Update: An updated, expanded and peer-reviewed version of this appeared in the journal Penumbra in 2022.

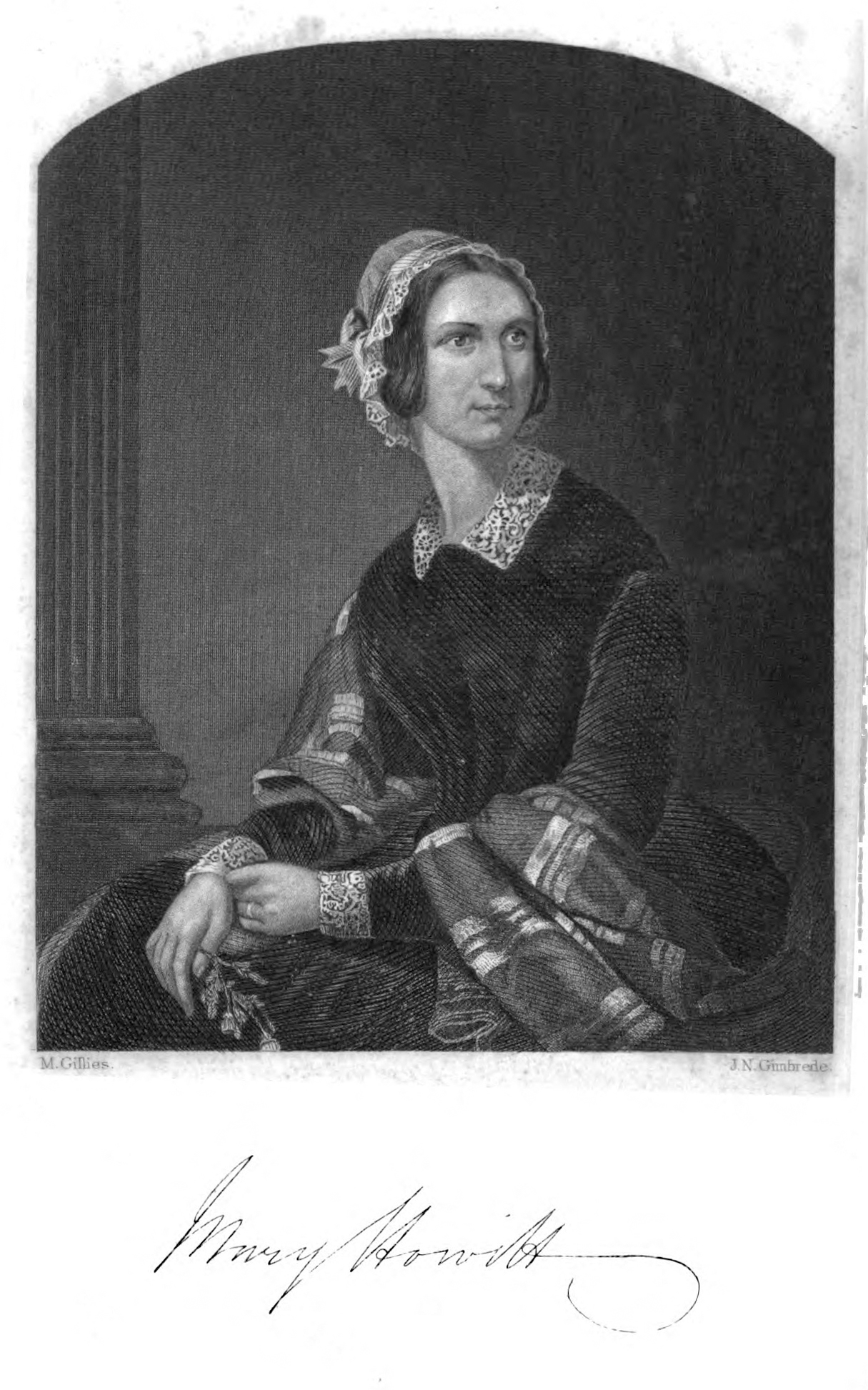

I’ve found another North Staffordshire book and author, My own Story, or the Autobiography of a Child (1845). The author Mary Howitt (1799-1888) was one of the top writers of the period. She grew up in Uttoxeter and the surrounding district. Her short book is very vivid and readable today, though sadly the chapter on “Town Customs” is short and notes only three of the Uttoxeter customs. One of these customs is, however, the town’s bull-baiting and a child’s view of it.

