Penkhull historian Richard Talbot, writing in The Sentinel today, mentions the earliest medical institution in the modern Potteries district circa 1804 to 1820…

“Apart from one small Dispensary of Recovery at Etruria, there was little to support those who were ill with mass-killers of the day: smallpox, cholera, typhoid and typhus were left to their own devices.”

“Small”? But the Victoria County History records that that the ‘House of Recovery’, far from being “small” or only a dispensary, was three stories high…

“The ‘House of Recovery’ for the poor, consisting of a dispensary and a reception ward and supported by voluntary contributions, was built in 1803–4 at Etruria Vale, north of the Bedford Street canal bridge; of brick and three stories high”.

Even this was soon replaced by something even larger. The article “Dispensary and House of Recovery: The first public hospital in North Staffordshire” states that in 1819 it was realised that…

“larger buildings were required and the site was not suitable for expansion. A new infirmary was erected in Etruria [and that] operated until 1869”.

There may have been in the 1810s, as Talbot claims, “little to support those who were ill with mass-killers of the day: smallpox”, simply because little could be done by science once the disease took hold of an individual. But Talbot’s article omits something. Since the “Dispensary and House of Recovery” article also comments that at Etruria…

“Good work on the prevention of illness progressed with a program of vaccination against smallpox (developed by Edward Jenner in 1796-8) and encouragement to factory and mine owners to improve safety.”

So, Etruria was not “small” by the standards of the time, and nor it seems were its doctors indifferent to smallpox in terms of its mass prevention in the district. Indeed, as early as 1792 the Reverend William Turner of Newcastle had issued a booklet entitled “An Address to Parents on the Subject of Inoculation for the Small-Pox”, in favour of pre-Cowpox vaccination, and…

“Thomas Wedgwood (a son of Josiah Wedgwood I) had evidently expressed interest in the subject, for he took 1,000 copies for distribution round Etruria” (The Reverend William Turner, 1997)

Evidently then at least one large manufacturing family personally engaged in the struggle against smallpox, alongside the doctors. Indeed, the Wedgwood family led by example, and had long been vaccinating their own children.

By the early 1860s smallpox had all but gone as a regular epidemic…

“Smallpox is occasionally met with in the Potteries, but of late years has not been a prevailing epidemic. Vaccination is carried on pretty effectively in the Potteries.” (Clinical Lecturers on The Diseases of Women, 1864)

There appears to have been a virulent outbreak in Longton in 1871, with 27 deaths, but vaccination proved its worth and it was contained. The authorities reported that “the disease has not spread to other towns” in the district. A national epidemic of 1902-03 did reach the Potteries in 1903, when newspapers reported that it led to a surge among the still un-vaccinated…

“So great has been the rush to be vaccinated during the present severe outbreak of smallpox in the Staffordshire Potteries that the police have been called to keep order outside the public vaccinator’s surgery.”

… but although it led to panic, the disease appears to have been late arriving from its then-stronghold of Walsall. Despite being initially “severe”, it appears to have quickly burned-out on our heavily vaccinated population — judging by medical reports in late April 1903 stating that there were few cases to be found in North Staffordshire.

