Arnold Bennett, “The People of the Potteries” from Cassell’s Family Magazine, January 1911.

Monthly Archives: August 2020

“Simon Fuge” in free audiobook

Arnold Bennett’s masterpiece “The Death of Simon Fuge” is now available as a public-domain two-hour audiobook read by David Wales, in Librivox’s new release of The Grim Smile Of The Five Towns.

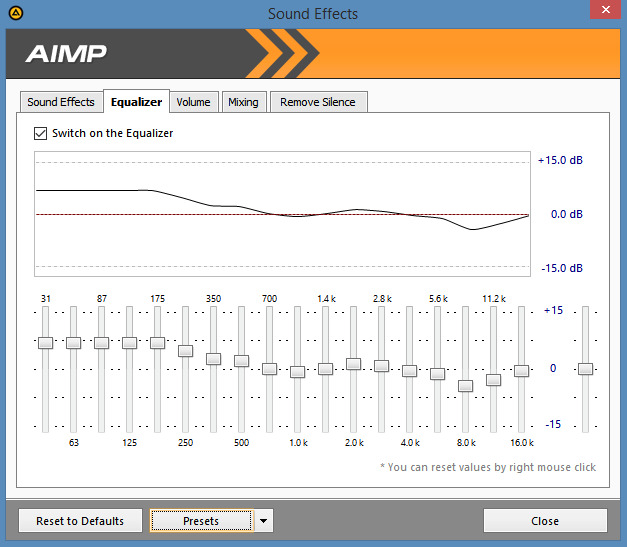

It’s a pretty good lively reading with some subdued attempt at dialogue characterisation, read by an older man with what is probably a New England American accent. He goes at it rather fast, and is a little sibilant when heard on headphones. But the graphic equaliser and real-time speed-shifter of a good audio player (such as AIMP) will fix that…

Speed: 0.94 or 0.95.

EQ settings to start tweaking from:

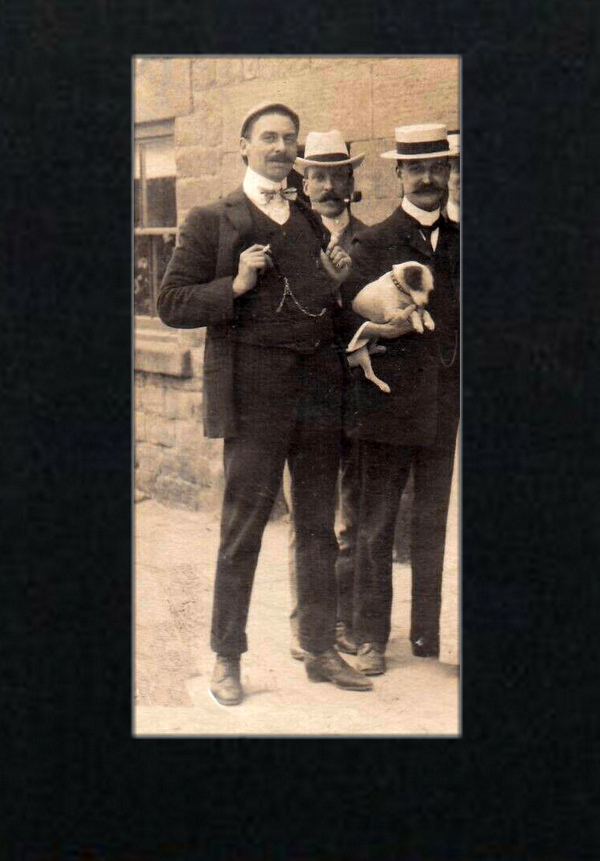

Sadly there’s not a single illustration for “Fuge” to be had, but this picture from North Staffordshire in circa 1902-03 gets pretty near to the three main male characters, with the visitor Mr. Loring being the one standing behind and with a pipe…

