A fairly good picture of Stoke’s Lemmy, under ‘Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial’. Might be of use to someone. By TheFearMaster on DeviantArt.

Monthly Archives: August 2018

The North Staffordshire folk-lore of Fletcher Moss

Fletcher Moss, Folk-lore, old customs and tales of my neighbours, 1898.

The author was raised at Standon Hall, some miles west of Newcastle-under-Lyme, to a long-standing local family originally at “Mees Hall, which is in Eccleshall parish, on the

Staffordshire border, near to Standon church and parish.” His book has a wealth of carefully presented folk-lore from Didsbury (for which Stockport was the market town) where he appears to have been first a merchant and then an Alderman (local councillor), and also North Staffordshire where he had grown up and where he still had family. In the book he writes that he often returned to visit Standon Hall, from his new home at Didsbury. The book appears to have been overlooked, previously, as a source for North Staffordshire folk-lore. Here are a few samples, from a rich and long book:

MUMMING:

“The time-honoured custom of mumming or acting plays in our country houses must be referred to, as well as the waits and carol singers, for it is probably the original of our Christmas pantomimes. The mummers, masquers, or guisers go from house to house, demanding admission, and acting a rude play in which St. George fights with the Dragon, alias the Slasher, who is slain and brought to life again by the elixir of life. The most sensible man of the party, who is generally called the fool, goes round with a ladle for a collection, and if contributions are not forthcoming, he gets a broom to sweep the floor and make a dust, saying —

“It’s money I want, and money I crave,

Give me some money, or

I’ll sweep you to your grave.”

He then sweeps towards the fire, and sometimes scatters the ashes as if he were making a raid upon the house fire … A witty actor [among the Mummers] could [also] make many personal and political allusions that were entertaining to the company.”

BREEDING STONES:

There is an almost universal belief among our country folk that stones grow […] I have known several farmers, who were very shrewd, sensible men, who have farmed the same lands and ploughed the same fields all their lives, in some cases for sixty years, and they have said that every year they have had all the loose stones picked by hand off the fields when they have been ploughed and harrowed, and they have been carted away to mend the roads, yet every year there are fresh stones.

The depth of the ploughing has never varied; nothing but farmyard manure has been put on the land; it has never rained anything but rain, hail, or snow; from whence then have come the successive crops of stones?

Adjoining the stackyard at Standon Hall there is a field called the Blakeyard, that has been ploughed every year of this century, and from which hundreds of cartloads of stones have been taken away, and yet it is littered over with stones of every shape and colour, although it has produced a very good crop of oats this last season. We lately searched, and found what the natives call “breeding-stones,” some of which I brought away. They appear to be a rotten or friable granite; and a theory about them is that, being easily broken, they fall into many pieces, and these bits, being left in the soil and turned about by the plough, receive fresh deposits or accretions of mineral matter, and become larger, or, in other words, they grow.

Many farmers will swear that particular stones they have noticed (especially when in water-courses) have grown larger in their recollection.

BEES:

“There is also an ancient belief that bees, although torpid at Christmas, hum a drowsy echo of the angels’ song.” He also makes a passing mention of the ancient custom of ‘telling the bees’ of a recent death in the house.

FOXES:

[At Standon] “the doors of the stables and hen-cotes are adorned with the pads of the fox”, though the reason for this seemingly forgotten. Speculation that it was to ward off evil things.

SPIRITS:

“It is generally believed by our country folk that horses can see spirits or “boggarts” better than men can see them.”

Skulls of ancestors were kept in old halls and also some farms, and the removal of these would bring bad weather.

WEATHER:

“My grandmother Moss [Mees, near Standon, Staffs] used to go in the cellar and cover her head with a silk kerchief if there was a thunderstorm. She thought there was great virtue in the silk, the light bolt would respect it, and “silk was silk in those days,””

“During a time of prolonged wet weather our late rector thought it was time for him to interfere with special prayers for fine weather. When he consulted his wardens, I said I had heard that our neighbours the Methodists had been trying their best for three weeks, but no notice seemed to have been taken of them. He appeared slightly shocked at the comparison, for surely he, with all the authority of the Established Church and the weight of the apostolic succession, would have more influence than they, and it was evidently a case where the prayers were sure to be answered — if they were continued long enough.” [this item is possibly from Didsbury, south Manchester?]

