I’ve found a new and seemingly previously-unrecognised potential source for the name of “Bingo”, Tolkien’s original name-idea for Frodo in The Lord of the Rings. “Bingo Bolger-Baggins” was the initial name. The matter of this initial naming has puzzled many, despite it echoing “Bungo”, who was Bilbo’s father in The Hobbit. I’ve previously casually looked at the name in relation to the advent of the later modern commercial game of “Bingo” (seemingly in the 1950s as a replacement for “Lotto”). As part of another essay I also glanced at the idea that the common exclamation By Jingo! became in some trades the slang contraction of “Bingo!”.

Now a find of the popular book Merrie games in rhyme: from ye olden time (1886, London) reveals that “Bingo” was around in the culture of Tolkien’s childhood. This book of children’s games and songs was published six years before he was born. Its very first song-game is the “Bingo”…

The author the Hon. Emmeline Plunket is now better known among historians of astronomy for her scholarly Ancient Calendars and Constellations (1903, aka Calendars and Constellations of the Ancient World), and she thus appears to have been a scholar of Biblical and related astronomical systems — as well as a collector of the songs of her native land. She thus seems a reliable source, and the song is not a Victorian confabulation.

A publication review of Merrie games in the Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art picks out four song-games headed by ‘Bingo’ — “There is ‘Bingo’ and the ‘Muffin Man'” — thus implying that the song-games were then common-knowledge even among parents and nannies and that their mention would ‘hook’ interested readers. Curiously the review disparages the artistic design — it was deemed not sumptuous and ornate enough for late-Victorian tastes! A short welcoming review of the book in The Antiquary also frowned on the ornate design, though for reasons left unstated.

What of scholarly attention in the modern period? Well, the book is cited, but not evaluated for authenticity, in the Opie’s The Singing Game and also in English County Songs: Words and Music. But otherwise it appears to have been totally ignored by later books.

Is there then any other good evidence for the existence of “Bingo” in English play-culture? Yes, two items can be easily found via search.

1) Tales of the Yorkshire Wolds (1894) cites… “the ancient song of ‘Bingo'” being played by the brass band at a churchyard gala at Cragside, while children nearby have gone on to play “a screaming game of kiss-in-the-ring” on the lawns.

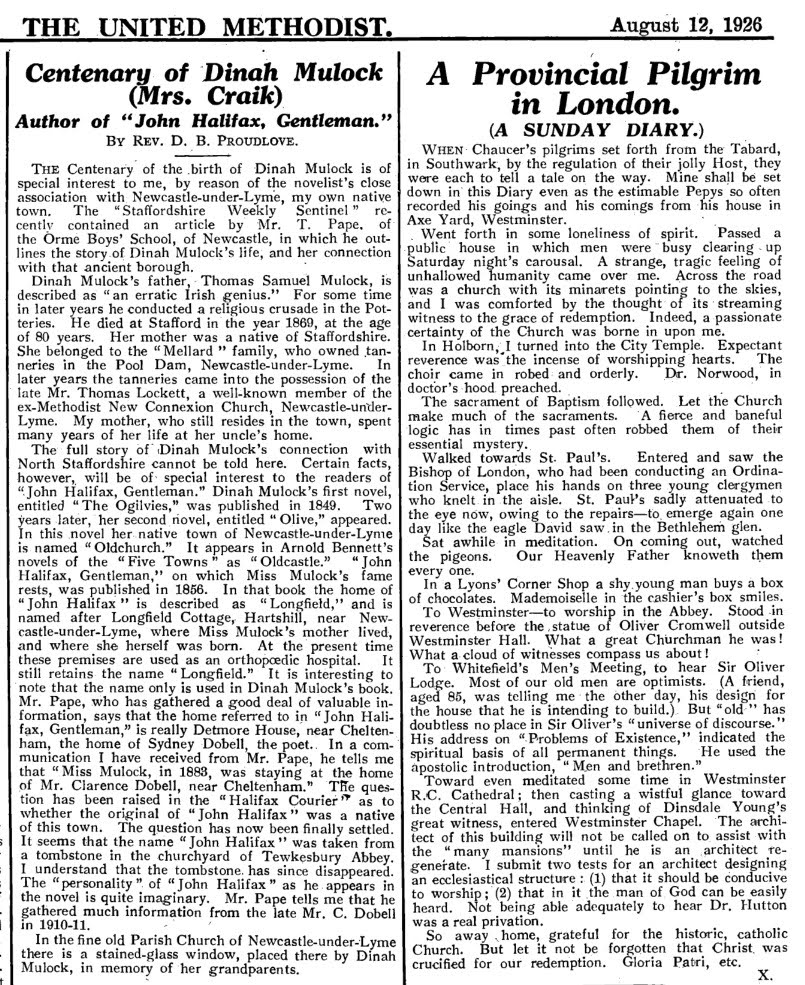

2) Cornish Feasts and Folk-lore (1890) records… “Bobby Bingo, game of” as “very common” around Helston in Cornwall. Which links it with my recent book Tolkien & The Lizard: J.R.R. Tolkien in Cornwall, 1914 (2021). I there established that Tolkien’s companion on this seminal holiday was a musician and scholar of chant-song, and someone who had formerly been for many years the curate of Porthleven — which is the coastal port for the adjacent town of Helston and its outlying hamlets such as Godolphin.

