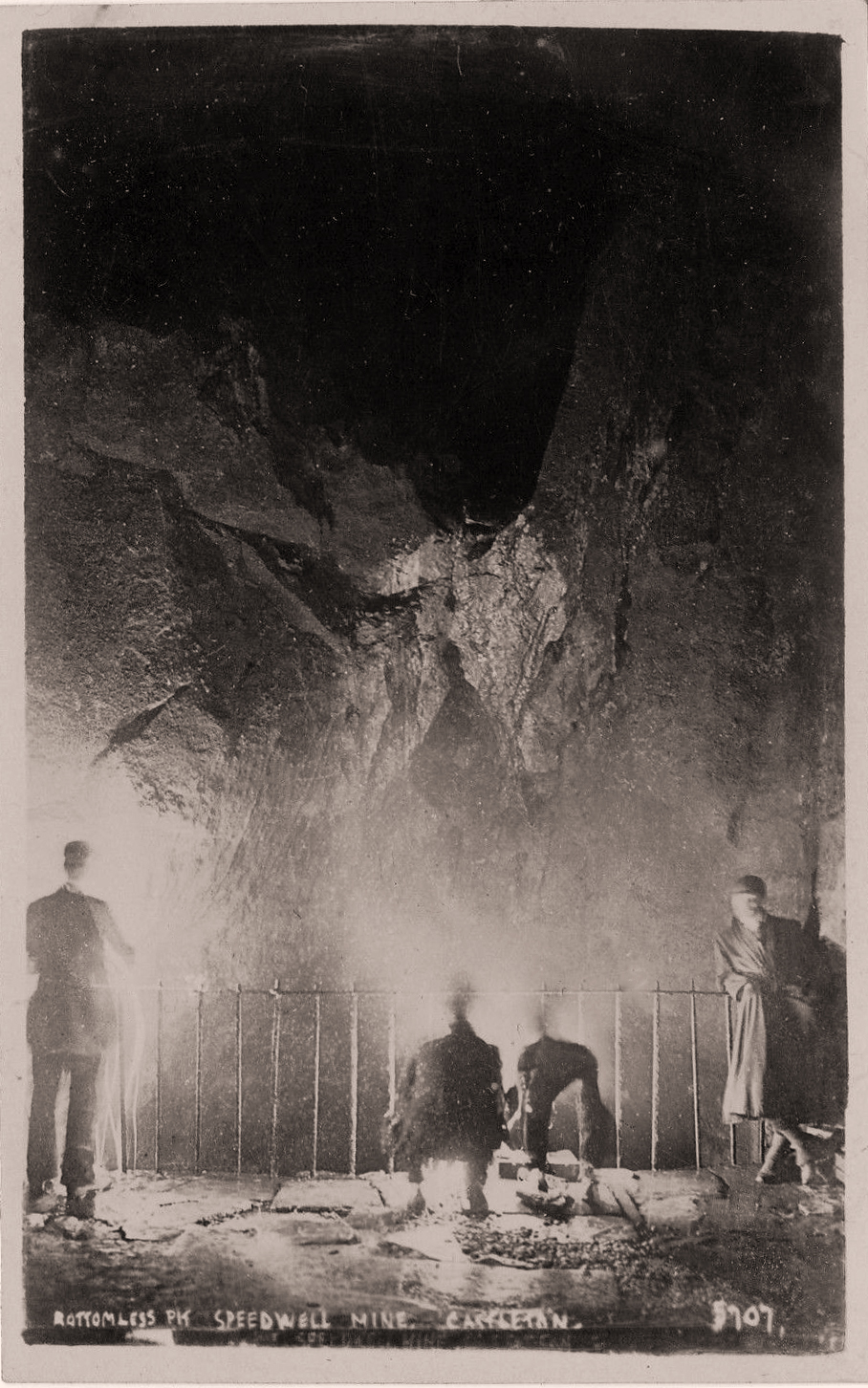

His curiosity piqued, and his pride in diagnosis perhaps just a little deflated, Darwin immediately decided he needed to gain an in situ understanding of just how rock strata were formed and how they lay. Unable to get to Harecastle from Lichfield (Wedgwood’s letter stated the journey would involve considerable cost, at that time) he took a swift two-day trip around the caves and rock strata of the Peak District, more easily accessed from Lichfield. He was in the company of Mathew Boulton of Birmingham, the geologist John Whitehurst of Derby, and Darwin’s eldest son Charles went along as assistant to his father. The men also went deep underground at Treak Cliff Cavern, a mine since Ancient Roman times as a source for ‘Blue John’.