There is also her multi-volume Mary Howitt; an autobiography (1889) in which Chapter II is titled “Early Days at Uttoxeter”. After her marriage she and her equally literary-minded husband went to live in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, to take over a dispensing chemist shop of all things. This rather unlikely venture opens Chapter V, which also includes her eyewitness account of a lecture by the notorious Stoke preacher ‘Muley Moloch’ at his height. The couple lasted seven months in the quickly “despised” Hanley of 1821, before moving away and ending up in Nottingham (and then in the 1830s to Surrey, so as to be nearer the London publishers and magazines, then to London itself from 1843).

There is no survey-essay online, covering the whole of her vast output. But in the 1950s there was a joint biography Laurels & Rosemary: The Life of William and Mary Howitt (Oxford University Press, 1955), and a Kansas University Press volume Victorian Samplers: William and Mary Howitt (1952). Both are long out-of-print and not online. I have not seen them, but know that the title of the latter is misleading, as it is a biography rather than a sampler drawn from their output.

I made a brief search-based examination of the output. This unearthed a range of interesting local material. For instance, the early joint poem The Desolation of Eyam (1827), which describes a deadly 17th century outbreak of the plague in the Peak District. Later Mary wrote at least one fairy poem set in the Staffordshire Moorlands…

And where have you been, my Mary ?

And where have you been from me ?

I’ve been to the top of Cauldon Lowe,

The midsummer night to see.

This is from “The Fairies of the Cauldon Low”, found in the collection Ballads and Other Poems (1847). I see that the book also has other faerie poetry such as “Isles of the Sea Fairies”, “The Voyage with the Nautilus”. These seem lively and well done, but the bulk of her poetry is Victorian and unpalatable today. Her book collections of poetry can certainly appear off-putting, padded with too many cloying Victorian ‘religious sentiment poems’ of the sort paid for by Annuals, and generally displaying the ornate thee-and-thou style of the time. One can understand why Howitt wasn’t much remembered for her mainstream poetry in the 1890s-1900s, the decades after her death. Her conversion to Catholicism in old-age (1883), complete with a move of residence to Rome, probably didn’t help her reputation to survive.

She does appear to have had quite a taste for the macabre, despite her staunch religious beliefs. For instance she was the author of the classic macabre poem “The Spider and the Fly” (1828), for which she is still remembered today and which is still the subject of adaptation and illustration. Note also that Ballads and Other Poems has an interestingly macabre backwoods poem “The Tale of the Woods”. Possibly there are more such poems to be found in her output. There further appear to be interesting items of natural history such as “The Fossil Elephant” and the comic “True Story of Web-Spinner”. Possibly more are to be found in her book Songs of Animal Life (1843) and With the Birds (c. 1880s?). Her poems “Deliciae Maris” describes a lost temple in the arctic and its companion “Dolores Maris” a number of monsters under the sea.

She was also the first English translator of Hans Christian Andersen stories (Wonderful Stories for Children, 1846), apparently done on the basis of her having already translated at least one of his novels. The story collection was followed a year later by her translation of Andersen’s The True Story of My Life (1847), and Hans Andersen’s Story Book: With a Memoir (1853). Her first book of Andersen stories was done in a slightly toned-down form, acceptable to an English publisher and his purchasing public and reviewers. Only one of the stories in Wonderful Stories for Children is said to have actually had its plot slightly tweaked (so that storks did not deliver dead new-born babies to doorsteps). It appears that a certain continental Andersen scholar was later made apoplectic, on discovering ‘zis sacrilege by ze philistine Englisherz’, and in the 1950s he effectively destroyed her reputation as a translator by finding about 40 errors. Her translations may have been a little stiff compared to the originals, but how else could she have seen Andersen published and read by children in England and America during the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign? Howitt also translated many volumes of the work of Frederika Bremer, and also Icelandic sagas and Swedish folk-songs (see The Literature and Romance of Northern Europe, 1852).

