Newly online, recordings of Mythmoot V talks, on YouTube. Including an excellent hour with Tom Shippey, “The Hero and the Zeitgeist”. Plus (not on the YouTube playlist) a 90 minute round-table discussion on Tom’s new book, Laughing Shall I Die: Lives and Deaths of the Great Vikings (Reaktion, 2018).

Monthly Archives: July 2018

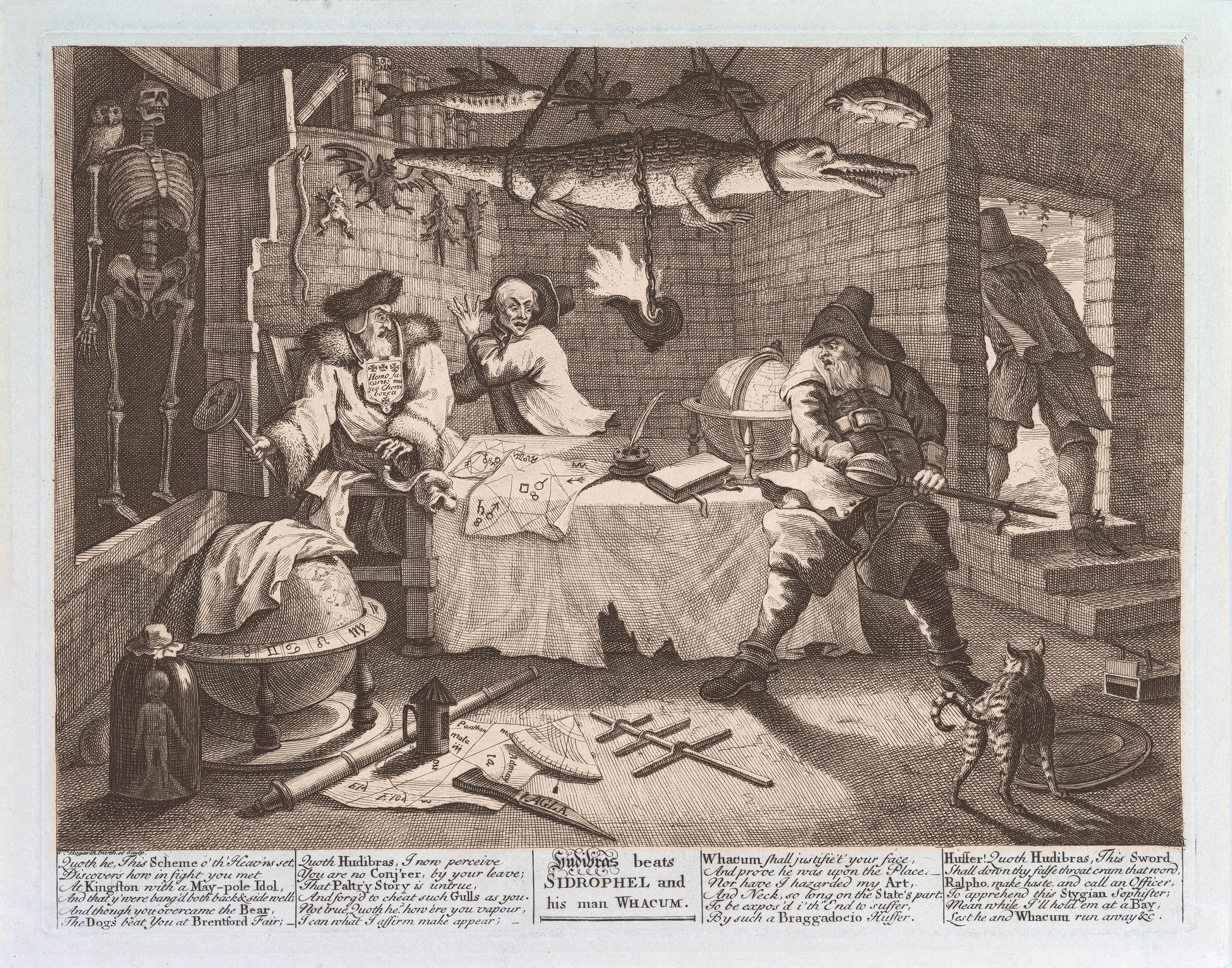

Exposing a fraudulent astrologer, circa the 1670s.

Exposing a fraudulent astrologer in England, circa the 1670s.

The hero Hudibras wants advice on how best to woo a widow, but first he needs to assure himself the astrologer is ‘the real thing’. The astrologer has got some false information about Hudibras, by a roundabout route, and he feeds the information back to Hudibras in the guise of a supposed astrology reading. Thus the hero knows the astrologer to be a fraud. Hudibras holds them at bay with his sword, while his squire goes to fetch a constable. Illustration for Hudibras.

‘Oss shop in Burslem

I’m pleased to see that Burslem now has a horse shop. The Equine Emporium is open now in Queen Street, Burslem.

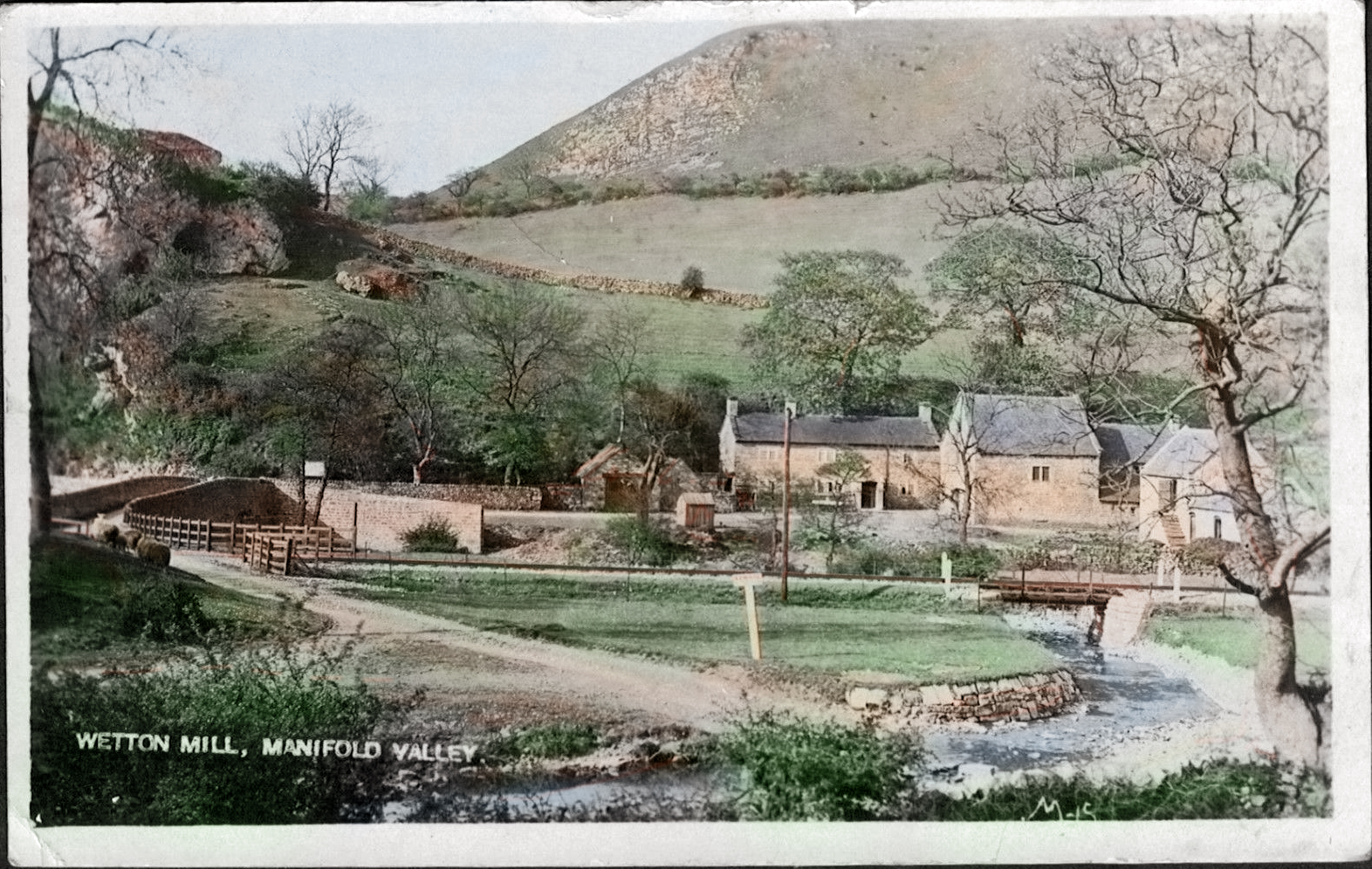

Wetton Mill and Gawain

If you’ve ordered my new book on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, many thanks. The book should have arrived by now. It’s just a side-project from my big Tolkien book, but I hope it’s found interesting. Anyone writing scholarship on Gawain in future will surely need to read it. Below is a bonus colourised picture of the Wetton Mill cave which I didn’t have to hand when making the book. Although the same cave is abundantly illustrated by other pictures in the book, along with some rare ones of its melded companion-in-literature which is located ‘around the corner’ at Redhurst Gorge.

