Here are pages 185-229 from the weighty survey book General view of the Agriculture of the County of Stafford (1796) by William Pitt. In most of his Appendix Pitt surveys North Staffordshire, as it was on his tour of the county in 1794. While the ‘agricultural improvement’ elements of the book have probably long been superseded, tucked away in the book’s Appendix we have Pitt’s short survey of our terrain and its uses at the end of the 18th century.

Appendix to Agriculture of the County of Stafford (1796) by William Pitt (PDF)

Pitt has a page on the ancient rocks of the district, such as those at the Roaches and Ipstones, and his reactions to them. The religious nature of these reactions, bursting into an agricultural book, seem to have relevance for understanding the Gawain-poem, specifically what Gawain might have felt when first entering this landscape through the Ludchurch cleft in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight…

“This part of the country, north-east of Mole Cop [Mow Cop], is the worst part of the Moorlands, and of Staffordshire, the surface of a considerable proportion of this land being too uneven for cultivation. Large tracts of waste land here, though so elevated in point of situation, are mere high moors and peat mosses; and of this sort are a part of Morredge [Morridge], Axe Edge, the Cloud Heath, High Forest, Leek Frith, and Mole Cop, though ranking amongst the highest land in the county.

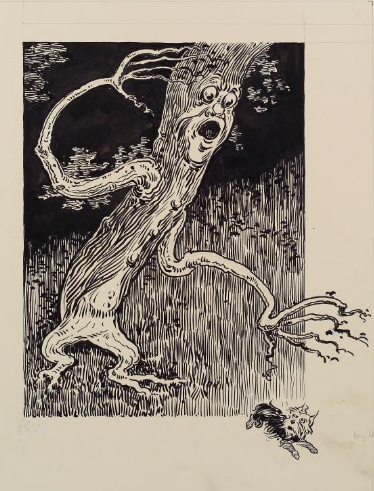

The summits of some of the hills in this county terminate in huge tremendous cliffs, particularly those called Leek Rocks or Roches, and Ipstones’ sharp Cliffs, which are composed of huge piles of rude arid rugged rocks in very elevated situations, piled rock on rock in a most tremendous manner, astonishing and almost terrifying the passing traveller with their majestic frown. Here single blocks, the size of church steeples, are heaped together; some overhanging the precipice, and threatening destruction to all approachers; and some of prodigious bulk have evidently rolled from the summit; and broke in pieces. These stupendous piles, the work of nature, are a sublime lecture on humility to the human mind; strongly marking the frivolity of all its even greatest exertions, compared with the slightest touches of that Almighty […] The speculative mind, in endeavouring to account for their origin or formation by any known laws, agency, or operation of nature, is lost in amazement, and led to exclaim, with the Egyptian magicians, “this is the finger of God” for the most superficial observer may perceive that it is his work.

Leek Rocks or Roches, are composed of a coarse sandy grit rock; those of Ipstones have for their basis gravel, or sand and small pebbles cemented together.”

