New on Archive.org to borrow, the book Forgotten folk tales of the English counties (1970). Late tales gathered by a proper folklorist, with a few of relatively local interest from Cheshire/Shropshire and the west of the Derbyshire Peak. The most interesting of which is “The Asrai” (Cheshire/Shropshire, large mere pools) with supporting evidence from other sources.

Monthly Archives: January 2023

Tolkien Gleanings #30

* In the new issue of the scholarly journal 1611, a new Spanish-language article on the reception of Tolkien’s works in Spanish translation. …

“this study constitutes a contribution to the still-scarce academic bibliography on the reception of a British author, one who has come to occupy an important place in the Spanish-speaking publishing world.”

* The Chairman in Humanities at Houston Christian University has a glowing review of the new book Tolkien Dogmatics by Austin M. Freeman…

Austin Freeman has given a gift to Tolkien scholars and aficionados alike in a work I didn’t think could be written. Tolkien Dogmatics: Theology Through Mythology with the Maker of Middle-Earth painstakingly assembles, collates, and cross-references Tolkien’s legendarium, academic essays, and letters to construct a systematic theology. Though informed by the copious secondary material on Tolkien, Freeman’s work is firmly and faithfully grounded in the depth and breadth of the primary material. Broken into 12 chapters that explicate Tolkien’s views on God, revelation, creation, humanity, angels, the fall, evil and sin, Satan and demons, Christ and salvation, the church, the Christian life, and last things, Tolkien Dogmatics takes a deep dive into the theological convictions that grounded, inspired, and guided the maker of Middle-earth. In his aptly titled “Prolegomena,” Freeman makes clear his goal: “To set out as accurately as possible what Tolkien thought, without letting my or other people’s views intrude upon the matter”. He stays true to his promise.

* The Index of Medieval Art Database will become ‘free to use’ from 1st July 2023 onward. The largest online database of such research, it is well-established and includes a huge “photographic archive” with cross-reference links to the relevant texts which the pictures illustrate or allude to. The service currently requires a university subscription.

* “Hill Is a Hasty Word” is a new blog post from the English West Midlands. It helped me make the link between Treebeard’s approach to things and ‘Tolkien as a walker’. It appears that Tolkien was an ‘artist-rambler’ type of walker — relatively slow in walking and curious about his surroundings, stopping frequently to collect his thoughts and/or to consider the things he encountered big or small. Whereas Lewis appears to have been an ‘exercise-hiker’ of the brisk 1930s type — wanting to walk fast to ‘cover the ground’ and get to the destination. A slow “Cretaceous Perambulator” Lewis was not, though apparently that was how he liked to style himself as a walker. Another earlier blog post from 2019 looked at this topic of walking and has taken the time to find various quotes. Lewis said (1947, Malvern) that Tolkien was…

“not our sort of walker. He doesn’t seem able to talk and walk at the same time. He dawdles and then stops completely when he has something interesting to say”.

In 2022 First Things had another post on the topic, but with a contradictory quote (c. early 1950s, published 1955) from Lewis…

“Walking and talking are two very great pleasures, but it is a mistake to combine them.”

So, what is one to make of that? Perhaps Tolkien changed Lewis’s mind on the combination of talking and walking, between 1947 and the early 1950s, as he did with other things? Well, I’ll leave that one for the Lewis scholars to puzzle over. Another 2022 article “Walking with Chesterton and Lewis (and Tolkien)” also mused on this topic, and related the walking styles back to the writing styles…

“The Lewis brothers liked to walk vigorously, covering lots of ground; Tolkien preferred to amble, stopping every few hundred yards to look at a flower or a tree. The brothers became increasingly frustrated with their lack of progress and increasingly impatient with Tolkien’s dilatory perambulations. They strode off ahead, leaving Tolkien and Sayer to meet them in the pub when they eventually arrived. […] This difference in approach to a country walk is evident in the difference between the respective writing styles”.

* And finally, take a walk in the rich fields of Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1895) in its 1905 printing. This was the standard edition until the major revision of 1952, and thus the one available to Tolkien prior to the creation of The Lord of the Rings. This online version has very poor OCR (see the .ePub file), but is a good scan otherwise.

