There were several bits of questionable history in The Sentinel, today. Which I fisk below…

1. Claim: H.G. Wells could look down over the industrial Potteries from his bedroom window…

“Wells’s front bedroom overlooked the sloping hill down to Etruria, and in 1888 the houses which are now opposite had yet to be built, so he had a clear view down to the industrial heartlands below. At this point, the huge Shelton Bar Steelworks was in full operation, and at night the steelworkers would vent the furnaces. … this inspired his imagination and got him thinking about the red planet Mars. He is said to have imagined the tall Martian war machines stalking about in this red glow.”

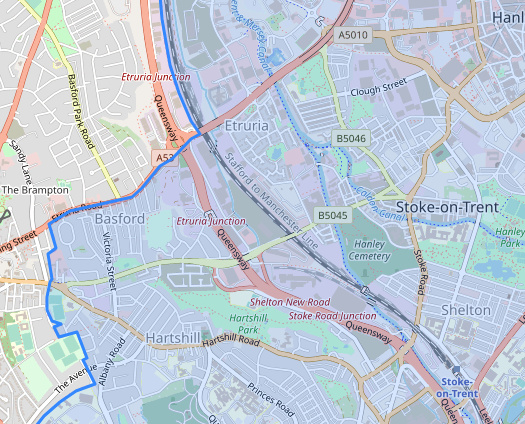

For initial orientation, here is 18 Victoria St., Basford, Stoke-on-Trent, on a modern map. The blue shading indicates the area and boundaries of Stoke-on-Trent. One can see Victoria St., under the “Basford” label.

And here is the house location on a 1879 map, with the line of Victoria St. laid out, but not yet built. I’ve precisely marked the future No. 18, via a matched overlay in Photoshop.

And here is a semi-3D terrain view showing that the house was set back from the edge of the valley, rather than on the lip. Also seen marked is the site of the Iron Works at Etruria, which was on the relatively flat land below the valley ridge.

As one can clearly see, “a clear view down to the industrial heartlands” is just not possible, even assuming less houses in the way in 1888. At best, when looking out of the left-hand upper front window at No. 18, Wells might have had the merest 2-degree sliver of a view of sky to the east, between houses that had already been built by 1879, and there might have seen there a strong red sky-glow coming through at night from the furnaces.

If Wells had then looked from the right-hand upper front window, assuming no houses in the way, by craning his neck a bit he could have perhaps have seen a view SSE over flat fields which went gently sloping away in the general direction of Stoke town. But he would not have been looking directly down onto the valley and nor would that view (if view it was) have shown him anything of Etruria.

Wells’s story “The Cone” does, however, imply that a dynamic red-sky flicker could be seen from the house with the lights out…

“… she sank down into a crouching attitude in the big arm-chair, her eyes wide open and staring out at the red lights from the furnaces that flickered in the sky”

But to get a view of the industrial valley from the house, Wells then has the two men in the story go out from the house, down the Basford Bank and then turn onto the cinder track toward what were the Etruria Woods…

“side by side down the road in silence, and in silence turn[ed] into the cinder-made by-way that presently opened out the prospect of the valley”

2. Claim: Shelton Bar Steelworks was in full operation.

Not quite. Steel-making had not yet begun down in the valley. Built around and across a former racecourse, on the relatively flat valley bottom at Etruria, in the year 1888 Earl Granville’s Shelton Bar Iron Company was about to transition to the more intensive process of making steel — but had not yet done so when Wells was there. A contemporary account of a foreign tour of the works in 1875 had thought the place rather old-fashioned even then, and it still had not transition to steel by the spring of 1888. That it was then an Iron Works is also confirmed by Wells’s own description of it as the Iron Works…

“I’ve sat in ‘Trury woods [Etruria Woods] in the springtime, bluebells all about me, and seen overhead the smoke from Granville’s (I think it’s Granville’s) Iron Works streaming by under the white clouds.”

As we can see from this quote, Wells often had views over the valley, from bits of the Fowlea Bank lane that runs steeply down behind Basford Bank, and also from the top of the Etruria Woods. But these views were not to be seen from the house at 18 Victoria St.

3. Claim: “He is said to have imagined the tall Martian war machines stalking about in this red glow.”

I wrote the book on Wells in the Potteries, and I’ve never read any scholarly claim that he was directly inspired to create the war-machines from seeing Etruria at night. The claim above is probably vaguely referencing the section in The War of the Worlds (1897), in which Wells makes a fleeing comparison of the devastation of the Martian heat-rays to the red sky of “the Potteries at night”…

“I closed the door noiselessly and crept towards the window. … There was a light down below the hill, on the railway, near the arch, and several of the houses along the Maybury road and the streets near the station were glowing ruins. The light upon the railway puzzled me at first; there were a black heap and a vivid glare, and to the right of that a row of yellow oblongs. Then I perceived this was a wrecked train, the fore part smashed and on fire, the hinder carriages still upon the rails. Between these three main centres of light — the houses, the train, and the burning county towards Chobham — stretched irregular patches of dark country, broken here and there by intervals of dimly glowing and smoking ground. It was the strangest spectacle, that black expanse set with fire. It reminded me, more than anything else, of the Potteries at night. … this was the little world in which I had been living securely for years, this fiery chaos! What had happened in the last seven hours I still did not know; nor did I know, though I was beginning to guess, the relation between these mechanical colossi [the Martian war-machines] and the sluggish lumps I had seen disgorged from the cylinder [the Martian arrival craft]. … three gigantic black things were going to and fro in the glare about the sand pits. They seemed amazingly busy. I began to ask myself what they could be. Were they intelligent mechanisms? Such a thing I felt was impossible. Or did a Martian sit within each, ruling, directing, using, much as a man’s brain sits and rules in his body? I began to compare the things to human machines, to ask myself for the first time in my life how an ironclad [war steamship] or a steam engine would seem to an intelligent lower animal.”

While it’s possible that some mechanical elements of the Iron Works at Etruria may have somewhat resembled the war-machine tripods in the night-glow in 1888, I’ve never seen any pictures of such machinery or gantry-towers that makes me think “aha! — there’s your Martian war machine”. Nor seen any letters or suchlike from Wells which noted such things. The Iron Works at Etruria is vividly and precisely described in “The Cone”, but the closest Wells gets to a war-machine in it is… “The shining black tower of the larger blast-furnace rose overhead out of the mist”.

In another autobiographical account, he…

“surveyed across dark intervening spaces, the flaming uproar, the gnome-like activities of iron foundries”

But this is from the “Margaret in Staffordshire” chapter in the late novel The New Machiavelli (1911), and as such no-one can claim that the industrial “gnomes” of Etruria might have somehow prefigured the drivers of the Martian death-machines in 1897.

4. The article’s journalist also can’t resist making an implicit and false claim on Wells for Newcastle-under-Lyme… “Newcastle’s links with the famous author”.

18 Victoria St. in not today in Newcastle-under-Lyme. Also, it was part of the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent in 1888.

The spot where the house would be built also seems to have been part of the parish of Stoke when it was still fields, prior to the incorporation of Stoke in the Borough of Stoke-upon-Trent in 1874.