A Chartist leader escapes from the Potteries, 1842. From The Life of Thomas Cooper:

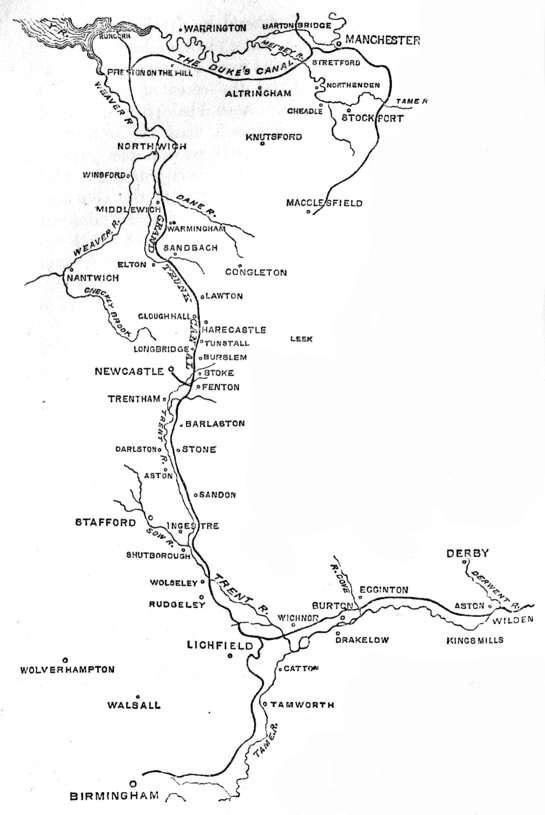

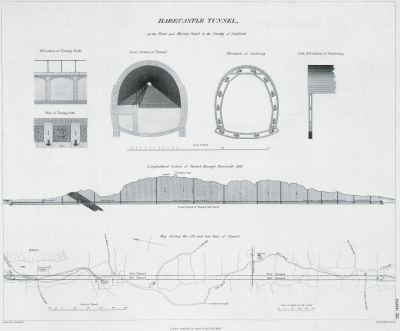

At dusk, I closed the [Chartist] meeting; but I saw the people did not disperse; and two pistols were fired off in the crowd. No policeman had I seen the whole day! And what had become of the soldiers I could not learn. I went back to my inn; but I began to apprehend that mischief had begun which it would not be easy to quell. […] two Chartist friends went out to hire a gig [horse carriage] to enable me to get to the Whitmore station, that I might get to Manchester: there was no railway through the Potteries, at that time. But they tried in several places, and all in vain. No one would lend a gig, for it was reported that soldiers and policemen and special constables had formed a kind of cordon round the Potteries, and were stopping up every outlet.

Midnight came, and then it was proposed that I should walk to Macclesfield, and take the coach there at seven the next morning, for Manchester. Two young men, Green and Moore, kindly agreed to accompany me; and I promised them half-a-crown each.

[He disguises himself] Miss Hall, the daughter of Mr. Hall the land-lord of the George and Dragon, lent me a hat and great-coat I put them on, and putting my travelling cap into my bag, gave the bag to one of the young men, and my cloak to the other; and, accompanied by Bevington and other friends, we started. They took me through dark streets to Upper Hanley; and then Bevington and the rest bade us farewell, and the two young men and I went on.