More Potteries ‘news you can use’

The Potteries Post has updated, with more news you can use. The site replaces my former Facebook groups ‘Creative Stoke’, ‘Wild Stoke’ etc.

Pickling and tinkering

An excellent short post about “The Britishness of British Faeries”. Despite its click-baity title that article doesn’t sum up the characteristics of Britishness and then tally them with fairy-lore and fairy-traits. Though that might make for an interesting future post at the venerable British Fairies blog.

The article is actually about how the idea of ‘fairy’ can be brought before the more rational mind. In this case by situating the fairies as the ineffable genii loci of a place, especially in the British context of our ‘deep time’ landscape and places. No diminutive Tinkerbell or neo-pagan confabulation is then required to get the basic idea across to the musing young walker.

The concise article sums this up very well. But I’d like to add a few points, around the idea that its not all about an ‘immediate emotional response’ to a place.

At worst that sort of response can simply stop short, easily slipping into a purely nostalgic and preservationist view of a place. The preservationist ends up ‘pickling the fairies’ of a place, as if in a jar of pickling vinegar.

The ‘immediate emotional response’ assumption can also overlook the contributions made by the rational thinking mind, in terms of ‘landscape place-making’ (from path-makers to tree tenders to grand folly-makers to wall-builders), and also ‘landscape place-discovering’ (folklorists and antiquarians through to modern metal-detectorists, from child den-makers to footpath naturalists). It’s not just about cultivating a hazy awareness that some distant ancestors may have once ‘dwelt’ here long ago, but rather that an active chain of creators helped to subtly shape and ‘make’ this place while respecting all the past contributions. In which case today’s beholder of the place could become a part of that chain, one of the many local stewards and makers whose work of centuries eventually enables one to say…

“Whether they’ve made the land, or the land’s made them, it’s hard to say” (Samwise Gamgee)

Although cultivating such an awareness would then risk opening the place up to unwanted ‘tinkering and improvements’, of the sort which may do more harm than good. Rather than ‘pickling the fairies’, in this case it would be ‘suffocating the fairies’ in a cloud of cringe-inducing naffness. I’m thinking here of hasty bits of ‘improvement’ of a place. Such as:

* a massive shiny new DIY shed which instantly destroys the lovely ambience on the corner of an allotments;

* some old rain-bedraggled ‘yarn-bombing’ or ‘inspirational’ message left to rot in a depressing manner;

* various quick-fix local council ‘improvements’, at best new ‘interpretation boards’ and/or a mundane municipal sculpture, at worst things like the replacement of a park’s proper wooden-slat benches with one tiny and freezing anti-dosser metal-mesh seat;

* the numerous examples of over-interpretation and political ‘interventions’ at National Trust sites, and increasingly also at nature reserves;

* ersatz ‘fairy-fication’ via sculptures — ranging from some quite acceptable bits of outdoors art sympathetically made by local people, through a host of bland wickerwork dragonflies made by fly-by-night ‘creative practitioners’, right down to the occasional naff garden-gnome gardening (sometimes not without an eccentric charm, admittedly).

Doubtless readers can think of some tinkering or ‘improvements’ done at their own favourite places, which has caused the genuine fairy-feeling to vanish while (curiously) the litter remains un-picked.

So, yes… perhaps after all it’s best to leave most people with their brief ‘immediate emotional response’, before ushering them back to their latest forgettable TV series. Rather than pushing the mood on further, into a response that risks being either about ‘pickling’ or ‘tinkering’.

Tolkien Gleanings #29

* “Song Lyrics in The Hobbit: What They Tell Us”, a 2022 undergraduate dissertation by a mature student, for the University of Southern Mississippi in the USA. Open access and public.

* News of a forthcoming book, via a slightly-expired call for papers. Titled Tolkien as a translator: investigations on Tolkien translation studies, and at a guess probably pencilled-in for 2024. The topic is…

“Tolkien as a great translator [who deserves] a collection of essays on his way of translating, the criteria he used, the choices that distinguished his style and that inevitably influenced his sub-creation(s), and the author’s thoughts on translation itself.”