So… I’ve now identified Wells’s original for the character of The Time Traveller in my 2017 book H. G. Wells in the Potteries: North Staffordshire and the genesis of The Time Machine, and a near-perfect local candidate for the writing of Gawain in my 2018 Strange Country: Sir Gawain in the moorlands of North Staffordshire. An investigation. The third and final big ‘Midlands literary mystery’ to crack is earendel and Tolkien, and that’ll be my next book unless I get distracted again. The book is already very well advanced, but with something so huge it needs to be paced properly. I’m considering a two-volume edition.

Uttoxeter to Macclesfield by train

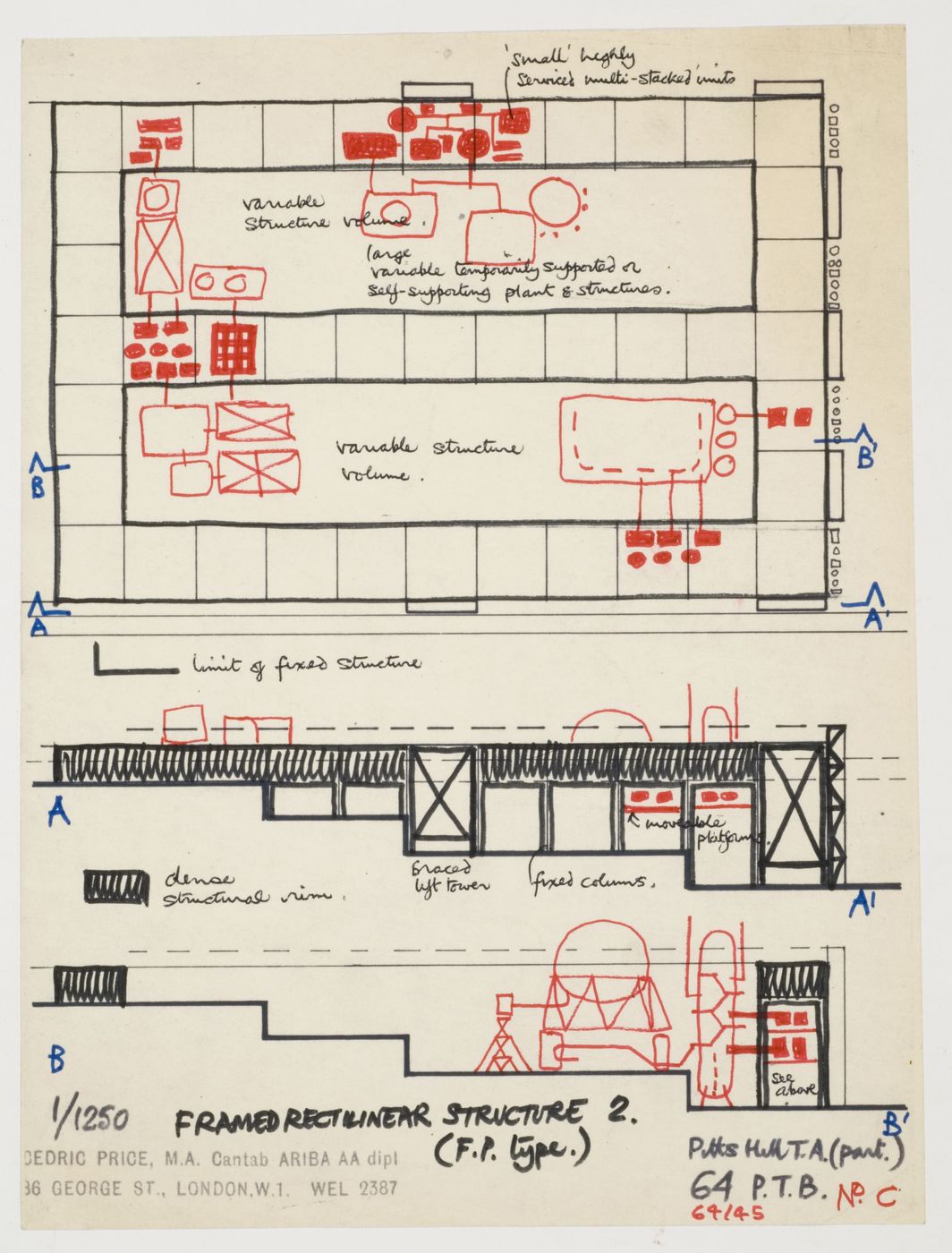