Her attempt at publishing a paid journal-magazine Howitt’s journal of literature and popular progress lasted only two years, perhaps marred by an attempt to blend politics (pro Free Trade, anti the Death Penalty, apparently) with literary work and sketches. But even a cursory glance at it reveals an evident tendency to the macabre. For instance, Howitt’s journal published three tales which were later included in the modern Penguin Classics collection Gothic Tales. These were by Howitt’s friend “Cotton Mather Mills”, a pseudonym for Elizabeth Gaskell. Howitt had first met Gaskell on an 1841 tour of the Rhineland, where she is said to have aroused Elizabeth to an abiding interest in the macabre by telling her terrifying night-time stories — thus setting Gaskell on the path to writing such stories herself. Gaskell’s first gothic stories were published in Howitt’s journal. The journal also published Eliza Meteyard, another author who appears to have had a connection to the Staffordshire/Derbyshire Peak (see Dora and her Papa).

As if to confirm Howitt’s interest in the macabre, a few years later she and her husband — by now a veritable ‘writing-machine’ duo — also popped out a hefty two-volume translation from the German of The History of Magic (1851)…

Note that Mary has taken the opportunity to compile a new survey of true-life accounts of such things, which at that time must have taken quite some doing in terms of reading and research. She was in London at that time, so presumably had the British Library available for use. This interest paralleled… “the temporary immersion of both of them in the fashionable practice of mesmerism [hypnotism] and spiritualism of the eighteen fifties” (from a review of Laurels & Rosemary: The Life of William and Mary Howitt, 1955). Obviously her previously staunch Quaker beliefs didn’t preclude an interest in insidiously genteel cults like spiritualism. Later her husband published a two volume History of the Supernatural.

But, returning to her early years, I see that Staffordshire was the setting for her breakthrough adult book Wood Leighton: A Year in the Country (1836). Specifically, it is set in the once-vast Needwood Forest and the adjacent town of Uttoxeter. Her early poem “May Fair”, a vivid account of the May Fair day at Uttoxeter (“And these will go to see the Dwarf, and those the Giant yonder”) here gains a companion rendering in prose. As a child Mary had been familiar with the surviving parts of the ancient Forest. For instance her book Tales in Prose contains a section giving a number of more or less fantastical “Anecdotes” from her childhood — including one where she is in Needwood Forest…

“What a horror now fell upon us! The glade was like an enchanted forest: all at once the trees seemed to swell out to the most gigantic and appalling size ; every twisted root seemed a writhing snake, and every old wreathed branch a down-bending adder ready to devour us. The holly thickets seemed full of an increasing blackness, which, like a dreadful dream, appeared growing upon our imagination till it was too horrible to be borne. We felt as if hemmed in by a mighty wilderness of gloom that cut us off from our kindred…”

A North Staffordshire Field Club excursion report of 1896 suggests that her successful The steadfast Gabriel: a tale of Wichnor Wood (1848) was also set locally, but possibly the author was mis-remembering after a period of some 40 years. Because a 1965 survey book of Nineteenth Century Children: Heroes and Heroines claims her book was set in the Forest of Dean, noting that coal mining occurs within the forest. Yet the 1965 author was making a broad survey of thousands of books and thus might have been misled as to the setting. The steadfast Gabriel was a well-reviewed ‘woodland life’ book for children in middle-childhood and was said to be part of the “William and Robert Chambers’ series of ‘novels for the people'”. On the location, I would be inclined more to trust a member of the North Staffordshire Field Club. It is however difficult to confirm that Wichnor Wood does/doesn’t = Needwood Forest, because it’s not freely available online. Only Hathi has it, and even there it’s locked down. There’s almost no mention of it in her Autobiography, only a mention that it was written to order for the Chambers series. Perhaps it was effectively a children’s version/re-write of her earlier three-volume Wood Leighton?