* Since I’m no longer listening to the BBC, it’s taken me a while to twig to the existence of their recent Open Country podcast. This ‘audio countryside ramble’ took a November 2022 open-air walk in the Cotswolds, with Tolkien scholar… “John Garth to find traces of Tolkien Land at Faringdon Folly and the Rollright Stones”. The .MP3 is available at Listen Notes…

The tower is debatable. Probably Tolkien’s initial Oxford audience for the famous Beowulf lecture would have recognised the similarity, but in Worlds Garth wants a poster of it to be the inspiration for the hill of Hobbiton. I wasn’t convinced. Yet evidence for the ancient Rollright Stones is clear, for instance when in 1948 Tolkien berated his publisher on the topic of the Farmer Giles of Ham illustrations…

The incident of the dog and dragon occurs near Rollright, by the way, and though that is not plainly stated at least it clearly takes place in Oxfordshire. [As currently illustrated] The dragon is absurd. Ridiculously coy, and quite incapable of performing any of the tasks laid on him by the author.”

* And finally, according to the Pipedia, there has yet to be even a “list of literature where the pipe plays a major role in character and/or plot development”, let alone a book survey of such. That’s an opportunity for someone, though Middle-earth is already well-served by the new third edition of Pipe Smoking in Middle Earth (2022). Tolkien himself used a standard Dunhill briar pipe, of the sort common in the trenches at the time of the First World War — partly due to Mr. Dunhill sending them out to front-line soldiers and officers. The type of pipe-bowl also causes some aficionados of pipe-weed to call it a ‘pot’ or ‘billiard’ type of pipe, which I have to assume is correct. Sadly Tolkien did not sport a long Gandalf-ian ‘Churchwarden’ type of pipe. His favoured tobacco came in tins of Capstan Navy Cut ‘Blue’ flake pipe-tobacco, apparently a smooth and creamy Virginia blend today referred to as ‘Capstan Navy Cut Ready Rubbed’.

Tolkien Gleanings #28

* Newly and freely online in 2022, the 2014 Australian PhD thesis Imagined worlds: the role of dreams, space and the supernatural in the evolution of Victorian fantasy. The new…

“concept of hyperspace was a fundamental and sustained aspect of the British imagination” [and its deep and serious exploration then contributed to fantasy’s acceptance as] “an appropriate vehicle through which to explore the possibilities and conditions of other worlds”.

As in his medievalism, Tolkien’s thinking on time and dreams must have been entangled with this stream of culture. We have to remember that Victorian ‘reconstructed’ medievalism and proto-fantasy had a profound effect on many of Tolkien’s teachers, and later on various Edwardian youngsters (such as himself) who re-discovered it. There was also a later vogue for the old heroic romances among the more romantic soldiers who fought in the First World War, and I would imagine that some of the scientific romances (e.g. the early Wells) also had a re-reading at that time.

* In the Mail this week, a short article on a frosty walk in the Cotswold uplands. The writer goes “Following in the footsteps of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien”…

“It was the winter of 1945. They’d travelled with a group of friends from Oxford, where both were dons, to have a ‘Victory Dinner’ at The Bull Inn in Fairford to mark the end of the Second World War, and spend a few days on their passions: beer and talking.”

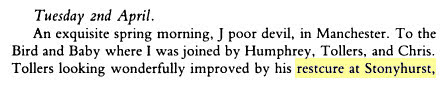

Also walking, pre-Christmas 1945. The backdrop to this was war-time food rationing and overwork and exhaustion by the war’s end. Tolkien’s health and home-life were both affected and imminent for Tolkien, when at Fairford, was a doctor-ordered “restcure”. The Chronology has “after Christmas his health gives way”. But by the following 2nd April 1946 a friend noted of him… “Tollers [Tolkien] looking wonderfully improved by his restcure at Stonyhurst” (from The Diaries of Major Warren Hamilton Lewis, 1982).