Boulton took up this rare, but quite cheap, stone for his affordable Blue-John vases made in Birmingham. One popular TV historian has suggested that crushed ‘Blue John’ also contributed to the mix for the attractive ‘Wedgwood blue’ look in pottery, but I can find no supporting evidence for this. Yet it seems that Wedgwood did supply Boulton with jasperware plaques for Blue-John columns meant to elegantly ‘set off’ his new Blue-John vases.

Darwin somewhat jokingly proposed erecting, over the site of the gigantic fossil bones, a gigantic statue to the canal builder…

“I am determined to have the Mountain of Hare-castle cut into a Colossal Statue, bestriding the Navigation [the canal], and an inscription in honour of The Wedgewood.”

Sadly the ‘Giganticus Wedgwoodia’ statue wasn’t to be, and instead we only got an incredibly dull municipal monument at Bignall Hill. But Darwin began a far more monumental work. From the Harecastle bones, and the Peak District visit, Darwin formed a theory of ‘common descent’ — that all life must have at one time originated with a common ancestor. Most probably a shell-dwelling creature. Implied in this idea is the assumption that life diversifies in its forms, branching off into wholly new species, and that there must be some underlying driver for this process. Most pleased with his new idea, he was sure enough of its value to promptly have…

“fossil shells on his newly minted family crest, along with the motto E conchis oninia (‘everything from shells’)”.

He displayed this crest on his coach, until obliged to remove it from public display by an offended local Canon at Lichfield Cathedral. The Canon attacked him in a rhyme…

O Doctor, change thy foolish motto,

Or keep it for some lady’s grotto.

Thereafter, not wishing to be ‘cancelled’ and be deserted by his Church-going medical patients (the threatening implication of the poem), Darwin had to be content with using the crest privately and as a book-plate. But he cunningly took the Canon’s unwitting advice and method and slipped his evolutionary theories into a fine book of poetry aimed at ladies, The Botanic Garden. When that book became a runaway best-seller, a copy in every intelligent “lady’s grotto”, he felt confident enough to elaborate his 25 years of pent up ideas in the science book Zoonomia (1794-96), which had a substantial chapter on biological evolution. The new essay linked above gives an outline of this book’s key ideas. Unfortunately for Darwin the book ran smack into an unexpected cloud of national and international politics, a cloud not cleared up until after the Battle of Waterloo. It would take his grandson Charles to fully develop and prove beyond doubt the radical idea of evolution, and then others such as Huxley would ably pilot it through the hostile establishment consensus and towards a general acceptance.