Howitt’s Autobiography notes that her child-self delighted in places like Chartley… “It and its surroundings were all wonderfully weird and hoary”. Chartley was an enclosure of the ancient Needwood. She would later produce with her husband a sumptuously illustrated book of similarly “weird and hoary” places, the Ruined Abbeys and Castles of Great Britain (1862). A publisher appears to have heavily shaped this book, including the bizarre addition of the antiquated long-s throughout the text. Still, its presence in her output again suggests Mary’s interest in such gothic places and their lore.

Howitt did however write at least one remarkably vivid topographical / autobiographical article of local interest, beyond recalling her childhood in autobiography…

“… articles from Mrs Howitt’s pen appeared in the Eclectic Review, 1859, called “Sun Pictures”, a delightful account of a journey [three nights, on foot] through this country [into the high Moorlands], and giving a charming description of Alton, Ipstones, and the district. I remember the landlord of the Inn at Ipstones was very indignant at his portrayal, and breathed out threatenings and slaughter at the author of what everybody but himself thought a life-like picture.” (N. Staffs Field Club Trans., 1896)

I’ve extracted and compiled the “Sun Pictures” (1859) in PDF (100Mb), as it seems to have been totally forgotten. It’s well worth reading, and although it is certainly “charming” in a great many places, the charm is deliciously and seamlessly counterpointed by her obvious taste for the macabre — depicting things like encountering a creepy changeling boy on a railway platform, lovingly describing many grotesque and curious personalities, encountering gypsies carrying a strange mis-shapen woman in their sideshow caravan, and recounting a gruesome olde time murder in the wind-swept Moorlands. “Sun Pictures” has its share of dark among the light. It’s out of copyright and would make a fine graphic novel or even an Under Milk Wood style audio drama/reading.

Most of the real names in “Sun Pictures” are omitted or obfuscated under fictional names. She and her daughter appear to have first taken the train from Alton to Biddulph. The ornamental gardens and organ player are obviously at Biddulph Grange, though the place is not named. Then they took the train from Biddulph to Cheddleton or perhaps Leek; then walked up into the hills. After that presumably Waystones = Ipstones, Rams = Foxt; Foxholes = Swineholes; High Stone Edge = the Ipstone Edge; Wyver = Cauldon; then a walk across Wyver Lowe = Cauldon Lowe; across the unnamed Weaver Hills (“to the west … lie the great quarries”); Welstone = Ellastone; Sturton = Alton; they end the journey by entering The Dale = Rakes Dale adjacent to Alton Castle, and they arrive at their summer home base at what may have been the small village of Hansley Cross which is adjacent to Alton. Thornborough Hall may = Alton Towers or perhaps even the Castle, and terming it a “farm-house” may be some jest by the author or some allusion to a common local jest.

Further reading:

Quaker to Catholic: Mary Howitt, Lost Author of the 19th Century, 2010. By a local author, who lives in Uttoxeter.

“The ‘Airy Envelope of the Spirit’: Empirical Eschatology, Astral Bodies and the Spiritualism of the Howitt Circle”, Intellectual History Review, 2008.

Laurels & Rosemary: The Life of William and Mary Howitt, Oxford University Press, 1955.

Victorian Samplers: William and Mary Howitt, University of Kansas Press, 1952.

Her letters are at The University of Nottingham’s Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, having been purchased in the 1990s. They also hold an East Midlands Collection which has many examples of the Howitt books.

A suggested contents list for a new locally-oriented print-on-demand/ebook anthology of her work…

* A new introductory essay.

* Selections from My own Story, or the Autobiography of a Child (1845).

* Selections from Mary Howitt; an autobiography (1889): Chapter II “Early Days at Uttoxeter”, the Stoke-on-Trent part of Chapter V, and other local passages.

* “The Desolation of Eyam” (1827) – a deadly 17th century outbreak of the plague in the Peak District.

* “The Fairies of the Cauldon Low”.