This comment adds a bit more to the ongoing mini-saga of Stonyhurst, recently mentioned several times in Tolkien Gleanings. Tolkien “stayed at a guest house in the grounds” and the guest-register shows him there “21st March to 1st April 1946”, which helps confirm the above diary entry about the “restcure” he took there. It’s strange, how seemingly unconnected bits of news can link up like that. So it can now be seen that it wasn’t just any old short break with his son at Stonyhurst. Rather it was a vital attempt at recovering his health and equilibrium, at a very difficult time both personally, creatively and nationally.

* In 2020 Christopher Armitage remembered how J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis influenced his 53-year academic career”. In the early 1950s Tolkien’s…

“lectures were always full of students [despite his being hard to hear if one was sat on the back-row. He was approachable…] Class had ended after discussing the medieval romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. “There is a refrain in that poem when characters say ‘barlay may’” Armitage said. “It’s from French, ‘parlez moi’ anglicized, and used when you’re calling for a power play or a comment. So the action is suspended.” He told Tolkien that he and childhood friends used the expression ‘barley me‘ to ask for a time-out while playing soccer or cricket in their neighbourhood street. “Tolkien was quite fascinated and asked where we played games, and I explained to him it was where I grew up in Sale, Cheshire [now south Manchester], the county south of Lancashire” Armitage said. Jotting the expression in a notebook, Tolkien insisted that Armitage provide the street address. Armitage does not know if Tolkien used the reference in a scholarly work.

Yes, I see the old dialect books confirm ‘barley me’ as a Cheshire saying. This must then be a relative of the Birmingham ‘bagsy me’. The first child who thinks to make such a bagsy statement effectively suspends any tedious and play-delaying squabble, by claiming the right to ‘go first’ in a game. Or to be the first to try a new toy, be first in the bath, to get the front rather than rear seat in a car, or get the first sausage out of the pan, etc. It might also excuse one from starting a game as IT, as in “bagsy not IT” just before a playground game of tag.

Armitage’s reminiscence also shows that in the early 1950s Tolkien was still conveying the idea of Gawain being ‘of Lancashire’ rather than (as we now know) further south in North Staffordshire. Even though Mabel Day, who Tolkien knew at this time via his involvement with the Early English Text Society and her editing of Sir Israel Gollancz’s Gawain, had in 1940 publicly and prominently suggested Wetton Mill in North Staffordshire. Day had followed Serjeantson’s 1927 suggestion of “the western part of Derbyshire” (adjacent North Staffordshire) as the home of the Gawain-poet, and Bertram Colgrave’s 1938 suggestion of North Staffordshire as a location for Gawain’s Green Chapel.

* And finally, ticket booking for The Tolkien Society’s Oxonmoot 2023 is now open, with an Early Bird discount available into February.

Tolkien Gleanings #27

* The table-of-contents for the journal Tolkien Studies #19 (2022 issue, delayed) has now been announced. I still can’t afford to get the 2021 issue yet, but of special interest to me for 2022 will be…

— “Tolkien, the Medieval Robin Hood, and the Matter of the Greenwood”.

— “Early Drafts and Carbon Copies: Composing and Editing “Smith of Wootton Major””.

— John Garth reviewing The Nature of Middle-earth.

— The “Year’s Work in Tolkien Studies 2019”, and the “2020 Bibliography”.

* I see the 2009 book Chesterton and Tolkien as Theologians has been translated into what might be Spanish. I wasn’t aware of either version before encountering the news of the new translation. It appears that the author looks for the influence of Aquinas on both men, and thus the book is partly about a probable influence on the young Tolkien.

* This week the Reading and Readers podcast reviews Austin M. Freeman’s new book Theology through Mythology with the Maker of Middle-earth.

* At the start of December 2022 the Athrabeth podcast released Episode 53: Interview with Dr. Sarah Schaefer and Dr. William Fliss, co-curators of the 2022 “J.R.R. Tolkien: The Art of the Manuscript” exhibition in the U.S.A.