SPRING:

“At pace-egging time [i.e.: the time of egg-and-spoon races] the youth of the villages round about our district [Standon] dressed themselves up with tinsel and finery, and went morris-dancing and partly acting, in the old farm-houses, or on the lawns, or in the servants’ halls of the gentlemen’s houses, the old mummers’ play of St. George and the Dragon. A real horse’s head was got from the neighbouring tan-yard, [tannery] that snapped its jaws (worked by strings) at the legs of the girls, who would scream and want to be taken care of; or a sham horse would be made round a youth who was apparently riding, curveting about, banging others with a bladder, and sometimes called “Tosspot.” The horse was called Old Hob or Old Ball”.

“Easter Monday and Tuesday were called heaving or lifting days, from an old custom of raising or lifting one another on those days, it being another custom that has survived in a wonderful manner. […] On Monday the men lifted the women, and on Tuesday the women lifted the men. Formerly the person operated upon lay down, but in modern times they sat on a chair and were raised up with the chair. There was a well- known character in the corn trade named John Oldham, from Carlton-on-Trent, who was a very big man, his weight being over three hundred pounds. He was too much for the combined strength of all the barmaids in the Spread Eagle Hotel, who made desperate efforts to lift him one Easter Tuesday.”

ROYAL OAK DAY:

“In my boyhood’s days [at Standon] it was considered wicked not to have a bit of oak in one’s cap on Royal Oak Day, and the neglect of it rendered one liable to be pinched, or nettled, or sodded. The horses were decorated with it, and even the church towers all sported their big bough of oak. Every child knew that it was worn to show that the oak was in full leaf on that day, so as to hide the king from the wicked men who wished to kill him.”

(Alan Garner’s memoir “Where Shall We Run To?” confirms this Oak Apple tradition was still alive in his childhood days in nearby Cheshire).

SWOT:

“The word swot or slat means to let fall heavily, to dump down. It is now obsolete; but it was well known to us when children, for my father [at Standon] often used the term “swot it down,”” Obsolete in that sense, but still in use today for giving a heavy thwack to nasty flying insects: e.g. “swot that wasp”. A similar sense also lingers in the modern “swotting” for exams, meaning to take on a heavy load of knowledge in a short period.

HARVEST:

[A place that] has always been a second home to me, is Standon Hall. It is forty miles due south of Didsbury, and near to the main line to London, and yet it is nine miles from any town. I now record the great festival of harvest as it was there kept up, until in our latter days there has ceased to be any wheat harvest to celebrate and rejoice over […] there has not been a grain of wheat or barley grown at Standon Hall for three years. The land has (to use a much misunderstood term) gone out of cultivation. It is now under turf, and worth far more than being under plough, and the great labour difficulty is not with harvestmen, but to get milkmen or milkmaids.

My late uncle […] always treated his men (and every one else) well, and the harvest supper was literally a great feast.

“When the last load [of harvest] was being carted, a great shout of triumph went up for all the neighbours to hear. There are several versions of what was shouted, though I believe the following to be the most proper one: “We’n sheared and shorn, we’n sent the hare to So-and-So’s corn” — mentioning some neighbour who had not finished his harvest.” […] Shouting of “Sickery, sickery shorn, hip, hip hooray,” was loud and continuous as the last load was being carted, and in some districts the last sheaf was dressed up and held in special honour.

Then came the great supper — the feast that was greater even than the Wakes or Christmas. The hall or house-place of Standon Hall is the size of a Cheshire rod — that is, eight yards on every side. At one end of the table were two or three geese, with plenty of sage and onion stuffing ; at another, a huge round of beef, from which could be cut “slices that wouldner bend”; and there were gallons of nut-brown home-brewed ale. Grace was reverently said, and then there was a worrying and gulping of flesh as when a pack of hounds or wolves seize their prey. Then there was plum-pudding and ale, apples and pears and ale, nuts and ale, tobacco and ale, songs and ale, plenty of ale. One man would boast he could teem it down his throat without swallowing ; another, that he would take two dozen glasses right off the reel. Then came the songs, and of these I must only give the first verses :—

“Nimble Ned comes dancing in,

With a jug of ale so brown and prim:

Come, fill your glasses to the brim,

To welcome harvest home, home, home,

To welcome harvest home.”