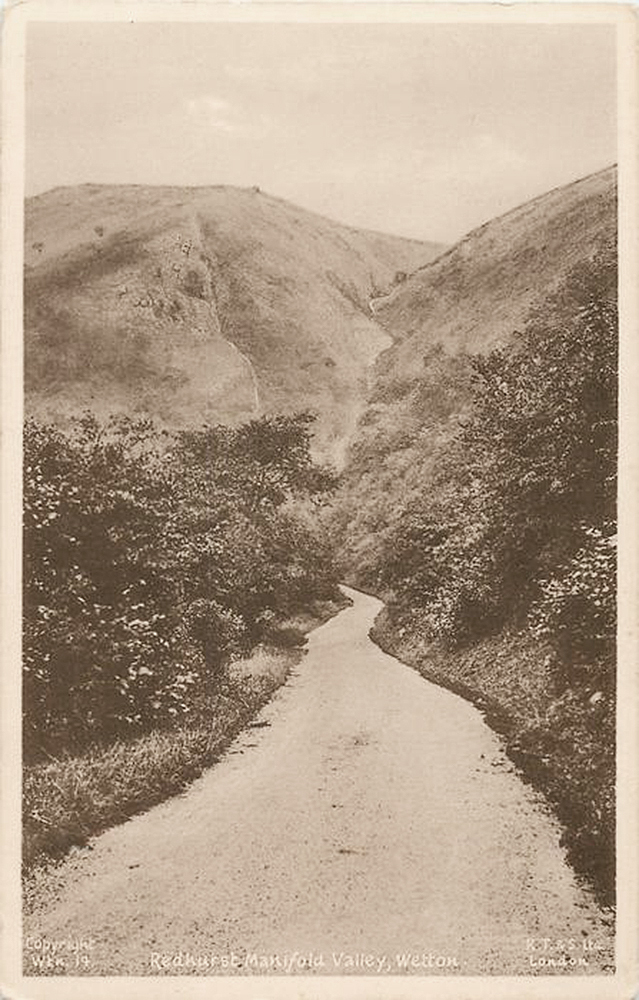

The Appendix only has one diagram. Thomas Wedgwood, over at nearby Etruria had not yet invented photography at that point, and an agricultural book couldn’t expect fine engravings. So pictures seem called for here. The Roaches and Wetley Rocks are well photographed, but what of Ipstones? Well, there are some pictures to be had. I found some pictures of the Gog rock which is just west of Ipstones, and one of the rocks had a folly-bridge which enabled visitors to reach the top from the adjacent moorland. Pitt calls the rock type here… “(breccia arenacea) or coarse plum-pudding stone and seems like sand and small pebbles cemented together”. Who built the bridge? Unknown, but one local walk guide talks of the ‘Belmont estate’ and Belmont Hall is nearby and within walking distance.

The site appears to have had, and possibly still have, a substantial spring. In 1967 there’s a record of the adjacent Intake Farm being granted a licence to extract “700,000 gallons per year at Stakebank Wood” from a spring there. Presumably this is for agricultural use, as I can find no ‘Gog & Magog Mineral Water’ brand, etc.