* And finally, the first fan-edits have appeared for That Recent TV Series. This has been radically trimmed and re-cut to make two coherent movies, The Light of the Eldar, and The Three Rings. Apparently the cuts remove a lot of the stock ‘TV soap-opera emotion-wrenching’ and superfluous filler scenes, much violence and gore, and also what are said to be the great many over-the-top whizz-bang CGI action-scenes. In general it sounds like a quieter and less padded version, cut from 9½ to 4½ hours in total. Doubtless there will be other fan-edits in due course.

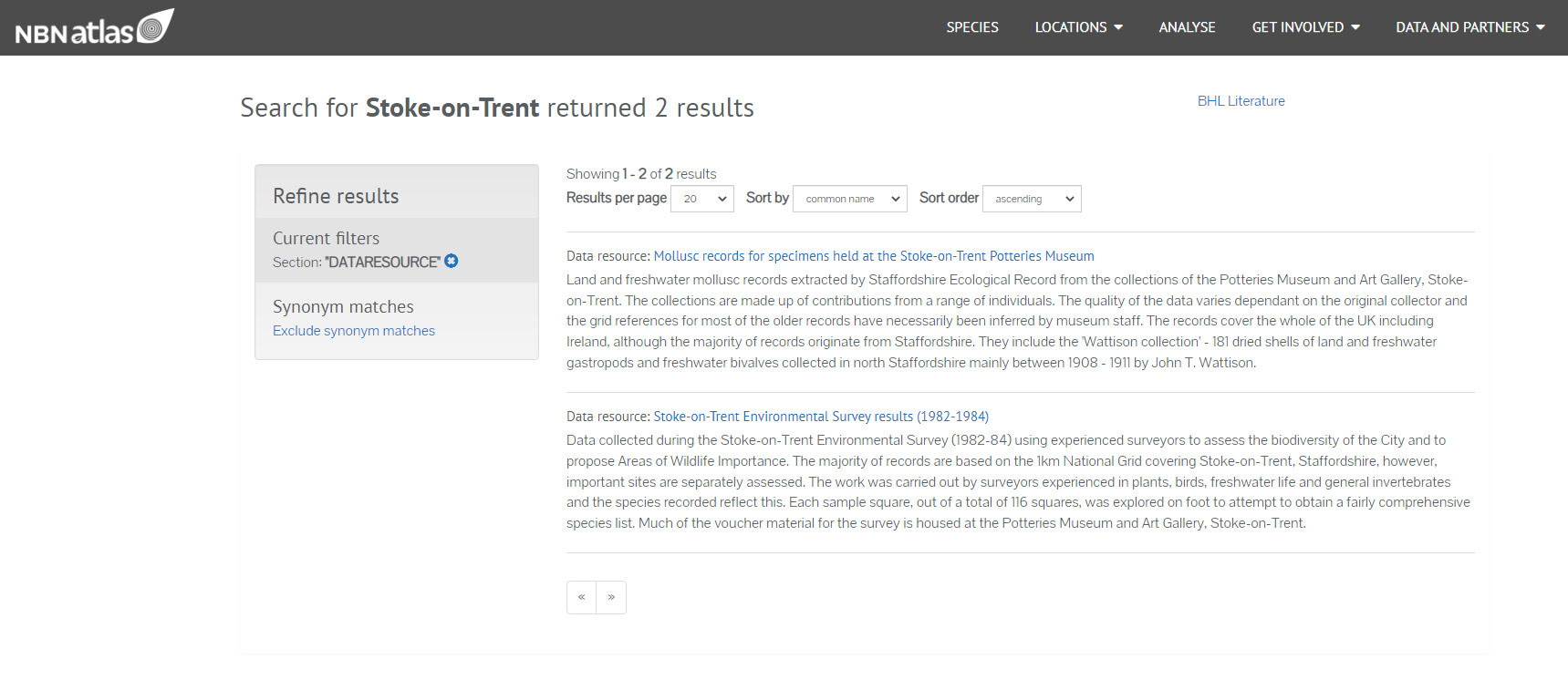

Molluscs

Stoke-on-Trent in the National Biodiversity Network Atlas.

Two items. Ecology last surveyed in the early 1980s, under the work-experience schemes of the time (so I’m told). The Museum has records of molluscs. Nothing else to see here. Move along now…

Tolkien Gleanings #26

* At Signum University, starting 1st May 2023, a live online course on “Tolkien Illustrated: Picturing the Legendarium”. Likely to be fully booked in ‘a bang and a flash’, so book early.