There was always the well-known John Barley corn, and as the ale was known to have been made from barley grown and malted in the parish, and the mash or worts duly signed with the sign of the cross, the enthusiasm was prodigious; in fact some of the singing resembled bellowing.

The master’s song was :—

“Did you ever see the devil,

With his wooden spade and shovel,

Digging ‘taties by the bushel,

With his tail cocked up ?”

There is a common belief in most countries that a goblin does supernatural work on a farm if well treated and not disturbed. Shakespeare and Milton refer to it. Note also that the spade is wooden. Iron is not liked by demons, it gets too hot.

Another verse of my uncle’s song was :—

“He was dressed in jacket red,

With his breeches of sky blue,

And they had a little hole

Where his teil came through.”

[…] but the [song] that “brought down the house was when the missus came in to sing “She wore a wreath of roses.” That had to be repeated two or three times, till the women mingled their drink with their weeping, for their tears ran down into their ale, and they enjoyed it immensely. Then the women-servants would sing in their turn, generally in a high-pitched quivering falsetto voice :—

“Mark yonder turtle-dove that sits on yonder tree,

He sits and he sings to his favourite she;

Then grant what I ask and believe what I swear,

That a kiss from a maiden’s the ‘batchelder’s ‘ fare”;

or “Gorby Glum” —

“My name is Gorby Glum,

I’m just turned one-and-twenty,

My face, I think, by gum,

Will get me sweethearts plenty.”

Another song was “Sweet William a-mourning amid the green rush.” I could only get one entire verse and the chorus, which I wrote down “phonetically.”

We used to think this chorus was only nonsense, but my recent studies in folk-lore have taught me to find all sorts of meanings in old words and customs, and this also turned out to be an interesting case. The verse was :—

“I’ll sell my locks,

I’ll sell my reel,

I’ll sell my mother’s spinning-wheel,

To buy my love a sword and shiel.

Shule, shule, shule aroon,

Shule gang shoch a locher,

Shog a mocher lu.”

(Chorus repeated.)

The word “shule” sounded Irish [and] I directed the letter to the Professor of Gaelic or Celtic at Owens College. This brought a reply from the Rev. Father Henebry, who sent me a most learned epistle, part of it being in Irish words and letters. He says the original song was probably Irish, translated into English nearly two centuries since, and as the refrain or chorus would lose its timbre in English it was kept Irish. This is very probable, for the word “shule” may be a wailing lament or a stern shout, very much more romantic than the English word “come.” He gives the proper chorus to be :—

[Irish, then the translation] Come, come, come, oh my secret love,

Come quietly, and come silently.

Come quickly and elope with me,

And mayst thou fare unscathed, my love.”

“Fare” is here used in its old sense of travelling; and in the following verse, also supplied by Father Henebry, red is taken as the typical English colour. Mr. Crofton, of Didsbury, has also hunted up and given me another version of the song. It is evidently the passionate lament of an Irish girl for her lover who has emigrated, perhaps to England as a harvester, and the chorus is his call to her to come after him, and the Irish have sung it at our harvest homes until it has been learnt, parrot-like, and the meaning forgotten :—

“I’ll dye my clothes, I’ll dye them red,

Around the world I’ll beg my bread,

Till I find my lover, living or dead.

Shule, shule, shule,” etc.

Imagine these songs being sung with all the wind of men and women who were used to shouting to one another across a forty-acre field; they would have blown the windows out or the roof off a flimsy-built house. After hours of feasting and revelry, the highest happiness of which these peasants could conceive, they would become noisier or drowsier. [Some were got to bed, but]. Others would keep up all night till the broad day-light, and it was time to fetch up the cows and go a-milking.”

BLAZE NIGHT (OLD NEW YEAR):

[At Standon] “The growing wheat was blazed on old Christmas Day, January the sixth being “blaze night,” to scare the witches from the young corn, and ensure good crops for the coming harvest. Men and lads ran all over the wheat with lighted torches of straw, crying out to frighten away all harmful things.”