Well-dressing on Mow Cop

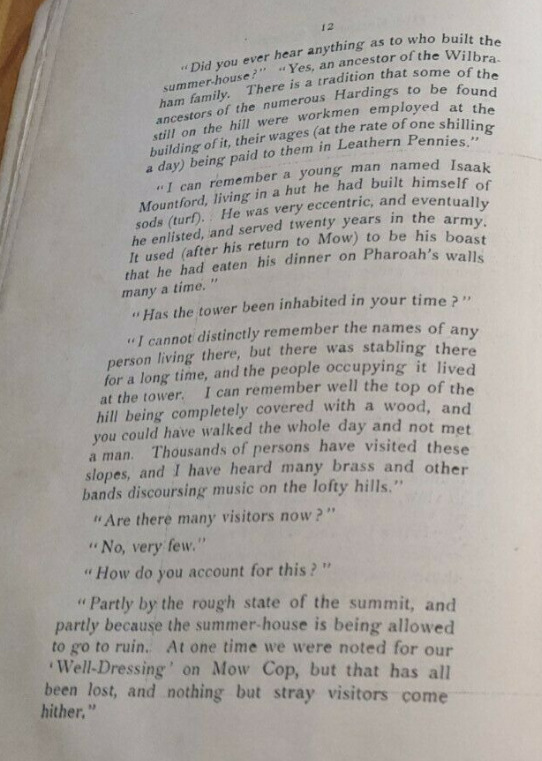

Part of an interview with an old man of Mow Cop, published in a booklet on A Short History of Mow Cop in 1907 (aka Mow Cop and its Slopes: A Short History). It’s a £10 eBay listing and I can’t get more of it.