It’s also good to see that a live course, currently in development at Signum, is “Tolkien & Science, with Dr. Kristine Larsen”.

* Nominations are now open for the Mythopoeic Awards 2023. This is for recent new non-fiction books in ‘Myth and Fantasy Studies’ and ‘Inklings Studies’ (including Tolkien).

* “Religion along the Tolkienian Fantasy Tradition”, a panel session planned for the big International Congress on Medieval Studies, to be held in the USA in 2023. The word used is definitely “along” rather than “among”, so at a guess it’s perhaps looking at the neo-medieval religious movements and shifts that ran alongside and interacted with the post-1967 growth of the wider “Tolkienian Fantasy Tradition”? Sadly the call-for-papers is now “404”, wasn’t well distributed, and the Wayback Machine didn’t keep a copy of it.

* In the week’s Somerset County Gazette local newspaper “Queen’s College, Taunton, discovers links to J.R.R. Tolkien”…

Tolkien’s grandfather, John Suffield (1833-1930) was a pupil at the original Queen’s College when he started studying at the school September 1845, aged just 12. The school was then situated within the grounds of Taunton Castle. [He] studied at the school until he went to work in the family business. […] They also discovered that Tolkien himself was good friends with Christopher Wiseman, the headmaster of Queen’s between 1926-1953 after the pair met at King Edward’s School in Birmingham in 1905. Tolkien, Wiseman and others formed the semi-secret T.C.B.S social club centred on their mutual intellectual interests. Wiseman and Tolkien were so close at school that they called themselves the Great Twin Brethren. Of Tolkien’s close friends from the club, Wiseman was the only one to survive the First World War.

* And finally, a cosmic event on 23rd January 2023. Clouds permitting, shortly after sunset the crescent moon will rest next to the bright Venus. See Kristine Larsen’s 2021 paper for the Journal of Tolkien Research, for a special focus on this “occultation” (as it is called) of the Moon and Venus.

Above: a gold stater coin of the Iceni tribe, c. 40-50 BC. Icini territory was one of the first tribal territories that the Anglians would move through, before their settler-families moved west along the River Trent and into relatively unpopulated mid and north Staffordshire (as it would later become). Which then became the initial heartland of early Mercia on the upper reaches of the Trent.

Tolkien Gleanings #25

* A 2021 interview in English with Italian scholar Claudio A. Testi, on “Tolkien on War and Intelligence”. ‘Intelligence’ is used here in the wartime sense of ‘information likely to be advantageous in war’. Tolkien was a battlefield signals expert, and later involved in combating the Zeppelin menace. As such he was on the receiving end of intelligence activity, such as it was in the First World War. Testi’s interview observes that the over-reliance on intelligence in war can be un-wise, as shown by The Lord of the Rings. Such as the…

“… Palantir’s use, these mysterious stones that allow seeing almost everywhere. Saruman and Denethor use them, see Sauron’s army, and mistakenly lose hope. Sauron himself uses it, sees the face of a hobbit (Pippin), and mistakenly believes that the Ring is going to Minas Tirith, towards which he concentrates the greatest war effort, and so on.” […] In my opinion, The Lord of the Rings warns of the danger of transforming intelligence from a means to an end in itself. Today, with big data, this risk looks real. […] Tolkien tells us that when [such] power is too great, it becomes too dangerous.” [It] “cannot be governed, but it governs us”. […] The true leader is not the one who has the most information but the one who is most aware of the dangers of power” and especially the danger of mass intelligence gathering in terms of its potential to mislead. There is also the further and wider danger in the Ring, that having “utmost intelligence completely destroys freedom” among people, or it would if used by one who knew how to wield it.

There is a small misinterpretation of a point in LoTR, given early in the interview. It’s claimed that… “Theoden arrests him [Eomer] because he did not strictly apply the law” in the case of meeting Strider when riding out on the wold. But it’s stated in the book that Eomer was arrested and imprisoned because he had openly and actively … “threatened death to Grima” [the king’s counsellor] while in his lord’s hall. He had also gone riding north with his household men… “without the king’s leave, for in my absence his house is left with little guard.”