* “May Fair” (long poem on the Uttoxeter May Fair).

* The relevant “Anecdotes” from Tales in Prose.

* Extracts from Wood Leighton: A Year in the Country (1836), set in Needwood Forest and Uttoxeter.

* Woodland scene extracts from The steadfast Gabriel, probably reflecting her early experience of Needwood Forest.

* Any local items from the run of her magazine Howitt’s journal of literature and popular progress.

* “The Spider and the Fly” (1828) and any other curious animal / monster poems.

* “Sun Pictures” (1859) with annotation.

* Extracts from her letters, re: North Staffordshire, Uttoxeter and Stoke.

And any other newly-discovered locally interesting material from her vast output.

Craig Horne here from Melbourne Australia. I recently wrote a biogrphy of Alfred Howitt the son of Mary and William Howitt. please see the link below and a copy of a recent review of the book. I’m interested in learning more about Mary and William (even though I have included extensive biogrAphical information in Line of Blood) with aview to a possible biography. I’d appreciate any assistance you can give.

https://melbournebooks.com.au/products/line-of-blood

The following review in The Saturday Paper this morning was written by Celeste Liddle an Arrernte woman living in Melbourne and is a union organiser, social commentator, freelance writer and activist.. The Arrernte People are from the area now known as Alice Springs and the East McDonalds and were displaced following the exploration of the region by John McDouall Stuart, Alfred Howitt and the fiasco that was the Burke and Wills expedition.

Here’s the review:

Line of Blood: The Truth of Alfred Howitt

“The advance of settlement which has, upon the frontier at least, been marked by a line of blood…” – Craig Horne, quoting Alfred Howitt.

One day, I searched online for “Arrernte skin names”. I was undertaking self-education – finding some pieces of further information in a family history that, while known, had also been fragmented by previous governmental policies. I found an octagonal line diagram that not only showed me why my father had one skin name and I another, but also laid out how I was related to various people in the Arrernte system and who I could marry. In short, via a simple line diagram, I got a clearer picture of cultural connectedness.

On reading Horne’s biographical exploration of his ancestor – anthropologist, explorer, scientist and public servant Alfred Howitt – I now understand what a fraught place this simple image of kinship came from. If Howitt hadn’t been attempting to siphon knowledge from Kurnai peoples in Victoria in order to validate his Darwinist and white supremacist understandings, perhaps Brabiralung knowledge man Tulaba would not have arranged a series of matchsticks in a similar way to that line diagram to demonstrate the complexity of local kinship. And perhaps we would not have similar diagrams made by Howitt’s contemporaries that highlight other kinship structures from clans across the country.

Line of Blood: The Truth of Alfred Howitt, constructed via archival documentation, family history, Howitt’s works and external accounts, is an informative and often harrowing read. We are introduced to a man who was born into a progressive and unconventional (for the time) literary family. He came to Australia to seek his fortune in the goldfields and then became the celebrated finder of the remains of Burke and Wills.

Though his fortunes fluctuated over the decades, Howitt’s documentation of Kurnai society and culture led to him achieving recognition. While Horne takes care to not diminish these achievements, he unpacks the character of a man who was an arch-conservative and who exploited Indigenous knowledges and peoples to service his own Eurocentric biases.

At times, I found myself recoiling from the page. Yet through his work, Horne reminds me that due to the processes of colonisation and the roles people like Alfred Howitt played in justifying these practices, often we – Aboriginal people – are left to reconstruct cultural knowledge documented by those who were deeply invested in our communities dying out.

Horne’s work is a timely example of the truth-telling that needs to occur in this country for us to reach maturity. Line of Blood is an apt title for a work that not only covers the bloodshed across this country but also the ancestral legacies we must confront.

Melbourne Books, 272pp, $34.95

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on August 26, 2023 as “Line of Blood: The Truth of Alfred Howitt”.

Many thanks, Craig. My expanded journal article is probably the best thing I can point you to, in the scholarly journal Penumbra #3… https://www.hippocampuspress.com/journals/penumbra/penumbra-no.-3-2022