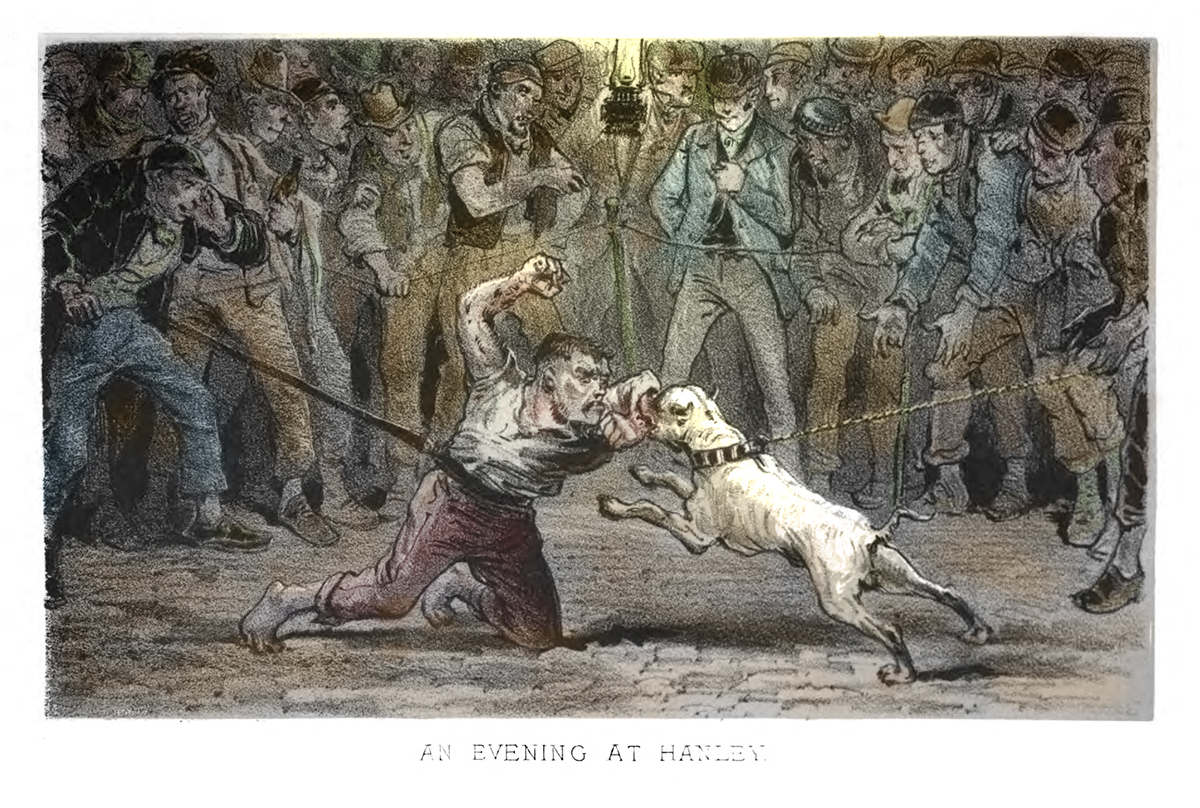

It’s bad up Hanley…

And you thought a Saturday night in Hanley was bad in 2017…

Actually it’s a dwarf-fights-dog fiction, invented and passed off as part of a supposedly factual ‘I visited Stoke and lived’ news report. The writer was an unscrupulous London journalist, later derided for inventing large chunks of his visit. Not much changes, eh?

A Chartist leader escapes from the Potteries, 1842

A Chartist leader escapes from the Potteries, 1842. From The Life of Thomas Cooper:

At dusk, I closed the [Chartist] meeting; but I saw the people did not disperse; and two pistols were fired off in the crowd. No policeman had I seen the whole day! And what had become of the soldiers I could not learn. I went back to my inn; but I began to apprehend that mischief had begun which it would not be easy to quell. […] two Chartist friends went out to hire a gig [horse carriage] to enable me to get to the Whitmore station, that I might get to Manchester: there was no railway through the Potteries, at that time. But they tried in several places, and all in vain. No one would lend a gig, for it was reported that soldiers and policemen and special constables had formed a kind of cordon round the Potteries, and were stopping up every outlet.

Midnight came, and then it was proposed that I should walk to Macclesfield, and take the coach there at seven the next morning, for Manchester. Two young men, Green and Moore, kindly agreed to accompany me; and I promised them half-a-crown each.

[He disguises himself] Miss Hall, the daughter of Mr. Hall the land-lord of the George and Dragon, lent me a hat and great-coat I put them on, and putting my travelling cap into my bag, gave the bag to one of the young men, and my cloak to the other; and, accompanied by Bevington and other friends, we started. They took me through dark streets to Upper Hanley; and then Bevington and the rest bade us farewell, and the two young men and I went on.

My friends had purposely conducted me through dark streets, and led me out of Hanley in such a way that I saw neither spark, smoke, or flame. [of the riot, and] during that night scenes were being enacted in Hanley, the possibility of which had never entered my mind, when I so earnestly urged those excited thousands to work no more till the People’s Charter became the law of the land. Now thirty years have gone over my head, I see how rash and uncalculating my conduct was. But, as I have already said, the demagogue is ever the instrument rather than the leader of the mob.

[Instruction was given to] the two young men, Green and Moore, who accompanied me, not to go through Burslem, because the special constables were reported to be in the streets, keeping watch during the night; but to go through the village of Chell, and avoid Burslem altogether.

I think we must have proceeded about a mile in our night journey when we came to a point where there were two roads; and Moore took the road to the right while Green took that to the left.

[… they argue tediously for some minutes …]

” I tell thee that I’m right,” said the one.

” I tell thee thou art wrong,” said the other.

And so the altercation went on, and they grew so angry with each other that I thought they would fight about it.

” This is an awkward fix for me,” said I, at length. “You both say you have been scores of times to Chell, and yet you cannot agree about the way. You know we have no time to lose. I cannot stand here listening to your quarrel. I must be moving some way. You cannot decide for me. So I shall decide for myself. I go this way,” — and off I dashed along the road to the left, Moore still protesting it led to Burslem, and Green contending as stoutly that it led to Chell.

They both followed me, however, and both soon recognised the entrance of the town of Burslem, and wished to go back.

” Nay,” said I, “we will not go back. You seem to know the other way so imperfectly, that, if we attempt to find it, we shall very likely get lost altogether. I suppose this is the highroad to Macclesfield, and perhaps it is only a tale about the specials [volunteer night-guards at Burslem].’

In the course of a few minutes we proved that it was no tale. We entered the market-place of Burslem, and there, in full array, with the lamp-lights shining upon them, were the Special Constables! The two young men were struck with alarm; and, without speaking a word, began to stride on, at a great pace. I called to them, in a strong whisper, not to walk fast — for I knew that would draw observation upon us. But neither of them heeded. Two persons, who seemed to be officers over the specials, now came to us. Their names, I afterwards learned, were Wood and Alcock, and they were leading manufacturers in Burslem.

