I’m not sure if this has been suggested before, but I can find no trace of the suggestion. Here is yet another possible solution to the genesis of Tolkien’s word “hobbit”. That it came from his mind musing on, while marking exam-papers, the name of “Coalbiters”.

This being what would become the pet name for a group of his literary fellows some years later, the name arising from the Icelandic Kolbitar which was a euphemism for dull lads who laze by the hearth-fire when there is work to be done…

“youths who were indolent and dull and who lay in the ashes by the fire during the day, the so-called coal-biters.” (Grundriss der Germanischen Philologie).

The name being doubly fitting for Oxford professors because, as masters, they presumably had hands stained with black ink from their daily labours and were also liable to carry smudges of chalk (as if they had been lazing in fire-ashes) gained by labouring at good old-fashioned blackboards. But also fitting for musing on lazy lads who do not trouble to complete their exam-papers.

Anyway, the famous word “hobbit” was jotted down at the end of a long stint of marking school exam-papers, possibly as early as 1926 but likely some years later. Tolkien encountered a blank sheet from the final paper. On this he spontaneously wrote…

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit”.

… and thus began The Hobbit. My suggestion is that line could have arisen, either prior and unbidden in his mind or in a mere moment’s consideration, from musing on coalbiters…

“In a hole in the ground there lived a coalbiter … hole-biter … ho..bit … hob-bit.”

Tolkien being presumably aware that hob was also a word from the fireside hearth (see below) and thus connected at least in circumstance with Kolbitar. He would also have known of ‘Lob Lie-By-The-Fire’ from northern England, and the modern German ‘Kobold’ as a common name for a ‘house spirit’.

Even more speculatively, the “hole” might even be inferred if he had then recalled how the word “hob” was used in Cheshire. From a key topography of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, on which Tolkien was by then the contemporary expert…

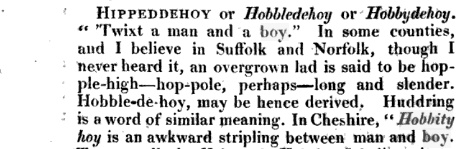

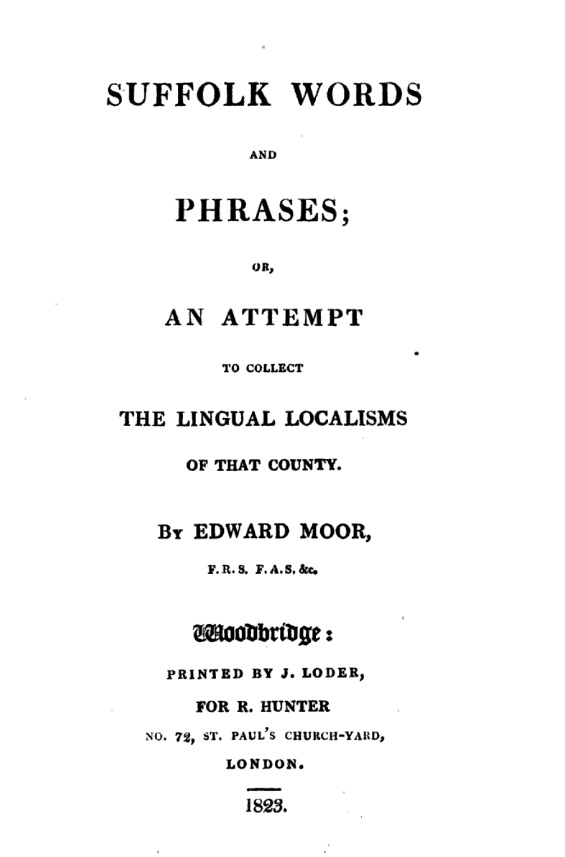

“In Cheshire, Hobbity-hoy is an awkward stripling between man and boy” (1823)

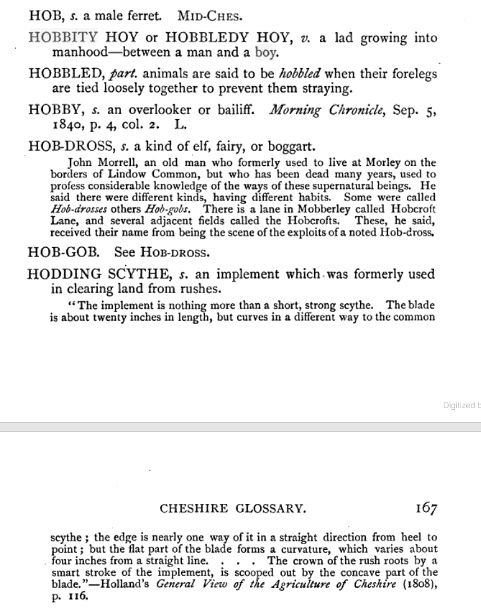

This link with a hole could be inferred from “Hobbity-hoy” since it likely derived in Cheshire from the likeness of the lithe and nervously energetic boy to a male ferret, which the Cheshire Glossary has it was called a “hob” in Cheshire and elsewhere.

Ferrets having of course long been used for rabbit hunting in holes, and having an ashy-looking underside of fur. After hunting in a sandy burrow, this pale underside would likely look even more as if the creature had been “lying in the ashes of a fire” — similar to how the coalbiters boys were imagined.

This word is also not incompatible with “hob” used in the olde-time fireside sense. In the era of big broad medieval fireplaces, a “hob” indicated the small shelves set in the corners of the hearth, above hot grates, on which tankards of cider and ale were kept hot. One can then imagine that the lid of a loose-lidded tankard would thus start to “pop” up and down when it became too hot and air needed to escape and the tiny vent-hole was insufficient, much like the action of a weasel or ferret popping his head out of a rabbit-hole and with the same flash of white chest-fur and shining eyes as some bubbling foam spilled up and out. One here also recalls the real tradition of lacing good cider with a dead rodent to help start the yeasting process. Could this be the origin of the phrase “pop goes the weasel”, when it was laughingly observed by the hobbity-hoy boys at the winter fireside that the dead weasel or ferret consigned to the brew on the hob “has cum’ alive again” and “iz tryin’ to pop out”?