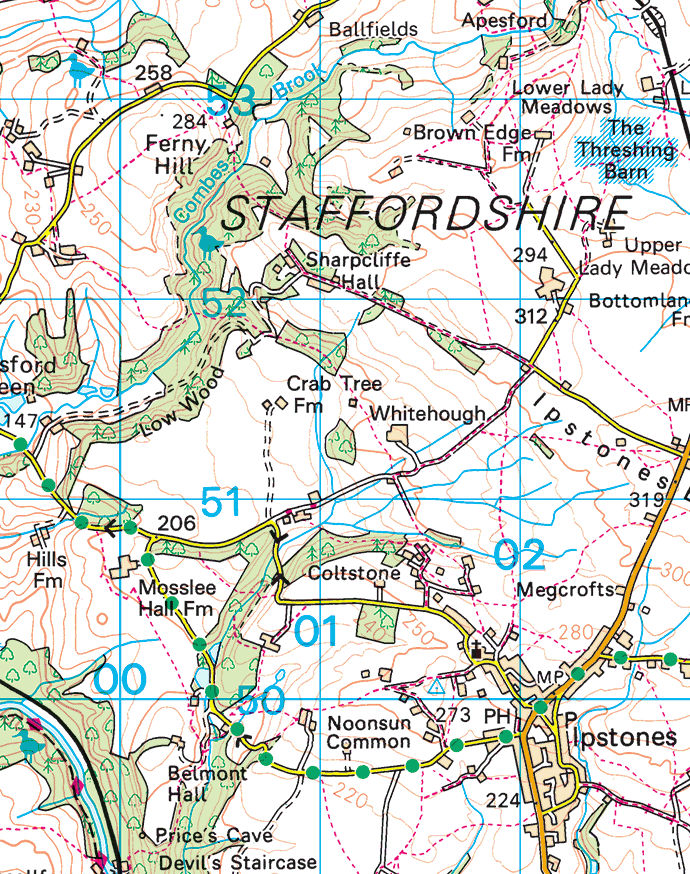

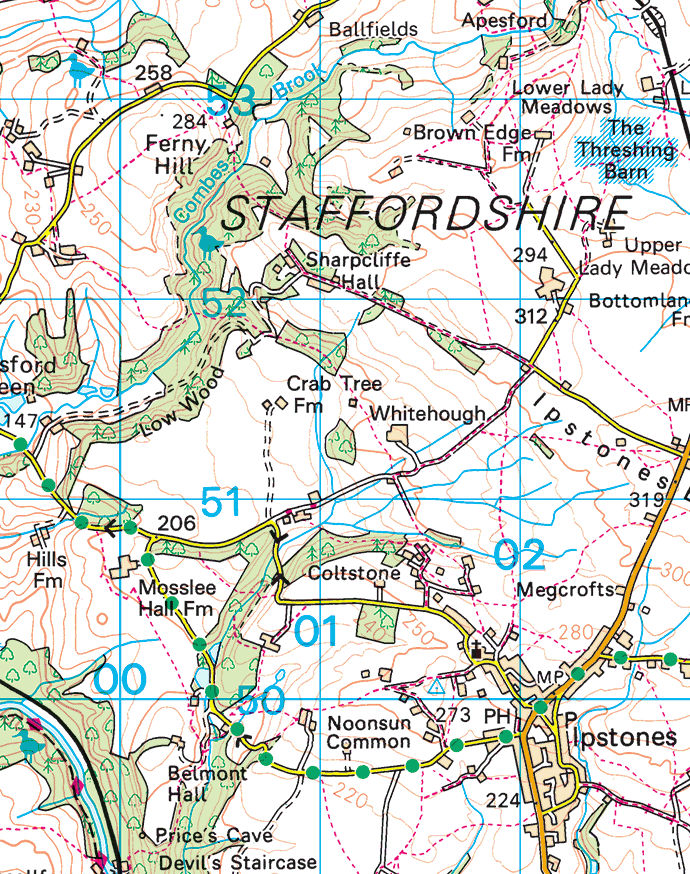

Actually there are two such rocks there, the larger Gog and the smaller Magog. Here are the Gog and Magog rocks marked on the 10:000 OS sheet…

On the larger OS footpath map the two rocks are not marked, but are a short way apart on the slope which sits just slightly west of the map’s big “01” number.

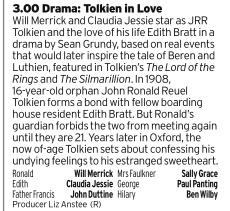

Since the postcards are from perhaps the 1930s, the names must pre-date the ‘ley lines’ era hippies of the late 1960s and 1970s. Pitt (1796) does not use the names, but it would be interesting to know how far back they can be traced.

Since they are on the edge of Ipstones, such stone outcrops may well be the origin of the place-name. Probably meaning simply upland + stones rather than the more romantic notion of imps + stones.

Pitt also has some remarks on the native oatbread (Staffordshire oatcakes)…

“Oat bread is eaten very generally in the Moorlands, and none other kept in country houses; this, however, I cannot consider as any criterion of poverty, or of a backward or unimproved state, as I think it equally wholesome, palatable, and nutritive with [compared with] wheat bread, and little cheaper even here; for upon inquiry at Leek, I found the oatmeal and wheat flour nearly the same price. For several days during my stay in this country, I eat no other bread from choice, preferring it to wheat bread, and rather wonder it is not more general, and kept in London and elsewhere for such palates as prefer it. In the remote country villages it is often baked thick, with sour leaven, and a proportion of oat husks.”

His extended plant-list (at the end of the Appendix) is also annotated with local medicinal and other useful herb-lore. Who knew that English pond-weed could be made into durable writing paper?