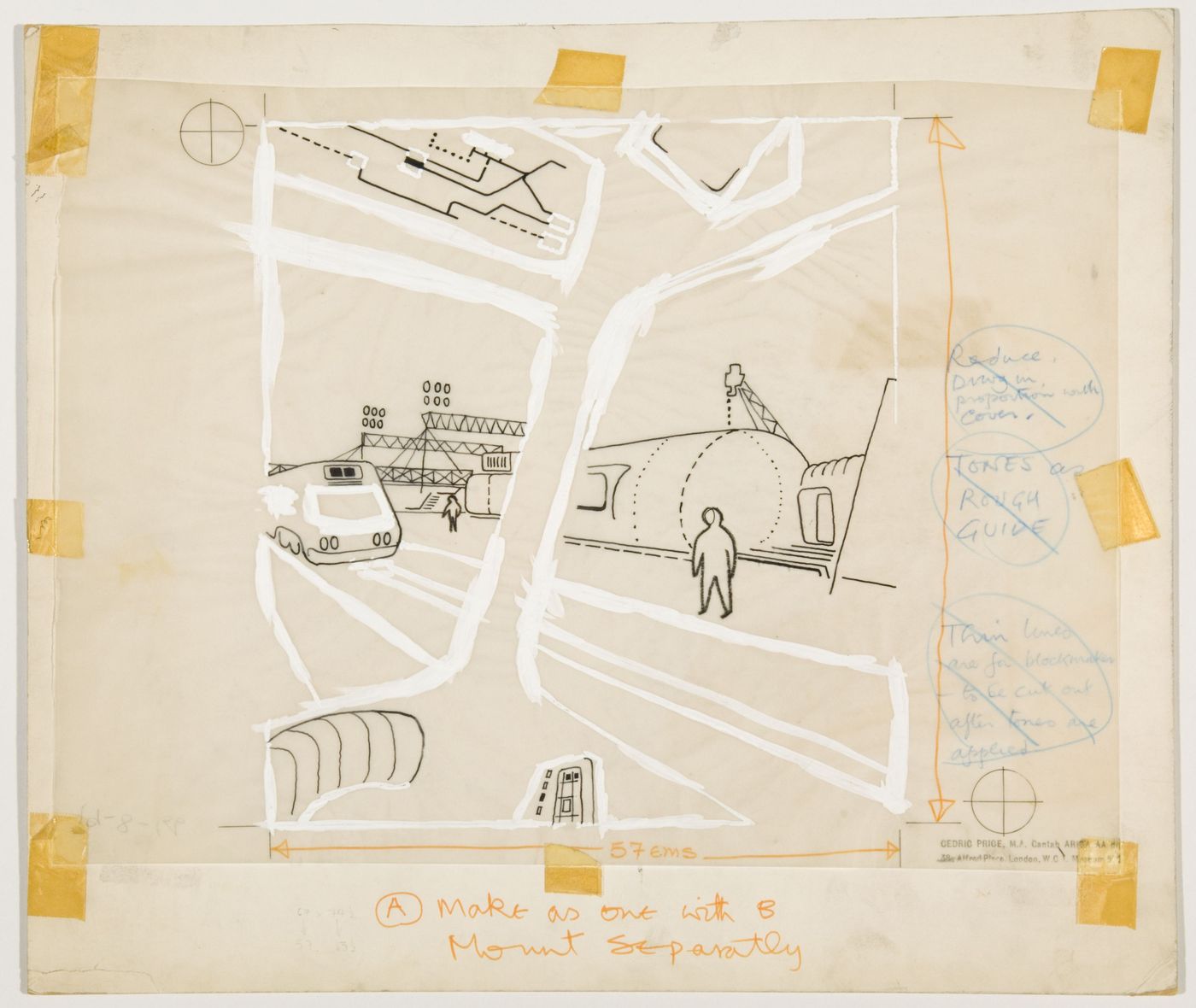

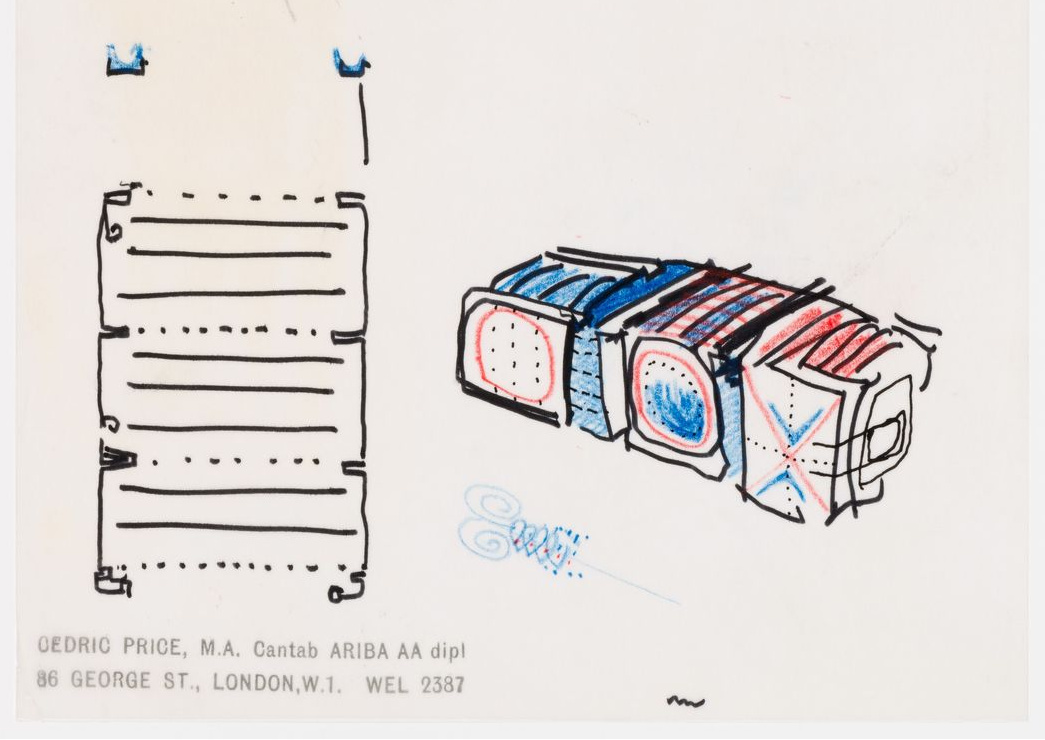

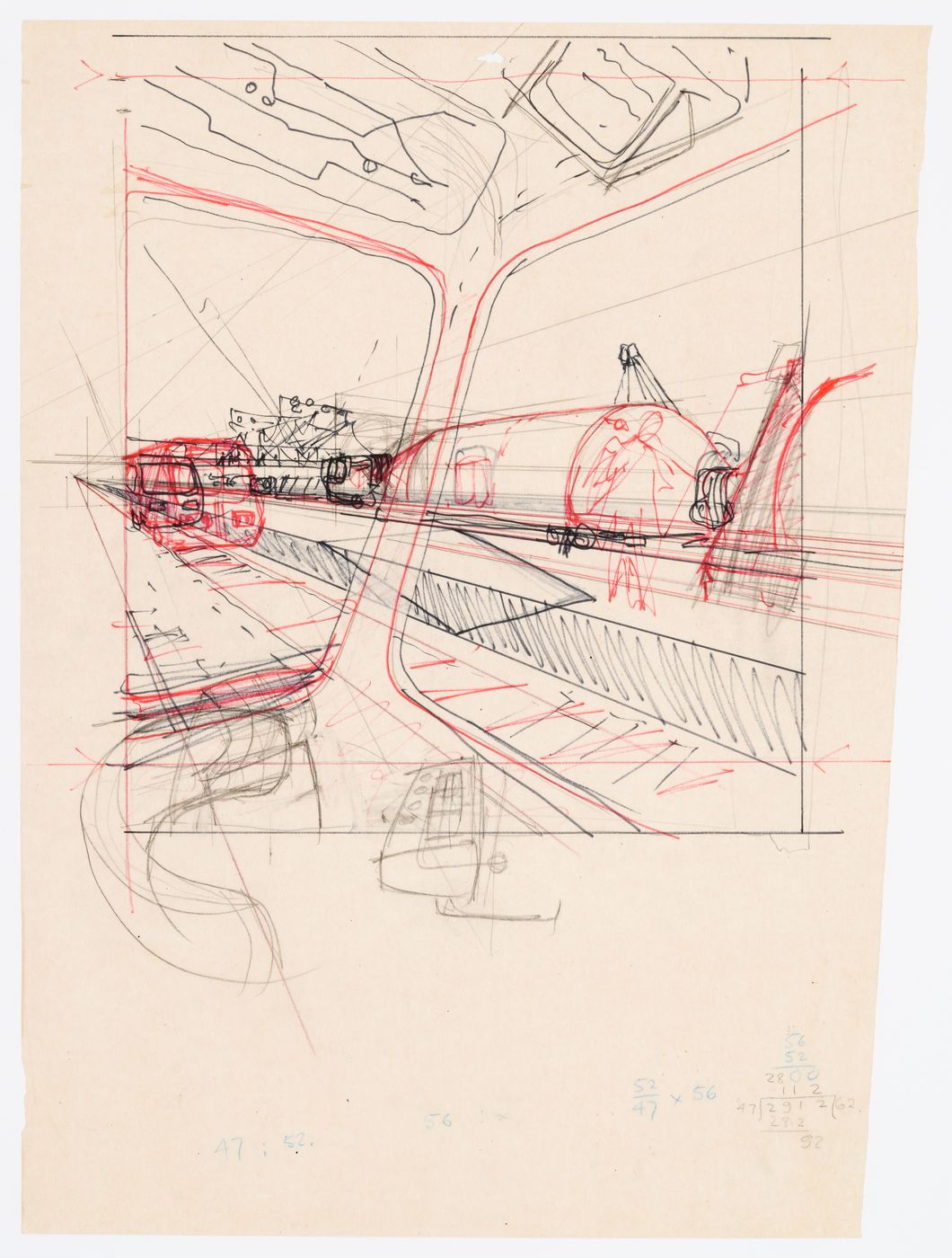

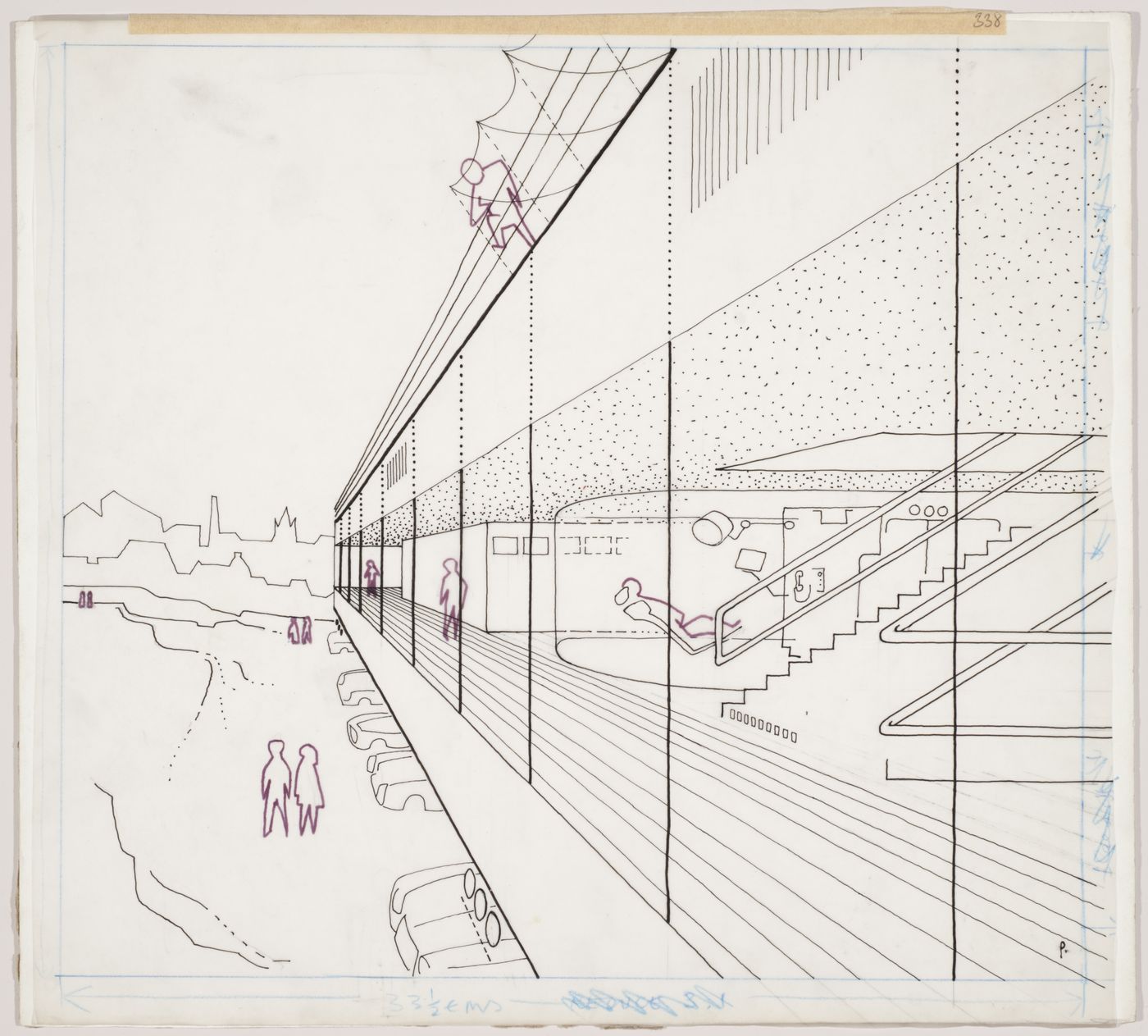

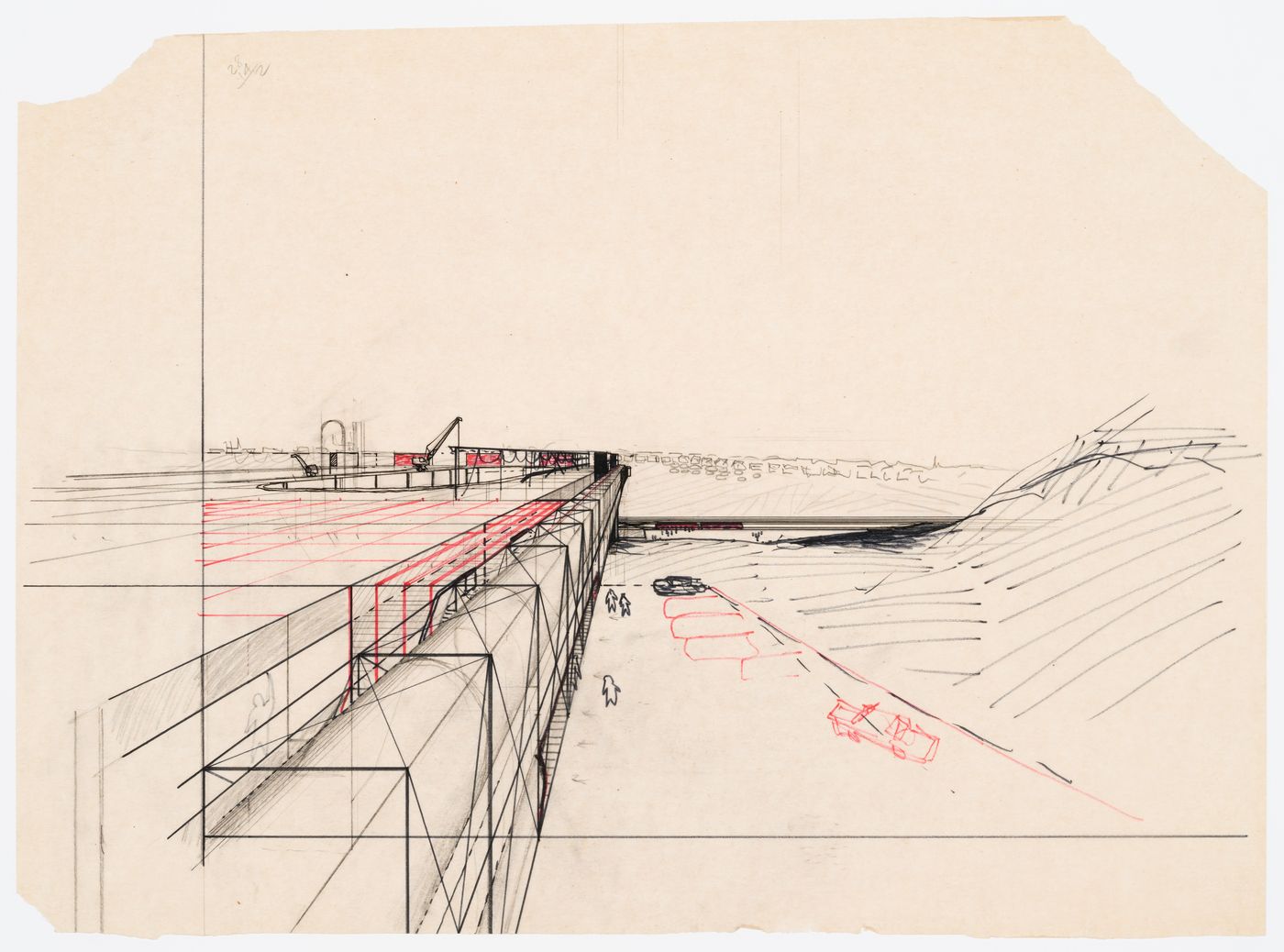

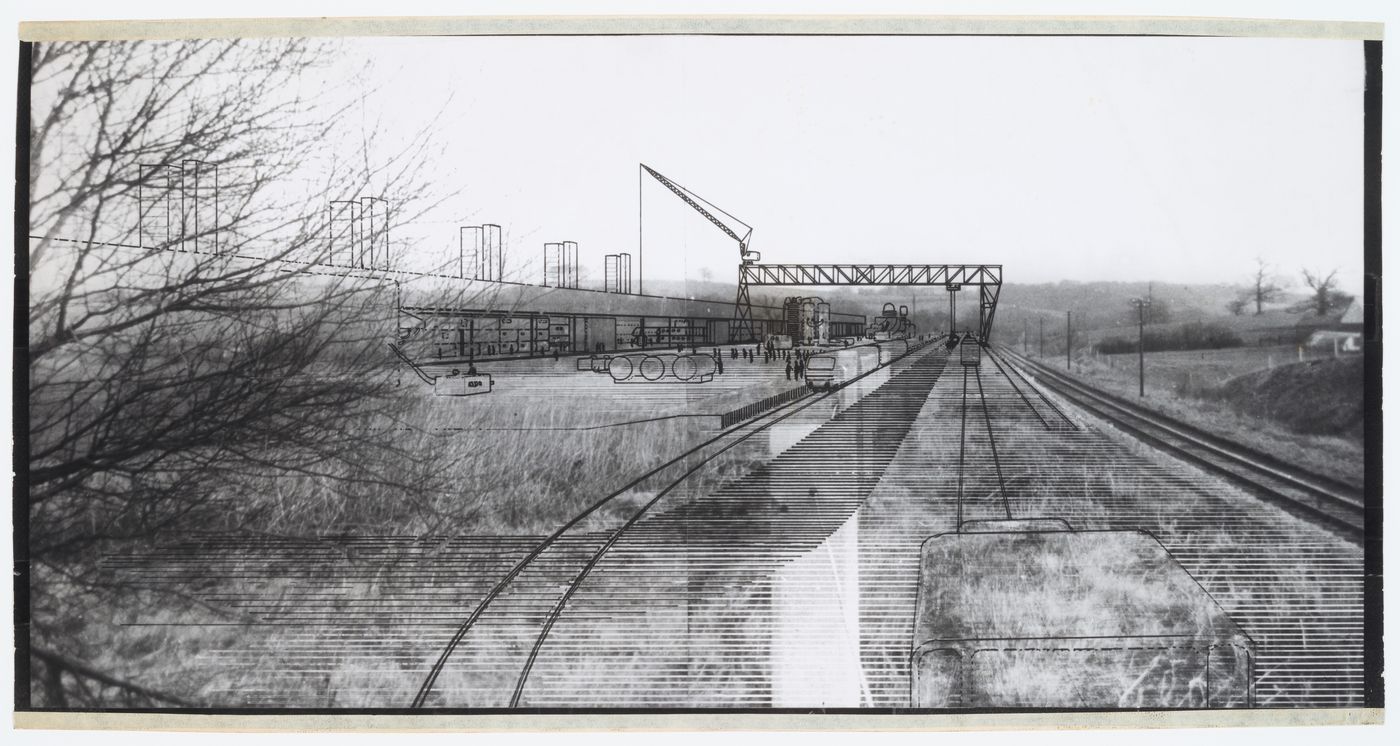

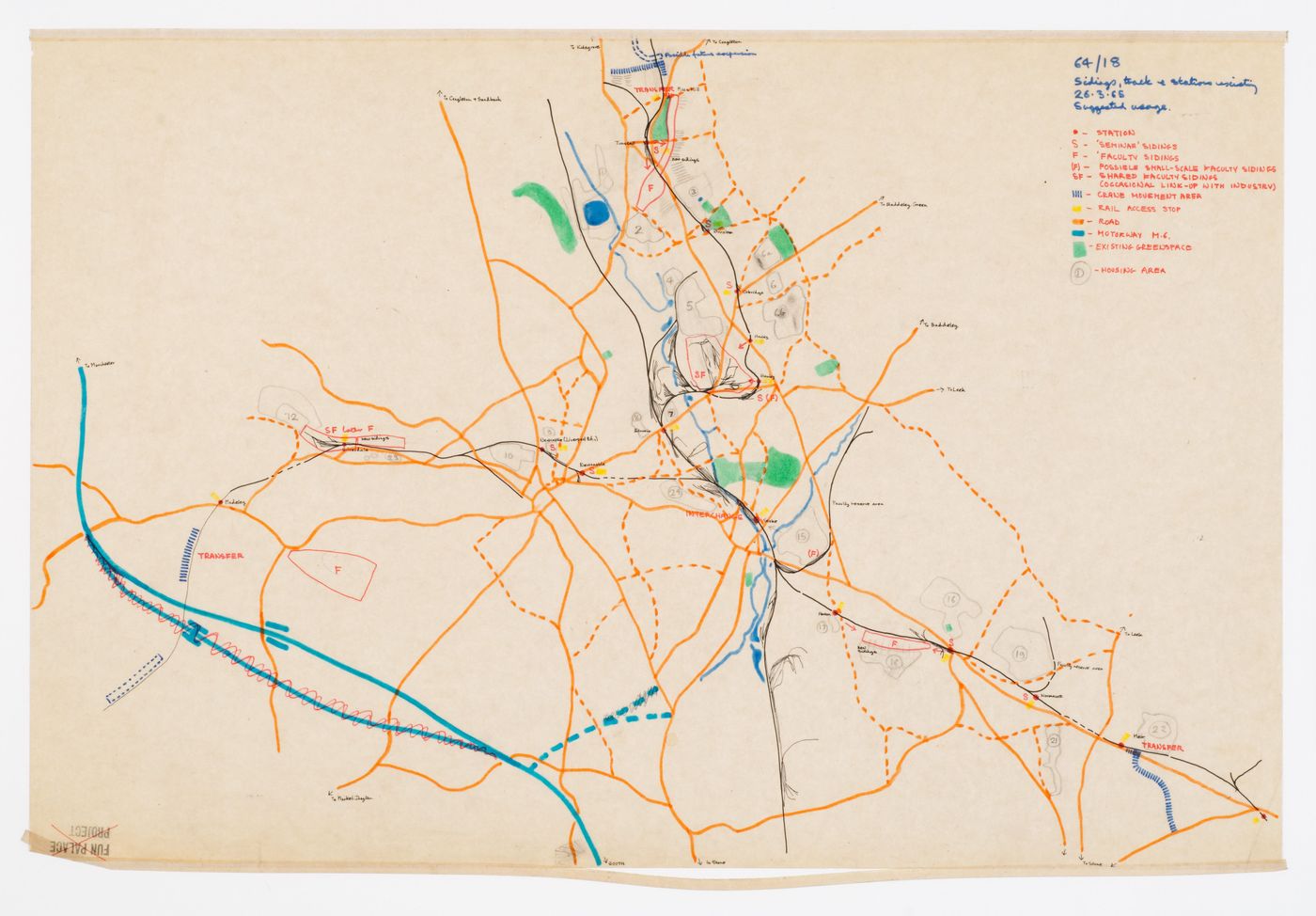

Visualising the ‘Potteries Thinkbelt’ in the mid 1960s.