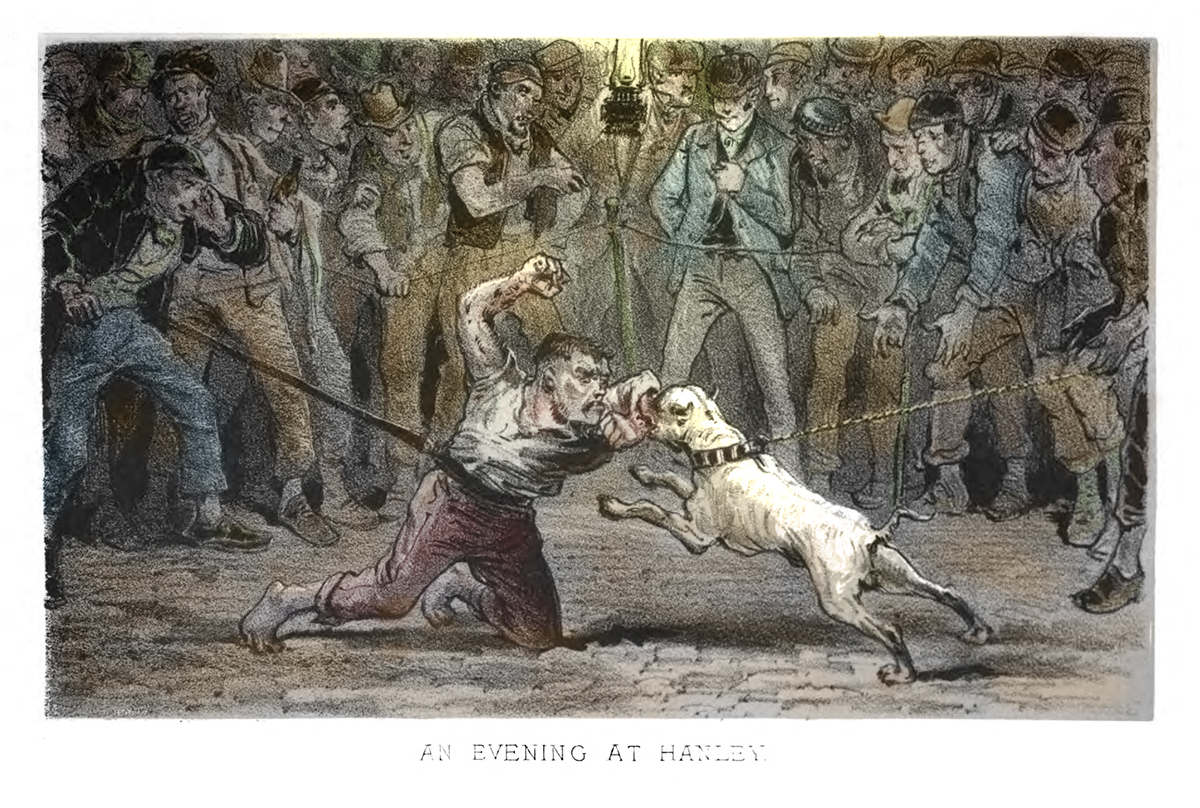

My friends had purposely conducted me through dark streets, and led me out of Hanley in such a way that I saw neither spark, smoke, or flame. [of the riot, and] during that night scenes were being enacted in Hanley, the possibility of which had never entered my mind, when I so earnestly urged those excited thousands to work no more till the People’s Charter became the law of the land. Now thirty years have gone over my head, I see how rash and uncalculating my conduct was. But, as I have already said, the demagogue is ever the instrument rather than the leader of the mob.

[Instruction was given to] the two young men, Green and Moore, who accompanied me, not to go through Burslem, because the special constables were reported to be in the streets, keeping watch during the night; but to go through the village of Chell, and avoid Burslem altogether.

I think we must have proceeded about a mile in our night journey when we came to a point where there were two roads; and Moore took the road to the right while Green took that to the left.

[… they argue tediously for some minutes …]

” I tell thee that I’m right,” said the one.

” I tell thee thou art wrong,” said the other.

And so the altercation went on, and they grew so angry with each other that I thought they would fight about it.

” This is an awkward fix for me,” said I, at length. “You both say you have been scores of times to Chell, and yet you cannot agree about the way. You know we have no time to lose. I cannot stand here listening to your quarrel. I must be moving some way. You cannot decide for me. So I shall decide for myself. I go this way,” — and off I dashed along the road to the left, Moore still protesting it led to Burslem, and Green contending as stoutly that it led to Chell.

They both followed me, however, and both soon recognised the entrance of the town of Burslem, and wished to go back.

” Nay,” said I, “we will not go back. You seem to know the other way so imperfectly, that, if we attempt to find it, we shall very likely get lost altogether. I suppose this is the highroad to Macclesfield, and perhaps it is only a tale about the specials [volunteer night-guards at Burslem].’

In the course of a few minutes we proved that it was no tale. We entered the market-place of Burslem, and there, in full array, with the lamp-lights shining upon them, were the Special Constables! The two young men were struck with alarm; and, without speaking a word, began to stride on, at a great pace. I called to them, in a strong whisper, not to walk fast — for I knew that would draw observation upon us. But neither of them heeded. Two persons, who seemed to be officers over the specials, now came to us. Their names, I afterwards learned, were Wood and Alcock, and they were leading manufacturers in Burslem.

” Where are you going to, sir? ” said Mr. Wood to me. “Why are you travelling at this time of the night, or morning rather. And why are those two men gone on so fast?”

“I am on the way to Macclesfield, to take the early coach for Manchester,” said I; “and those two young men have agreed to walk with me.”