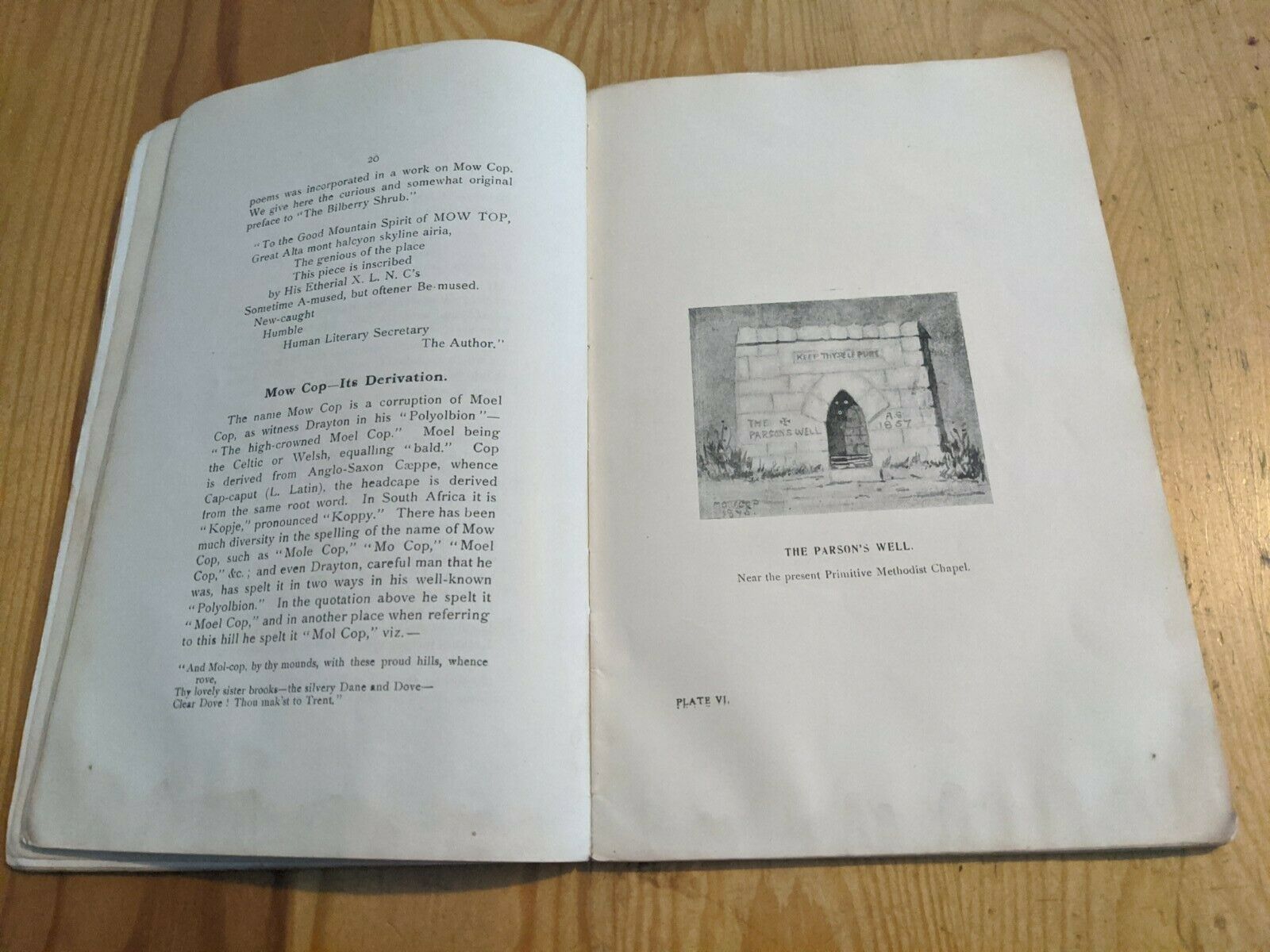

The author obviously had the gumption, which many Victorian antiquaries did not, to interview a local old man and to print his memories. The man recalled that the top of Mow Cop used to be extensively wooded. How that came about would be interesting to know. Was it planted for timber or was it a natural and scrubby re-wilding? A thirty-year growth would be about right for the 1850s, if the economic slump of the 1820s and then the 1840s had caused widespread abandonment and also removal of the sheep — which would otherwise devastate such uplands.

Importantly for local folklore, he recalled that there used to be annual well-dressing ceremonies, and the book shows a drawing of one well. It might have slipped my memory, but I don’t recall that I’d heard anywhere else that there had once been an annual well-dressing event on Mow Cop. There is also a Woodcocks’ Well School on Mow Cop, so that may give another name.

That might perhaps be an inspiration for local people today, in terms of re-starting the well-dressing and also pairing it with summit tree-planting and litter-picking along the watercourses and around the wells. There was also an Eisteddfod at nearby Kidsgrove from 1913-1955, in which Mow Cop schools won prizes. So singing might feature too.

Open all hours

An interesting little snippet of fact, for those writing historical fiction and accounts of Burslem. We might casually assume that a modern 5.30pm closing-time had been norm since the 1860s, but it wasn’t so. Actually the shops, and presumably also the eateries, were open very late into the evening. I guess the attitude was, “if there’s trade to be had, we stay open”.

This is from a 1953 Coronation booklet issued by the town’s Traders, which gives a short outline history of the trading associations.

Treasure from Biddulph

I’ve found an interesting 1975 article which, in a roundabout way, throws a little more light on possible Sir Gawain routes into North Staffordshire…

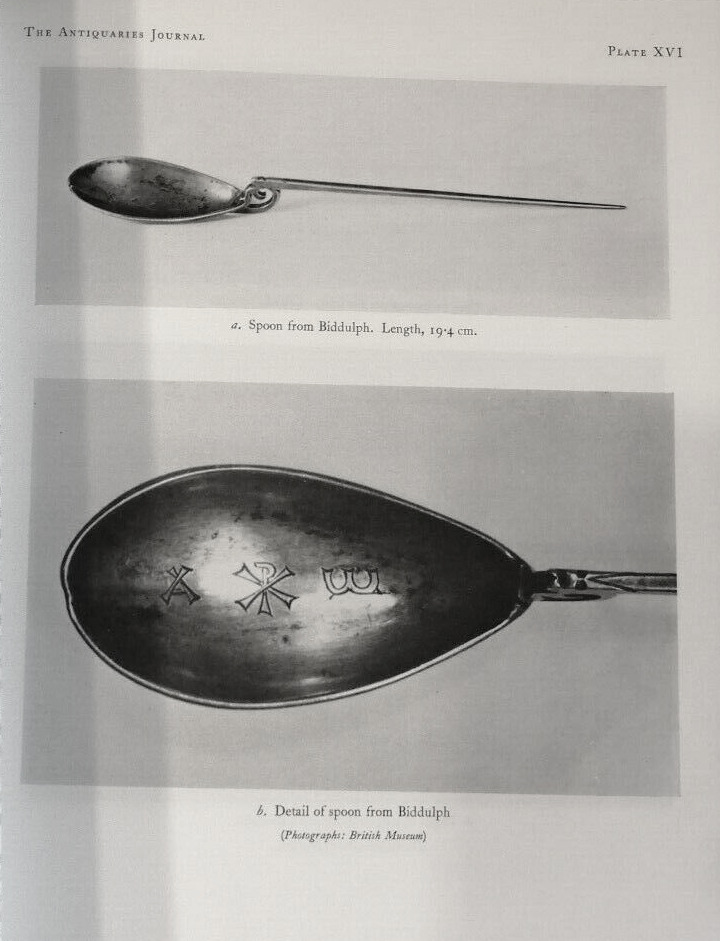

Kenneth S. Painter, “A Roman Christian silver treasure from Biddulph, Staffordshire”, The Antiquaries journal: being the journal of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 55, 1, 1975, pages 62-69.