Below are some of Cedric Price’s conceptual drawings for the £80m “Potteries Thinkbelt” across North Staffordshire, which he proposed in the mid 1960s. The aim was to make some productive use of the old railway lines, then being closed wholesale by Labour’s despised Dr. Beeching. We also had commercial mineral and mining railway lines which were expected to become disused. More widely in the UK, it was imagined from about 1965 that advanced education might be one substitute for declining heavy industry.

While Price had some local connections and thus local knowledge, having been born in Stone and taking his first job in Burslem after leaving school, his plans on returning to the city were almost laughably radical. A sort of ‘travelling university campus’ was proposed. This would have used the former rail lines of the Potteries to provide a new 20,000-student university for North Staffordshire, a place which Price labelled “a disaster area” (New Society, No. 192, 1966). Others thought the same. The Labour government minister Dick Crossman visited Stoke and instantly decided it was a “huge, ghastly conurbation” that should be “evacuated” and not have a penny invested in it. Countless billions, he mused, would never restore the ghastly collection of “slag heaps, pools of water, old potteries, deserted coal mines”. From the 1950s to the 2000s Labour’s doctrine was that of “managed decline”, something that was still having an effect in the city as recently as the brutal mass demolition of Middleport in the 2000s.

But back in the 1960s Price mused that, if the city could not be saved, perhaps the students could. He proposed four types of uber-modern student housing and classrooms-on-rails, all shuttling students of hard science and engineering around the Potteries, inside newly designed rail-car types named ‘Capsule’, ‘Crate’, ‘Battery’ and ‘Sprawl’. These units would be hermetically sealed, with no windows and with artificial atmospheres, to prevent contact with the dismal city outside. Their trains would be serviced from thirty new custom-built railheads and sidings around the Potteries. The structures would “hot-house” students and staff, forcing them into “new living patterns”. Inflatable structures were also rather hazily mentioned, presumably bouncy-castle style entertainment pods.

At the corners of this sprawling ‘rail university’ there would be connection hubs with airports, motorways, mainline rail stations. The humdrum local planners at the City Council would only be permitted to build around the network once everything was in place.

Apparently Price’s proposals were made partly in response to the way in which the leafy new university at Keele had ‘shut itself off’ from the Potteries, and was widely seen as being unconcerned with local people and the needs of the city’s industries. The dispersed nature of the Thinkbelt also fitted nicely into the way that the city council required that all towns be equally serviced, so as not to alienate any voters.

Needless to say, the Thinkbelt was never built. Price departed Stoke for the failing city of Detroit, USA, to propose that their city build a ‘Think Grid’. Stoke’s City Council later dabbled with another ‘grand idea’ proposal, this time around the fledgling 1990s Internet, called WorldGate. That, too, failed to materialise.

Over 30 years later, the Potteries did something rather more sensible with its old mineral railway lines. In opposition to certain rather rotund Councillors who openly claimed that ‘no-one cycles in Stoke, it’s too hilly’, the dynamic new Mayor Mike Wolfe quietly championed bicycle routes. The city successfully paved many of the old rail lines to provide over a hundred miles of off-road bicycle paths (map: North | South). Instead of being imprisoned in sealed pods, the city’s youngsters were to be out in the open air of an increasingly green city.

Further reading:

* An architecture for the new Britain : the social vision of Cedric Price’s Fun Palace and Potteries Thinkbelt, Columbia University PhD thesis, 2003.

* Cedric Price : Potteries Thinkbelt, Routledge, 2007.

* The evolution engine: Organicism, ecology, cybernetics and Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt, Buffalo University PhD thesis, 2012.

* Cedric Price : Works 1952–2003, AA Publications, 2018.

So far as I can tell, the response of the people of the Potteries to such proposals has not been collected.

What Price had to work with. The local rail structure as it existed 1964-65.

What Price had to work with. The local rail structure as it existed 1964-65.

Hunting mountain hare in the Peak

A December ride, hare-hunting with the Buxton and Peak Forest Hunt. By Edward Bradbury, published in his book In the Derbyshire highlands (1881).

“I think the girls have gone mad,” was the Old Lady’s remark as every room at Limecliffe Firs seemed to resound with silvery shouts of “Hark forrard!” “Tally-ho!” “Yoicks!” “Hey, ho, Chevy!” And other exclamations, ecstatic but inexplicable, peculiar to the vocabulary of huntsmen.

It was a December evening preceding a meet of the Buxton and Peak Forest Harriers. The Young Man was to join the hunt. It had also been arranged that the two young ladies and the present writer should drive to the scene of action in the pony carriage.

This had not been settled without some protest from the prudent Old Lady. She remembers the gloom of a certain grey November day in the years agone when the dangers of the chase were personally illustrated at Limecliffe Furs. But a broken limb has not diminished the Young Man’s ardour. It was amusing to hear the animated logic with which he overcame the opposition of the solicitous Mother of the Gracchi. [i.e.: the ideal of the Ancient Roman matron]. His arguments were founded on both moral and physical grounds.

“A run with the harriers” he contended “promotes health, fosters courage, requires judgment, teaches perseverance, develops energy, tries patience, tests temper, and exercises every true virtue. It is recreation to the mind, joy to the spirits, strength to the body. To be a good huntsman was to be a fine manly fellow: a ‘muscular Christian, ‘if you like, but a ‘muscular Christian’ as was Charles Kingsley, the patentee of the phrase. Fishing teaches patience; but just look, my nephew, at the number of moral lessons inculcated by hunting. Care and diligence are required ‘to find’. ‘Look before you leap’ was an aphorism of practical wisdom derived from Nimrod and not Solomon; while ‘Try Back’ was another phrase which might be wisely applied to daily life.

‘Try Back’ when an obstinate hound misleads a pack, and it is found that the trail so diligently sought is hopelessly lost. ‘Try Back’ renews hope and rewards perseverance. ‘Try Back,’ then, in the larger field of life, with its vexations, disappointments, lost chances, and broken hopes. If led into error, ‘Try Back;’ if success is denied thee in that wearisome up-hill toil, ‘Try Back;’ baffled, blighted, broken-on-the-wheel, ‘Try Back.’ Is thy trust betrayed, and thy love false ? Then ‘Try Back.’ There ia a false scent somewhere; a mistake has been made at some critical juncture, so ‘Try Back,’ and a second quest shall give thee splendid recompense.”

There was much more of this eloquent hunting homily, which threw such a glamour of sentiment over hares and horses and harriers that the Old Lady, fond of sermons, gradually relented in her scruples. She finally surrendered when she heard that hunting the hare took precedence of fox hunting, since the fox did not afford half so much genuine sport, and while the flesh of the former was delicious, that of the latter was so much filthy vermin.

I cannot go the length of giving the hunting of the High Peak a place before that of the Quorn Country; but the wild picturesqueness of Derbyshire, with its loose stone walls and steep mountain declivities, imparts a charm and an excitement to the sport which is unknown to the red-coated horsemen of the monotonously flat fields of Leicestershire. The wonder is that Buxton in the winter season does not become as much a hunting centre as Melton Mowbray or Market Harbro’. There are three packs of harriers of established reputation, meeting twice or thrice a week within easy distance of the popular watering place. The Dove Valley Harriers that answer the wild “Tally-Ho!” in the picturesque landscape watered by the Dove. The High Peak Harriers that have their meets either at Parsley Hay, a Wharf on the High Peak line of railway; or Newhaven, a solitary hostelry at the meeting of several roads and a famous house enough in the coaching days; or at Over Haddon, by the Lathkill Dale. And the Buxton and Peak Forest Harriers, which generally start from Peak Forest, or from Dove Holes, and pursue the rough and romantic countryside historically famous as the hunting ground of kings.

It was the latter pack that the Young Man had elected to follow on the morning after that December evening when the house was alive with silvery echoes of the hunting field. The weather had during the past week or two attested that there was something radically wrong with the Zodiac; but on that night, as we looked out from the glow and warmth of the room, the air was keen and clear; the moon shone with an intense white electric light; the roofs glittered in the cold radiance; every detail of architecture was revealed in a sharp relief that made the shadows ebony in their deepness; the gas lamps burned with a dirty yellow; but there was not enough frost to affect the morrow’s enjoyment.

A grey morning follows that glistening night.

“The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve”.

“The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve”.

The mist lies thick upon the hills. The meet is at Dove Holes at twelve; and the Young Man, with the snow of sixty winters in his beard, seems part of his chestnut cob as he rides in black coat, green vest, and corduroys, by the side of our pony carrriage. Raw and cold is the dull ride across Fairfield Common [now on the northern edge of Buxton]; but we have foot warmers in the conveyance, and quite a panoply of soft shawls; while it makes one feel quite snug and warm to contemplate the sealskin of Somebody and the furs of Sweetbriar.