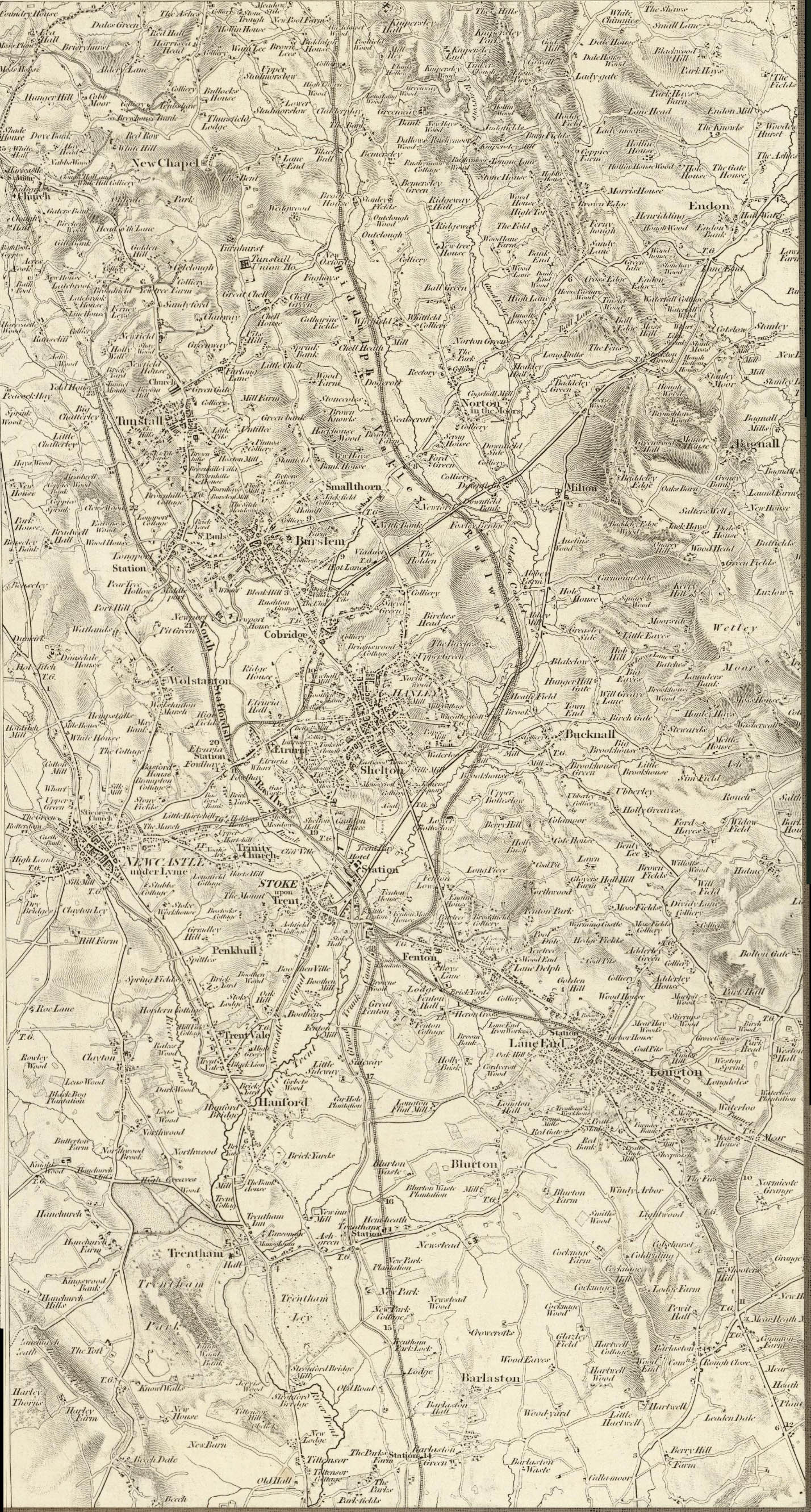

3) It was also noted at Stone in mid Staffordshire circa 1900, as a circle/dancing game (Trans. North Staffordshire Field Club, 1901).

Thus the game-song existed as far apart as Yorkshire and Cornwall, and in mid Staffordshire, albeit late in the Victorian period and after the publication of Plunket’s popular Merrie games.