The Archaeology Data Service has a brief summary…

A 4th-century silver spoon with Christian symbols is the survivor of a hoard, originally of four spoons, from Biddulph. Notes by A. W. Franks in 1886 identify the find spot as Whitemore Farm [aka White Moor Farm, between Biddulph and Congleton]. Also discussed are the dating, place of manufacture, symbolism, and the significance of the find place for understanding the local Roman road system.

Sadly The Antiquaries Journal is not online for free, but the article is scanned and on Cambridge Core. There one finds the abstract from the article itself…

In 1972 the British Museum bought a fourth-century silver spoon with Christian symbols. An undated document acquired with the spoon showed that it was the survivor of a hoard from Biddulph, Staffordshire. In 1973 notes made in “January 1886, about the discovery of the spoon, were found in a notebook compiled by A. W. Franks. The newly acquired spoon proves to have been one of a hoard of four spoons found at Whitemore Farm, Biddulph. The find-place of the spoon [and another hoard at Wincle] suggests a possible direct link between Chester and Buxton, while its dating adds to the sparse testimony for late-Roman life in the north-west of the province. The style of the lettering may indicate that the spoon was made in the East Mediterranean, and the Christian symbolism adds to the stock of evidence about the cult in the western Roman Empire.

A recent eBay listing usefully furnishes this main picture of the spoon…

On the local Roman road network the article offers…

“the probable Roman road which crosses Congleton Edge at Nick i’Th’Hill and runs [west] via Astbury to Middlewich [… and, based on other finds] there may well have been a continuation of the Middlewich-Astbury Roman road on towards Buxton … This would have been a convenience … providing more direct communication from Buxton to Chester”.

Another, purely oral, survival from Roman times was published as a note in a book in 1913. The word tallet — meaning the hay-loft above a stable — had survived to the modern period from ancient Roman times…

the English word tallet, which is found to-day in common use in the dialects of Cheshire and all the W.Midl[ands] … The remarkable point about the preservation of this word is that it never once occurs in the whole range of English literature down to the nineteenth century, when Blackmore introduced it in his Lorna Doone. Through all these centuries it has steadily persisted in the spoken language without any help from the world of letters, linking the modern rustic to the early Briton and the subjects of Julius Caesar. (Rustic speech and folk-lore, Oxford University Press, 1913).

A Staffordshire wonder? Possibly not.

On 15th May 1712, the old Spectator published the following account…

“A certain person having occasion to dig somewhat deep in the ground, where this philosopher [Rosicrucius] lay interred, met with a small door, having a wall on each side of it. His curiosity, and the hopes of finding some hidden treasure, soon prompted him to force open the door. He was immediately surprised by sudden blaze of light, and discovered a very fair vault. At the upper end of it was a statue of a man in armour, sitting by a table, and leaning on his left arm. He held a truncheon in his right hand, and had a lamp burning before him. The man had no sooner set one foot within the vault, than the statue, erecting itself from its leaning posture, stood bolt upright; and, upon the fellow’s advancing another step, lifted up the truncheon in its right hand. The man still ventured a third step, when the statue, with a furious blow, broke the lamp into a thousand pieces, and left his guest in a sudden darkness.

Upon the report of this adventure, the country people soon came with lights to the sepulchre, and discovered that the statue, which was made of brass, was nothing more than a piece of clock-work; that the floor of the vault was all loose, and underlaid with several springs, which, upon any man’s entering, naturally produced that which had happened.

Rosicrucius, say his disciples, made use of this method to show the world that he had re-invented the ever-burning lamps of the ancients, though he was resolved no one should reap any advantage from the discovery.”

This tale was later embellished and claimed for Staffordshire, in the book The Rosicrucians: Their Rites and Mysteries, by Hargrave Jennings. This had gone to a 4th edition by 1907. Here is the story as tickled up by Jennings, who spuriously references the Staffordshire historian Dr. Plot.