* The new open-access journal Leeds Medieval Studies now has two issues online, for 2021 and 2022. I’ve added it to my JURN. These opening issues include “The Animality of Work and Craft in Early Medieval English Literature” (animals working alongside humans), and also a review of the book The Natural World in the Exeter Book Riddles. Good preparation for the forthcoming “Tolkien’s Animals” special issue of Journal of Tolkien Research by the sound of it. The Leeds Medieval Studies editors are also interested in “the study of modern medievalisms”, by which they presumably mean 19th and 20th century medievalisms rather than ‘early modern’. Their new journal is…

“the successor to and continuation of Leeds Studies in English (founded 1932)”

Since Tolkien was at Leeds, it would be natural to imagine that they might be open to a possible ‘Tolkien special-issue’ at some point.

* There’s a new Nick Groom repository citation for his forthcoming article ““The Ghostly Language of the Ancient Earth”: Tolkien and Romantic Lithology”. This effectively brings news of a new Walking Tree book for 2023, The Romantic Spirit in the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien. There was a call for papers for this book a couple of years ago, with a deadline at the end of 2020. Possible topics then included, among others…

– The pre-Raphaelites, Birmingham and the T.C.B.S.

– The fairy-tale tradition (Brothers Grimm and others).

– The Romantic spirit in […] Tolkien’s predecessors and contemporaries.

– Romanticism in other art forms (music, visual art etc.) and its connections to Tolkien.

Sounds good, and I now assume it’s likely to appear in 2023. The “Lithology” in Groom’s title refers to the understanding and classification of rocks and their physical formations.

* And finally, Jack Kirby and Tolkien. What a Kirby-krackle of a combination. The open Creative Commons 2018 article “Darkseid’s Ring: Images of Anti-Life in Kirby and Tolkien” explores the parallels.

Pangur Ban in translation

My first try at a translation of “Pangur Ban”. A 9th century cat poem, written in Old Irish by an anonymous Irish monk and scholar.

PANGUR BAN

I and my white Pangur Ban,

Are a man and a cat each to his own,

He preens to pounce on a granary mouse,

I leap on some lost word on loan.

I want only quiet with my open book,

Thus I seek no fame from my pen,

Even my Pangur gives me no look,

As he guards a miscreant’s den.

He gladly flicks his tail and I my tales,

All alone in our silent chamber,

Finding endless sport which never pales,

hunting always the errant stranger.

In stoic Pangur’s path one will stray,

Then heroic struggles, valour and death!

For my part, I too will pounce and slay

Some difficult crux with rolling breath.

His sharp eyes can pierce all my walls,

Or roundly compass the floating mote,

Though my own age-dimmed sight appals,

In the light of distant ages I lift and float.

A power of joy is in his swiftest move,

His sharpest claw darting down and out!

I too am swift to joyous pen, when I prove

Some dearly-loved and devilish doubt.

Pangur and I are always like this,

Neither of us troubles the other,

Each of us starts to play at his own art,

Then finds his finish full of bliss.

He is made perfect, master of his trade,

Day and night he works and schemes,

I perform my own work, even in dreams,

Marking wisdom in what man has made.

Tolkien Gleanings #24

* Forthcoming in 2023, the book Tolkien’s Hidden Pictures: Anthroposophy and the Enchantment in Middle Earth. Here “anthroposophy” sounds like a horrible disease, but it refers to “the spiritual esoteric insights of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy”, which the author finds to be hidden in Tolkien’s works. The book runs to 144 pages and is due in February. The table-of-contents is available and suggests the reader must also tangle with Jung (groan…). Still, it looks serious and interesting. I see the author is also giving a talk about the book at Rudolf Steiner House in London, UK, on 28th March 2023.