Presently the sun warms the grey fog until the country seems to float in a golden mist; a mellow amber light, such as [the painters] Turner and Claude Lorraine loved to introduce in a poetic atmospheric effect.

There is animation at Dove Holes. A score or more well-mounted horsemen make picturesque patches against the ridges of sombre hills; there are one or two farmers on well ribbed-up horses; there is a lady, well-known to the county as a bold rider, on a sturdy grey mare that is pawing with impatience to charge the stone walls; there is an old gentleman with the gout in a bath-chair, who is anxious to witness the “throw off; ” there are one or two carriages and antiquated gigs; while the number of camp-followers on foot show how potent is the spell of sport among all classes when “the Horn of the Hunter is heard on the Hill.” The keen harriers are with the huntsman, Joe Etchells, the men and boys on foot are grouped around, and take an intelligent interest in the preliminary proceedings. There is the Judge Thurlow look of wisdom on canine countenances, solemn in its sagacity. Presently the Master is seen riding along the road from Buxton, with other well-known members of the Buxton and Peak Forest Hunt. Somebody, who regards everything from what Thackeray called “a paint pot spirit,” [one who thinks in pictures] talks of the hunting groups [in the art of] of Wouvermann, and the horses and hounds of Eosa Bonheur.

Sweetbriar is intently silent : but she makes, nevertheless, a very pretty element in the picture.

And now, behold! The first quest is successful, and cavalry and infantry are instantly scattered in picturesque disorder. It is a picture full of movement; and the broken undulating features of the country, with broad valleys and bold hills, show it up in all its artistic charm. The present hare, however, soon succumbs, and the hounds are thereby “encouraged.” And now the wiry Master of the Pack gives the order for a second quest. The cry comes that another hare has “gone away !” She is in full flight; the alert hounds follow in swift pursuit; this time the chase grows exciting.

People who derive their notion of Puss from Cowper’s hares have an attractive lesson in natural history prepared for them by a hunt with the harriers. [Cowper was a poet who famously reared tame hares]. The celerity of the mountain hare is only exceeded by its subtlety, which exceeds even the cunning of Master Reynard [the fox]. The intellect of the hunter and the instinct of the hounds are taxed to the uttermost by the shifts and doubles and dodges of their ” quarry.” The buck hare, now, after making a turn or two about his “form,” will frequently lead the hunt five or six miles before he will turn his head. But madam is more wily. She delights in harrassing and embarrassing the hounds. She seldom makes out end-ways before her pursuers, but trusts to sagacity rather than speed. See ! Now she is off and the harriers are in hot pursuit. Riders are spurring their horses up the slope. A good run at last, we say. The harriers are well-nigh their prey. Puss sees the intervening distance lessening; for a hare, mark you, like a rabbit, looks behind; and suddenly she throws herself with a jump in a lateral direction and lies motionless. The manoeuvre is a success. The hounds fly past deceived by the diplomatic twist. They pull up at last exasperated.

The scent is lost.

“These ‘ill ‘ares is as fawse as Christians,” says a beefy-faced country man, with steaming breath.

Pedestrians appear to have an advantage over the horsemen. Only at intervals comes the wild and thrilling cross-country “charge of the light brigade,” the spurred galop that belongs to stag or fox-hunting.

The rest is made up of occasional spurts and pauses, for the hare’s flight is made in circles. The infantry can thus keep the cavalry in constant sight. Sometimes, indeed, they have better chances than the mounted Nimrods.

Another “find.” The harriers are now “getting down” to the deceptive turnings of Puss. The wild rush clearly won’t do, they intuitively argue; and so with strange intelligence they resolve to keep themselves in head, and, with nose to ground, determine to checkmate the craft of the game with a responsive craft. They take the trail up with intellectual sagacity. Finding her “doublings” of little use now, Puss makes across a turnip field for the hill.

“She’s for Peak Forest or Sparrow Pit !” is the cry of the crowd. The pack plod up hill. “Hark to Watchman !” “Follow Watchman !” is the hurried command. The lady of the hunt is now neatly leading. Esau follows. The young man is showing his sturdy back to a field of flagging horses. A narrow stream, tumbling between steep banks over rocky boulders, presents itself. Some of the horsemen seek an easier avenue. One, more adventurous, who rides in a long mackintosh coat, takes a “header” in the water. He scrambles out soaked to the skin. “A good job tha ‘ browt thi ‘ macintosh wi ‘ thee!” Says a consoling country friend to the dripping rider as he seeks the bank of the stream.

It is “bellows to mend” before the steep stony summit of Beelow is reached. We can see the white steam from the horses ‘ nostrils. The hare, being able to run faster up hill than down, has the pull over horse and hound. Before the top of the stubborn hill is gained, however, she has a premonition of danger ahead. A sudden turn; and she bounds through a flock of sheep and under the very legs of the horses toiling up the ungrateful ascent. The hounds turn and tear down after the scent in relentless pursuit. A stout farmer comes a crucial cropper over a stone wall. Half of the loose limestone boulders fall over him. ” Oh! Is he hurt?” demands Somebody with startled solicitude, while horse and rider lie together. “Noa, not ‘im; he’s non hurt; ha fell on ‘is yed,” says a sympathetic yeoman at the post of our observation.

Now puss takes the wall, and passes down the road. She skirts the very wheels of our carriage.

We see her startled brown eyes, the long hair about the quivering mouth, the beautiful silky ears thrown back in an agony of strained alertness; the soft colour of her winter fur. Fly past the dogs. Come the hunters. Boys on foot beat galloping horses in their fleetness. There is a wild clamour as the pack pelter down hill. It is irresistible. The excitement is intoxicating. Somebody and Sweetbriar are racing after the pursuers. Even the gouty old gentleman in the bath-chair gets out and hobbles along as if he had lost his head. A woman from a cottage close by rushes out with a frying pan in her hand; among the crowd is a village bootmaker, with his hat off and his apron on. I have known staid tradesmen on similar occasions also take to flight at the thrill of the clear “Tally-ho !” Men, mark you, who are as sedate and phlegmatic as Dutchmen under any other circumstances, and never knew a faster pulse of life.

Lo! The hare doubles again; but the harriers are upon her. We are close by at the finish. Poor Puss utters a death-cry, piercing in its helpless pathos. It is like the sobbing appeal of a child.

Sweetbriar begs for the doomed life to be saved; and the exasperated harriers, eager for blood, are driven off, so that she may have the beautifully shaded coat. But the timid creature is dead, and the frightened eyes are glazed.

When the hunters get together in close company, there are one or two black coats, green vests, and corduroys that are dabbed in dirt, and nearly every horse is blowing, after the sharp burst over the hilly country. Refreshment is in demand at a roadside tavern. The beverage most in favour is a curious alcoholic mixture, very popular among Derbyshire huntsmen, and known as “thunder-and-lightning.”

It is composed of hot old ale, ginger, sugar, nutmeg, and gin. On paper this appears a dreadful draught, worthy of Lucrezia Borgia [a famous poisoner]; but the eagerness with which it is quaffed this December afternoon is practical proof of the inspiring effect of the stirrup-cup on the exhausted Actaeons of the Peak [reference to the mythical hunter of Ancient Greece].

This is the last run of the day, for the short-lived sun is setting in red behind the moorland edges, and the amber mist is deepening into fog. We drive home in the waning light, exhilarated with the stirring incidents of the day. The young Man has much to tell us, as he ambles along by our side, of spirited passages in the hunt which had escaped us, and which sound like an Iliad to our ears.

At Limecliffe Firs to-night we discuss at supper the plump hare of the hunt, whose pitiful cry of pain we heard as it died. And we find that the healthful air, the joyous freedom, the excitement and the exercise of the day, have made us too grossly gastronomical to feel sentimental over devouring our victim.

But why is Sweetbriar absent from the table ?