SINGULAR ADVENTURE IN STAFFORDSHIRE

DR. PLOT, who was a very well-known and reliable man, and a painstaking antiquary and writer of natural history, in his History of Staffordshire, published by him in the time of Charles the Second, relates the following strange story:

That a countryman was employed, at the close of a certain dull summer’s day, in digging a trench in a field in a valley, round which the country rose into sombre, silent woods, vocal only with the quaint cries of the infrequent magpies. It was some little time after the sun had sunk, and the countryman was just about giving over his labour for the day. Dr. Plot says that, in one or two of the last languid strokes of his pick, the rustic came upon something stony and hard, which struck a spark, clearly visible in the increasing gloom. At this surprise he resumed his labour, and, curiously enough, found a large, flat stone in the centre of the field. This field was far away from any of the farms or ‘cotes’, as they were called in those days, with which the now almost twilight country was sparingly dotted. In a short time he cleared the stone free of the grass and weeds which had grown over it; and it proved to be a large, oblong slab, with an immense iron ring fixed at one end in a socket. For half-an-hour the countryman essayed to stir this stone in vain. At last he bethought himself of some yards of rope which he had lying near amongst his tools; and these he converted, being an ingenious, inquisitive, inventive man, into a tackle — by means of which, and by passing the sling round a bent tree in a line with the axis of the stone, he contrived, in the last of the light, and with much expenditure of toil, to raise it. And then, greatly to his surprise, he saw a large, deep, hollow place, buried in darkness, which, when his eyes grew accustomed a little to it, he discovered was the top-story to a stone staircase, seemingly of extraordinary depth, for he saw nothing below. The country fellow had not the slightest idea of where this could lead to; but being a man, though a rustic and a clown, of courage, and most probably urged by his idea that the staircase led to some secret repository where treasure lay buried, he descended the first few steps cautiously, and tried to peer in vain down into the darkness. This seemed impenetrable; but there was some object at a vast, cold distance below. Looking up to the fresh air and seeing the star Venus — the evening star — shining suddenly like a planet, in encouraging, unexpected brilliancy, although the sky had still some beautiful placid sunset light in it, the puzzled man left the upper ground, and descended silently a fair, though a somewhat broken staircase. Here, at an angle, as near as he could judge, of a hundred feet underground, he came upon a square landing-place, with a niche in the wall; and then he saw a further long staircase, descending at right angles to the first staircase, and still going down into deep, cold darkness. The man cast a glance upward, as if questioning the small segment of light from the upper world which shot down, whether he should continue his search or desist and return. All was stillest of the still about him; but he saw no reason particularly to fear. So; imagining that he would in some way soon penetrate the mystery, and feeling in the darkness by his hands upon the wall, and by his toes to make sure first on each step, he resolutely descended; and he .deliberately counted two hundred and twenty steps. He felt no difficulty in his breathing, except a certain sort of aromatic smell of distant incense, that he thought Egyptian, coming up now and then from below, as if from another, though a subterranean, world. ‘Possibly’, thought he — for he had heard of them — ‘the world of the mining gnomes: and I am breaking in upon their secrets, which is forbidden for man’. The rustic, though courageous, was superstitious.

But, notwithstanding some fits of fear, the countryman went on, and at a much lower angle he met a wall in his face; but, making a turn to the right, with singular credit to his nerves, the explorer went down again. And now he saw at a vast distance below, at the foot of a deeper staircase of stone, a steady though a pale light. This was shining up as if from a star, or coming from the centre of the earth. Cheered by this light, though absolutely astounded, nay, frightened, at thus discovering light, whether natural or artificial, in the deep bowels of the earth, the man again descended, meeting a thin, humid trail of light, as it looked, mounting up the centre line of the shining though mouldering old stairs, which apparently had not been pressed by a foot for very many ages. He thought now, although it was probably only the wind in some hidden recess, or creeping down some gallery, that he heard a murmur overhead, as. If of the uncertain rumble of horses and of heavy waggons or lumbering wains. Next moment, all subsided into total stillness; but the distant light seemed to flicker, as if in recognition or answer to the strange sound. Half-a-dozen times he paused, and turned as if he would remount — almost flee for his life upward,. As he thought; for this might be the secret haunt of robbers, or the dreadful abode of evil spirits. What if, in a few moments, he should -come upon some scene to affright, or alight in the midst of desperate ruffians; or be caught by murderers! He listened eagerly. He now almost bitterly repented his descent. Still the light streamed at a distance; but still there was no sound to interpret the meaning of the light, or to display the character of this mysterious place, in which the countryman found himself entangled hopelessly like a knight of romance in an enchanted world.