” And where have you come from?” Asked Mr. Wood; and I answered, “From Hanley.”

“But why could you not remain there till the morning ?”

“I wanted to get away because there are fires and disorder in the town — at least, I was told so, for I have seen nothing of it.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Alcock had stopped the two young men.

“Who is this man?” He demanded; “and how happen you to be with him, and where is he going to?

“We don’t know who he is,” answered the young men, being unwilling to bring me into danger” he has given us half-a-crown a piece, to go with him to Macclesfield. He’s going to take the coach there for Manchester, to-morrow morning.”

” Come, come,” said Mr. Alcock, “you must tell us who he is. I am sure you know.”

The young men doggedly protested that they did not know.

“I think,” said Mr. Wood, “the gentleman had better come with us into the Legs of Man” (the principal inn, which has the arms of the Isle of Man for its sign), “and let us have some talk with him.”

So we went into the inn, and we were soon joined by a tart-looking consequential man.

“What are you, sir?” Asked this ill-tempered-looking person.

“A commercial traveller,” said I, resolving not to tell a lie, but feeling that I was not bound to tell the whole truth. And then the same person put other silly questions to me, until he alighted on the right one, ” What is your name ?”

I had no sooner told it, than I saw Mr. Alcock write something on a bit of paper, and hand it to Mr. Wood. As it passed the candle I saw what he had written, — “He is a Chartist lecturer.”

“Yes, gentlemen,” I said, instantly, “I am a Chartist lecturer; and now I will answer any question you may put to me.”

“That is very candid on your part. Mr. Cooper,” said Mr. Alcock.

” But why did you tell a lie, and say you were a commercial traveller?” – asked the tart-looking man.

“I have not told a lie,” said I; “for I am a commercial traveller, and I have been collecting accounts and taking orders for stationery that I sell, and a periodical that I publish, in Leicester.”

“Well, sir,” said Mr. Wood, “now we know who you are, we must take you before a magistrate. We shall have to rouse him from bed; but it must be done.”

Mr. Parker was a Hanley magistrate, but had taken alarm when the mob began to surround his house, before they set it on fire, and had escaped to Burslem. He had not been more than an hour in bed, when they roused him with the not very agreeable information that he must immediately examine a suspicious-seeming Chartist, who had been stopped in the street. I was led into his bedroom, as he sat in bed, with his night-cap on. He looked so terrified at the sight of me — and bade me stand farther off, and nearer the door! In spite of my dangerous circumstances I was near bursting into laughter. He put the most stupid questions to me; and at his request I turned out the contents of my carpet-bag, which I had taken from the young men, with the thought that I might be separated from them. But he could make nothing of the contents – either of my night-cap and stockings, or the letters and papers it held.

Mr. Wood at last said, “Well, Mr. Parker, you seem to make nothing out in your examination of Mr. Cooper. You have no witnesses, and no charges against him. He has told us frankly that he has been speaking in Hanley; but we have no proof that he has broken the peace. I think you had better discharge him, and let him go on his journey.”

Mr. Parker thought the same, and discharged me. His house was being burnt at Hanley while I was in his bedroom at Burslem. I was afterwards charged with sharing the vile act. But I could have put Mr. Parker himself into the witness-box to prove that I was three miles from the scene of riot, if the witnesses against me had not proved it themselves. The young men, by the wondrous Providence which watched over me, were prevented going by way of Chell. If we had not gone to Burslem, false witnesses might have procured me transportation for life [to Australia as a convict].

Were these young men true to me? Had they deserted me, and gone back to Hanley ? No: they were true to me, and were waiting in the street; and now cheerily took the bag and cloak, and we sped on again, faster. We had been detained so long, however, that by the time we reached the “Red Bull,” a well-known inn on the highroad between Burslem and the more northern towns of Macclesfield, Leek, and Congleton, one of the young men, observed by his watch that it was now too late for us to be able to reach Macclesfield in time for the early coach. The other young man agreed; and they both advised that we should strike down the road, at the next turning off to the left, and get to Crewe — where I could take the railway for Manchester. We did so; and had time for breakfast at Crewe, before the Manchester train came up, when the young men returned [to the Potteries].

A second special Providence was thus displayed in my behalf. If we had proceeded in the direction of Macclesfield, in the course of some quarter of an hour we should have met a crowd of working men, armed with sticks, coming from Leek and Congleton to join the riot in the Potteries. That I should have gone back with them, I feel certain; and then I might have been shot in the street, as the leader of the outbreak.