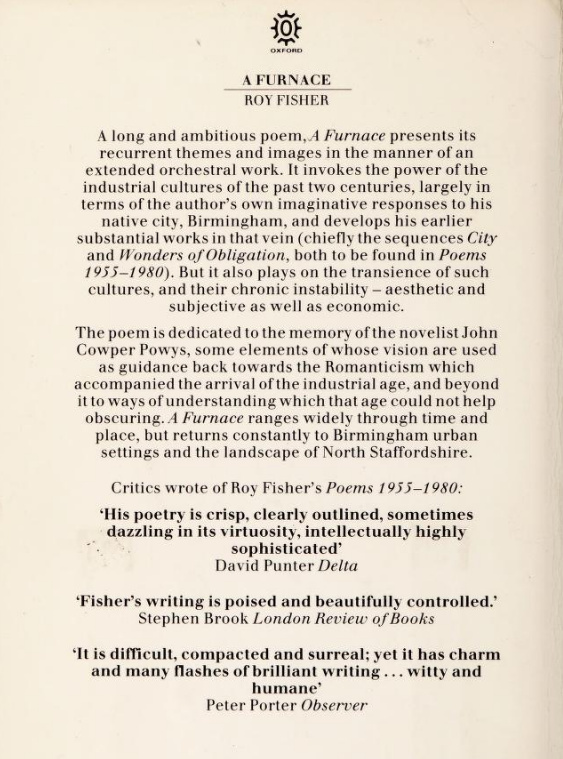

Roy Fisher as a poet of the Staffordshire Moorlands

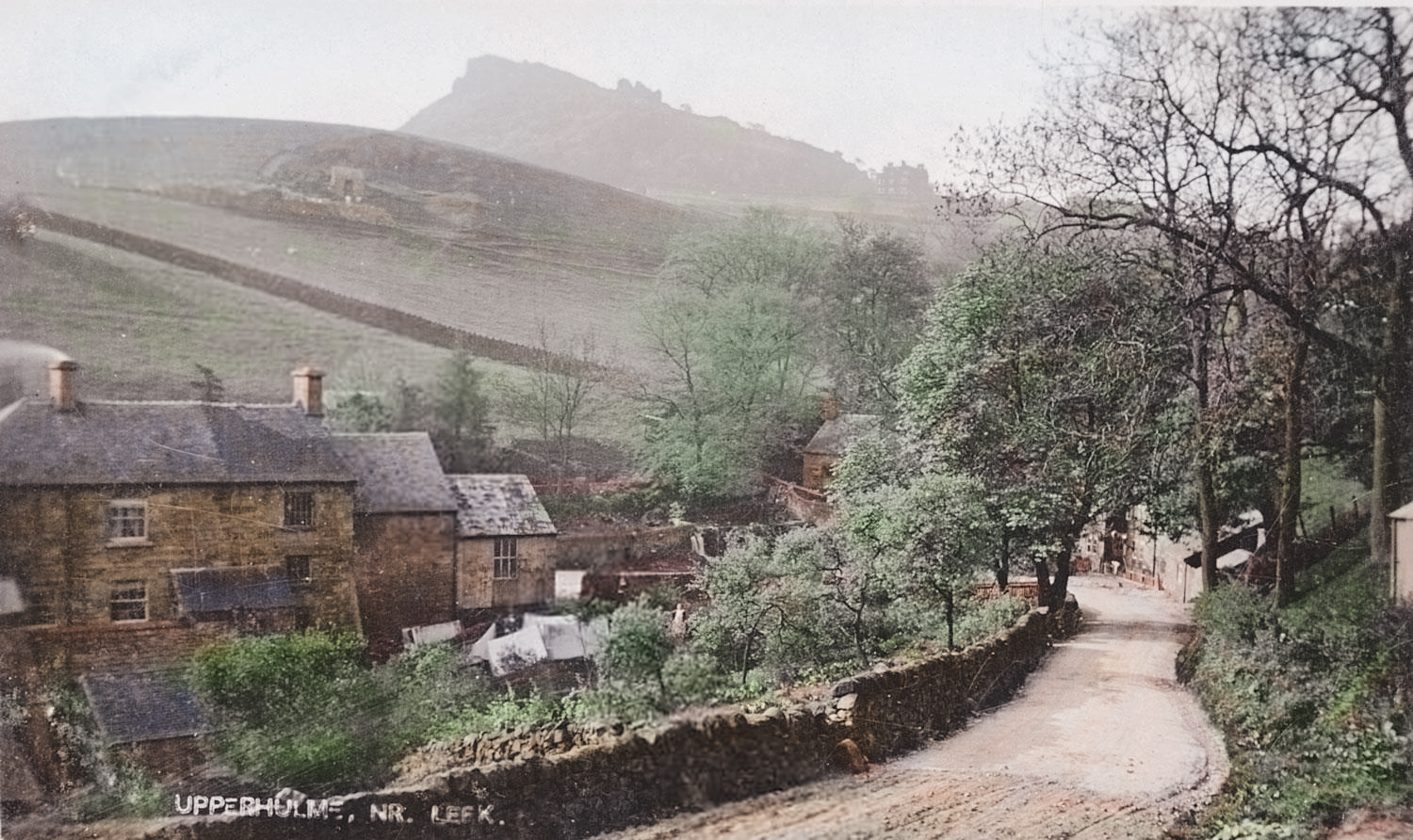

I’d always thought of Roy Fisher as a Birmingham poet. But the back-cover blurb for his book A furnace (1986) remarks that he “returns constantly to Birmingham urban settings and the landscape of North Staffordshire.” How so? His Introduction to the book reveals he had moved away to live in the “northern tip” of Staffordshire. Seemingly around the Roaches, judging by the poems (“Coming home by the road across Blackshaw Moor …”).

A furnace may interest those seeking good poetry about the Moorlands, and I’m guessing that there may be other Moorlands topographical poems by Fisher to be found. Apparently his 2011 Bloodaxe collection Standard Midland… was (according to the blurb writers) heavily “concerned with landscapes, experienced, imagined or painted, particularly the scarred and beautiful North Midlands landscape in which he has lived for nearly thirty years.” “North Midlands” is impossibly vague publisher-ese, designed to appeal to as wide a set of buyers as possible. But Wikipedia clarifies: “Fisher moved to Upper Hulme, Staffordshire Moorlands in 1982, and to Earl Sterndale in Derbyshire [the Peak, near Buxton] in 1986”. Thus it seems probable that the Roaches and district may only have had a four-year poetic consideration in terms of being a ‘home place’.

Still, a major book obviously came out of that time and place, A furnace. It spirals between north Birmingham and the Moorlands of North Staffordshire. Interesting to see that Fisher noticed how the old country ways lingered on, in A furnace, even in what (even then) was horribly urban north Birmingham. On glimpsing an old woman sitting in the sun up an entryway, still dressed like a country peasant in the 1970s or early 80s…

this peasant

in English, city born; it’s the last

quarter of the twentieth century

up an entryway

in Perry Barr

I think that was one of the things I always liked about north Birmingham, there was always the sense that the countryside was lingering in both the people and in neglected corners. Or, in the case of Sutton Park, that it had never departed and could only be nibbled at (usually by corrupt council officials taking chunks for new housing estates).

It can be had on the Amazon Kindle for £8.50, along with most of Standard Midland, in the second expanded edition of his The Long and the Short of It: Poems 1955-2010 (2014).

Tolkien’s Published Art – new list

A handy new list of Tolkien’s Published Art, which is a newly-revised update of the art section to be found in J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Reader’s Guide (2017 edition). It’s kindly been placed online for free by the authors, in PDF.

Incidentally, I see that I previously wrongly called the Companion and Guide a third edition, in a previous and hasty “oh, gosh look!” blog post. It’s actually the second edition, and my error here has been corrected.

A Creeping Thing

Newly released PhD, ‘A Creeping Thing’: the Motif of the Serpent in Anglo-Saxon England (2017).

“This thesis aims to survey and interpret the symbolic role of the serpent in a number of different, clearly defined contexts and look for common associations and continuities between them. In finding these continuities, it will propose a underlying, fundamental symbolic meaning for the image of the serpent in Anglo-Saxon England.”

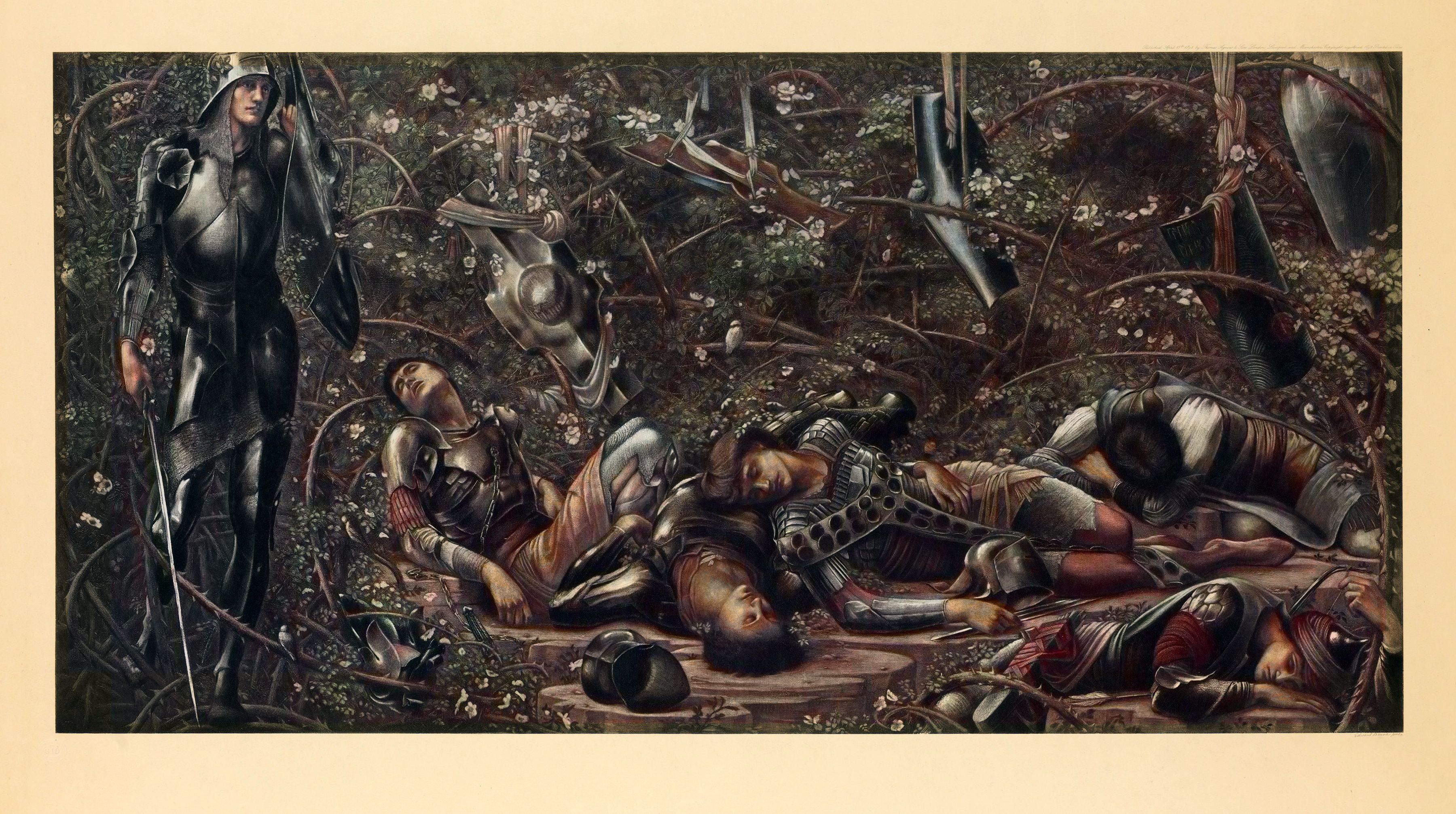

‘Burne-Jones: Pre-Raphaelite Visionary’

A Peep at the Potteries, 1839

An account of the Staffordshire Potteries, November 1839. Reprinted in the British Colonial Magazine. The anonymous author appears to be making a return visit after 20 years, and one suspects he was someone raised in the district and who left it circa 1819. This is because he walks the back-paths and by-ways, going thus from Longton to Burslem with some confidence.