” Where are you going to, sir? ” said Mr. Wood to me. “Why are you travelling at this time of the night, or morning rather. And why are those two men gone on so fast?”

“I am on the way to Macclesfield, to take the early coach for Manchester,” said I; “and those two young men have agreed to walk with me.”

” And where have you come from?” Asked Mr. Wood; and I answered, “From Hanley.”

“But why could you not remain there till the morning ?”

“I wanted to get away because there are fires and disorder in the town — at least, I was told so, for I have seen nothing of it.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Alcock had stopped the two young men.

“Who is this man?” He demanded; “and how happen you to be with him, and where is he going to?

“We don’t know who he is,” answered the young men, being unwilling to bring me into danger” he has given us half-a-crown a piece, to go with him to Macclesfield. He’s going to take the coach there for Manchester, to-morrow morning.”

” Come, come,” said Mr. Alcock, “you must tell us who he is. I am sure you know.”

The young men doggedly protested that they did not know.

“I think,” said Mr. Wood, “the gentleman had better come with us into the Legs of Man” (the principal inn, which has the arms of the Isle of Man for its sign), “and let us have some talk with him.”

So we went into the inn, and we were soon joined by a tart-looking consequential man.

“What are you, sir?” Asked this ill-tempered-looking person.

“A commercial traveller,” said I, resolving not to tell a lie, but feeling that I was not bound to tell the whole truth. And then the same person put other silly questions to me, until he alighted on the right one, ” What is your name ?”

I had no sooner told it, than I saw Mr. Alcock write something on a bit of paper, and hand it to Mr. Wood. As it passed the candle I saw what he had written, — “He is a Chartist lecturer.”

“Yes, gentlemen,” I said, instantly, “I am a Chartist lecturer; and now I will answer any question you may put to me.”

“That is very candid on your part. Mr. Cooper,” said Mr. Alcock.

” But why did you tell a lie, and say you were a commercial traveller?” – asked the tart-looking man.

“I have not told a lie,” said I; “for I am a commercial traveller, and I have been collecting accounts and taking orders for stationery that I sell, and a periodical that I publish, in Leicester.”

“Well, sir,” said Mr. Wood, “now we know who you are, we must take you before a magistrate. We shall have to rouse him from bed; but it must be done.”

Mr. Parker was a Hanley magistrate, but had taken alarm when the mob began to surround his house, before they set it on fire, and had escaped to Burslem. He had not been more than an hour in bed, when they roused him with the not very agreeable information that he must immediately examine a suspicious-seeming Chartist, who had been stopped in the street. I was led into his bedroom, as he sat in bed, with his night-cap on. He looked so terrified at the sight of me — and bade me stand farther off, and nearer the door! In spite of my dangerous circumstances I was near bursting into laughter. He put the most stupid questions to me; and at his request I turned out the contents of my carpet-bag, which I had taken from the young men, with the thought that I might be separated from them. But he could make nothing of the contents – either of my night-cap and stockings, or the letters and papers it held.

Mr. Wood at last said, “Well, Mr. Parker, you seem to make nothing out in your examination of Mr. Cooper. You have no witnesses, and no charges against him. He has told us frankly that he has been speaking in Hanley; but we have no proof that he has broken the peace. I think you had better discharge him, and let him go on his journey.”

Mr. Parker thought the same, and discharged me. His house was being burnt at Hanley while I was in his bedroom at Burslem. I was afterwards charged with sharing the vile act. But I could have put Mr. Parker himself into the witness-box to prove that I was three miles from the scene of riot, if the witnesses against me had not proved it themselves. The young men, by the wondrous Providence which watched over me, were prevented going by way of Chell. If we had not gone to Burslem, false witnesses might have procured me transportation for life [to Australia as a convict].

Were these young men true to me? Had they deserted me, and gone back to Hanley ? No: they were true to me, and were waiting in the street; and now cheerily took the bag and cloak, and we sped on again, faster. We had been detained so long, however, that by the time we reached the “Red Bull,” a well-known inn on the highroad between Burslem and the more northern towns of Macclesfield, Leek, and Congleton, one of the young men, observed by his watch that it was now too late for us to be able to reach Macclesfield in time for the early coach. The other young man agreed; and they both advised that we should strike down the road, at the next turning off to the left, and get to Crewe — where I could take the railway for Manchester. We did so; and had time for breakfast at Crewe, before the Manchester train came up, when the young men returned [to the Potteries].

A second special Providence was thus displayed in my behalf. If we had proceeded in the direction of Macclesfield, in the course of some quarter of an hour we should have met a crowd of working men, armed with sticks, coming from Leek and Congleton to join the riot in the Potteries. That I should have gone back with them, I feel certain; and then I might have been shot in the street, as the leader of the outbreak.