The discoverer by his time stood still with fear. But at last, summoning courage, and recommending himself devoutly to God, he determined to complete his discovery. Above, he had been working in no strange place; the field he well knew, the woods were very familiar to him, and his own hamlet and his wife and family were only a few miles distant. He now hastily, and more in fear than through courage, noisily with his feet descended the remainder of the stairs; and the light grew brighter and brighter as he approached, until at last, at another turn, he came upon a square chamber, built up of large hewn ancient stones. He stopped, silent and awe-struck. Here was a flagged pavement and a somewhat lofty roof, gathering up into a centre, in the groins of which was a rose, carved exquisitely in some dark stone or in marble. But what was this poor man’s fright when, making another sudden turn, from between the jambs, and from under the large arched vault of a Gothic, stone portal, light streamed out over him with inexpressible brilliancy, shining over everything, and lighting up the place with brilliant radiance, like an intense golden sunset. He started back. Then his limbs shook and bent under him as he gazed with terror at the figure of a than, whose face: was hidden, as he sat in a studious attitude in a stone chair, reading in a great book, with his elbow testing on a table like a rectangular altar, in the light of a large, ancient iron lamp, suspended by a thick chain to the middle of the roof. A cry of alarm, which he could not suppress, escaped from the scared discoverer, who involuntarily advanced one pace, beside himself with terror. He was now within the illuminated chamber. As his foot fell on the stone, the figure started bolt upright from his seated position, as if in. Awful astonishment. He erected his hooded head, and showed himself as if in anger about to question the intruder. Doubtful if what he saw were a reality, or whether he was not in some terrific dream, the countryman advanced, without being aware of what he was doing, another audacious step. The hooded man now thrust out a long arm, as if in warning; and in a moment the discoverer perceived that this hand was armed with an iron baton, and that he pointed it as if tremendously to forbid further approach. Now, however, the poor man, not being in a condition either to reason or to restrain himself, with a cry, and in a passion of fear, took a third fatal step; and as his foot descended on the groaning stone, which seemed to give way for a moment under him, the dreadful man, or image, raised his arm high like a machine, and with his truncheon struck a prodigious blow upon the lamp, shattering it into a thousand pieces, and leaving the place in utter darkness.

This was the end of this terrifying adventure. There was total silence now, far and near. Only a long, low roll of thunder, or a noise similar to thunder, seemed to begin from a distance, and then to move with snatches, as if making turns; and it then rumbled sullenly to sleep, as if through unknown, inaccessible passages. What these were — if any passages — nobody ever found out. It was only suspected that this hidden place referred in some way to the Rosicrucians, and that the mysterious people of that famous order had there concealed some of their scientific secrets. The place in Staffordshire became afterwards famed as the sepulchre of one of the brotherhood, whom, for want of a more distinct recognition or name, the people chose to call ‘Rosicrucius’, in general reference to his order; and from the circumstance of the lamp, and its sudden extinguishment by the figure that started up, it was supposed that some Rosicrucian had determined to inform posterity that he had penetrated to the secret of the making of the ever-burning lamps of the ancients — though, at the moment that he displayed his knowledge, he took effectual means that no one should reap any advantage from it.

This apparently entirely spurious tale and setting (there was no ‘Rosicrucius’ either) is more fully documented by Leigh Penman, in volume 20 of Staffordshire Studies, with his long article “‘Singular adventure in Staffordshire’, or, the Tomb of Rosicrucius. Fact, fancy and folklore in the curious history of a non-existent wonder”.

Still, as a fictional story it has something to it, and may be one for some future book of ‘strange Staffordshire tales’.