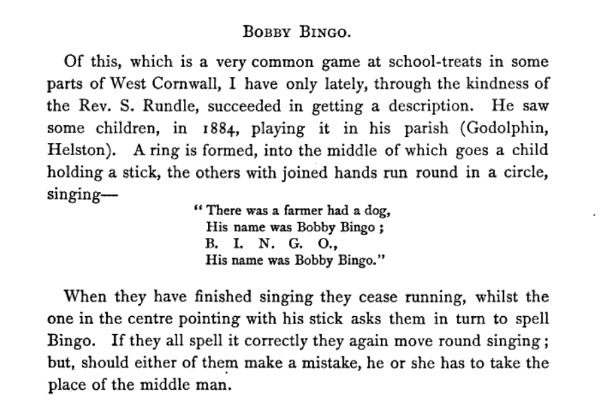

I then searched for pre-1885 occurrences. This led me to Gomme’s A Dictionary of British Folklore (aka Folk-lore). The Dictionary was actually a series, and the book is thus un-findable under that title at places such as Hathi and Archive.org. It is actually to be found online under the title The Traditional Games of England, Scotland and Ireland : with tunes, singing rhymes and methods of playing (1898, 2 Vols. in the Dictionary of British Folklore series). From Vol. 1 tumbles a wealth of detailed lore on “Bingo”…

I’m pleased to find here another Potteries children’s song collected by Miss Keary. Fellow Tolkienians will also note the prominence of ‘Sting’ and a ‘Ring’ here, both items rather well-known to readers of The Lord of the Rings.

Regrettably Gomme omits all dates from correspondents and sources, so one can’t tell if some of these song-games pre-dated the popular publication of “Bingo” in a book aimed at children. However the final note in the article, usefully reprinted from Northamptonshire Notes and Queries, points out that “Byngo” was the name of the dog in the song “The Franklin’s Dogge” aka “Ye Franklin’s Dogge”. On tracking this down, it refers to a footnote in The Ingoldsby Legends as collected and published in the early Victorian period by the Rev. Richard H. Barham. His note gives a “primitive ballad” sung in spelling-out form (the same as the later children’s song-game). The song was had via a “Mr. Simpkinson from Bath” in Somerset and is as follows…

A franklyn’s dogge leped over a style,

And his name was littel Byngo!

B wyth a Y — Y wyth an N,

N wyth a G — G wyth an O–

They call’d him little Byngo!This Franklyn, Syrs, he brewed goode ayle

And he called it Rare goode Styngo!

S, T, Y, N, G, O!

He called it Rare goode Styngo!Nowe is not this a prettie song?

I think it is bye Jyngo!

J with a Y– N, G, O–!

I swear it is by Jyngo!

A “franklyn” was a medieval term for a freeman [farmer?] who owned land and property, but was neither a peasant serf nor a noble. My suspicion would be that the word is perhaps a small embellishment to give a more ye olde flavour to an original folk-source, since the phrase “old man” might fit there and sing better. But this text can be found given in The Ingoldsby Legends editions of 1866 and 1852, and thus it clearly pre-dates the later child-song collectors of the 1880s and 90s. In its B-I-N-G-O spelling form it correlates well with the later children’s forms.

Searches suggest that the children’s song-game of “Bingo” appears to have been forgotten by the early 1930s, and earlier meanings would have been swept away by the advent of the bingo gaming halls of the 1950s and 60s. Though interestingly the ‘piecing out’ element could be seen as being kept, but transferred from alphabet letters to what had previously been called “Lotto” numbers. Note also that the mid 20th century bingo-hall balls ‘leap’ in the air like little dogs (numbered ping-pong balls in compressed-air ‘blower’ cages were used to pick random numbers, before the advent of digital methods).

Yet in Tolkien’s early childhood the song-game “Bingo” was evidently a well-known part of children’s play culture in England, especially so circa perhaps from 1880-1905. It was also widespread, being found as far apart as Yorkshire down to the tip of Cornwall, and from Lincolnshire across to Shropshire. There is one early example that appears to be a tavern ale-song from circa the 1840s in Somerset. If the publication of this song is the origin of a game-song’s later spread, or was simply an early random survival of something already widespread in the 1840s, must now remain forever unknown.

As for Tolkien, “Bingo” could well have formed: i) part of Tolkien’s own games in young and middle childhood; ii) been encountered still alive in Porthleven and around Helston in Cornwall in the summer of 1914, or in mid Staffordshire when he was there; iii) and/or been a focus of interest via a 1920s encounter with the publications of the English song and folk-lore collectors of the 1880s and 90s, especially in pursuit of “the little dog leaped…” relic fragments from “Hey Diddle Diddle” — a nursery song we know Tolkien was very interested in and which he incorporated into The Lord of the Rings in the form of Frodo’s tavern-song at Bree.

Of course, I should say that it’s also well known that his young children had toy Australian koala-bears named the Bingos. There was a ‘Bingo Koala’ brand of stuffed toy bear sold circa 1928-30, and which looked much like normal teddy-bears but were grey-white.