“The wheat was then sown in autumn, before the full of the moon, and on January 6, as soon as it was dark, all the household, servants, and visitors, took bundles of straw, tied tight like torches, lighted them in the wheat fields, and ran shouting over every bit of ground that had been sown with wheat. This was done to scare the witches from the corn, for, as Shakespeare knew, the witches mildew the young wheat and strike dead the lambs. I believe it was done on that night as being the anniversary of old Christmas, not because it was the Epiphany or Twelfth Day.”

CHESHIRE CHEESE:

The book also has a chapter on the history and folk-lore of Cheshire cheese. Since this is now in the public domain, it might be possible to expand and reformat his text, and accompany it with new illustrations, to make a new small co-authored book.

Hipster teapots of Stoke, circa the 1760s

Fletcher Moss, a new source on North Staffordshire folk-lore

I’m pleased to find a new and previously unknown source on Staffordshire folklore, and it’s a subtantial 330-page book.

Fletcher Moss, Folk-lore, old customs and tales of my neighbours, 1898.

It may have been overlooked by Staffordshire folklorists and bibliographers because the author was located at Didsbury in Cheshire, now swamped as a suburb of south Manchester. Although the author writes that Stockport was the market town for Didsbury (“they knew little or nothing of Manchester” back then, he writes).

More importantly, the preface to his book states that he also draws heavily on the lore of his father’s family in rural north Staffordshire: at Standon Hall (a few miles south-west of Trentham) and Mees [Hall], and Walford (about three miles west of Stone). Standon Hall is also where the author passed his childhood and he frequently returned to visit. It is not to be confused with the rather ugly new Hall built in the village in 1910 and which later became a hospital. The author grew up at what is now Standon Old Hall, which apparently goes back to the 11th century but is seen here after what appears to have been a partial restoration…

But where was “Mees”? The place escapes the modern map makers, but the author elaborates in another book: “My father was born at Mees Hall, which is in Eccleshall parish, on the Staffordshire border, near to Standon church and parish.” So again, near to Trentham and the Potteries.

Possibly the same as what was later known as Meece Old Hall, Ecceleshall.

It looks very promising and I’ll be having a read, and noting any especially nice bits of local folklore. (Update: the information has now been extracted, as “The North Staffordshire folk-lore of Fletcher Moss”).

Moss also produced seven (some say nine) volumes of Pilgrimages to old homes, substantial books containing short accounts of his visits to various antiquarian and architectural gems.