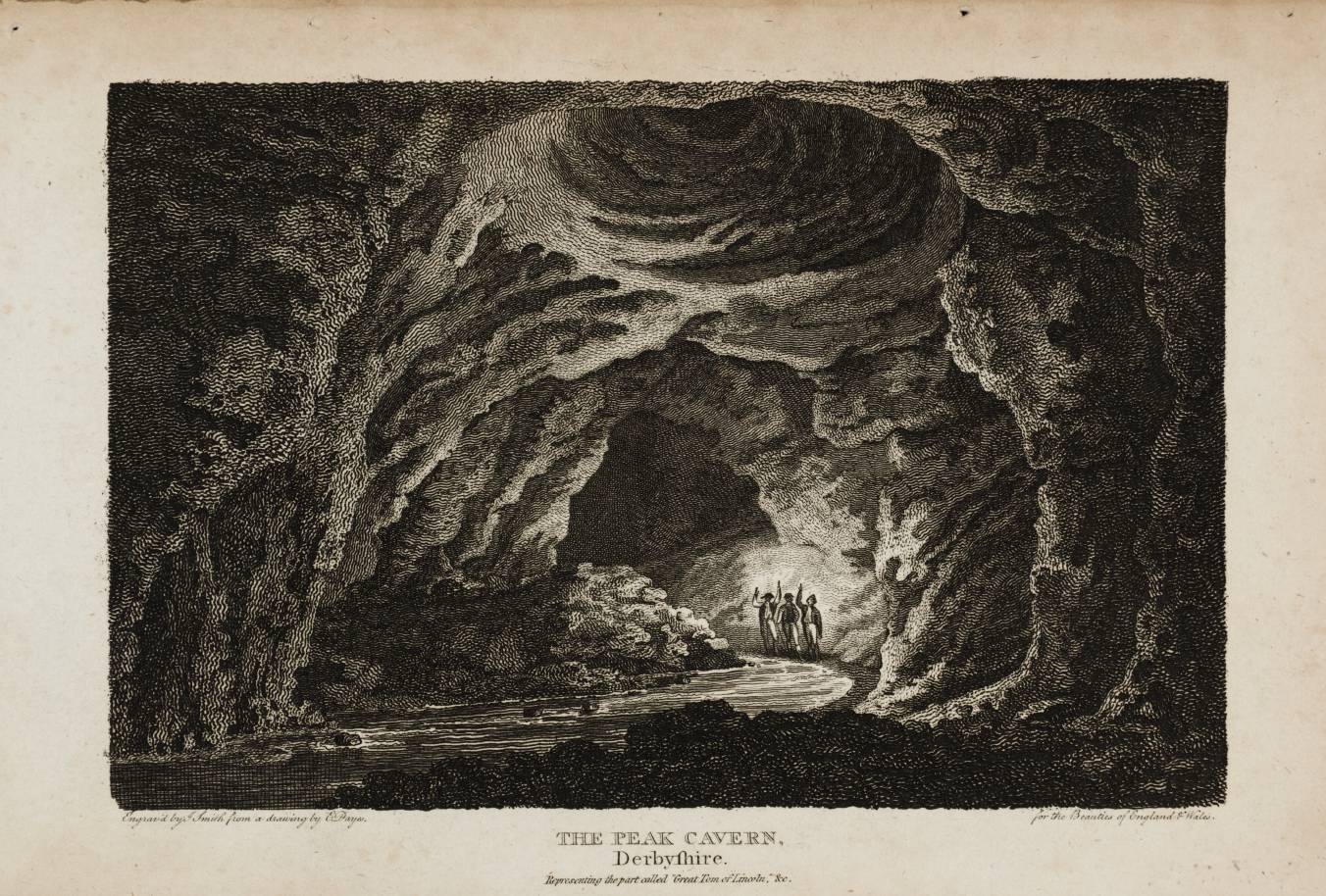

The Caverns of Derbyshire

Another local book or large booklet discovered, The Caverns of Derbyshire: being an extract from Irlande at Cavernes Anglaises. A 1914 English translation of the Derbyshire sections of a 1897 book by the pioneering cave and underground-river explorer E. A. Martel (1859-1938). It is not on Archive.org and appears to be effectively unknown, outside specialist libraries of caving history.

A more recent translation of a part of it was “A description of Peak Cavern, Derbyshire, by Edouard-Alfred Martel: a translation”, in Cave and Karst Science 45 (3), pages 113-117.

I see that there’s now a 2013 DVD documentary on Martel in German and French, being a 1995 documentary rescued from the archives. Those in the local Peak District archives might like to note that… “In addition, a limited edition of the English version is currently available” for 19 Euros. Though I don’t know how heavily it focuses on the Ireland and Derbyshire exploring. He also made a lot of other fabulous discoveries in France, Spain, Germany and Russia.