A PEEP AT THE STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERIES.

… There are few that have any accurate or lively idea of that singular district which furnishes us with the earthenware we are daily using, from the common flower-pot to the most superb table service of porcelain, from the child’s plaything of a deer or a lamb resting under a highly verdurous crockery tree, to the richest ornaments for the mantlepiece, or chaste and beautiful copies of the Portland or Barberini vase. Who has a knowledge of this district? Who is aware that it covers with its houses and its factories a tract of ten miles in length, three or four in width, and that in it a population of upwards of 70,000 persons is totally engaged iu making pots, that cooks and scullions all over the world may enjoy the breaking of them? Such, however, is the reputed extent and population of the Staffordshire Potteries.

[…] to those who travel through it by night [by train], it presents a remarkable appearance. The whole region appears one of mingled light and darkness. Lights are seen scattered all over a great extent in every direction — some burning steadily, others huge flitting flames, as if vomited from the numerous mouths of furnaces or pits on fire. Some are far below you, some glare aloft as in mountainous holds. The darkness exaggerates the apparent heights and depths at which these flames appear, and you imagine yourself in a much more rugged and wild region than you really are.

Daylight undeceives you in this respect, but yet reveals scenery that to the greater number of passengers is strange and new. They see a country which in its natural features is pleasing, bold to a certain degree, and picturesque to a still greater. There is the infant Trent, a small stream winding down from its source in the moorlands towards the lovely grounds of Trentham, the seat of the Duke of Sutherland, through a fine expanded and winding valley, beyond which rises the heathy heads of moorland hills towards Leek. Among and between the pottery towns are scattered well-cultivated fields, and the houses of wealthy potters, in sweet situations, and enveloped in noble trees; but the towns themselves are strange enough.

[When walking …] In the outskirts, and particularly about Lane-End [Longton], you find an odd jumble of houses, gardens, yards, heaps of cinders and scoria from the works, clay-pits, clay-heaps, roads made of broken pots, blacking and soda-water bottles that perished prematurely, not being able to bear “the furnace of affliction,” and so are cast out “to be trodden under the foot of man;” garden walls partly raised of banks of black earth crumbling down again, partly an attempt at a post-and-rail, with some dead gorse thrust under it; but more especially by piles of seggars — that is, a yellowish sort of stone pot, having much the aspect of a bushel measure, in which they bake their pottery ware. Many of these seggars are piled up also into walls of sheds and pig-sties. The prospects which you get as you march along, particularly between one town and another, consists chiefly of coal-pits and huge steam engines to clear them of water, clay-pits, brick yards, ironstone mines, and new roads making and hollows levelling with the inexhaustible material of the place, fragments of stoneware.

As you proceed [through Longton], you find in the dirtiest places, troops of dirty children, and, if it be during working hours, you will see few people besides. You pass large factory after factory, which are general round a quadrangle with a great archway of approach for people and waggons. You see a chaos of crates and casks in the quadrangle ; and in the windows of the factory next the street earthenware of all sorts piled up, cups, saucers, mugs, jugs, teapots, mustard-pots, inkstands, pyramids and basins, painted dishes and beautifully enamelled china dishes and covers, and, ever and anon, a giant jug, filling half a window with its bulk, and fit only to hold the beer of a Brobdignag monarch [a giant]. In smaller factories, and house-windows, you see similar displays of wares of a common stamp ; copper-lustre jugs and tea-things, as they call them, of tawdry coloring and coarse quality, and heaps of figures of dogs, cats, mice, men, sheep, goats, horses, cows, &c.,&c, all painted in flaring tints laid plentifully on; painted pot marbles, and drinking-mugs for Anne, Charlotte and William, with their names upon them in letters of pink or purple, or, where the mugs are of porcelain, in letters of gold.

While you are thus advancing and making your observations, you will generally find your feet on a good footpath, paved with the flat side of a darkish sort of brick; but, ever and anon, you will also find your soles crunching and grinding on others, composed of the fragments of cockspurs, stilts and triangles, or, in other words, of little white sticks of pot, which they put between their wares in the furnace, to prevent them from running together. You pass the large and handsome mansions of master potters, standing amid the ocean of dwellings of their workmen. You meet huge barrels on wheels, white with the overflowing of their contents, which is ‘slip’, or the material for earthenware in a liquid state as it comes from the mills where it is ground; and at the hour of leaving the factories for meals, or for the night, out pour and swarm about you, men in long white aprons, all whitened themselves as if they had been working among pipe-clay, young women in troops, and boys without number. All this time imagine yourself walking beneath great clouds of smoke, and breathing various vapours of arsenic, muriatic acid, sulphur, and spirits of tar, and you will have some taste and smell, as well as view of the Potteries; and, notwithstanding all which, they are as healthy as any manufacturing district whatever.

Such is a tolerable picture of the external aspect of the Potteries, but it would be very imperfect still, if we did not point out all the large chapels that are scattered throughout the whole region, and the plastering of huge placard on placard on almost every blank wall, and at every street corner, giving you notice of plays and horse riders, and raffles! No: but of sermons upon sermons; sermons here, sermons there, sermons every where! There are sermons for the opening of schools and chapels, sermons for aiding the infirmary, for Sunday schools and infant schools, announcements of missionary meetings and temperance meetings, and perhaps, for political meetings also, for it is difficult to say whether the spirit of religion or politics flourishes most in the district.

The Potteries are, in fact, one stronghold of dissent and democracy. Nine-tenths of the population are dissenters. The towns have sprung up rapidly, and, comparatively, in a few years, and the inhabitants naturally associate themselves with popular opinions both in government and religion. They do not belong to the ancient times, nor therefore the ancient order of things. They seem to have as little natural alliance with aristocratic interest and establishments of religion as America itself.

“This people … seem to have sprung out of the ground on which they tread, and claim as much right to mould their own opinions as to mould their own pottery.”

This people, indeed, are a busy swarm, that seem to have sprung out of the ground on which they tread, and claim as much right to mould their own opinions as to mould their own pottery. The men have been always noted for the freedom of their opinions, as well as for the roughness of their manners. But in this latter respect they are daily improving, Nearly twenty years ago, we have seen some things there which made us stare. We have seen a whole mob, men, women and children, collect round a couple of young Quaker ladies, and follow them along the streets in perfect wonder at their costume; and we have seen a great potter walk through a group of ladies on the footpath, in his white apron and dusty clothes, instead of stepping off the path; and all that with the most perfect air of innocent simplicity, as if it were the most proper and polite thing in the world. We also remarked that scarcely a dog was kept by the workmen but it was a bull-dog; a pretty clear indication of their prevailing tastes. But their chapels and schools, temperance societies, and literary societies, and mechanics’ institutes, have produced their natural effects, and there is now reason to believe that the population of the Potteries is not behind the population of other manufacturing districts in manners or morals.

Were it otherwise, indeed, a world of social and religious exertion would have been made in vain. It is not to be supposed that such men as the Wedgwoods, the Spodes, the Ridgways, the Meighs, &c. &c, men who have not only acquired princely fortunes there, but have labored to diffuse the influence of their intelligence and good taste around them with indefatigable activity, should have worked to no purpose. Nay, the air of growing cleanliness and comfort, the increase of more elegant shops, of banks and covered markets, are of themselves evidence of increased refinement, and therefore of knowledge. One proof of the growth of knowledge we could not help smiling at the other day. We had noticed some years ago that a public-house with the sign of a leopard was always called the Spotted Cat; nobody knew it by any other name; but, now, such is the advance of natural history, that, as if to eradicate the name of Spotted Cat forever, the figure of the beast is dashed out by the painter’s brush, and the words, The Leopard, painted in large letters in its stead. [The Leopard, in Burslem? Most likely the destination of his walk from Longton to Burslem.]

[Details of the Methodists and their influence on local Biblical names] If the potters have been fond of ancient and patriarchal [personal] names, they have been equally fond of modern improvements and discoveries in their art; and when we recollect that little more than a century ago the Potteries were mere villages, their wares rude, their names almost unknown in the country, and now behold the beauty and variety of their articles, which they send to every part of the world, not excepting China itself; when we see the vast population here employed and maintained in comfort, the wealth which has been accumulated, and the noble warehouses full of earthenware of every description, we must feel that there is no part of England in which the spirit and enterprise of the nation have been more conspicuous.