Steiner was an Austrian who came of age in the 1880s and died in the mid 1920s, after contributing to the new flux of ideas around matters such as: children and education; soil health, food and mind-body holisism; and the various new fields of ‘spiritual research’ which purported to be scientific in approach. He’s certainly someone whom Tolkien would have heard and read about circa 1902-1929, among many others, and not least because he had ‘re-interpreted’ German fairy tales in esoteric ways and as a theosophist had evinced a public interest in Atlantis. Later Tolkien would also have heard about Steiner’s ideas from a fellow Inkling… “As an anthroposophist influenced by Rudolf Steiner, Barfield was a believer in the evolution of consciousness”. Lewis also walked with “anthroposophist friends, Cecil Harwood and Walter O. Field”. However Tolkien was surely both savvy and religious enough to resist such ideas, while still sympathising with their key cause — a profound spiritual discomfort with a fast-emerging and apparently god-less post-1919 ‘modern world’. Like Lovecraft, one imagines that he would have freely taken a few notions from theosophy, anthroposophy etc, in order to harness them to his own unique creative imagination. On the face of it then, there could have been some tangential influence and possibly prior to The Lord of the Rings. The forthcoming book evidently looks into that in some depth.

* I found another Fornet-Ponse article, one of many which seem to be surfacing in 2022 due to open-access deposit requirements. So far the university repository has no unified page for him that also lists all the new material, though the various aggregators can get at the PDF files. One such is “Tolkien, Newman und das Oxford Movement” which is in German and from the journal Hither Shore in 2010. It’s of interest since it relates to the influence of Cardinal Newman on the younger Tolkien. The author finds a “very meager state of research on this topic”, then examines “Newman’s conception of conscience” with particular reference to “the intuitive character of moral sense” in decision-making. Then he seeks traces of this in Tolkien’s work. He finds that decision-making in LoTR often rests not only in rational considerations, but also on subjective feelings and interpretations — which are nevertheless aligned to a moral sense that arises from a clear view of good and evil.

* Luna Press has a new 35-minute YouTube interview with scholar and collector Oronzo Cilli, hot from his recent home-town book-launch and panel discussion event. Here Cilli talks (in Italian only) about his Tolkien’s Library: An Annotated Checklist (second revised and expanded edition), a book due at the end of January 2023. Though it’s in Italian, the YouTube transcript can be translated and the gist extracted…

Cilli: I started because I was curious. I wanted to understand which books Tolkien had to hand, which book he had read. And so I started making some notes, just to collect the information about the books of his library – some of these had gradually appeared via collectors’ auctions. Then I started talking to collector friends, those who had works which were signed by or belonged to Tolkien, and I noted whatever information was in these, such as his own annotations in the margins [or on paper slips]. This collection grew and grew, and became far more than ‘just a list’. Then I started annotating! The biggest challenge was finding certainty that ‘this was the right book’ because you needed to analyze the differences between editions. In the beginning I didn’t think of it as a publishable book. [Then I spoke to Tom Shippey, who saw the potential for this to become a book]. [It has since become something of a group project for Tolkien scholars, as suggestions and revisions have poured in for a second edition]. [For the forthcoming second edition] I revised the text, I double checked. I had kept track of items that needed to be updated. New books had appeared, there were auction information sheets, and two German professors helped me to ‘harmonize’ my writing of titles in German. And then I integrated all the other sets of suggestions and lists that I have from scholars . So in the second edition there are over 500 books that are new additions. And I tried to better explain some of my choices. I also took the advice of some reviewers on the arrangement of the book. I have chosen to divide the book. There is now a Section A and Section B. The Section A has only the books which with certainty we know that were Tolkien’s. Then in Section C I talk about all the works done by Tolkien. Ranging from the articles for debates at King’s College or at Oxford, or in academic journals or books by him. I also did a search on where and if these were published and where they can be found today [up to the year 2022]. There is another section on interviews and reviews of Tolkien, with some additions that escaped me in the first edition. [He then goes on to describe other sections].

* “Tolkien And The History Of Tongues”. A 40-minute lecture by Tom Shippey at the University of Oxford, given in September 2018. Now a handy .MP3 audio-only file, for those with less than the ultrafast broadband required by the chunky official video-only version.

* And finally, “When did Gandalf first meet hobbits?”.