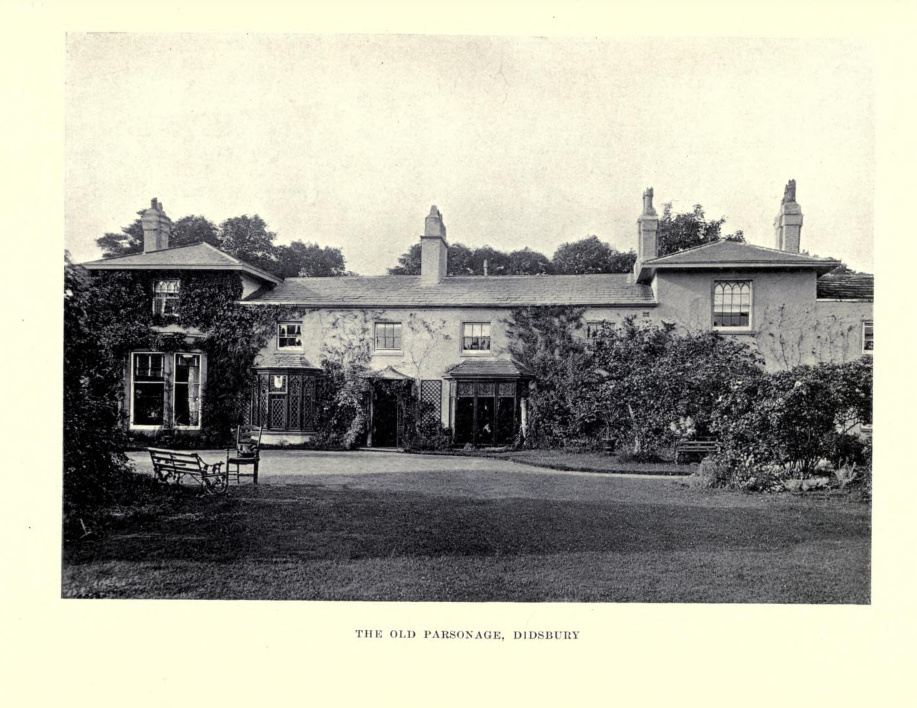

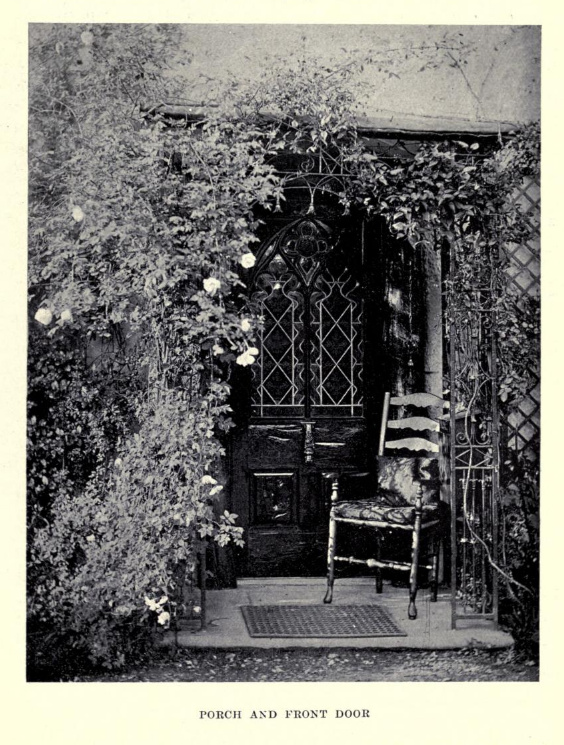

He was such a fine fellow they named the local pub after him, in Didsbury, ‘The Fletcher Moss’. His home environment at Didsbury certain appears to have been conducive to his collecting of folklore…

Regrettably his photographic archive appears to have perished, and the National Archive can only suggest some papers in the Manchester local archives.

Comic Scene

I’m pleased to see there’s now a magazine devoted to celebrating British comics, their makers and publishers. ComicScene UK. The second issue is pre-ordering now.

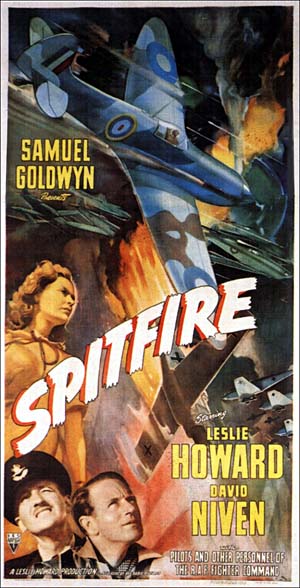

Spitfire (1942)

Free on Archive.org, Spitfire (1942), which was the wartime feature-film story of the life and work of Stoke-on-Trent’s Reginald Mitchell — who designed the Spitfire.

It’s a very grainy and poor copy, presumably dug out of the archive of some U.S. TV station, having fallen into the public domain in the USA. But it’s free. Though know that the USA version was cut down to 90 minutes, while the UK version runs 118 minutes.

If you have some spare cash, there was a Blu-ray disc some years ago, using the movie’s British title The First of the Few, which was “digitally restored” (see above picture) and the full 118 minute version. One buyer on Amazon UK comments “don’t try to save a few quid with the unrestored one. The quality of the picture on the re-mastered edition is superb”.

It seems another good source for a locally-flavoured graphic novel, which could have the first three chapters set in Stoke-on-Trent, and later flashbacks. It would probably have to be a graphic novel, since a straightforward non-political bio-pic movie would be impossible to fund today. It would only get funding if it could be dragged out-of-shape by having various contemporary political angles inserted into it.

Tales from the Past

New to me, the book Tales from the Past: Anecdotes and Incidents of North Staffordshire History (1981), a collection of the first year (1958-59) of articles written for The Sentinel newspaper and drawn from local tales, stories and anecdotes. The weekly series by Tom Byrne continued for a decade, 1958-68.