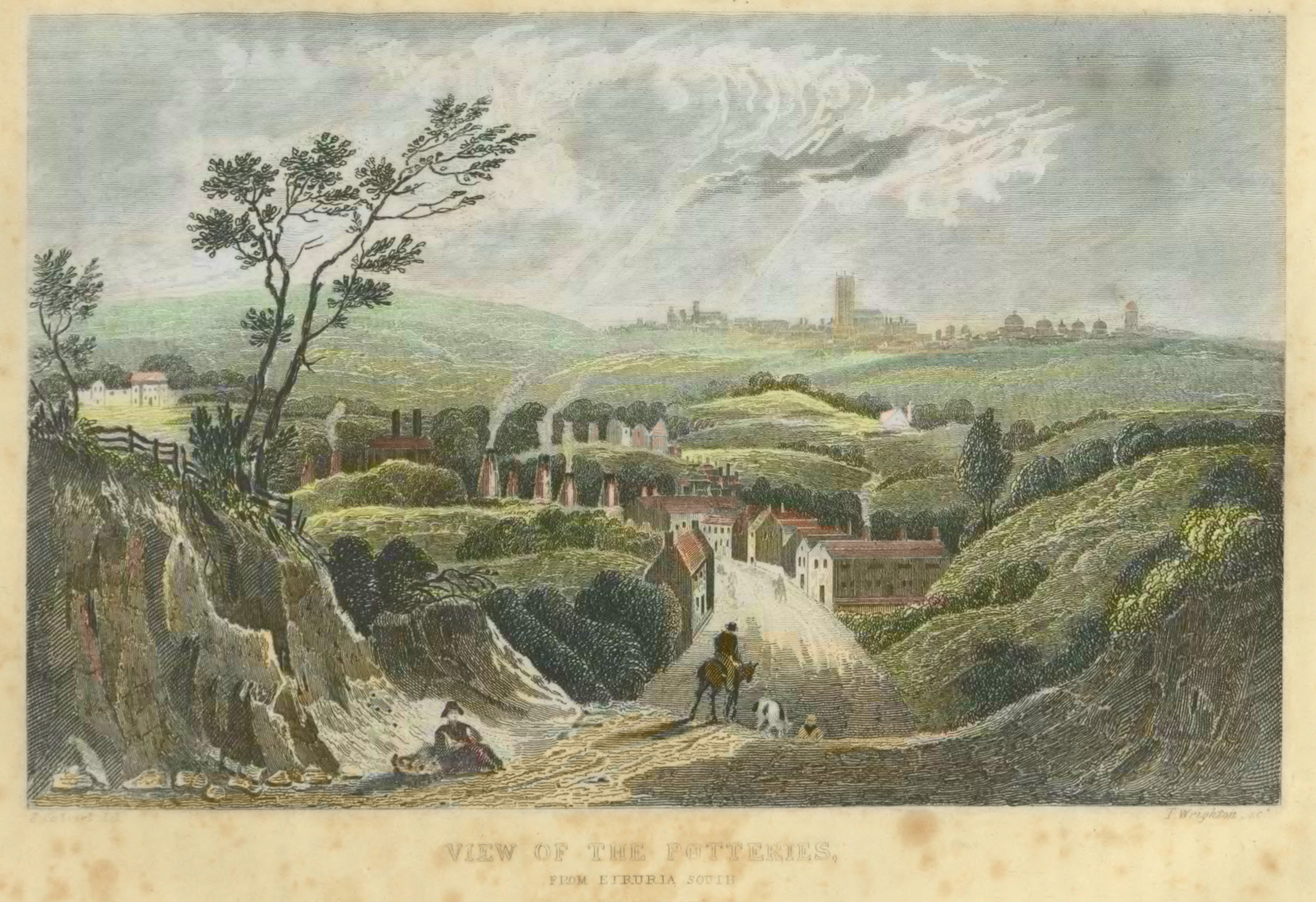

Talbot’s Sentinel article also makes one especially sweepingly claim that “Little of nature’s green was visible” in the Potteries of the early 1800s and onwards. Yet this appears to be amply disproved by the paintings and sketches of the Etruria part of the valley of around that time, as well as by first-hand accounts. For instance, here we see Etruria from the Basford Bank in 1830…

And here is another of Etruria from Basford Bank, by Henry Lark Pratt (1805-1873), perhaps two decades later. With Hanley in the distance, and Cliffe Vale to the right with upper Shelton beyond it…

This claim is also disproved more widely in the valley by even a brief study of early maps, and then later by early aerial photography made of the entire district. For instance, even in the 1920s one can see large cornfields in harvest next to Etruria Station (the Basford Bank road runs across the top of the picture), with a tile works nestled in amongst them…

We have long been a district that has mixed the rural and the industrial, side by side. Many writers including Bennett recognised this. Occasionally smoky, yes, when the pot-banks were ‘in smoke’. Often despoiled by industrial manufacturing sites and their spoil tips. But not the utterly desolated wasteland of urban myth.