The book was followed five years later by More Tales from the Past: Anecdotes and Incidents of North Staffordshire History (1986).

Might be good to see a dozen or so tales from these books adapted as a comic-strip anthology.

I’d also wonder if they have any tiny remnants of local pre-industrial folk-lore, sayings or beliefs.

Newcastle as a healthy place in 1903

Entering the public domain in 2019

My quick survey of interesting texts coming out of copyright at the start of 2019, the author having died in 1948. It doesn’t seem to be an especially rich year, in terms of the “big names”.

* Alfred Edward Woodley Mason, author of Fire Over England (a beleaguered Queen Elizabeth I prepares for invasion by the tyrannical Spanish), and The Four Feathers (a filmed war novel). Other historical adventure novels such as The House of the Arrow and The Prisoner in the Opal, plus stories and some non-fiction.

* Montague Summers, a poet who also wrote many non-fiction books on belief in vampires and witches. Also Architecture and the Gothic Novel, and The Gothic Quest: a History of the Gothic Novel.

* Denton Welch, novelist and short story writer who influenced William S. Burroughs.

* W. Paul Cook, friend of H.P. Lovecraft and author of the important memoir In Memoriam: Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

* Samuel Whittell Key, author of a series of stories featuring his ‘occult detective’ character Prof. Arnold Rhymer.

* Guy Ridley, author of the tree-ish fantasy The Word of Teregor (1914).

* Jesse Edward Grinstead, popular writer of a great many Wild West novels.

* Rupert Gould, a cryptozoologist who published popular books such as The Loch Ness Monster and Others, A Book of Marvels, and Oddities: A Book of Unexplained Facts.

* Henry Marten, private tutor of Queen Elizabeth II. His pre-PC The Groundwork of British History (1912) became “one of the most used school textbooks of the first half of the twentieth century”. There was a 1923 edition, possibly simply a reprint. His The New Groundwork Of British History in 1943 updated this standard textbook to 1939 and continued its use in schools into the 1950s. But the 1943 edition was a multi-author work, and thus is presumably not going into the public domain. There was a later reprint in 1964. Various versions including 1943 can be freely found on Archive.org.

* D’arcy Wentworth Thompson, who published an acclaimed translation of Aristotle’s The History of Animals.

* Arthur G. T. Applin. An actor and a ‘name’ in the theatre world, as a writer he seems to have been prolific and with a wide range. An early writer for Mills and Boon, with Chorus Girls (1906) and The Stage Door (1909), but his well-reviewed town novels such as Shop Girls (real-life shop-girls of the 1910s) appears to have upped the tone considerably and somewhat evaded ‘the M&B formula’. Later produced countryside books such as Philandering Angler (memoirs of fishing and philandering), popular mysteries such as Blackthorn Farm, and even The Stories of the Russian Ballet. His later reviews in the 1920s and 30s emphasise his ability churn out swift-paced pulp-ish page-turners, with romantic settings ranging from racecourse to desert.

Also of note is S. J. Simon, a popular British mystery and historical-comedy writer, but only because his novels were written with a fellow writer who didn’t die until 1982. Thus his work is not going into the public domain.

Bill Brandt in Burslem

New picture of the Etruria Woods

Purchasers of my H.G. Wells book may be interested in this good clear (if rather small) picture of the Etruria Woods, albeit as they barely remained in 1964 — as the era of heavy industry entered its final decades and neared its end.

Centre of picture, and in the ravine running off to the left. With what appears to be scrubby moorland to the right indicating more of the struggling remains. The towers are coal-mine winding towers.

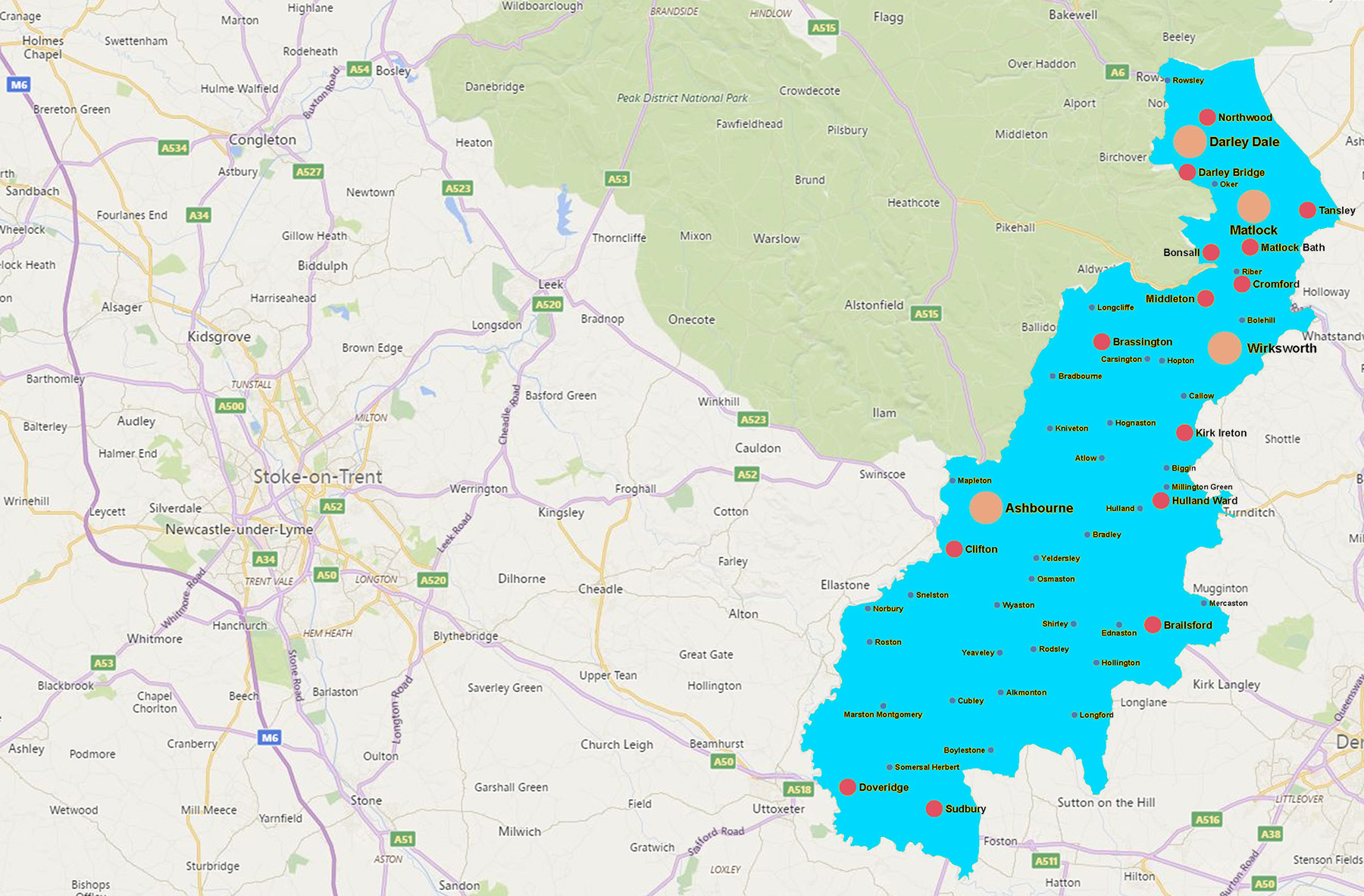

Map of the Derbyshire Dales

I couldn’t find even a half-decent map of the Derbyshire Dales administrative area, via search engines. So I made one. Here it is… extracted from deep inside the local Council’s Local Plan PDF and usefully laid onto a wider map showing its relationship to the Peak District, the Staffordshire Moorlands, and the M6 motorway. As well as nearby Derby there is also a West Coast mainline rail station at Stoke-on-Trent, with fast regular connections to London and Manchester. The local railway station at Uttoxeter will also take you deep into the wilds of the East Midlands and then connect to take you over to the east coast, albeit on a lesser train.

Settlement dot size reflects population size. Green = The Peak District National Park, which the Dales don’t overlap.